The key point for the markets of course is the Russian invasion of Ukraine. All other concerns are set aside for the time being.

The invasion will have a dramatic effect on markets through several channels.

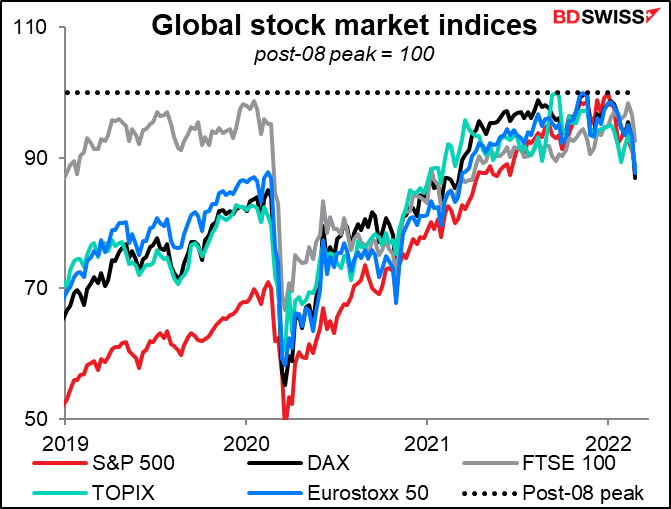

Risk aversion: Markets just don’t like war. Particularly not war in Europe. The disruption is bound to hit European growth and that’s sure to have ripples all over the globe. Europe, the US and other allies (Australia, Japan, South Korea) put sanctions on Russia, Russia puts sanctions on them, trade is disrupted, vital supplies are disrupted, and industries are upended. Markets get nervous and start to discount such events before they even happen. It’s impossible to predict exactly what will be affected so the impact is broad and blunt. The likely result: lower stock markets. As a result, major stock markets are down anywhere from 7.3% (FTSE 100) to 13.0% (DAX) from their recent peak (which in most cases is their record high).

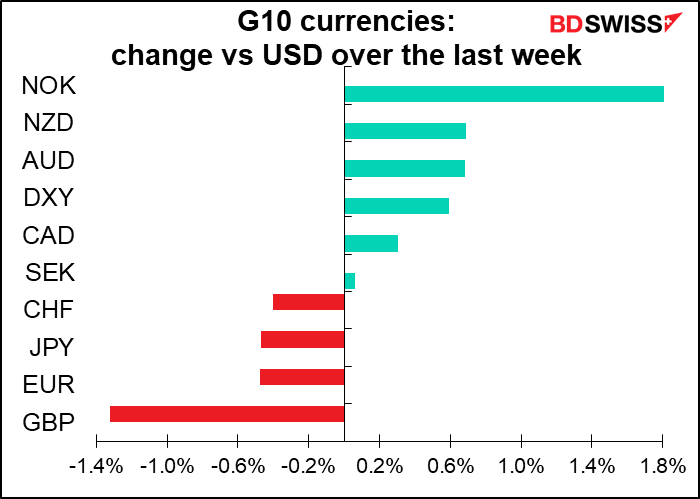

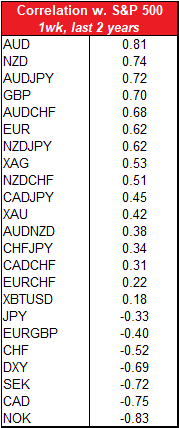

Looking at the weekly correlation between currencies and the S&P 500 up until the end of last year, a decline in stocks should in theory be worst for AUD, NZD, and GBP. Looking solely at the correlations it should be good for NOK, CAD, and SEK. Note that this is weekly correlation; on a day-to-day basis the figures are a bit different (AUD/JPY and NZD/JPY have the highest correlation on a day-to-day basis). Moreover CAD and even NOK haven’t been profiting much from the “risk-off” mood in the markets, contrary to what this correlation table would imply. Given the unique cause of this “risk-off” regime, we have to bear in mind the financial world truism that “past performance is no guarantee of future performance.”

