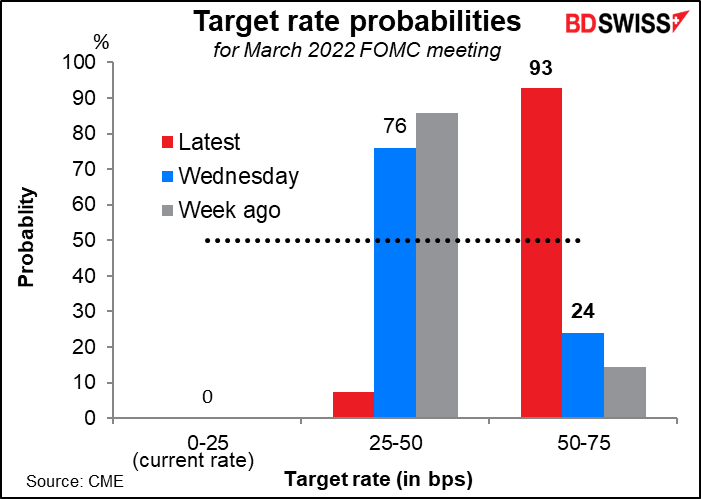

Thursday’s higher-than-expected US consumer price index (CPI) was the last straw for the markets. With inflation now at 7.5% yoy, the highest since 1982, investors upped their estimates for US rates. A 50-bps hike in March went from being an outside possibility (24% probability) to a near-certainty (93% probability) while a 25 bps hike went from being the market consensus (76%) to having almost zero probability.

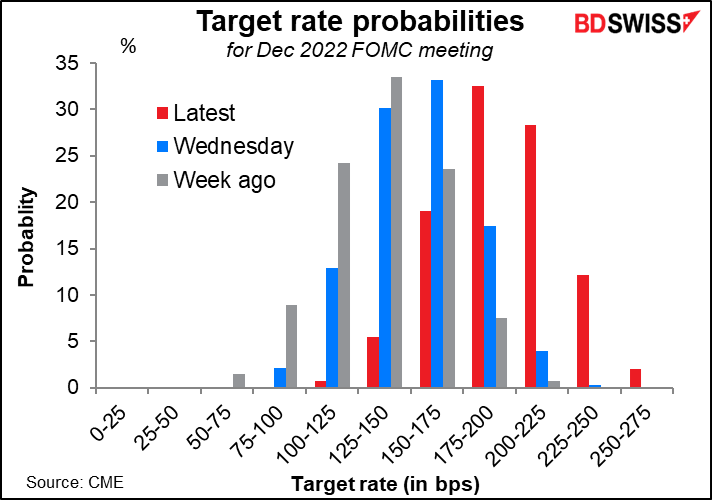

The market now sees the Fed tightening policy by 175 bps – 200 bps this year. That’s 50 bps more than it saw a week ago.

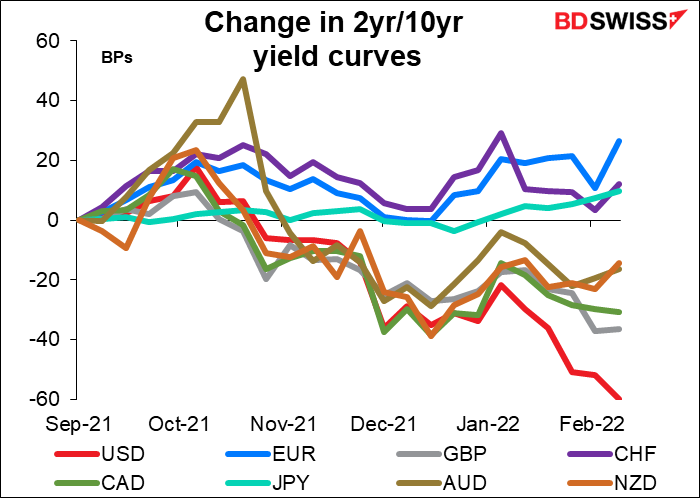

Is there a chance that the Fed – and other central banks – tighten too far? Yield curves have been flattening across the globe, a sign that investors think a) higher short-term rates are coming and b) lower inflation is likely over the longer term.

