The Russia/Ukraine conflict is spilling over into the rest of the world.

There are other countries that are isolated from the world to some degree: North Korea, Iran, Cuba, Venezuela. But none of them have been as integrated into the world economy as Russia is. It’s the 16th largest trading country in the world: #18 for exports, #13 for imports (excluding Netherlands, Hong Kong, and Singapore, which have large trade accounts due to their ports). Iran’s total trade before the embargo in 2012 was $187.6bn. Last year it was $36.4bn. Russia was $569.2bn. Whole regions depend on it for some goods: Europe gets 44% of its natural gas and 26% of its oil from Russia. More than a dozen countries in the Middle East and Africa rely on Ukraine for more than 10% of their wheat consumption. With Russia now being in effect evicted from the global economy, we are seeing an experiment whose outcome we can’t predict.

One example of unforeseeable consequences: remember the terrible earthquake in Japan in 2011? There were several factories in the region making specialized steel for car shock absorbers. With no other suppliers available anywhere, the earthquake shut down global auto production. Similarly with this economic earthquake there are bound to be unforeseeable impacts, except it’s on a much larger scale. No country of this size and importance, this deeply integrated into the global economy, has ever faced this kind of global freeze-out.

The crisis has two aspects: the economic crisis within Russia on the one hand and the worldwide ripple effects that we’re already starting to see.

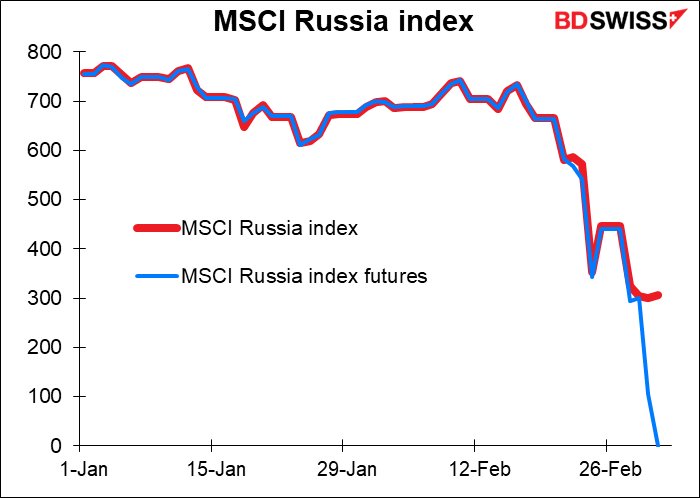

The Russian stock market is closed so we don’t know what the domestic value of Russian stocks are. The MSCI Russia index is down 60% but the futures have gone to zero.

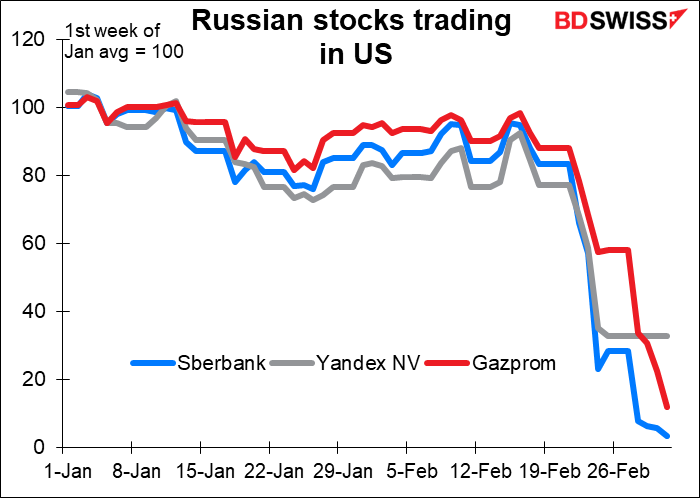

Overseas the value of Russian companies has evaporated. One trader on Twitter complained that he wanted to buy Sberbank at 1 cent, but his broker said they were only accepting sell orders, not buy orders. I’m not sure how that works. Then again, I’m not sure anyone has much experience with a situation like this.