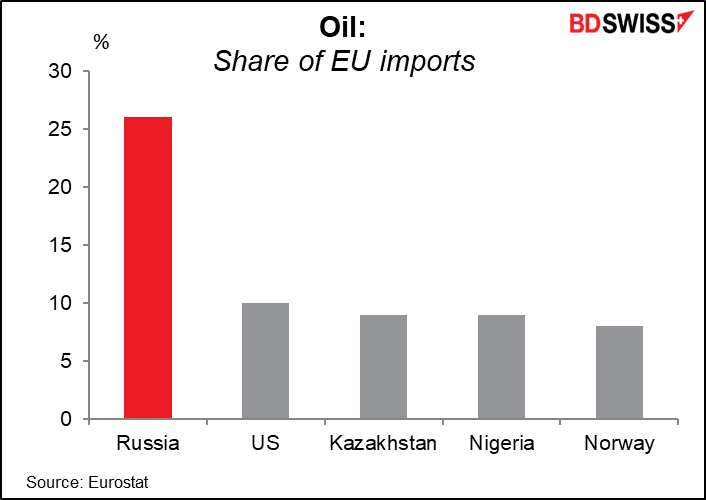

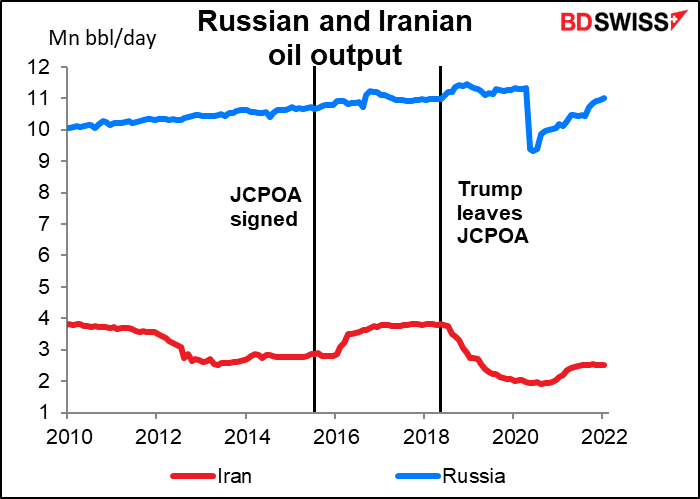

Energy: The big fear with Russia is its energy supplies. Russia produces around 11mn barrels of oil a day (b/d). This amounts to some 10% or more of global oil production. Historically they have been reliable oil exporters through both the Cold War and the Crimea Invasion, but market participants are worried that this may change. Either Russia may decide to use the energy weapon or other countries may embargo Russian oil Or perhaps the financial sanctions simply make it too hard to trade Russian oil. Owners of oil tankers may want to avoid dealing with Russian companies for fear of falling foul of the sanctions. Also restrictions on investment in Russia’s oil sector and export controls on technology may limit future supplies.

The concern over Russian oil supplies is partially offset by hopes in the market that Iran can reach an agreement with the US and Europe over its nuclear energy development that would allow sanctions to be lifted and Iranian oil to start flowing again. That might bring an additional 1mn b/d of oil or more onto the world market.