You can see it better if we look at the change in yield curves over the last several months, The US yield curve in particular has flattened a lot.

Markets expect this trend to continue in most countries. If we look at the market expectations for yield curves two years from now, the US yield curve is expected to be inverted, as are Britain and Australia (barely). The EU is expected to be almost flat, as are New Zealand and Canada.

Only the perennial outlier, Japan, is expected to be steeper than today, probably because investors expect the Bank of Japan to loosen its yield curve control policy. The BoJ however reaffirmed that policy Thursday as they offered to buy an unlimited amount of 10-year bonds at their upper limit to 0.25%. This move is in sharp contrast to other central banks, which are debating when and how to start shrinking their balance sheets. It reinforces my belief that JPY is likely to weaken substantially unless inflation starts to take off in Japan (which is a distinct possibility for the first time in many years).

An inverted yield curve is often associated with a recession. Not that they cause recessions but that’s the usual response of fixed income professionals when they think short-term interest rates are going to be high enough to cause a recession.

As a result while most countries saw an increase in rate expectations over the next year or two, New Zealand saw a decline in expectations for rates over the next two years – meaning people think the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is likely to over-tighten and will have to loosen policy next year.

The UK saw a decline in both one- and two-year rate expectations as UK Chief Economics Pill tried to calm market fears of higher rates. He predicted that raising rates as sharply as market pricing implied — to 1.2% by year-end — would push inflation below the Bank’s 2% target, which he implied the Bank wouldn’t like to see.

Several ECB officials also tried to push back against the market, but their impact was offset by discord on the Governing Council. ECB President Lagarde said in testimony to the European Parliament that “any adjustment to our policy will be gradual,” while Bank of France Gov. Villeroy de Galhau said the market had overreacted to the ECB press conference in pushing up rate expectations. But the hard-liners on the Governing Council have a different view: the new head of the Bundesbank, Joachim Nagel, said the ECB might need to raise rates this year if inflation doesn’t slow, echoing comments by Austrian Central Bank Gov. Knot, who predicted a hike could come as early as October.

Notably Lagarde and Villeroy’s efforts weren’t successful; rate expectations for the next two years increased substantially.

The question I would like to raise here is: are flattening yield curves a warning sign for central bankers? Will we start to hear more comments like those from Pill and Lagarde pushing back against market pricing? Will the market go from thinking that central banks are behind the curve and will have to tighten faster than they’ve said (Australia being the main example there) to thinking that perhaps they’re not likely to tighten as fast as is already priced in (UK).