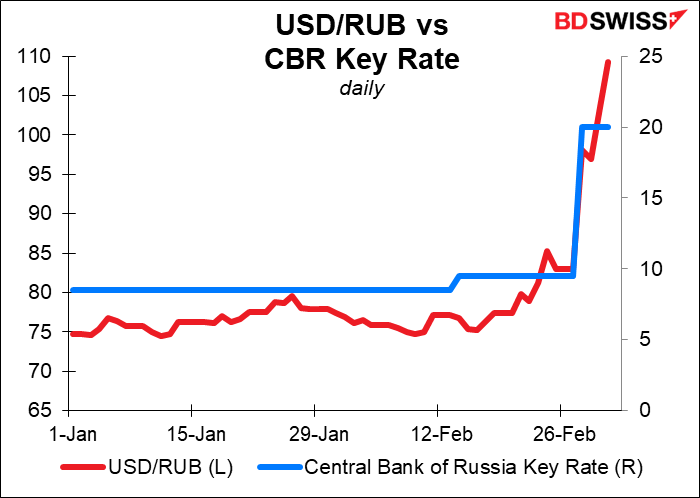

…as has the ruble, even after the central bank more than doubled the overnight rate in an attempt to shore up its value. What will these higher interest rates do to the economy?

We’ve yet to see how the sanctions will work. How much of the country’s $231bn in annual imports will be affected?

For example: Airbus and Boeing said they would stop supplying Russia with spare parts. The two manufacturers account for two-thirds of the country’s air fleet. Meanwhile, Western leasing firms will try to repossess the 515 planes that Russian carriers lease. What happens to a country of Russia’s size when there are no planes? Eventually domestic manufacturers will replace them (although it’s not certain they can without imported components). But until then, how will Russians get around? How will they import goods, components, raw materials, and food with no planes, about half of all shipping lines unwilling to deal with them, no insurance companies willing to insure the cargoes, no banks willing to provide trade finance? Russia is also a huge exporter of grains, but 40% of seeds are imported (90% for potatoes, a major crop).

ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP have all announced their exit from the country. What will that do to the long-term growth prospects of Russia? Not to mention that the government depends on oil taxes for 36% of its revenue.

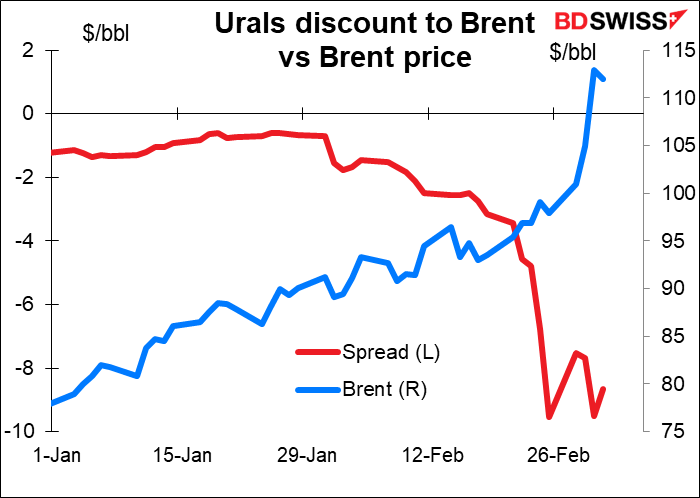

Internationally, the invasion has sent prices of commodities supplied by Russia and Ukraine soaring. The price of Brent crude is up 42% year-to-date already. Russia’s Urals crude is priced at a record discount to Brent, but according to press reports there are no takers – no one will buy the oil, no one will charter a ship to carry it, and no one will insure the cargo. One Singapore-based multinational commodity trading company reportedly offered a cargo of Urals at a staggering discount of $18.60/bbl to Brent but there were no buyers even though the transactions wasn’t with a Russian company. Although the sanctions apparently exclude energy exports, there seems to be an informal embargo developing as no one wants to take the risk – not even the Chinese.

Coal also hit a record high on Wednesday, up 80% this year alone. Although China is the main importer of Russian coal and China has been less enthusiastic about signing on for the sanctions, most banks have stopped issuing letters of credit after Russia was kicked out of the SWIFT bank messaging system. As almost all contracts are dollar-denominated, there is no other way to make the payments.