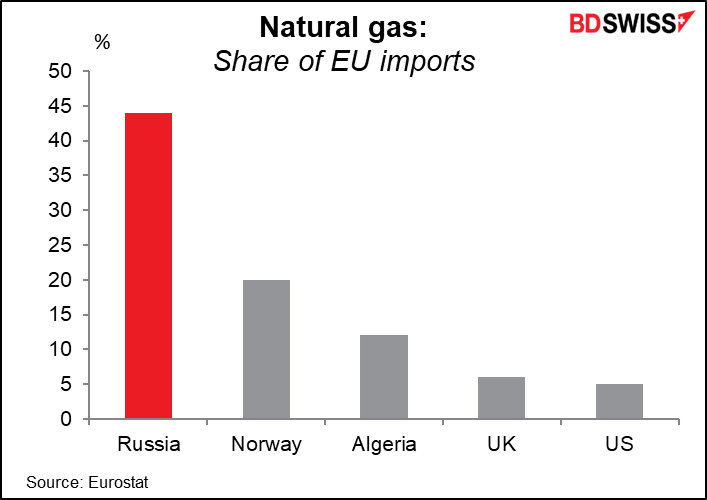

Russia is also a major supplier of natural gas, particularly to Europe, which gets 35%-40% of its total natural gas from Russia. Russia has already reduced its natural gas exports to Europe. Now that Germany has put the Nord Stream 2 pipeline on hold, Russia may retaliate by reducing the supply even further. This is probably not a big problem near-term as the end of winter approaches, but it could be a major concern if the fighting drags on until next winter begins with inventories at unusually low levels.

Any disruptions to the natural gas supply will in turn affect the production of energy-intensive products such as fertilizers, which are bound to hit agriculture. Furthermore, high energy prices make it more expensive to refine metals, especially aluminum.

Higher energy costs impact all countries but to differing degrees. There are a wide variety of estimates for how much a given rise in oil prices will dampen growth. A 2004 study by the European Central Bank (ECB) (Oil price shocks and real GDP growth: empirical evidence for some OECD countries) found that “an increase in oil prices has a significant negative impact on the GDP growth in all oil importing countries but Japan.” Japan’s resilience is counter-intuitive given the country’s total dependence on imported energy. It comes from its experience during the oil shock of the 1970s, which convinced the government to work sedulously to improve energy efficiency. Japan’s resilience to oil price rises will make the JPY an even more effective hedge in the case of higher oil prices.

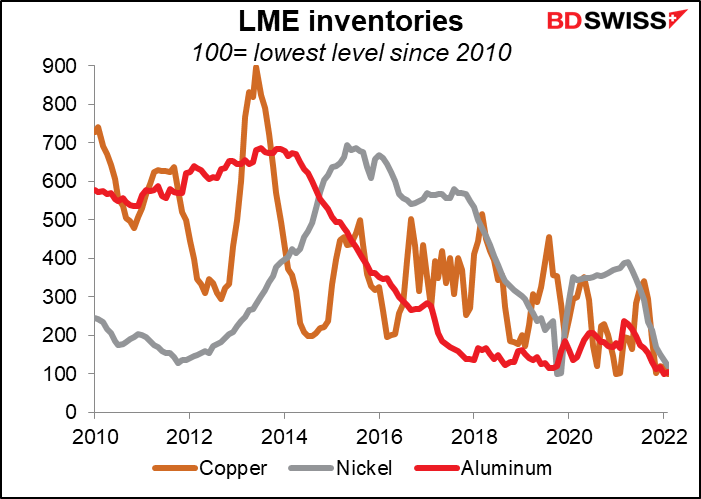

Metals: Russia is a major producer of industrial metals, including palladium (40% of global supply), platinum (12%), nickel (5%-7%), aluminum (4%-6%), and copper (3%). Inventories of most metals are at extremely low levels and so vulnerable to a supply crunch. Higher metal prices will probably mean higher prices for many products. In particular, clean energy may suffer a setback as batteries use palladium and nickel, while hydrogen-based energy systems use platinum as a catalyst.