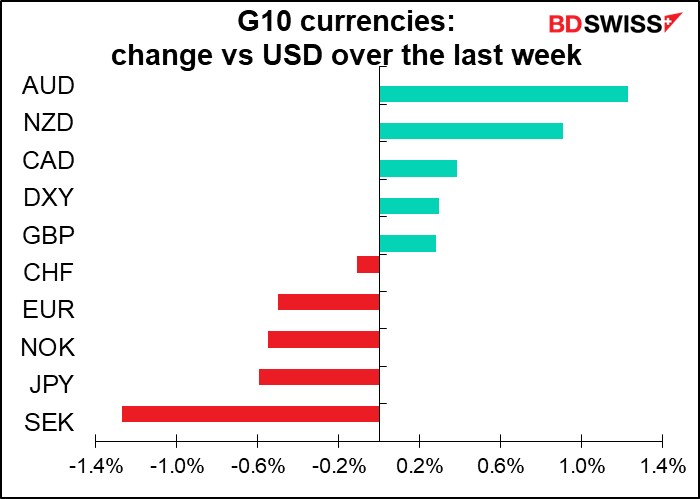

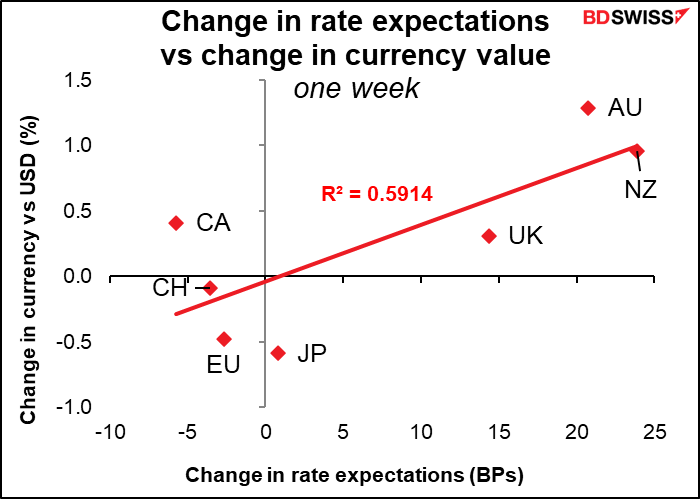

This is important because changes in rate expectations have been a major factor in driving currency performance recently, accounting for some 59% of the variation in currency performance over the last week. We should pay attention to any signs of central bankers trying to talk the markets down over the next week as more inflation figures come out.

Next week: more inflation shocks?

Next week we get consumer price inflation figures from Britain, China, Japan, and Canada. The US reports producer prices.

Britain’s headline inflation rate is expected to be unchanged at 5.4%. I’d be surprised. And even if it is stable, that doesn’t mean inflation in the UK has peaked. The Bank of England has already forecast that inflation will peak at around 7 1/4% around April. Perhaps that’s because of the heat & electricity bills in April that everyone is bracing for. The annual household energy bill is expected to rise by 54%. So everyone is just waiting for that bombshell.

As for Japan, it’s expected to remain the global outlier in inflation. The inflation rate is expected to slow to +0.6% yoy from +0.8% yoy as the Go To Travel campaign, which subsidized travel expenses, falls out of the comparison. Eventually the impact of this government-induced distortion and the cut in mobile phone charges should dissipate and leave Japan with inflation closer to the global norm, but not yet.

(No forecast is available yet for Canada’s CPI.)

China on the other hand is expected to see a decline in both its CPI and, more importantly, its producer price index (PPI). That’s important because China’s producer prices are in effect the rest of the world’s import prices for finished goods. Does this mean we may be getting past peak inflation? Possibly, it could be an early sign.

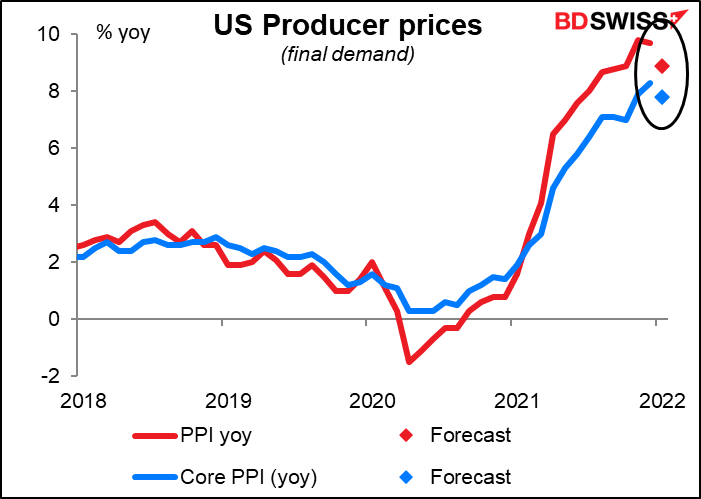

The US PPI is also expected to decline, albeit only slightly.

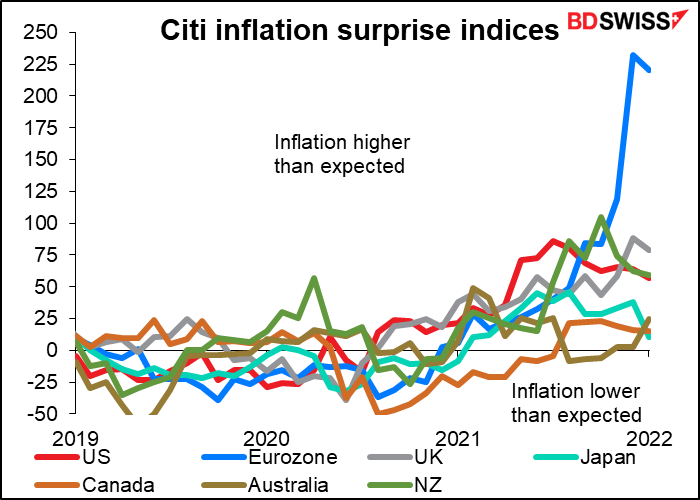

How much can we trust the inflation forecasts though? The US CPI came in above the market consensus forecast eight times over the last year and hit the forecast four times. It hasn’t come in below forecast since January 2021.