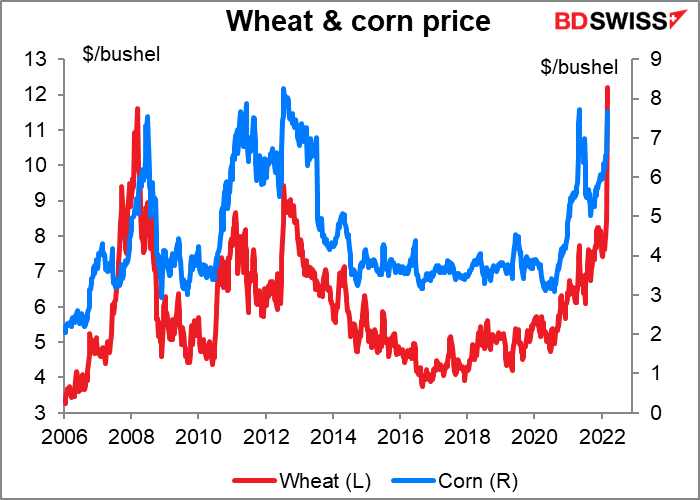

Grain prices have soared as well. Wheat futures went limit-up to hit a record high. Corn is 7% off its record high. This will affect millions of people, especially poor people.

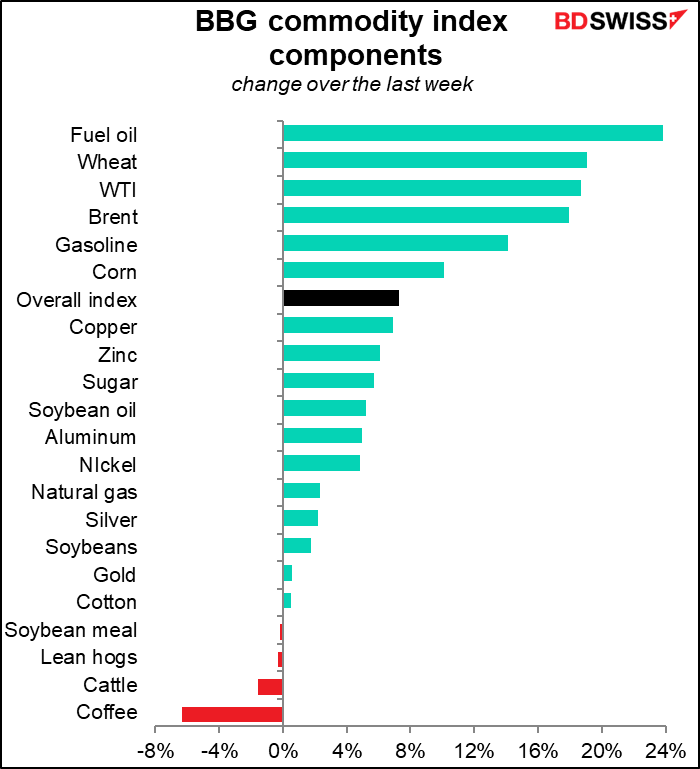

The rise is widespread across a variety of commodities.

As a result, inflation expectations rose around the world.

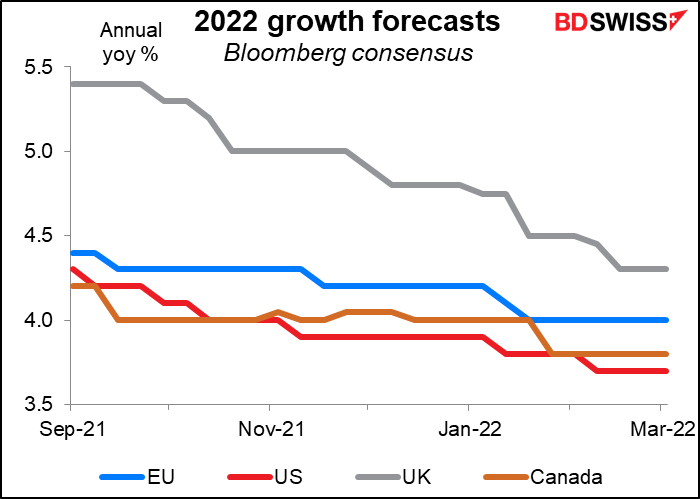

These higher prices pose a danger to the global economy that markets are now beginning to discount. Higher prices act as a tax on consumers, draining away money that they would otherwise spend on other activities. Money that goes to gasoline and bread is money that doesn’t go on movies and iPhones. As a result, the market has been revising down growth expectations for several (but not all) of the major economies.

