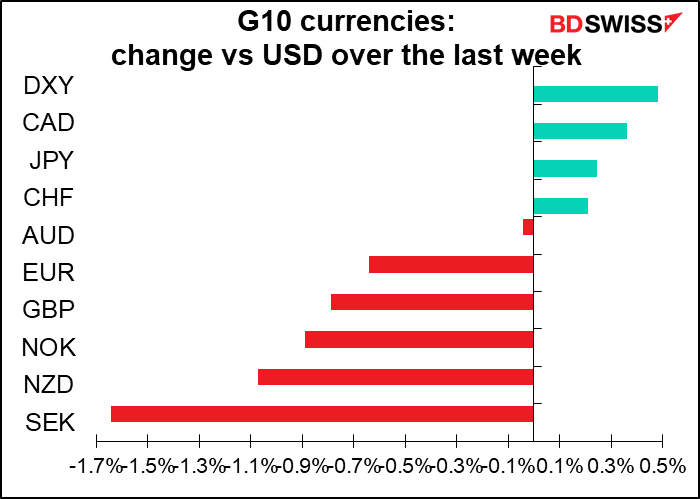

Investors are finally starting to realize that after years of zero interest rates, quantitative easing, and monetary policy convergence, it’s time to go back to normal. There are two central bank meetings next week and three more the week after. The question the market will be asking is how far and how fast they’re likely to hike rates.

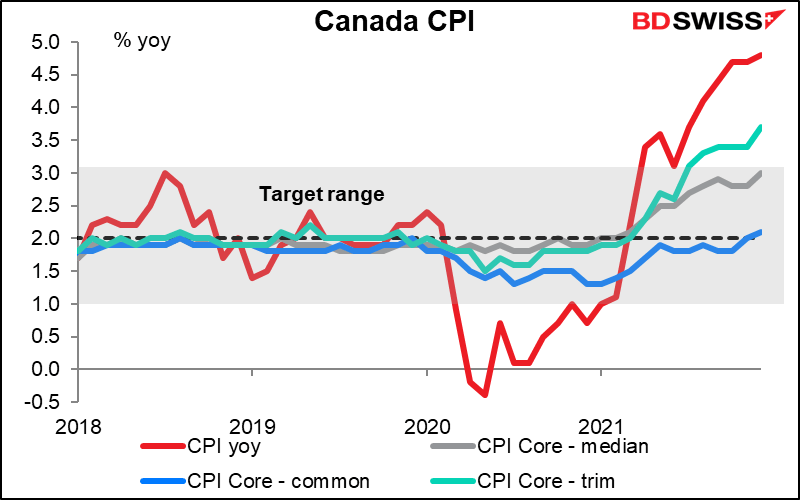

Over the last week there were several inflation readings that made “transitory” look oh-so-much like last year’s word. Canada’s headline inflation rate hit the highest level since 1991. What’s particularly worrisome is not just the rise in headline inflation but also the rise in core inflation. One of their core measures of (core-trim) is well outside their 1%-3% target range, and core-median is right at the line at 3.0%.

Similarly with UK consumer price index (CPI). At least this was no surprise; the Bank of England has already said it expects inflation to peak at “around 6%” in April.

Inflation is at or near a 30-year high in a number of major countries.

Accordingly, it’s clear that central banks are starting to lose patience. With perhaps the exception of the European Central Bank (ECB), most of them have given up on the idea that inflation will naturally fall back by itself. They’re bracing for action, with the biggest of them all, the US Federal Reserve, being among the most vocal.

Accordingly, policy expectations rose sharply over the latest week.