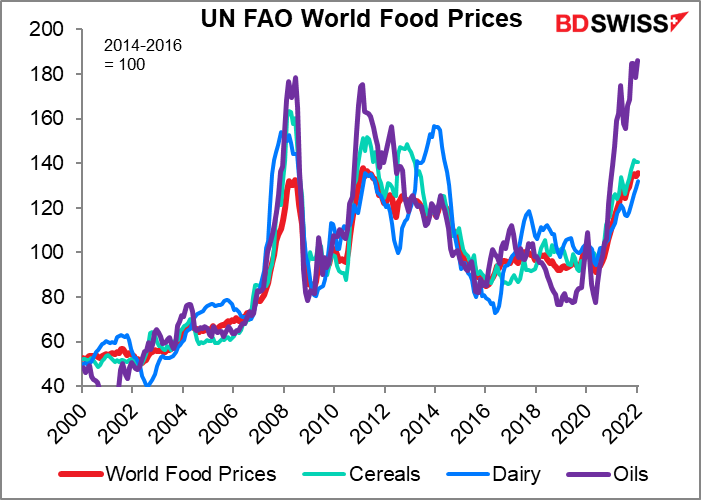

Grain & foodstuffs: An equally large threat comes from Russia and Ukraine’s supply of grain and foodstuffs. In 2019, Russia was the world’s largest producer of barley; the third-largest producer and the largest exporter of wheat; the second-largest producer of sunflower seeds; the third-largest producer of potatoes and milk; and the sixth-largest producer of eggs and chicken meat. Russia and Ukraine together supply around 29% of the world’s wheat exports, 14%-20% of corn exports (depending on who you listen to), and 80% of sunflower oil exports. These supplies are even more vulnerable than oil supplies as farmers flee the fighting and infrastructure and equipment are destroyed.

This is not just a problem for Europe, which gets 4.9% of its imported food from Ukraine. It’s a particular problem for the Middle East, which relies heavily on imports of wheat from the two countries. Rising grain prices could spur instability in Egypt, Turkey and many other countries in North Africa. Remember the “Arab Spring” in 2011, when rising food prices sparked riots & revolutions across the region?

Food is also a bigger concern than energy for central banks, at least in the short term. That’s because it has a larger weight in the basket of goods that the consumer price index is based on. For example, in the Eurozone food has a 166.46 weight, more than double the 65.88 weighting for electricity, gas, and other fuels (total basket = 10,000). In the US, food has a weight of 13.37, almost double the 7.35 for energy (total basket = 100). The problem is that demand for food is relatively inelastic and so raising interest rates doesn’t do much to dampen demand or otherwise affect prices.

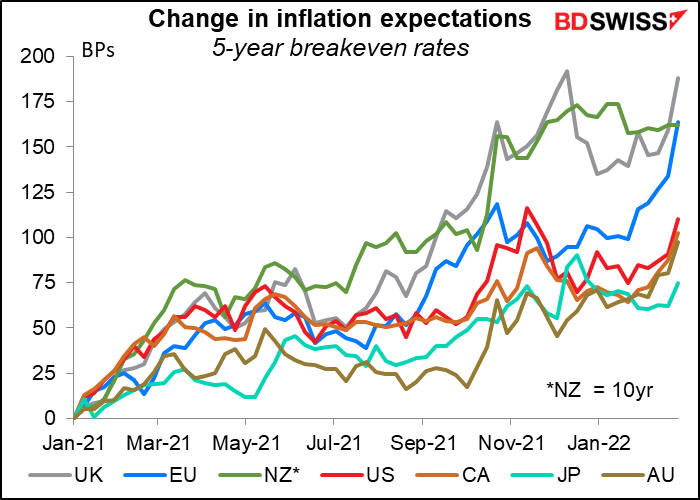

Fears of higher energy and food prices have pushed up inflation expectations, especially in Europe and the UK.

Other commodities: There may be vulnerabilities that we don’t know of yet until they’re made apparent, just as the auto industry’s vulnerability to Malaysian health problems didn’t show up until the virus started crimping the production of microchips there. For example, the US semiconductor industry relies heavily on Ukranian supplies of the gas neon. Russia also exports a number of elements critical to manufacturing semiconductors, such as palladium, as mentioned above.

Other issues:

Flights: Over 300,000 flights used Russian airspace for transit in 2019 as routes between Europe and Asia want to avoid flying over Syria and Iraq. During the Cold War, Russia closed its airspace and airlines had to fly via Anchorage. Alaska. This could add to the time & cost for passengers and air freight.