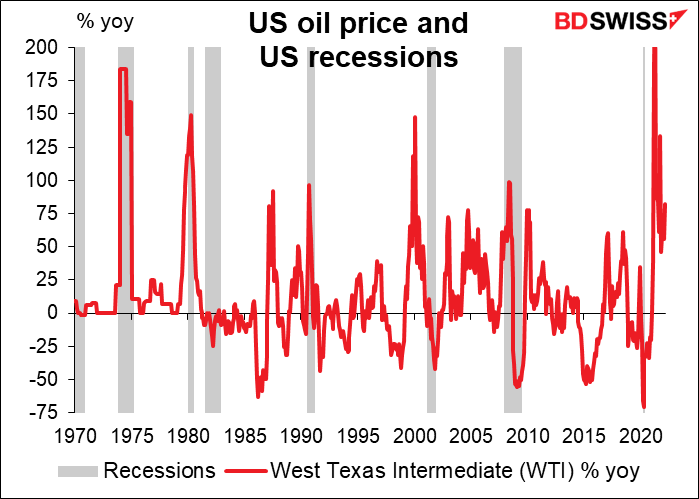

Investors are particularly worried about the impact of higher oil prices on the global economy. Not every sharp rise in oil prices has resulted in a recession, but every US recession has been preceded by a sharp rise in oil prices. And this has been one of the sharpest rises ever.

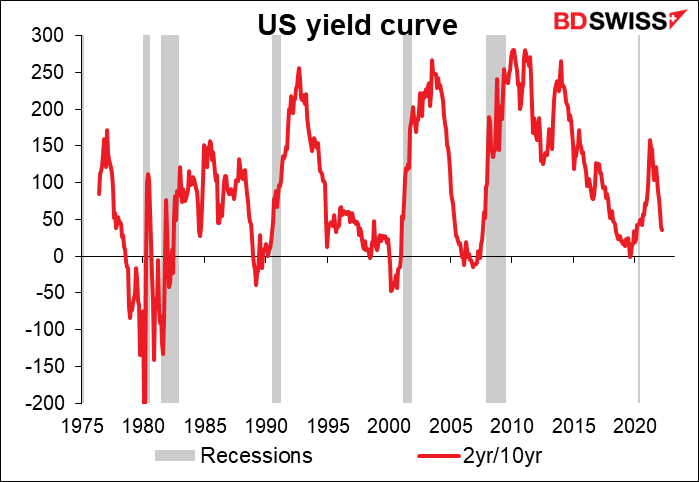

The US yield curve is also near, but not yet at, the level that generally presages a recession. The 2yr/10yr curve hit a post-pandemic low this week. Note though that unlike oil prices, the yield curve doesn’t cause a recession, it only predicts one.

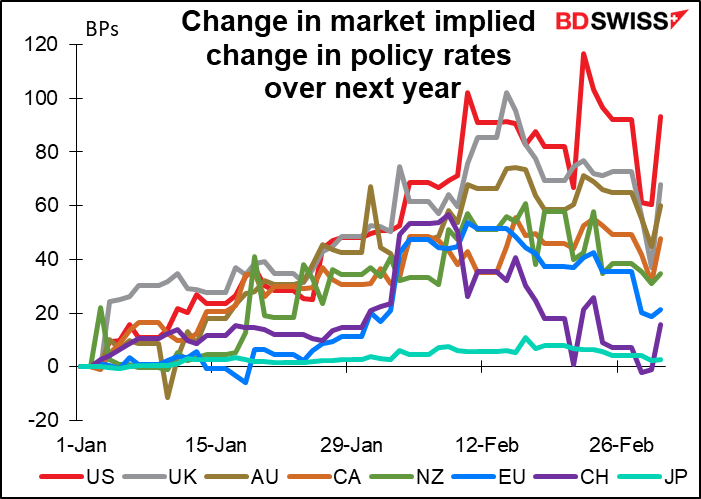

The fear of recession – and what it might mean for central bank policy – caused extremely volatile moves in central bank policy rate expectations, with expectations plunging on Monday and Tuesday but bouncing back again on Wednesday as sentiment improved somewhat.

Central bankers are in a pickle. They have tools to fight recession (lower interest rates, quantitative easing) and tools to fight high inflation (higher interest rates), but they don’t have appropriate tools to fight both at the same time It’s an either/or situation. Since Europe is the center of the fighting and the European economy is the most deeply integrated with Russia (particularly with regards to energy), the European Central Bank (ECB) faces the most difficult balancing act of all the major central banks.

What we learned from the stagflation era of the 1970s/early 1980s is that fiscal policy will have to be used to buffer the economy from the energy shock and support investment in energy infrastructure and defense (especially in Europe). That leaves monetary policy to deal with inflation.

What are the implications for markets?

This coming week: ECB, US CPI, and of course Russia/Ukraine

Once again the economic statistics that I so lovingly follow, that I’ve dedicated my life to examining and understanding, are of little importance to the markets. Everything will focus on the war in Ukraine. Yes, I do feel at such times as if my work is pointless and my existence contributes nothing to humanity except perhaps that it allows me to pay my daughter’s school fees. Plus send her money to go out with her friends, which I suspect she appreciates more.

Putting aside the futility of this transitory existence, the main scheduled event for the markets this coming week will be the meeting of the European Central Bank (ECB).

The big question they will address at this meeting is, how will the fighting in Ukraine affect the inflation outlook? The impact isn’t clear. On the one hand, surging commodity prices as outlined above increase the risk of higher inflation lasting longer than anticipated. On the other hand, the increase in uncertainty caused by the fighting is likely to dampen the economy, not to mention the drain on spending caused by higher food & energy prices.

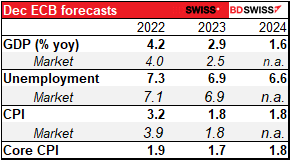

They will get new staff forecasts at this meeting. These forecasts were made using data up to Feb. 15th, before the invasion, so to some degree they’re already out of date. However ECB Chief Economist Lane said in a recent speech that the staff would take into account the most recent data and events in setting the forecasts.

In normal times, if the crucial 2024 forecast for inflation is at the 2% target or above, that would trigger the start of policy normalization.

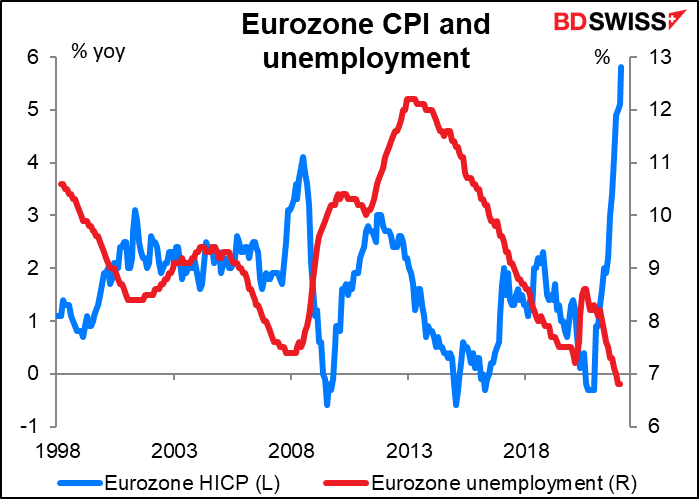

With record-high inflation and record-low unemployment (from the start of the Eurozone in 1998) normally they would’ve announced at this meeting that they were ending one of their bond purchase programs on schedule at the end of March and tapering down the other one more rapidly than planned. They’ve said they would end the purchases “shortly before we start raising the key ECB interest rates.”. They could then begin discussing how long “shortly before” means.

This time however they are likely to put the normalization process on pause while they wait to see how things develop in Ukraine. ECB Chief Economist Lane noted in his latest speech that they won’t have all the information that they need on March 10th. However, this would just mean policy normalization is delayed, not derailed.

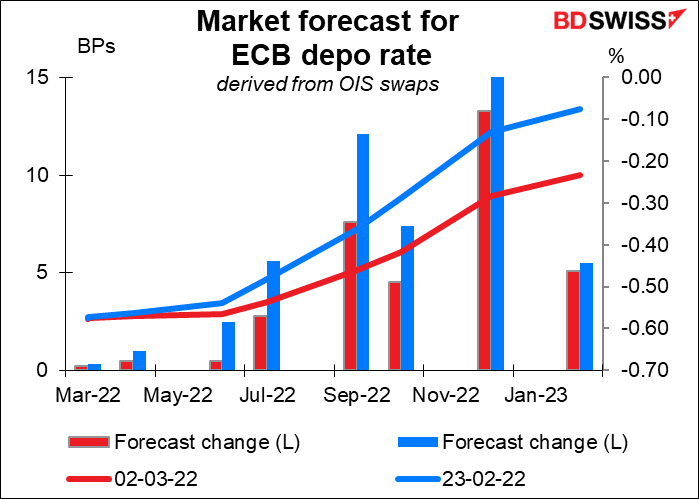

That idea seems to be in the market already. Expectations for rate hikes have calmed down considerably even over the last week. The market had been expecting the first rate hike to come at the September meeting; now it seems to be penciled in for the December meeting. But still penciled in

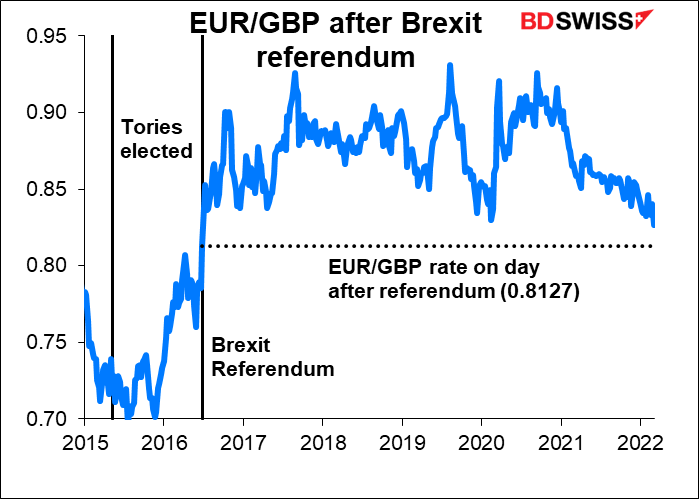

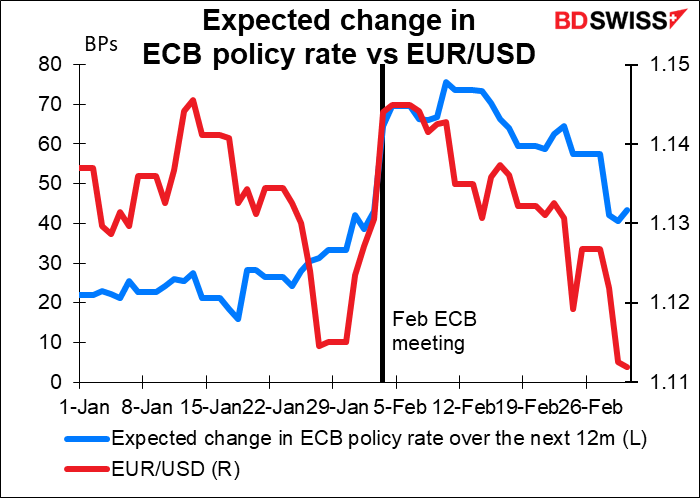

The market reaction is therefore likely to depend on what they say about the fighting and how long it’s likely to delay them. I suspect that they stress that their decision will depend on the duration and extent of the Ukraine conflict, which no one has any solid insight into. The delay to “lift-off” is likely to weaken the euro further, in my view.

Other major EU indicators are Germany factory orders (Mon) and industrial production (Tue).

The other big event of the week is the US consumer price index (CPI), also on Thursday. It’s expected to soar further to 7.9%. Each month we have to go back a month or two earlier to say “this is the highest rate of inflation since…” Last month it was the highest since Feb. 1982 (7.6%); this month is expected to be the highest since January 1982 (8.4%).

It comes exactly a week before the meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee and so will set the tone for that meeting. But Fed Chair Powell already told Congress that he would propose a 25 bps rate hike at that meeting. Nonetheless, if it beats expectations (as usual: 8 beats, 4 equals, 1 miss since Jan. 2021), it could increase expectations for rate hikes later in the year which could be positive for the dollar.

Other major US indicators out during the week include the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) program on Wednesday, which will tell us about the labor market from the demand side, and the University of Michigan consumer sentiment survey on Friday.

UK short-term indicator day on Friday will feature January GDP as well as the usual industrial & manufacturing production and trade data. Growth momentum was slowing at the end of the year under the weight of the omicron variant and the market expects no change in output for January. Household consumption has been slowing as the cost of living rises, plus business investment remains pretty sluggish. Finally, some of the growth came from increased health spending thanks to more testing and vaccinations – that too has fallen off. Still, I think as long as output doesn’t contract in January the Bank of England is likely to remain on a tightening trend. That should be positive for GBP.

Other indicators out during the week include Japan current account (Tue), China PPI and CPI (Wed), and Canadian employment (Fri).