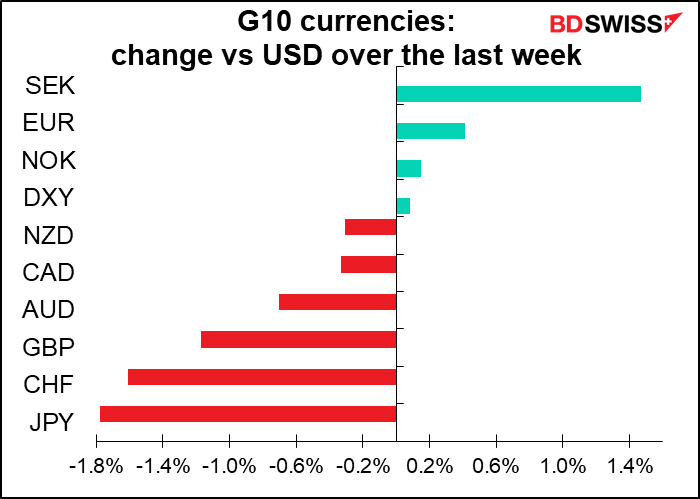

As the war in Ukraine drags on, commodity prices have soared, inflation looks to be higher than anyone expected for longer than anyone expected, and growth will inevitably be lower than anticipated. What are central banks likely to do in this situation?

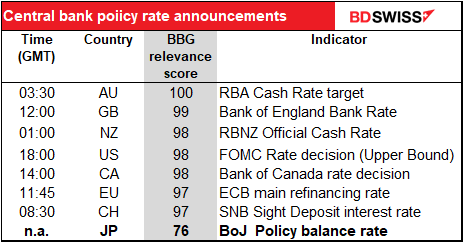

We heard from one this past week – the European Central Bank (ECB) – and we’ll hear from three next week: the US Fed (Wednesday), the Bank of England (Thursday), and the Bank of Japan (Friday). If the ECB is any guide, the first two are likely to raise interest rates. The Bank of Japan not yet, but it will be interesting to hear what they have to say on the matter.

Given the uncertainty ahead, I had expected the ECB to keep policy on hold. However they decided to start a few small steps toward normalizing monetary policy (which I won’t go into here as I’m sure it’s well covered elsewhere.) That gives us a hint of what we can probably expect next week.

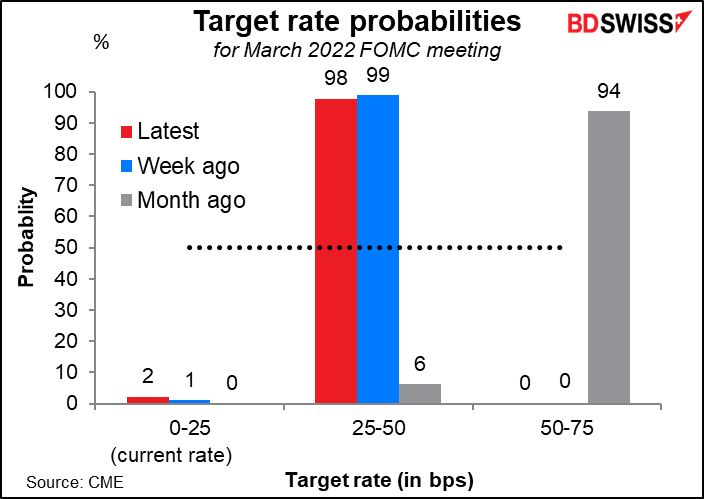

Next up is the US Federal Reserve, whose rate-setting body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets on Tuesday and Wednesday. Fed Chair Powell already said he’s going to recommend a 25 bps hike in rates at this meeting, the first rate hike since December 2018. The market now puts a 98% probability on this happening. That’s a big turnaround from a month ago, when the market saw a 94% probability of a 50 bps hike.

The three questions the market will be looking for answers on are:

- How many more rate hikes after this?