Cyberwarfare: Russia has used cyberwarfare against Ukraine. In 2015 and 2016, hackers attacked Ukraine’s power grid and turned off the lights for up to six hours in Kyiv. The 2017 NotPetya cyber attack was initially directed at Ukraine private companies before it spilled over and destroyed systems around the world, causing more than $10bn worth of damage, according to US estimates. And this past January, hackers disrupted dozens of Ukrainian government websites in addition to placing destructive malware inside Ukrainian government agencies. Cyber attacks by either side could not only disrupt trade and production but also spill out over the borders and again cause global disruption.

Russian FX reserves: Russia has been preparing for an event like this for some time and has some $630bn in foreign exchange reserves, including $469bn in foreign currency reserves and $132bn in gold. This is equivalent to some two years’ worth of imports. Most of the foreign currency reserves are in EUR (32%) and USD (16%). If the country had to sell off its reserves to finance imports then the impact would probably fall most on EUR and gold.

Taiwan: The biggest issue that I see coming out of this whole episode has nothing to do with Russia or Ukraine. It’s this: if China sees Russia getting away with invading Ukraine, will it try to take over Taiwan? As an article in The Atlantic put it, “Just as Putin can’t tolerate Ukrainian sovereignty, the Chinese Communist Party will never accept the separateness of Taiwan.” So far China has refrained from even calling Russia’s actions an invasion. Instead a foreign ministry spokeswoman said, “Regarding the definition of an invasion, I think we should go back to how to view the current situation in Ukraine. The Ukrainian issue has other very complicated historical background that has continued to today. It may not be what everyone wants to see.” I can think of other international relationships that have “very complicated historical background.”

Taiwan doesn’t produce the broad range of commodities that Russia and Ukraine do, but it does have a stranglehold on one essential part of the modern global economy: it accounts for 92% of the world’s most advanced semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Most of what Russia produces can be obtained elsewhere, albeit at a price. Not so with Taiwan. Look at the chaos that’s ensued in the world today from a shortage of microchips. Imagine the impact on the global economy from almost no microchips available.

Speaking of which, Taiwan’s participation in the international sanctions may well be the most effective leverage that the West has against Russia.

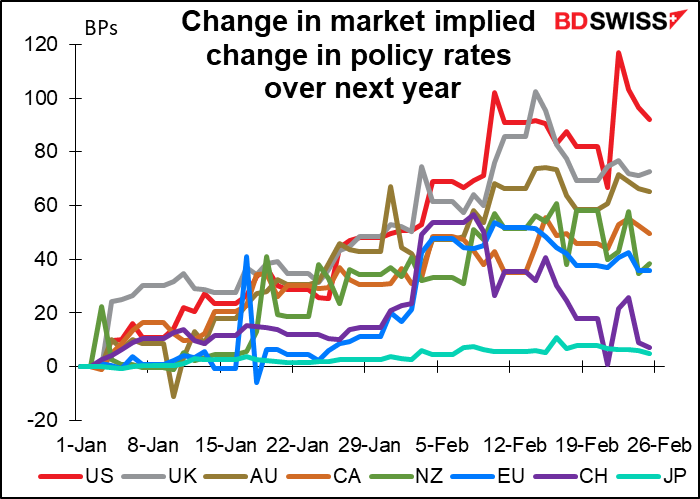

Implications for currencies: The big question for most currencies is how central banks are likely to react to the impact of the invasion. Do they focus on the inflationary impact of higher energy and food prices, or do they focus on the likely hit to growth from weaker stock markets and lower business & consumer confidence? The reading so far is the latter: less expected tightening over the next year.