That’s a common phenomenon around the world, according to the Citi economic surprise indices for inflation. They show most countries missing inflation forecasts on the upside. (The indices haven’t been updated with Thursday’s US CPI yet.) Perhaps we can expect more upside surprises this coming week too with the result that those currencies appreciate.

Usually the star of the week would be the minutes of the latest meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which met on Jan. 26th. Analysts pour over the text trying to divine any differences or shades of opinion in an effort to divine where the Committee is headed. In this case, the main things they would be looking for are a) when will “lift-off” take place; b) how quickly will they raise rates; c) how soon after “lift-off” will they start shrinking the balance sheet; and d) how rapidly will they allow the balance sheet to shrink? Also some particularly keen people will be curious about how quickly they will run down their stock of Treasuries vs mortgage-backed securities.

However, I think the situation has changed so quickly that even the January minutes will now be seen as outdated. Since the meeting took place we got the blow-out January employment data showing hundreds of thousands more jobs than what they thought then plus Thursday’s inflation figure showing inflation much higher than they thought it was. Market participants are now looking ahead to the March meeting more than looking back at the January meeting.

There are also several retail sales figures coming out during the week: the US on Wednesday, UK and Canada on Friday. US retail sales are expected to be particularly buoyant, up 1.8% mom. This compares to the six-month moving average of barely any growth at all (+0.1%).

Much of this is because of a 7.8% surge in auto sales during the month. But even excluding autos, retail sales are expected to be up by 1.0% mom, whereas that series has shown no growth at all on average over the last six months. Signs of a rebound in consumption could boost sentiment for the dollar.

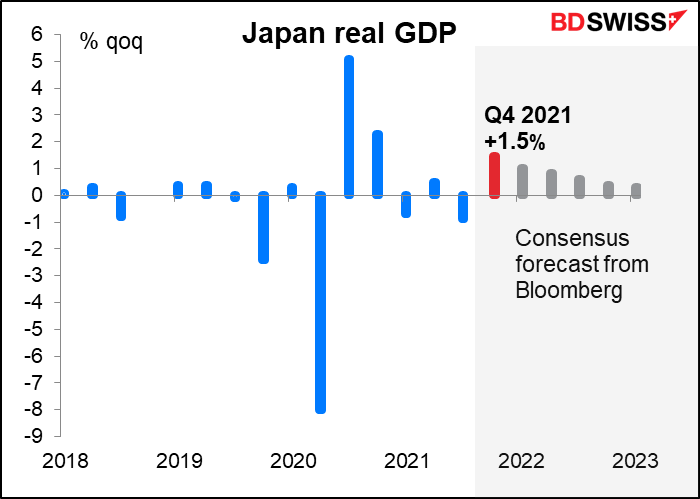

Japan releases its Q4 GDP data on Tuesday. The market expects a healthy rebound after the pandemic-induced decline in Q3. Services consumption improved markedly, as shown by improvement in the mobility data once the state of emergency declaration was lifted. Also auto exports picked up in November, which should allow net exports to make a contribution to growth.

However the collapse in the Eco Watcher’s Survey for January, with the current conditions index falling the most since March 2011, suggests that things haven’t been so great since then as higher food & energy prices and the re-imposition of some emergency measures in January weighed on activity. The Cabinet Office downgraded its assessment of current conditions, commenting that “Recovery in economic conditions seems weak because of impact by COVID-19 infections. Despite expectations of future rebound, concerns remain about rising costs and also infection trends in Japan and elsewhere.”

That outlook is reflected in forecasts for future quarters, which show growth tailing off over the rest of the year and into 2023. Japan is expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels of output in Q1 this year however.

The big question is whether this sluggish growth will prevent Japan’s inflation rate from rising even as global inflation surges? That seems to be what the forecasts for Bank of Japan rates indicate. If that’s so, then the yen is likely to weaken further as other countries normalize policy.

The EU also releases its Q4 GDP figure on Tuesday.

Other indicators out during the week include: