Oh, to be back in Japan now. Next week is Golden Week in Japan. That means there are three consecutive holidays:

- Tuesday: Constitutional Memorial Day

- Wednesday: Greenery Day (like St. Patrick’s Day, when everyone wears green? More like Arbor Day.)

- Thursday: Children’s Day (traditionally 3/3 was Girl’s Day and 5/5 was Boy’s Day, now they’re one public holiday).

That means most Japanese will simply take the whole week off, which is what the Japanese government intends. Japan has the most public holidays of any country (19) because the culture frowns on workers taking personal days off and so the government compensates. (Ask Glen Wood about this.) In olden days only New Year’s Day was a holiday – one day a year.

Alas the rest of us will still be beavering away. It’s a pretty intense week, with

- Three major central bank meetings: The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Monday, the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on Wednesday, and the Bank of England on Thursday

- UK local elections on Thursday

- The ever-popular US nonfarm payrolls on Friday, heralded by the ADP report on Wednesday

- The final manufacturing PMIs on Monday and service-sector PMIs on Wednesday (with some adjustment for the UK, which is on holiday on Monday). Also the US Institute of Supply Management (ISM) version of those reports.

- German unemployment (Tue), factory orders (Thu), and industrial production (Fri)

- New Zealand and Canadian employment data (Wed & Fri, respectively)

- Tokyo CPI (Fri)

- The regular monthly OPEC+ meeting (Fri)

The central bank meetings will no doubt be the focus of attention. This past week only one major central bank that I follow closely, the Bank of Japan, met. They’re a total outlier so their decision is no guide to what other central banks might do. Contrary to the trend almost everywhere else, they decided to double down on their “yield curve control” (YCC) program to make sure that interest rates don’t rise.

By contrast, every other central bank seems to be channeling Sylvester Stone: I want to take you higher. The only question is, as Tosca said, how much higher?

Sweden’s Riksbank, which I don’t follow closely, did meet this past week as well. They joined the global rate-hike bandwagon, finally raising their policy rate to 0.25% from zero and promising another two or three hikes this year.

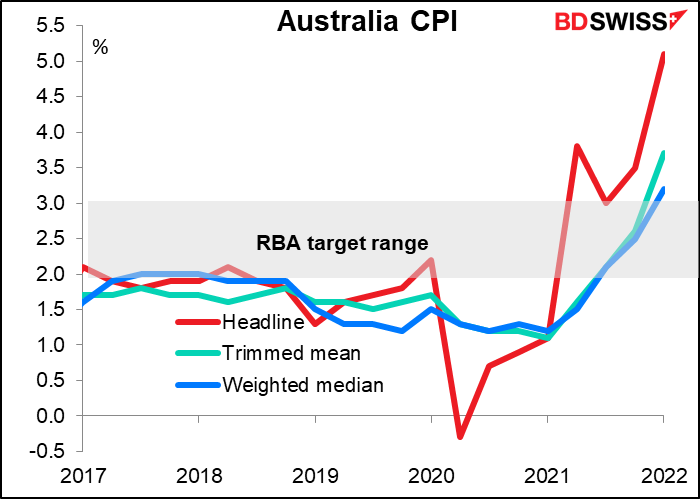

For next week the main question will be whether the RBA follows the Riksbank and joins the global hiking trend or whether it sticks with its view that Australia’s inflation is not “sustainably” within its 2-3% target range.

Until now it’s said that it wants to see “actual evidence” that inflation is “sustainably” within its 2%-3% target range before hiking. “Over coming months, important additional evidence will be available to the Board on both inflation and the evolution of labour costs,” it said last month, while noting that it will have “an updated set of forecasts to be published in May.” Under normal circumstances one might infer that those updated forecasts would be the trigger for a rate hike.

I don’t think they’ll need to wait for those forecasts. The surge in inflation in Q1 to 5.1% yoy from 3.5% reported this week was outside the range of all forecasts (4.0% to 4.9%, median 4.6%) and the highest in 21 years (since Q2 2001). The quarter-on-quarter rate of increase (2.1% qoq) met their target for the year-on-year rate! And both their core measures are now above the target zone.

This was followed by a surge in the producer price index (PPI) to 4.9% yoy from 3.7% yoy, the highest since Q4 2008, as reported this morning.

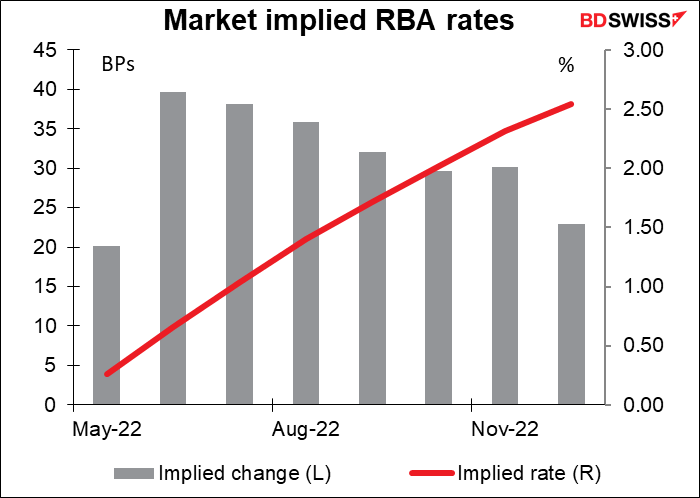

Accordingly, the market thinks – and I agree – that they will hike rates 15 bps to 0.25%. The expectation then is that once the RBA gets its new forecasts in May it might have to start playing “catch-up” and hike by 50 bps at a time.

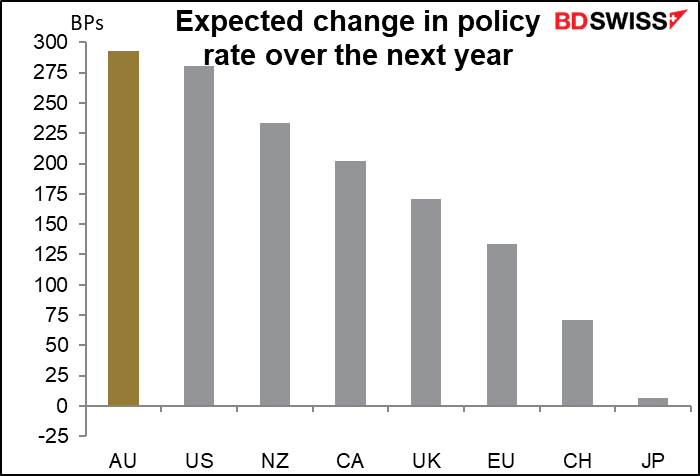

To make up for its slow start, the RBA is expected to tighten policy by the most of any of the major central banks over the next year. That’s a tall order. Will the RBA validate these expectations? That’s what Tuesday’s meeting will have to decide. I think it may take until May, when they have the new forecasts, before they fully change their tune. I think AUD could stumble after next week’s meeting if the RBA fails to confirm the market’s expectations.

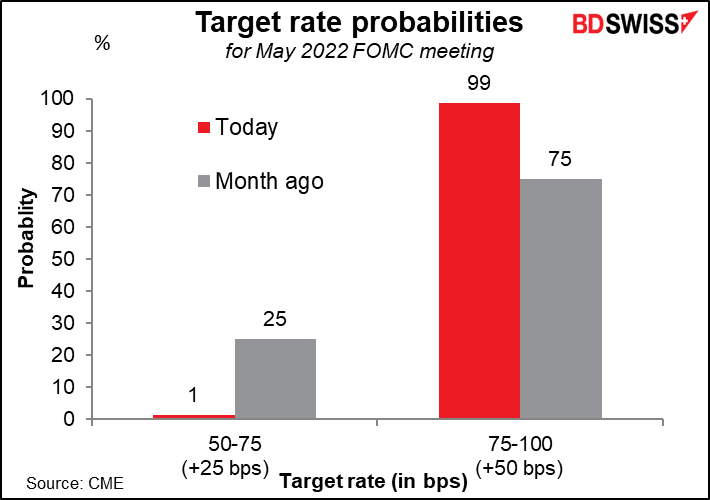

The Fed, by contrast, is pretty much a done deal. Last week (April 21st) Fed Chair Powell said that a 50 bps hike was “on the table” for the May meeting. Other Committee members have since chimed in with their support. The market now assumes it’s not only on the table but wrapped up and ready to go.

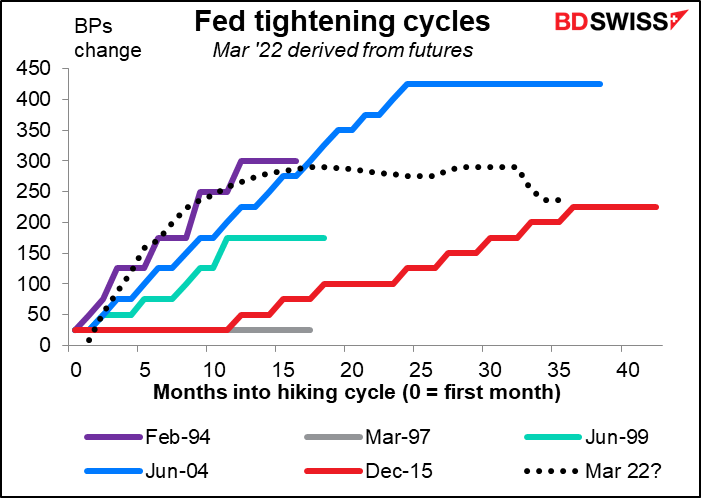

Powell also said “it is appropriate” in his view to “move a little more quickly” on interest rates than the Fed did during the 2004-2006 cycle, when the Fed hiked by 25 bps at every other meeting or even less frequently. The market is already pricing that it – it assumes as rapid an increase in rates as in 1994. Will the Fed validate that forecast? I expect so, as much as they can. They have said that each meeting will be “live,” that is, they will decide what to do at each meeting rather than going on a preset course, They therefore cannot pre-commit to tightening at a specific pace. But they may make it clear that they feel rates have to move “expeditiously,” as Chair Powell said, to neutral (estimated to be 2.4%) and perhaps higher to restrain inflation. That would validate the market’s pricing.

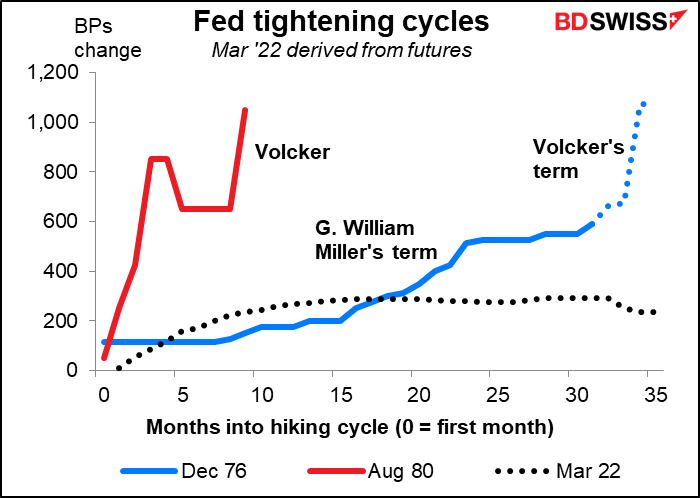

Of course with all the recent references to Paul Volcker (Fed Chair Aug. 1979-Aug 1987), some people are concerned that the Fed may be forced to follow the Dec 1976-Mar 1980 or, heaven forbid, the Aug 1980-May 81 tightening cycle, which saw rates move from an already high 9.5% to a record high 20% in just 10 months. That would be…I think “disastrous” is too mild a word. “Cataclysmic” would be more appropriate.

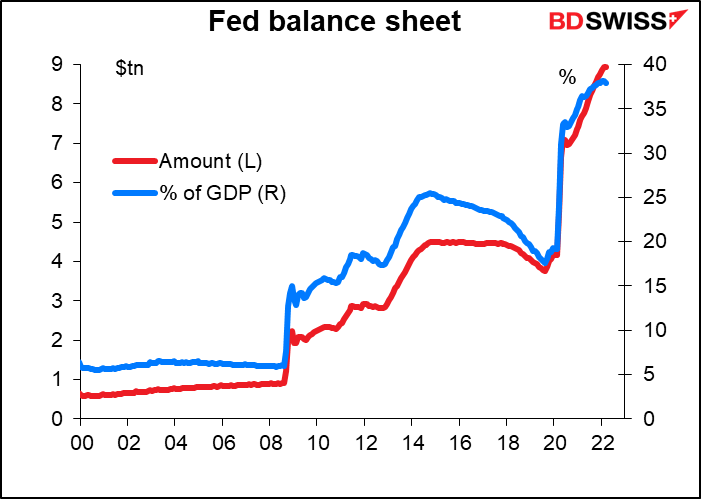

The other focus at the meeting will be when they will start their “quantitative tightening” (QT) or shrinking their swollen balance sheet by allowing bonds that they hold to mature without being rolled over. At their last meeting, in March, the Committee said that although no decision had been taken, the Fed was “well placed to begin the process of reducing the size of the balance sheet as early as after the conclusion of its upcoming meeting in May.” Given the further rise in inflation since then, we can expect them to announce the beginning of QT and more specifics about the pace.

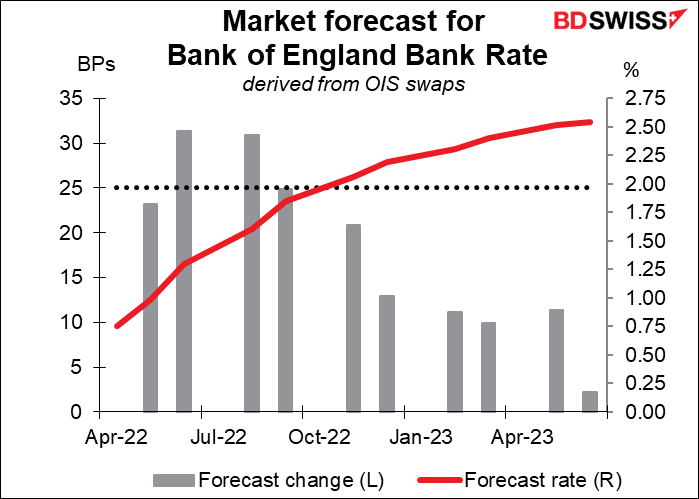

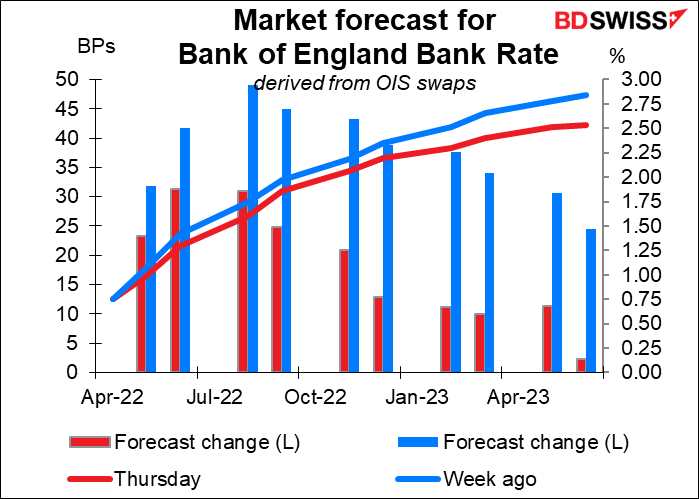

Then there’s the Bank of England. The market is pricing in a 25 bps hike at this meeting and a chance – but not a probability – of a 50 bps hike at the next meetings in June and August.

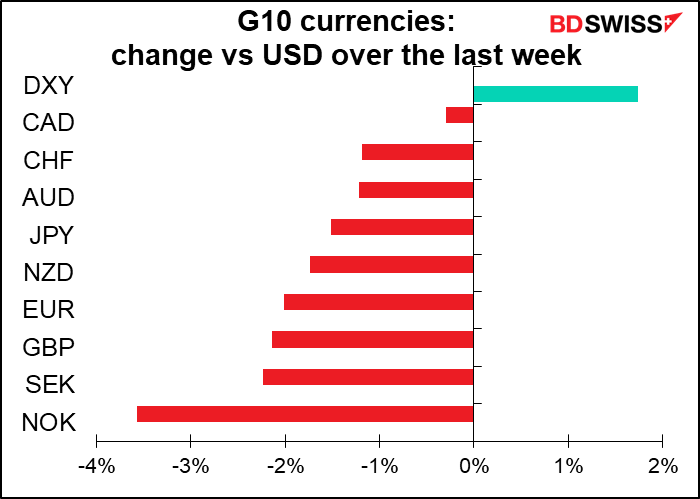

There’s been a major downgrade of rate expectations over the last week. The market had been pricing several 50 bps hikes but no more. Overall almost 50 bps of tightening over the coming year has been priced out. Rate expectations peaked on the 21st but then started to decline after the disappointing retail sales figures for March released the 22nd, which showed a 1.4% mom decline in retail sales.

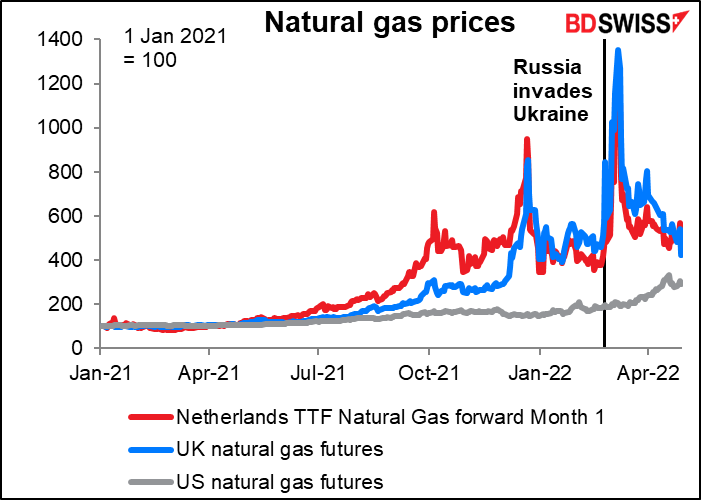

Bank of England Gov. Bailey last week emphasized that Britain’s situation was more like Europe’s than the US because Britain relies far more on natural gas to generate electricity. Natural gas prices have soared in the UK as well as on the continent, although they’ve come down substantially from their peak.

Speaking in Washington on the day rate expectations peaked, Bailey said the Bank is “walking a very tight line.” They have to raise rates to tackle inflation, but that will of course cause costs to rise for those households that have variable-rate mortgages (estimated at about one-quarter of all homeowners). Furthermore with tax hikes, energy price increases, and inflation surpassing wage increases, households are forecast to see the sharpest drop in living standards since records began in 1956. The Bank is therefore worried that pushing too hard against inflation could cause a recession.

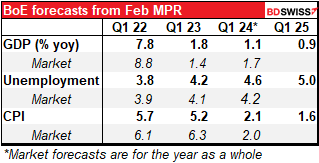

The meeting will also bring a new Monetary Policy Review with an update of the Bank’s forecasts. If we look at how the Bank’s forecasts compare to the market’s, the Bank may have to downgrade its growth outlook for next year somewhat while increasing its estimate of inflation. They might even forecast a recession at some point. That would tighten the already-tight line that the Bank is walking.

Last time, the Bank voted 8-1 to hike by 25 bps, with one member preferring to keep rates unchanged. Given the rise in inflation since then – at the time of the March meeting, the CPI was +5.5% yoy, now it’s +7.0% yoy – I don’t expect any votes to keep rates unchanged. However I do expect the Bank to emphasize the risks to growth. The MPC’s forward guidance currently reads, “the Committee judges that some further modest tightening in monetary policy may be appropriate in the coming months, but there are risks on both sides of that judgement depending on how medium-term prospects for inflation evolve.” Watch what they say about the risks – that will be key, I think.

If however Jon Cunliffe again votes for no change, and in particular if any of his colleagues join him, then I would expect to see investors revise down their forecasts for rates even more and for the pound to weaken further.

On the other hand, if there is a contingent agitating again for 50 bps hikes, as happened in February, then investors would think that they’ve underestimated the Bank’s resolve. Rate expectations would go shooting up and the pound would be likely to strengthen as a result. I think this is highly unlikely though. Catherine Mann, one of those who sought a 50 bps hike in February, recently made a speech in which she explained why she didn’t vote for a 50 bps hike in March. She explained that much comes down to household purchasing power, which as we’ve seen from the wages and retail sales data is deteriorating and likely to deteriorate further. Thus I see the Bank taking a more measures approach to tightening than those members wanted in February.

UK local elections

Some 200 local authorities across Britain are holding elections for around 7,000 seats on Thursday. Every council seat in Scotland, Wales and London is up for grabs and there are polls across much of the rest of England. The election will be a test for UK PM Boorish Johnson, who recently became the first PM ever to be fined for breaking the law while in office. If voters take out their anger at him by voting for an opposition party it could make life difficult for him. A poor performance in local elections can presage the ousting of an unpopular prime minister. PM Boorish Johnson’s predecessor, Theresa May, lost some 1,330 seats in May 2019 and a month later announced she would step down. Recent polls show Labour with a slight lead.

I doubt if PM Johnson will step down any more than Trump did after being impeached. He doesn’t seem like the kind of person who is embarrassed by his own behavior, and I doubt whether the other Tory party members of parliament want to go through all that right now. There’s no obvious front-runner within the party so it would not necessarily improve their chances.

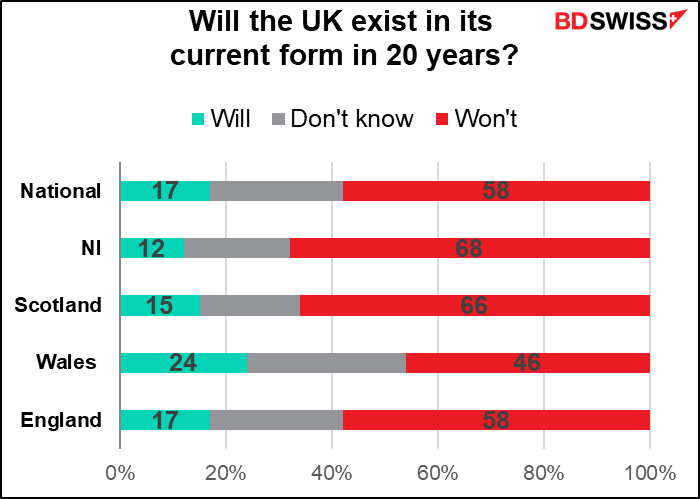

The most important part of the election, in my view, will the vote for the Northern Ireland devolved assembly. While the Scottish independence movement has captured most of the attention, it seems to me that Northern Ireland is more likely to break away from the United Kingdom first, not Scotland. A poll taken last year showed that 68% of the people in Northern Ireland didn’t think the UK would exist in its current form in 20 years, slightly higher than the 66% in Scotland.

Sinn Féin, a party that seeks to unify Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland in the south, is forecast to replace the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) as the largest party in the Assembly and claim the office of first minister. The DUP, as its name suggests, is committed to remaining within the United Kingdom, whereas Sinn Féin, which is also active in the Republic, has long been committed to unification with the South. (The party was historically associated with the Provisional Irish Republican Army, or IRA.) Sinn Féin has been trying to avoid that divisive question in this election and run on a more quotidian platform of health service, education, and dealing with the cost-of-living crisis. Nonetheless a victory for the party could elevate the question of UK dissolution somewhat, particularly as tensions rise between the UK and the EU over the province. (Note that Sinn Féin has never won the PM (taoiseach) office in the Republic.)

All in all, Thursday’s elections present an opportunity for GBP to fall even further.

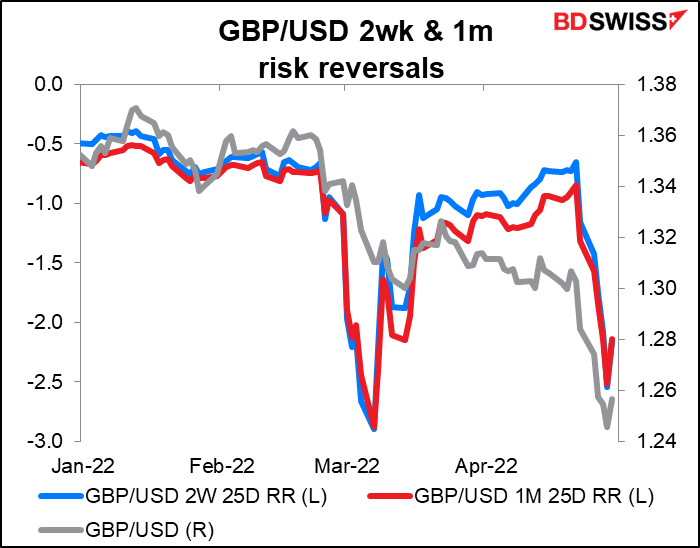

The elections don’t seem to have been affecting sterling so far. The one-month risk reversal (RR) didn’t fall a month before the elections, nor did the two-week RR fall two weeks ago. Rather they seem to moving together in line with the spot market.

Indicators: NFP

If that were all there is on the schedule, it would be enough. But it’s not.

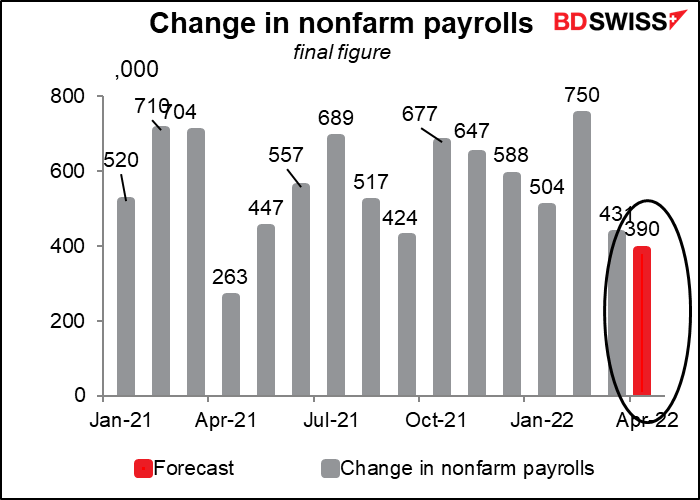

On Friday we get the US nonfarm payrolls. The market is expecting yet another healthy increase of 390, which would be down slightly from the previous month but still substantial.

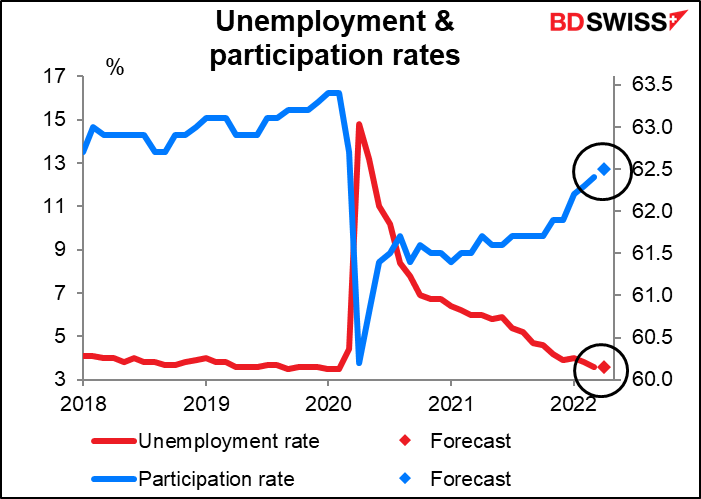

The unemployment rate is expected to stay at the previous month’s 3.6%, just a touch above the 50-year low of 3.5% achieved before the pandemic, while the participation rate is expected to edge up one tic. This will only confirm Fed Chair Powell’s contention that the job market is “extremely, historically tight” and “volatilely hot,” meaning that they can hike rates without fear of causing unemployment to soar to 10.8%, as it did under Volcker.

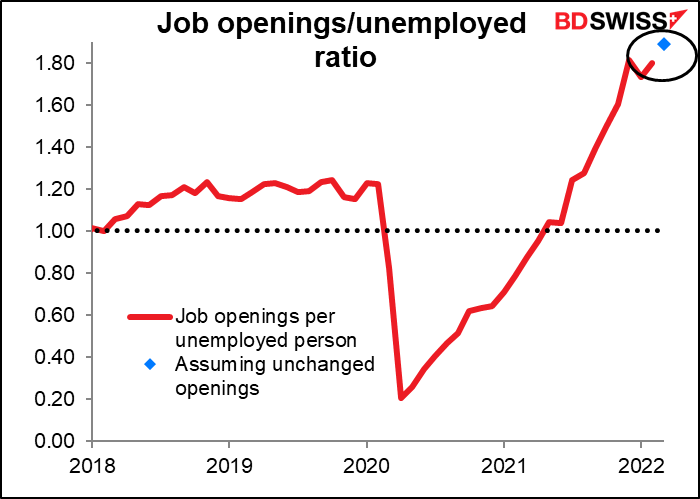

That view may get a boost from the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) on Tuesday. There are no forecasts yet for the figure, but if it turns out to be only unchanged, it would mean a record 1.89 job openings per unemployed person, up from 1.80 last month.

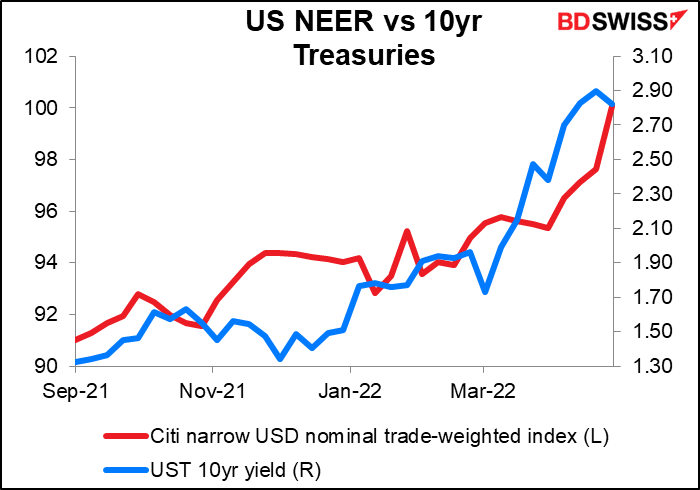

Getting back to Sly Stone, such evidence of an “extremely, historically tight” labor market would scream “higher” at the rates market. The dollar in turn is likely to dance to the music and continue to follow rates upward.

Other indicators: Tokyo CPI

JPY has had a rough time of it recently. On Thursday USD/JPY broke over 130 for the first time in almost exactly 20 years thanks to the Bank of Japan and its “yield curve control” (YCC) policy, which keeps the 10-year Japanese government bond yield capped at 0.25% while yields elsewhere skyrocket.

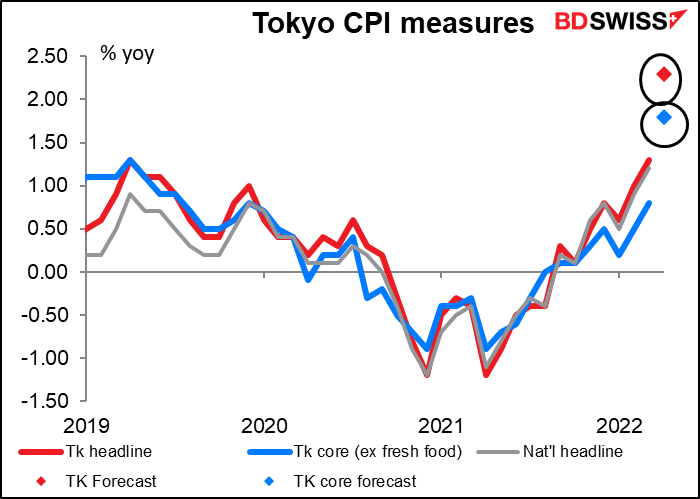

The Tokyo consumer price index (CPI) on Friday could cause some doubts to creep in about Bank of Japan policy. With the mobile phone charge cuts of April 2021 falling out of the calculation, the headline CPI is forecast to hit an astonishing (for Japan) 2.3% yoy, with the Japan-style core (excluding fresh foods) rising to 1.8% yoy.

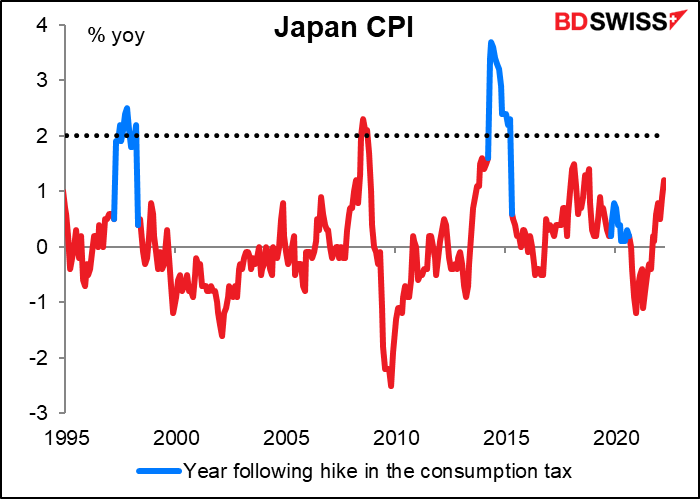

It’s unusual for Japan’s CPI to hit the 2% target. Except for right before the Global Financial Crisis, when the global economy was going gangbusters, the only times it’s happened since 1995 is in the years following a hike in the consumption tax – which naturally would cause consumer prices to rise.

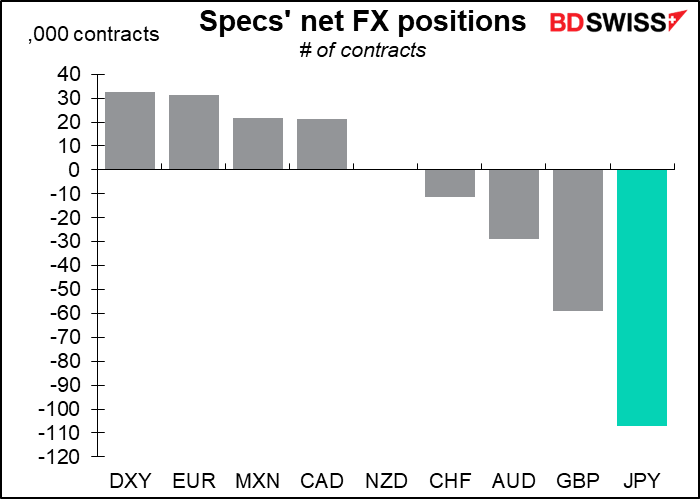

If people think this is a real change for Japan it could cause some short-covering among speculators that could push up the yen. According to the Commitments of Traders Report, speculators’ largest position in any currency right now is short yen.

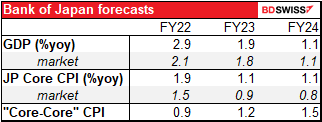

Unfortunately, this development was foreshadowed – and dismissed – in this week’s new edition of the quarterly Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices. It said:

The year-on-year rate of change in the consumer price index (CPI, all items less fresh food) is likely to increase temporarily to around 2 percent — due to the impact of a significant rise in energy prices — in fiscal 2022, when the effects of a reduction in mobile phone charges dissipate. Thereafter, however, the rate of increase is expected to decelerate because the positive contribution of the rise in energy prices to the CPI is likely to wane.

The “core-core” rate of inflation, which excludes energy as well as fresh foods, “is expected to moderately increase in positive territory.” So the best that they can hope for is for deflation to stop

Speculators could cut their short positions on this news, but I don’t think the Bank of Japan will change its stance, and without that the yen is likely to continue to decline.

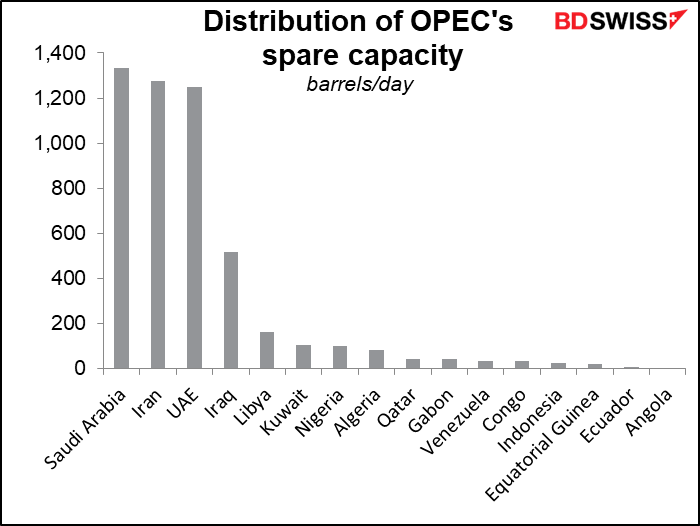

As for OPEC+, I think the market expects the group to stick to its existing plan and agree to another 432k barrel a day (b/d) increase in oil production. The fact is that most members are struggling to meet their quotas as is. OPEC+ rules forbid members with surplus capacity from compensating for those members who can’t meet their allotted quotas. There would be no point in the group as a whole voting to in effect allow Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iraq to pump more oil and thereby depress the price for the rest of them. (Iran also has significant spare capacity but can’t sell the oil because of sanctions.) I don’t think a decision along these lines would have much impact on prices because it’s probably well discounted already.