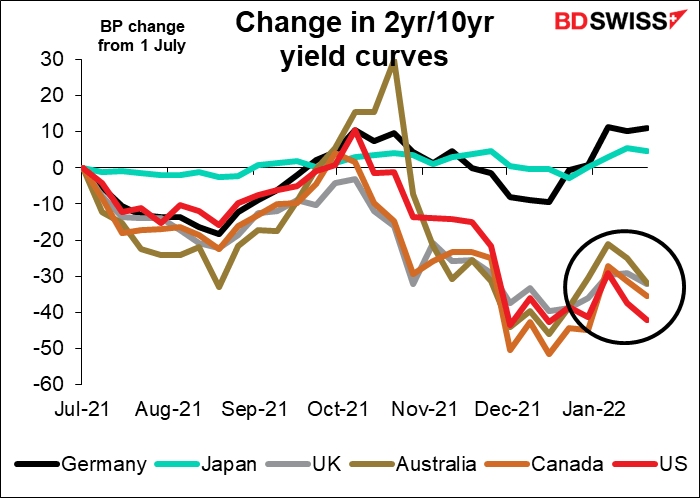

With that, bond yields moved higher around the world. What’s dangerous though is that yield curves in many countries began flattening, i.e. short rates rose more than long rates. Yield curves had been steepening since late December but began flattening late this week. That’s a sign that investors believe central banks may have to tighten so much that they send their economies into recession.

In the US for example, every US recession in recent years has been preceded by an inversion of the US 2yr/10yr yield curve. The 2yr/10yr curve is currently 76 bps, half the level of March last year.

Against this background, Wednesday’s meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will be the pace-setter.

The Fed is clearly planning on tightening policy this year. In December the “dot plot” showed that the median FOMC member expects three rate hikes this year, a huge change from the September forecast of zero. Moreover, the Committee doubled the pace of tapering down its bond purchases so as to finish by March, a clear sign that it wants to start hiking rates ASAP. (It has said previously that it wouldn’t start hiking rates until it had ended its bond purchases.)

On the other hand, it hasn’t made any decisions yet about how soon after it ended its bond purchases it would start hiking rates (“lift-off”), nor did it decide how long after it started walking rates it would start shrinking its balance sheet – “quantitative tightening,” or QT. There’s also the question of how quickly it would start shrinking its balance sheet – how much it would allow the balance sheet to shrink every month. (At first it will shrink the balance sheet naturally as bonds mature, but if it wants to limit the pace of decline it could reinvest the proceeds of maturing bonds over a certain limit.)

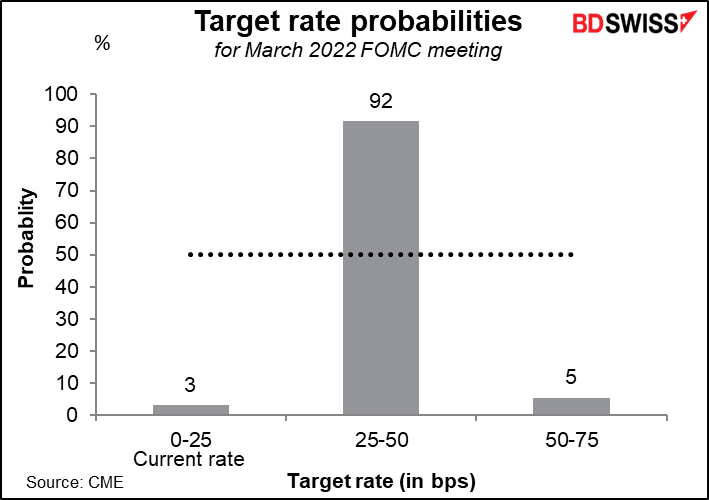

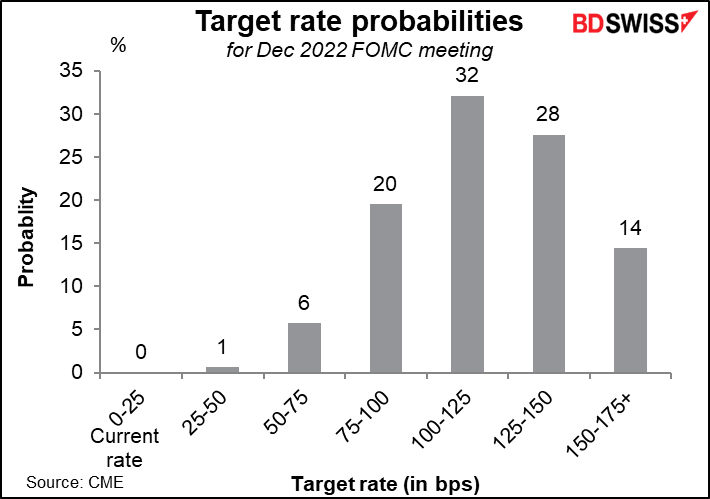

I don’t think anyone seriously expects the Fed to change rates at Wednesday’s meeting. Right now, that’s assumed to start in March.

Investors then expect four or possibly five (or more!) hikes total during the year, in contrast to the three that the Committee members predicted just last month.

Instead, the market will be looking for answers to the above questions, namely:

I don’t expect any answers to these questions this month. Why would they pre-announce what they’re going to do and give away their option to stand pat if something unforeseen happens?

However, I think they’re likely to tinker with the statement to signal an impending hike. For example, in May 2004 they said “At this juncture, with inflation low and resource use slack, the Committee believes that policy accommodation can be removed at a pace that is likely to be measured.” They then started hiking rates in June. (There was no such hint ahead of their rate hike in December 2016.) In September last year they said, “If progress continues broadly as expected, the Committee judges that a moderation in the pace of asset purchases may soon be warranted.” They then began tapering down their bond purchases at the next meeting. This time, they might replace the sentence “The Committee would be prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge…” with something like “if labor market progress continues broadly as expected, the Committee judges that an increase in the federal funds rate may soon be warranted.” I wouldn’t expect them to use the word “measured” this time, as that was taken to indicate a steady, regular series of rate hikes.

I think rather than the statement, the focus will be on Fed Chair Powell’s press conference afterward, when we can expect him to be deluged by questions on these matters. He’s not likely to commit to anything though, instead preferring to keep maximum flexibility by stressing that each meeting is “live,” meaning that they’ll cross each bridge when they come to it rather than pre-committing to any particular pace of tightening.

What are the risks: As shown above, the market is anticipating that the Fed will continue to turn hawkish. It would be hard to see them out-hawking the market at this point and somehow signaling that yes, five rate hikes is reasonable, six possible. On the contrary, they could push back on market pricing and try to lower market rate expectations. Doing so might simply raise fears that they’re “behind the curve” and not willing to take the steps necessary to fight inflation. It might cause long rates to rise as investors anticipate higher inflation in the future. Or it could cause the yield curve to flatten more as investors anticipate that eventually the Fed will have to hike rates even higher to make up for this mistake. On the other hand, a more dovish-than-expected Fed would probably prove popular with the stock market.

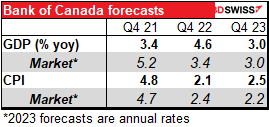

A few hours before the FOMC meeting winds up, the Bank of Canada will hold its policy meeting and release an updated Monetary Policy Report. At their last meeting on Dec. 8th, they said they expected to start hiking rates “sometime in the middle quarters of 2022.” The market doesn’t believe a word of it. It’s pricing in a 73% chance of a hike at next week’s meeting and another hike at the March meeting.

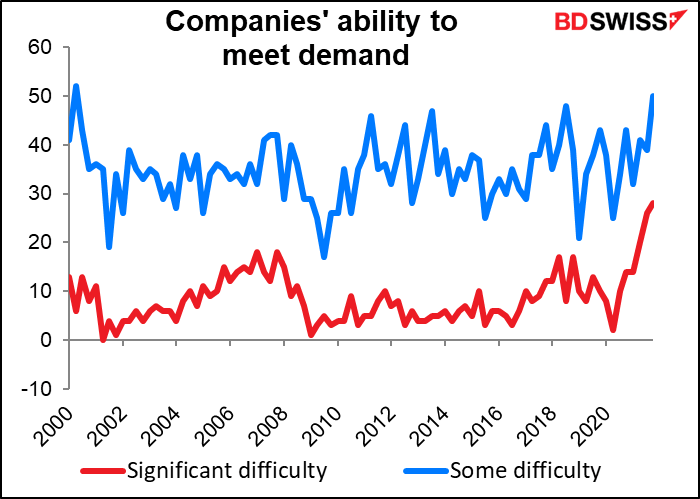

The reason the Bank said it won’t be able to hike rates until the middle of the year is because “of ongoing excess capacity….” They have to hold policy unchanged “until economic slack is absorbed…” But I wonder if the December Bank of Canada Business Conditions survey may have changed their view. The diffusion index for companies encountering “significant difficulty” in meeting demand hit a record 28, while those encountering “some difficulty” hit a near-record 50, meaning that at least half the companies are encountering such problems.

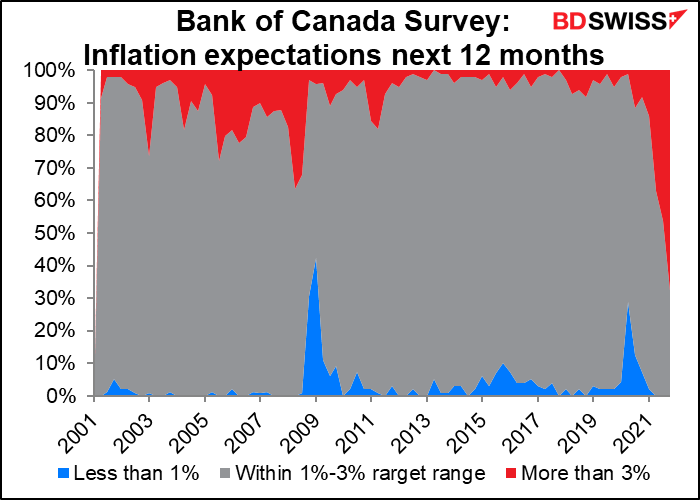

Meanwhile, a stunning 67% of respondents expect the inflation rate to be outside the Bank of Canada’s 1%-3% target range over the next 12 months.

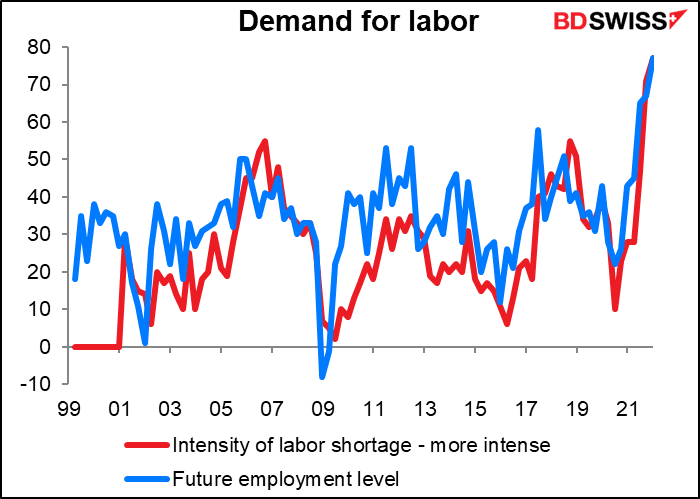

And demand for labor is at far and away the highest level it’s been since the survey started over 20 years ago.

The Bank said it “is closely watching inflation expectations and labour costs to ensure that the forces pushing up prices do not become embedded in ongoing inflation.” Viewing the results of the BoC Survey against that statement, it would seem that they’d better do something très rapidement, eh?

The key may be if they revise up their 2022 inflation forecast in the accompanying Monetary Policy Report.

In short, the market is looking for a hike in Bank of Canada rates and some guidance on how quickly the Bank will tighten. Will there in fact be six rate hikes this year as the market is currently discounting?

Also, the BoC faces the same problem as the Fed in terms of its balance sheet—worse in fact, since the BoC increased its balance sheet far more (4.2x vs 2.1x).

According to my sources in Toronto, nothing official has been said but pressure is building from all sides. Many market participants are calling for them to reduce the balance sheet as the Bank is sitting on 46% of the total outstanding stock of Canadian government bonds. The October Monetary Policy Report just says

Looking ahead, a significant amount of bond holdings will mature in the coming years, concentrated in the next one to five years, and these maturities will vary month to month. Given this combination of large and uneven maturities, the Bank’s total holdings of GoC bonds will fluctuate modestly over the next few years.

It’s not clear to me from this whether they intend to let the balance sheet fall back to where it was before the pandemic or whether they’ll try to maintain it somewhere around its current size (relatively enormous compared to the past).

Overall, these two central bank meetings will set the stage for the following week’s meetings of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Bank of England, and the European Central Bank (ECB).

Other indicators: Preliminary PMIs, US & Germany Q4 GDP, PCE deflators, AU, NZ and Tokyo CPIs

In addition to the two central bank meetings, there are a large number of important economic indicators coming out during the week.

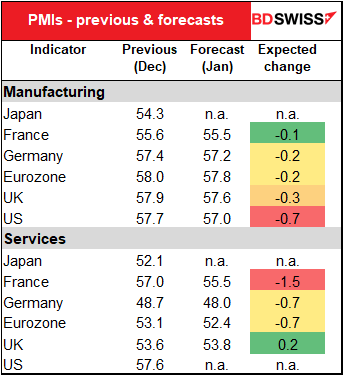

The week starts with the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major industrial economies. The markets are expecting mostly bad news; only the UK service-sector PMI is expected to be up, and that’s just +0.2. The service sector on the Continent is expected to take a hit, not surprising as both Germany and France tightened down their COVID-19 restrictions in early December. France eased them a bit a week or so ago, Germany hasn’t budged. US manufacturing is expected to be down sharply, perhaps following the disappointing Empire State manufacturing survey (which plunge to -0.7 from 31.9).

Weaker Eurozone PMIs may encourage the ECB to take a “wait-and-see” stance at its meeting on Feb. 3rd, which could be negative for EUR.

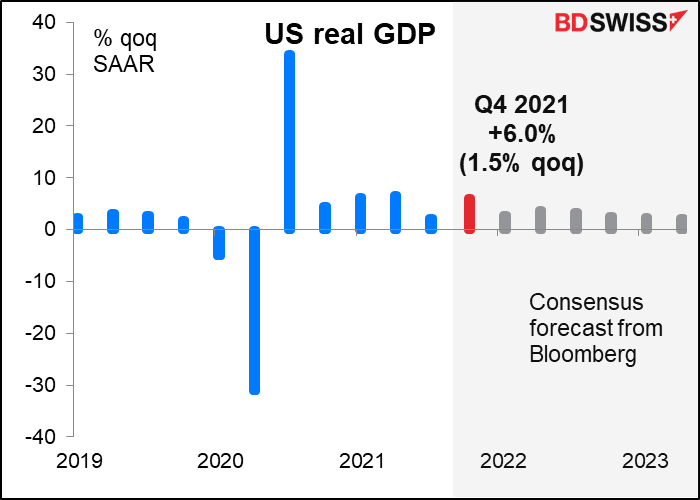

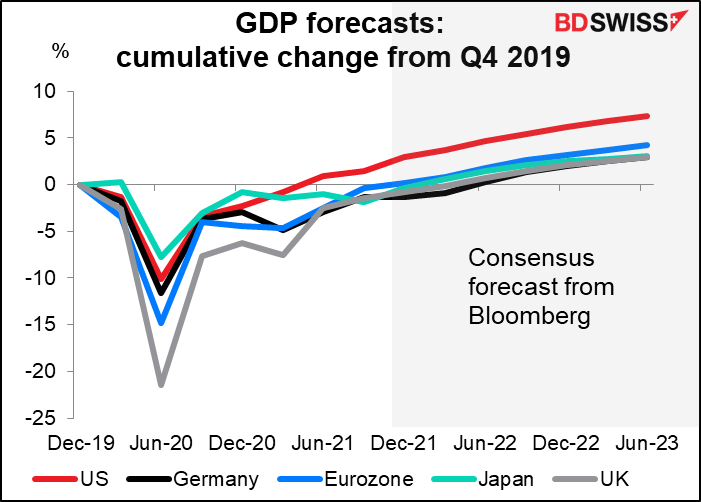

The US and German GDP figures are expected to provide a stark contrast. US GDP is forecast to rise a robust 6.0% qoq SAAR rate (+1.5% qoq)…

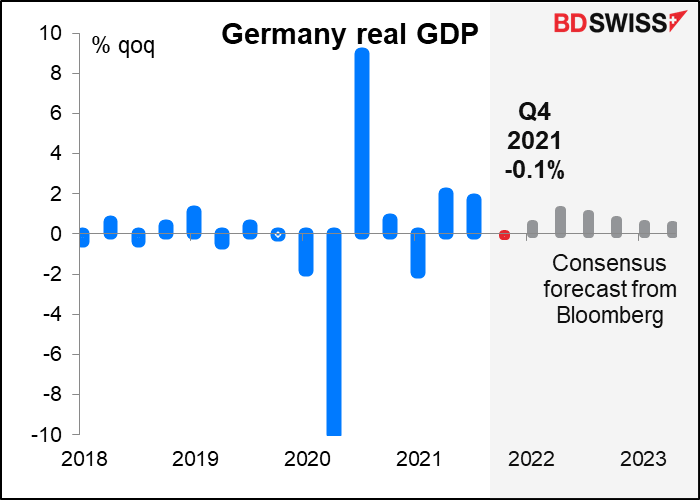

…whereas German GDP is forecast to be down 0.1% qoq.

The US has recovered far faster from the pandemic than its major competitors have. The strong growth added to the highest inflation among the G10 should mean a relatively rapid pace of tightening and therefore a strong dollar.

The inflation data from Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and the US is forecast to show further rises in inflation worldwide (except in Japan, the global outlier). This worldwide trend should further justify further tightening. The fur will be flying!

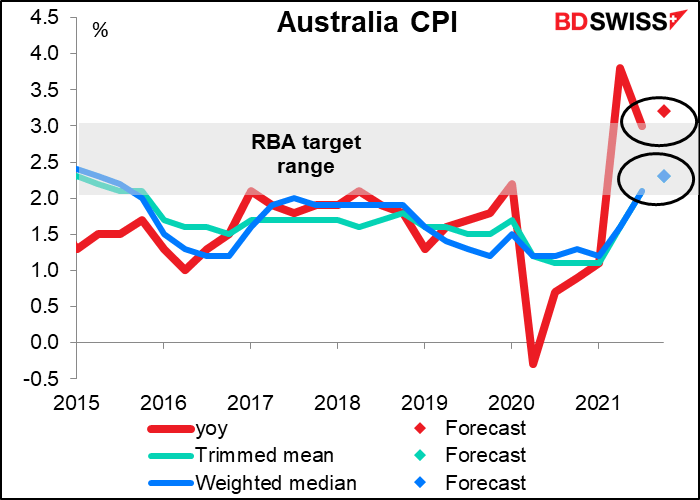

Australia’s headline CPI is expected to be up slightly to 3.2%, still outside the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)s 2%-3% target rand. The two core measures meanwhile are forecast to be squarely within the range (both at 2.3% yoy). (The inflation target in Australia is defined by headline inflation; the core measures are used “in assessing current inflation pressures and the outlook for CPI inflation.”)

Inflation above target, unemployment below the level it was before the pandemic began, and employment higher; how long will the RBA be able to argue that it’s “likely to take some time” before inflation is “sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range”? AUD+

New Zealand’s CPI is expected to move sharply higher (5.8% yoy vs 4.9%). This would be nearly double the upper boundary of their 1%-3% target range.

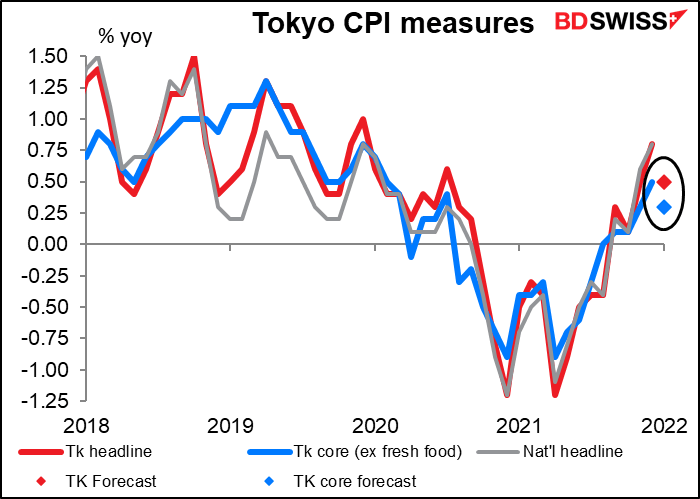

There’s been a lot of speculation recently (well, I’ve been speculating a lot recently) about how Japan’s inflation could heat up thanks to higher prices for imported raw materials, which are up 68% yoy. However, Friday’s national Japan CPI showed little sign of that – the headline CPI rose only to +0.8% yoy from +0.6%, while the “core-core” measure of inflation – excluding fresh food and energy – actually fell deeper into deflation (-0.7% yoy vs -0.6%).

I should note though that Japan’s inflation rate is being held down by government programs that have depressed prices for accommodations and mobile phone charges. The government’s “Go To Travel” campaign, which subsidized hotel fees during the pandemic, lowered accommodation rates in August-December 2020. That pushed up inflation on a yoy basis a year later. As this effect drops out, it conversely lowers the inflation rate a year after that (i.e., starting from next week’s January 2022 figure). Meanwhile, the government pressured mobile phone companies into cutting their charges in April last year; the yoy effect will drop out of the calculation in April this year. Economists have estimated that without these two factors, core inflation would be about 1.6% yoy. That’s probably a more accurate estimate of the actual inflationary pressure. It’s still far lower than in most other countries, but it’s not deflation.

Be that as it may, the published figures do include hotels and mobile phone charges. Accordingly, the expectations for next Friday’s Tokyo CPI are pretty meager. All measures are expected to show a lower rate of inflation than in the previous month, with the “core-core” (not shown) particularly expected to fall to -0.7% yoy from -0.3%. I guess we can put aside thoughts of Bank of Japan startling to normalize policy any time soon. The picture may change once the decline in mobile phone charges drops out of the year-on-year comparison, though.

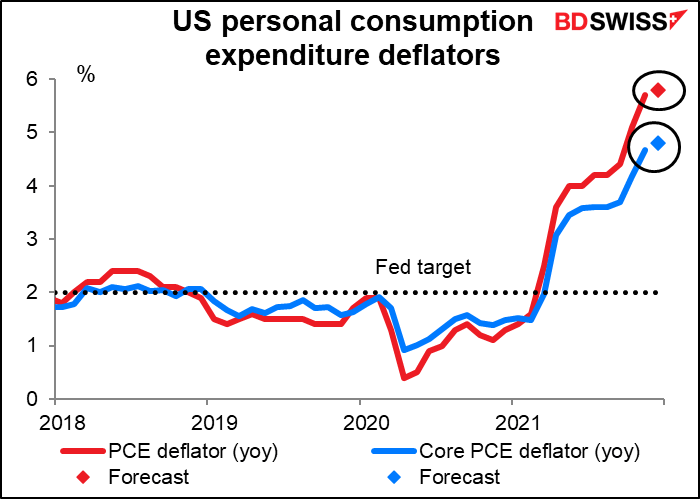

Finally, the US personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators are out on Friday. These, and not the more widely known consumer price index, are the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. They made the switch back in 2000. Nonetheless, the market still pays more attention to the CPI and I’ve been surprised to hear some Fed officials refer to the CPI as well, even though the Fed prepares all of its forecasts in terms of the PCE deflators, not the CPI.

In any case, the story we get from the PCE deflators is expected to be the same as the story we got from the CPI: higher inflation. Investors may take some solace from the fact that the pace of increase is expected to slow, but as long as the direction is up, the Fed is going to be in no mood to take their foot off the brakes.

Other US data out during the week includes Conference Board consumer confidence (Tuesday), durable goods (Thursday), and personal income & spending (Friday).