- When will they start reducing the size of their balance sheet? And

- How much will they reduce it by each month?

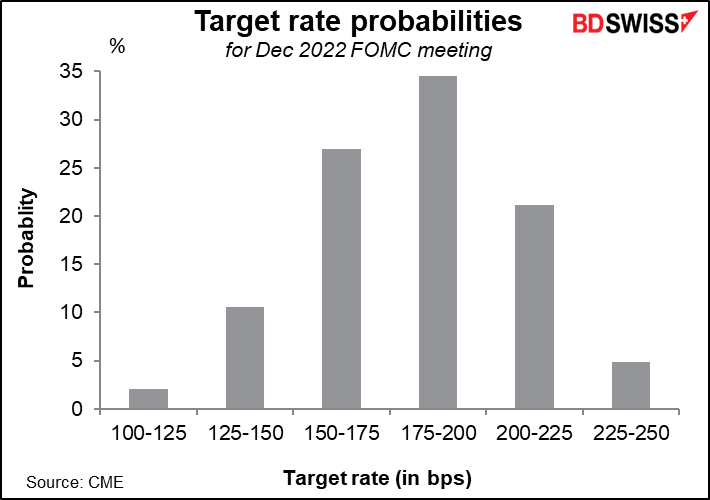

As for the first question, the market puts the highest probability on seven rate hikes of 25 bps each this year, bringing the Fed funds rate to 1.75%-2.0%. That would imply one rate hike of 25 bps at each meeting for the rest of the year, which is certainly conceivable.

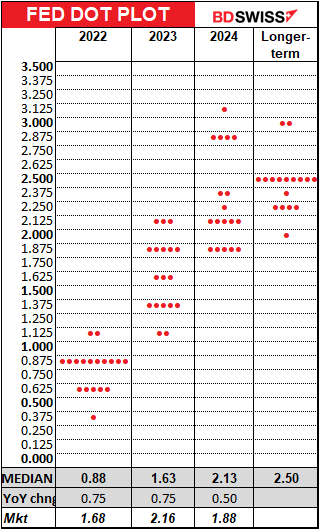

That would still leave the fed funds rate below what the FOMC members consider to be the “neutral” rate – 2.5% — at which they are neither stimulating nor restricting the US economy. The market doesn’t expect them to get that far – the fed funds futures peak at 2.16% in December 2023 and start to decline after that, implying that they think the Fed will have to start easing policy before they can even get to neutral.

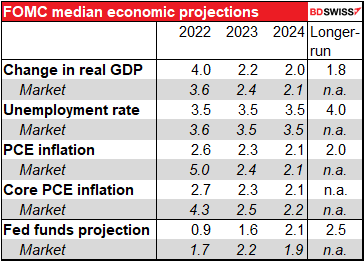

This meeting will be accompanied by an updated version of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), which as you might expect is a summary of the Committee’s economic projections. Of particular concern as usual is their forecast for inflation.

And with that comes the notorious “dot plot” in which each member forecasts where he or she expects the fed funds rate to wind up at the end of each year. The market will be itching to see how the median Committee member is thinking relative to what the market is thinking. As it stands now the market is more aggressive than the Committee for this year and next year but expects the Fed to have to ease in 2024. This is contrary to the Fed’s hope that it can engineer the fabled “soft landing” and pilot the economy toward equilibrium. Hah! It hasn’t happened yet, but maybe it will this time. As we all know, past performance is no guarantee of future performance.

As for the balance sheet, they said at the January meeting that they’re going to reduce it “in a predictable manner” by allowing bonds to mature without being rolled over, rather than selling bonds. The question then is how much they will allow to mature in this way each month – the cap on maturing bonds. In his recent testimony to Congress, Chair Powell said that at this meeting “we’re going to set a pace at which runoff will happen subject to caps.”

The question of when to start running down the balance sheet is another matter. Different members have expressed different views. The minutes of the January FOMC meeting only mention starting to reduce it “sometime later this year, “ a phrase that NY Fed President Williams (V) echoed in a speech last month. They may try to be a bit more specific than that as this meeting while still leaving themselves plenty of wiggle room should events turn out differently than they hope.

Last time around the first mention was in June 2017 when they said “The Committee currently expects to begin implementing a balance sheet normalization program this year, provided that the economy evolves broadly as anticipated.” At the next meeting, In July, they said “The Committee expects to begin implementing its balance sheet normalization program relatively soon, provided that the economy evolves broadly as anticipated…” Then at the next meeting, September, they said “In October, the Committee will initiate the balance sheet normalization program…” Given where inflation is now, they may skip “this year” and go straight to “relatively soon,” hedged of course with a variety of caveats about the geopolitical situation.

Market impact: The market obviously expects a 25 bps hike. The reaction then will be dictated by 1) how much the dot plot changes and 2) how aggressive they seem on running down their balance sheet. Given the bipartisan pressure to get inflation down, I expect that Fed Chair Powell will not pull any punches in his press conference. That could be positive for the dollar.

Bank of England: can they match the market?

There doesn’t seem to be any doubt in anyone’s mind that the Bank of England will raise its Bank Rate by 25 bps at its meeting next week. The question is, how quickly are they likely to raise rates after that?

Note that while the market has priced in a 25 bps hike at this meeting, it’s pricing in a 37 bps hike at the May meeting and a 33 bps hike at the June meeting. In other words, a good chance of a 50 bps hike at one of those meetings.

This assumption comes from the fact that at the last meeting, in February, four of the nine members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted for a 50 bps hike. But would they still vote that way? It’s by no means certain. For example, Michael Saunders said recently that “My preference for a 50bp hike at the February meeting does not necessarily imply that I will vote for 50bp steps in the event that rates have to rise further.”

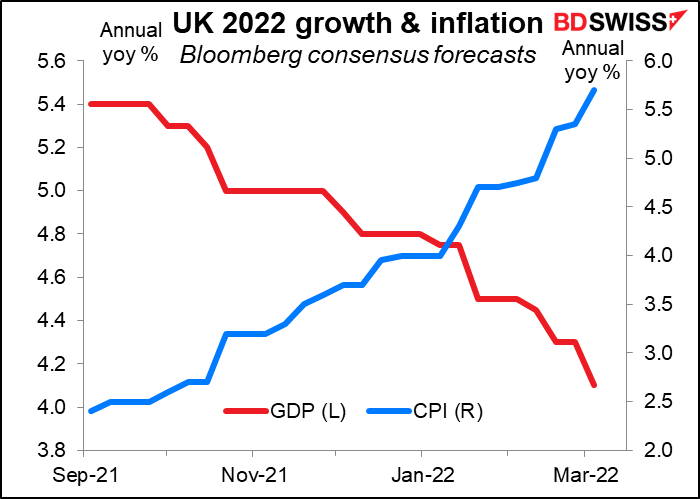

Most MPC members seem to agree that the war in Ukraine has raised the outlook for inflation in Britain. At the same time it has raised the uncertainty around the economy and reduced growth expectations.

Do they want to risk adding an interest rate shock to all the other shocks the country is suffering from? A large (63%) proportion of UK households own their own home and most mortgages are floating rate, meaning an interest rate hike immediately hits peoples’ pocketbooks.

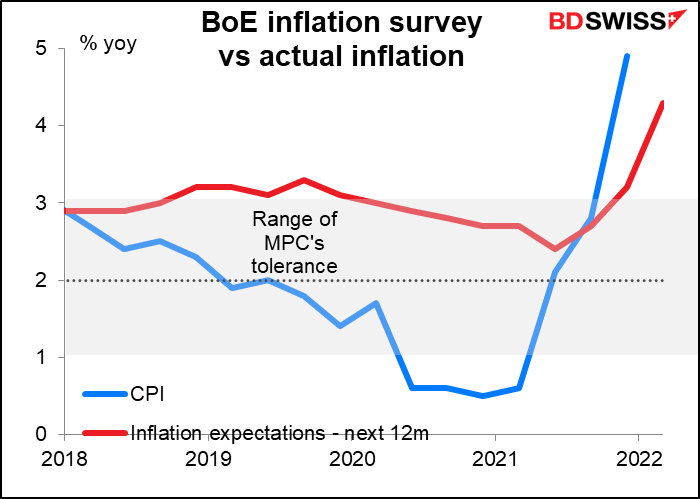

On the other hand, do they want to risk inflation expectations becoming “embedded” and therefore risk a wage/price spiral or simply companies taking advantage of the environment to boost profits? This morning’s Bank of England inflation expectations survey showed expectations for inflation over the next year jumping to 4.3%, well above the Bank of England’s 1%-3% target range.

This is the tough balancing act that they will have to confront. Given the risks from the fighting in Ukraine, I expect that they will come out on the dovish side. I would expect fewer votes for a 50 bps hike than before. That might lower the odds of a 50 bps hike at the next two meetings, which would be negative for the pound.

Bank of Japan: getting interesting

The BoJ has the dubious distinction of being the least interesting of the major central banks, as determined by the Bloomberg relevance score (what percent of the people who have alerts programmed in for announcements from that country have an alert set for that announcement). The BoJ’s announcement gets a substantially lower rating than even the Swiss National Bank, which hasn’t changed its policy rate since 2015.

However, I think the BoJ is likely to start getting interesting. Come April, the impact of the reduction in mobile phone rates will fall out of the year-on-year comparison and the inflation rate is likely to jump, maybe to 1.5% yoy or even the Holy Grail of 2% yoy.

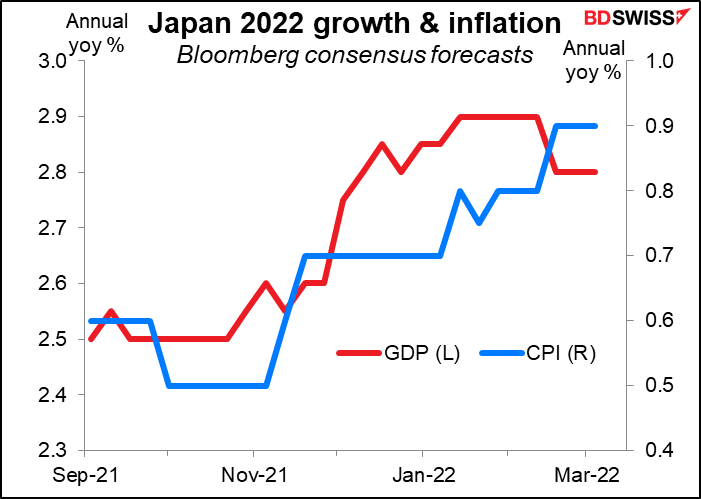

Japan is one of the few countries where the market has been revising up its expectations for growth, not down. Even so, the expectations for inflation remain well below the 2% target. (This reminds me of a funny story: years ago when I was making a presentation to a client in Japanese, I suddenly realized I didn’t know the term for “upward revision” in Japanese because for so many years I had only had to say “downward revision.”)

The BoJ won’t release an updated Outlook Report at this meeting so we won’t know for sure what the authorities are thinking, but Gov. Kuroda is likely to discuss the issue in his press conference following the meeting. He’s likely to allude to the possibility of a downturn in growth due to the war, as other central bankers have, due to greater uncertainty, lower investment, and higher prices acting as a tax on consumers. There’s some debate about the impact of higher oil prices on the Japanese economy – the Bank of Japan’s model of the Japanese economy finds that a 10% increase in the oil price leads to a 0.2% decline in real GDP, while other research finds “the effects of oil price increases in Japan are either negligibly negative or even positive.”

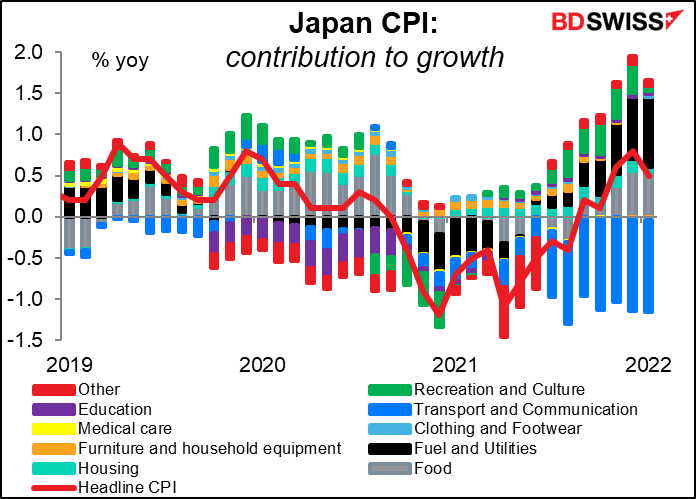

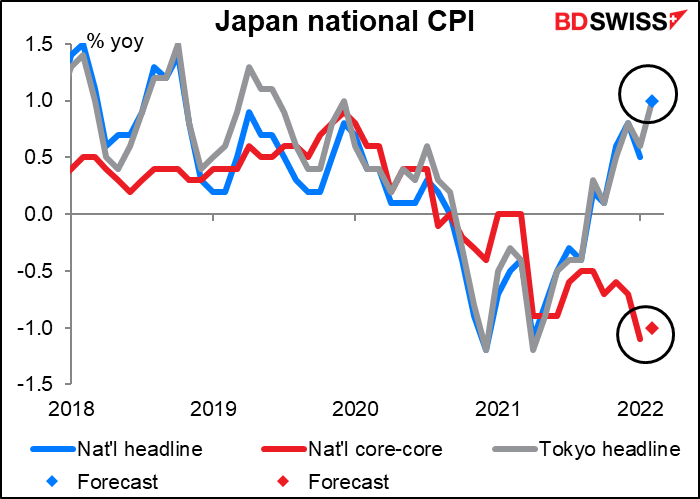

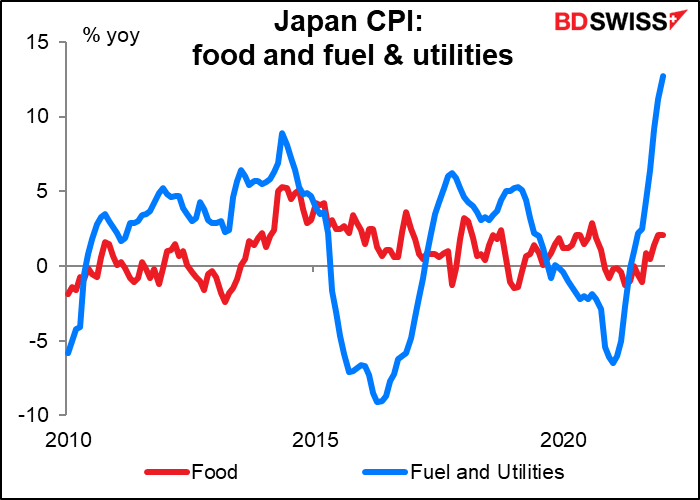

The main question for me is whether Gov. Kuroda will stick to his view that inflation won’t hit 2%. He dismissed the possibility in his press conference in January, but that was before the invasion and the surge in commodity prices. It also ignored the basic arithmetic of Japan’s cut in mobile phone charges, which are subtracting around 1.5 percentage points from the headline inflation rate. Once that drops out of the equation, inflation “may momentarily rise to a level close to 2%,” as Policy Board member Junko Nakagawa said recently. (Note the bright blue bars in the graph below.)

Japan’s national CPI will come out on Friday morning, a few hours before the BoJ meeting finishes. The headline number is expected to rise sharply to 1.0% yoy from +0.5%. That would be the same as the Tokyo CPI for the month and so would be no big surprise. The “core-core” CPI however – excluding fresh foods and energy – is expected to remain in deflation at -1.0% yoy vs -1.1% yoy the previous month. Gov. Kuroda can cite that as evidence that the impact of higher energy prices won’t be enough to push Japan over the line.

Nonetheless, the BoJ, like the Fed, may also be feeling some political pressure over inflation even if it hasn’t yet met its formal 2% inflation target. Officials have recently been referring to “people’s perception of inflation,” which is often different from the actual figure – people notice prices that are going up much more than they notice prices that are remaining stable. Gov. Kuroda told the Upper House Budget Committee recently that the BoJ would monitor a wide range of data on inflation beyond the indicators, including surveys on how the public feels about prices. As part of that effort, the BoJ released a working paper entitled “Households’ Perceived Inflation and CPI Inflation: the Case of Japan”. The paper explains “why perceived inflation is higher than CPI inflation.” Without getting into the details, I’ll just note that food prices are rising 2.1% yoy (including 6.5% yoy for fresh food) and fuel and utilities are up 12.7% yoy, including 15.9% for electricity. Ouch! No wonder my daughter in Kyoto keeps asking for more money.

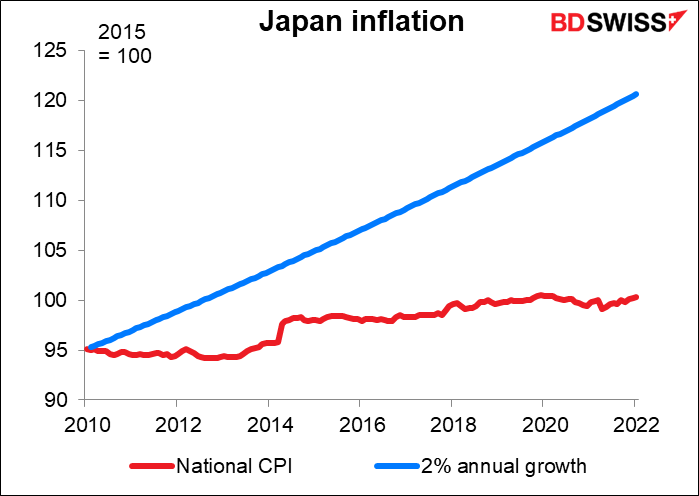

I doubt if the BoJ would raise rates any time soon even if inflation did poke its nose over the 2% line. Inflation has been so far below the 2% target for so long that they can probably tolerate an overshoot for some time. Prices are about 20% below where they would be if they had been rising at a steady 2% a year since the current consumer price index began in 2010.

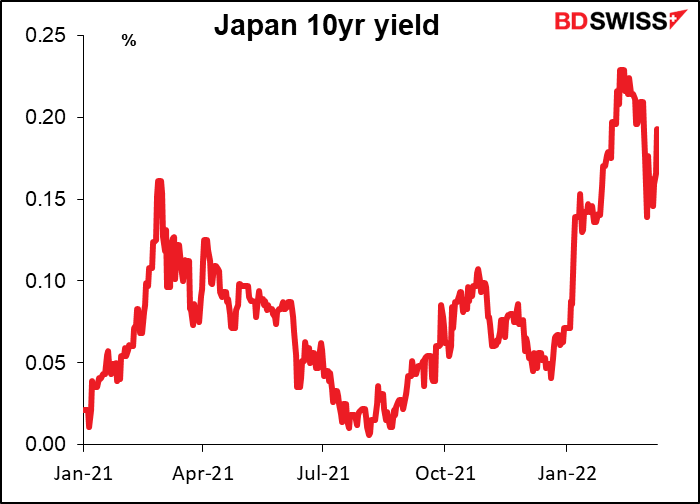

Nonetheless the BoJ could eventually relax their yield curve control (YCC), under which they pledge to keep the 10-year bond yield at around 0%, ±25 bps. The BoJ bought bonds on Feb. 14th to enforce this restriction but was unable to hold down yields in other maturities. Assuming that energy and food prices remain elevated, other central banks continue to hike rates, and that bond yields abroad behave as one might expect under such conditions, the BoJ could be forced to relax its yield curve control well before it contemplates hiking rates (as Australia did).

Until they do this, investing in JPY assets is likely to become less and less attractive for both domestic and foreign investors and JPY is likely to decline, assuming of course that there isn’t a “safe haven” bid, which of course there is now.

Other indicators: US retail sales, UK employment data, Japan & Canada CPI

There’s a lot of other information on the schedule for next week too.

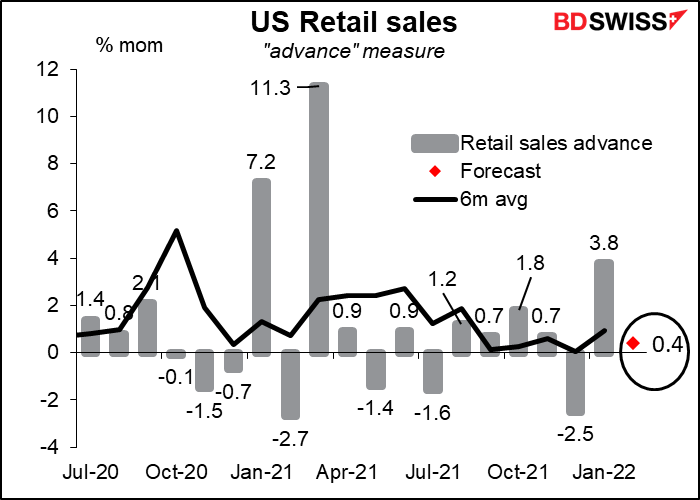

US retail sales comes out the same day as the FOMC meeting ends. That may dampen interest in what’s usually one of the more important indicators every month, seeing as so much of the US economy — some 70% — is private consumption, of which retail sales comprise some 40%. That means retail sales account for approximately 28% of the US economy.

Sales are expected to be sluggish – up only +0.4% mom compared with the six-month moving average of +1.0 mom. Part of that is due to a 5.2% mom fall in auto sales and part probably just a reaction to the exceptional sales in the previous month. Excluding autos, sales are expected to be up a more robust +0.8% mom – about in line with the average (+0.9%). The continued healthy increases in sales show that the rise in employment and in working hours is supporting total spending power.

There may also be a bit of smoke-and-mirrors in the figures in that they’re not adjusted for inflation. With prices rising at about +0.6% mom, that means even if the volume of goods sold doesn’t increase at all, the value will rise +0.6%. Looked at that way, a +0.4% mom increase in the value of sales is a decline in real terms.

I doubt if the markets will look at things that way though. I’d expect yet another rise in sales following the previous month’s extraordinary rise to be taken as good news for the US economy and therefore be positive for the dollar.

Other major US indicators coming out during the week include the producer price index (PPI) and Empire State manufacturing survey (Tuesday) and Philadelphia Fed business survey and housing starts (Thursday).

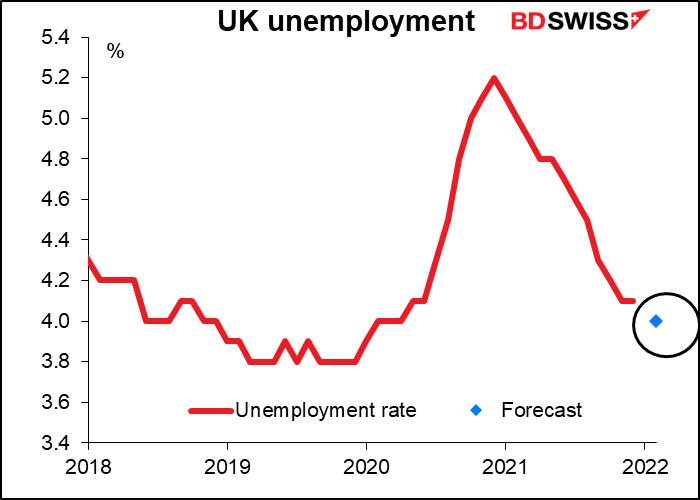

For Britain, the big thing aside from the BoE meeting will be the employment data on Tuesday. The unemployment rate is expected to fall further.

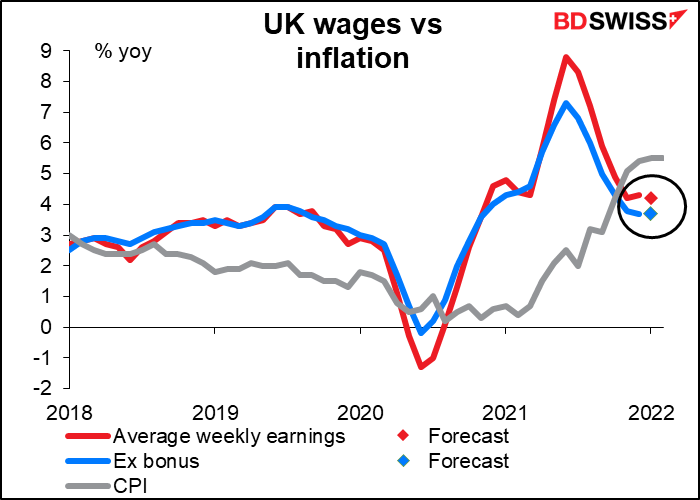

Average earnings including bonuses are expected to be down 0.10 bps and well below the rate of inflation, which should warm the icy cold hearts of those Bank of England officials who have called for “wage restraint” while they make six-digit salaries. That would tend to be slightly negative for the pound as it means less pressure to tighten but I think the falling inflation rate is probably more important.

Canada releases its CPI on Wednesday, the last inflation number before the mid-April Bank of Canada meeting. No forecasts are yet available. At its last meeting a few weeks ago, the Governing Council said it “expects interest rates will need to rise further.” A further rise in inflation, as seems likely, would only confirm that expectation.

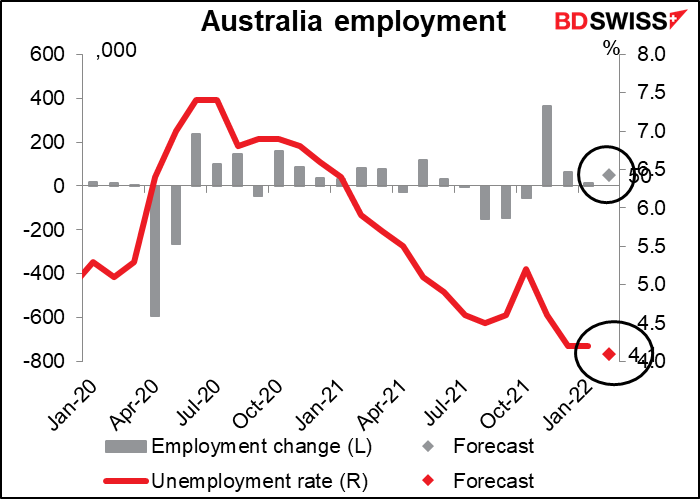

Australia releases its employment data on Thursday. It’s expected to be good – unemployment rate down, employment up more than in the previous month, and the participation rate (not shown) 0.2 point higher. Reserve Bank of Australia Gov. Lowe this week conceded that “it’s plausible that interest rates will increase this year,” but he also said there were plausible scenarios where rates didn’t rise until next year. He’s focusing on wages and the development of a wage/price spiral. In that respect, an improvement in the employment picture is positive for AUD, albeit indirectly.