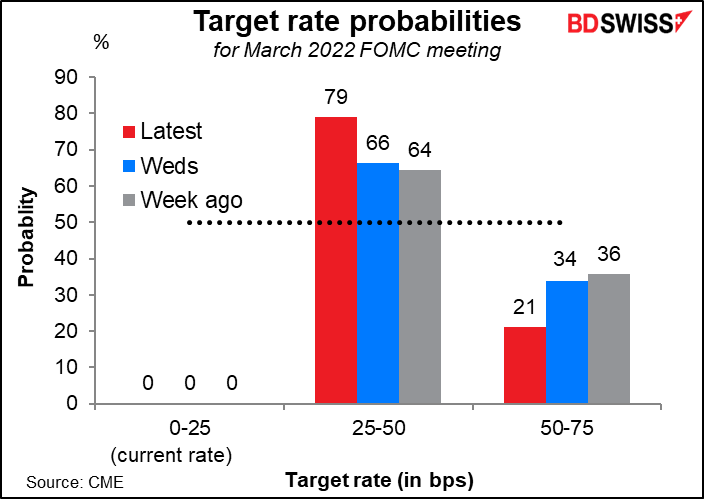

For example, the market’s view on the likelihood of a 50 bps hike at the March FOMC meeting has declined considerably. On Feb. 10th, following the blowout January US consumer price index, a 50 bps hike was seen as a near-certainty (94% probability).

That’s the guidance officials are giving, too. Cleveland Fed President Mester (V), one of the more hawkish members of the Federal Open Market Committee, said that “the implications of the unfolding situation in Ukraine for the medium-run economic outlook in the US will also be a consideration in determining the appropriate pace at which to remove accommodation.” And in Europe, Austria Central Bank Gov. Robert Holzmann, one of the ECB’s biggest hawks, made similar comments in an interview with Bloomberg. “It’s clear that we’re moving toward normalizing monetary policy. It’s possible however that the speed may now be somewhat delayed.”

Implications of the invasion:

SHORT-TERM IMPACT (1-2 months)

MEDIUM-TERM IMPACT (3-12 months)

LONG-TERM IMPACT (beyond one year)

Next week: RBA, Bank of Canada, Powell testimony, NFP, OPEC+ meeting

There would be plenty to talk about next week even if it weren’t for the fighting in Ukraine. Just to discuss the main points briefly:

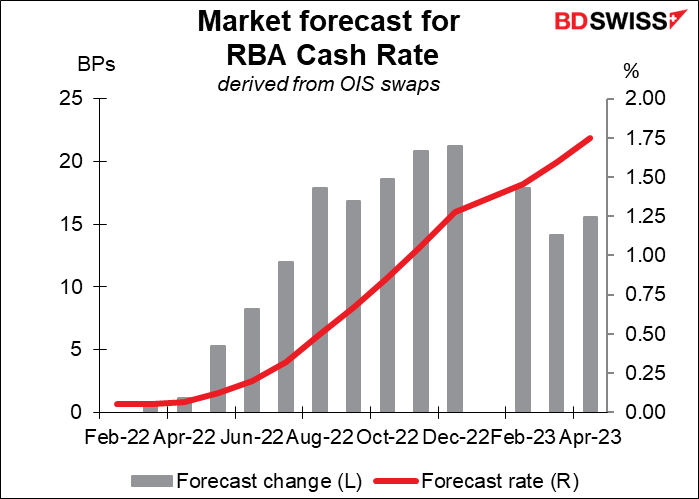

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) meeting Tuesday: snore

The RBA’s March board meeting is likely to be a non-event for market participants. The market doesn’t expect a change in rates until the July meeting at the earliest. Nor is there likely to be an announcement on the bond purchase program at this meeting, as that’s scheduled to be decided at the May meeting. Nor has the data since the last meeting done anything to change their view – on the contrary, the weaker-than-expected increase in wages in Q4 will only confirm their narrative that higher wage pressures are necessary to get inflation into its target range sustainably. All in all the tone of the statement should be little changed from February and therefore have little impact on the currency.

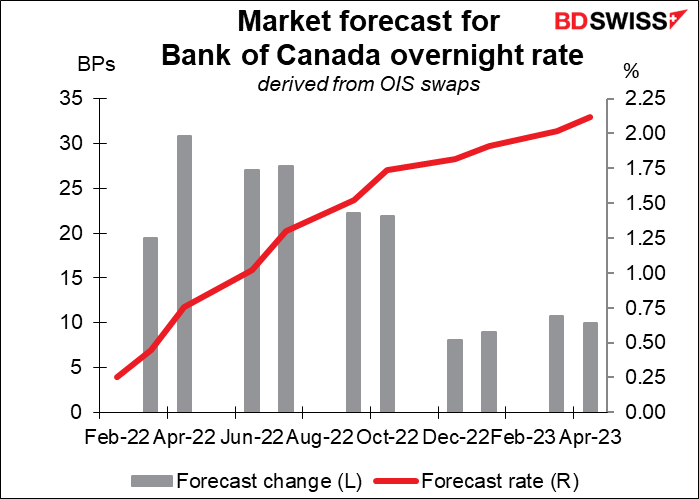

Bank of Canada meeting: first rate hike expected

The Bank of Canada on the other hand is generally expected to hike its overnight rate by 25 bps to 50 bps. At its last meeting in January, the Governing Council said it “expects interest rates will need to increase,” and all 25 economists polled by Bloomberg expect that process to begin this week.. Canada isn’t much affected directly by the fighting in Ukraine, although higher oil prices may give the economy somewhat of a boost (as well as increasing inflationary pressures). With headline inflation now 5.1% and the average of the three core inflation measures 3.2%, above the 1%-3% target range, it’s time to get started. The impact on the markets then will depend on what they imply about the future course of tightening and what if anything they intend to do with their balance sheet, which increased by far and away the most of any major central bank following the pandemic.

Powell testimony: What’ll he say?

Fed Chair Powell gives the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress to the House of Representatives on Wednesday and to the Senate on Thursday. He’s bound to be grilled on inflation, which the Republicans are likely to carp on and on about (you don’t hear them asking many questions about employment), and pressed on how the fighting in Ukraine will affect their plans to normalize policy. Look for him to repeat something non-committal like what Cleveland Fed President Mester said quoted above (“the implications of the unfolding situation in Ukraine for the medium-run economic outlook in the US will also be a consideration in determining the appropriate pace at which to remove accommodation.”)

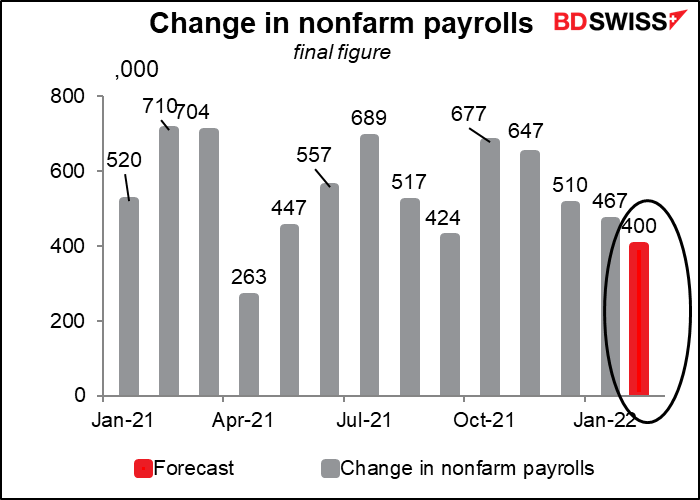

Nonfarm payrolls: still growing

Friday’s US nonfarm payrolls figure is expected to show an increase of 400k jobs. While below the recent pace of growth, that would still be a healthy increase that would give the Fed no reason to doubt that the US is at “maximum employment.” Indeed the slight drop in the number of new jobs might be interpreted as meaning that there are fewer and fewer people left who want to work but can’t find a job. Accordingly, watch the participation rate as well.

Growth in average hourly earnings is expected to rise further to 5.8% yoy from 5.7%, fuelling fears of a wage/price spiral. That’s another reason for the Fed to tighten = USD+.

OPEC+ meeting Wednesday: stick to the plot

Look for OPEC+ to raise output by another 400k barrels a day, on schedule. The only problem is of course that even if they raise everyone’s quota accordingly, not all members can meet their higher quota, so total output won’t increase by that much.

Other indicators out during the week include: