We’ve heard from a number of central banks recently. In fact, we’ve been hearing from central banks almost constantly, in unscheduled meetings as well as scheduled. But this week there were meetings of four major central banks: the Bank of Japan, the Fed, the ECB and Sweden’s Riksbank, which I don’t usually cover. I’d like to pick up a few points from those meetings that attracted my attention.

There was one point in the Riksbank’s Monetary Policy Report that laid out quite clearly and formally something that Fed Chair Powell described informally in his press conference: the three phases of recovery.

- In the first phase, which most countries are currently in, there’s lockdown. The economy is cratering. During this period, central banks are all in. According to the Riksbank, “economic policy needs to concentrate entirely on giving as much support as possible to households and companies to help them get through the crisis.” As Powell put it, “This is the time to use the great fiscal power of the United States to do what we can to support the economy..”

- The second phase, which China is going through and a few others – such as New Zealand and Austria – are starting to enter is the period when restrictions are gradually relaxed. People will start to come out of their houses and the economy will gradually recover, but some industries may take longer than others as people remain cautious. “The economic policy measures to bridge over the crisis are gradually withdrawn, or change towards more general stimulation of demand, as society starts to open up,” the Riksbank said. Powell said that for discussion’s sake this might be Q3 in the US, although he was not making a formal forecast.

- The third phase starts when the pandemic is over – presumably when there’s a vaccine or “herd immunity” has been reached. During this time, the authorities will aim at reducing support and gradually normalizing policy. However, the process will inevitably be slow. “The negative consequences of the crisis will probably cast a shadow over economic developments for a long time, for example via significantly higher sovereign debt in most countries, highly indebted companies, high unemployment and substantial pressure on structural transformation in the economy,” the Riksbank said. Powell discussed at length the possibility that the crisis could inflict long-term “damage to the productive capacity of the economy” by disrupting careers and destroying businesses.

What does this mean for policy? It means that central banking as we know it is out the window for the foreseeable future – and the future isn’t very foreseeable. As Dr. Fauci, the director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, famously said, “You don’t make the timeline, the virus makes the timeline.” Or as Powell put it, “what the experts tell us is that the outcomes are highly uncertain. So, this is an unusually new kind of uncertainty added on top of our regular uncertainty.” The length of these periods depends more on medical developments than on economic developments. That means the path of monetary policy will also be determined by the virus.

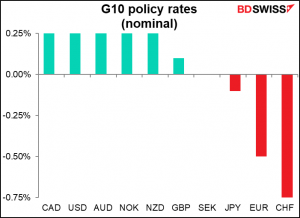

For most of my career, central bank policy has meant interest rate policy. Even the “zero bound” seemed to be no longer a binding constraint as the ECB and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) experimented with negative rates. But those experiments seem not to have worked well and are not being pursued by other central banks. It seems that interest rates are largely frozen from now. The Fed, the Bank of Canada and the Reserve Bank of Australia all specifically referred to their rates as being at “the zero bound.” The Reserve Bank of New Zealand said that should further stimulus be required, it would prefer quantitative easing to further reductions in its Official Cash Rate. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) talks about FX market intervention, but not about cutting rates further. And following this week’s ECB meeting, interest rates weren’t discussed until the 12th paragraph. As recently as January, the President usually addressed rates in Paragraph #2, right after “the Vice-President and I are very pleased to welcome you to our press conference.” While the Bank of Japan, like the ECB, says that it expects rates “to remain at their present or lower levels,” they have passed up numerous chances to reduce their policy rate further, preferring instead either to increase the size of their current purchases or to create new lending facilities.

On the other hand, the Bank of England did not refer to any limits on reducing rates further as it cut its Bank Rate to a record low 0.10%. Norges Bank, which is at 0.25%, said it “does not rule out that the policy rate may be reduced further,” without saying how much further. And Sweden’s Riksbank specifically mentioned its willingness to cut the repo rate from its current level of 0%.

If the price of money is no longer their main tool, then all they have left, as Japan discovered a long time ago, is the quantity of money. More or less they have all turned to quantitative easing and yield curve control, the Bank of Japan’s familiar tools. Central banks have gone back to their original role of financing the government.

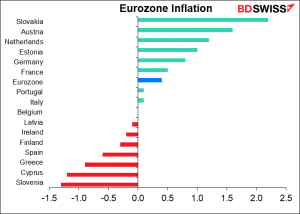

They can justify this change within the context of their mandates because restraining inflation is no longer a problem. On the contrary, the “Japanification” of the global economy continues as inflation expectations, already well below the general 2% target, fell further with the advent of the crisis. Thus if they interpret their mandate for stable prices to be symmetrical – as they all do – then acting to boost the economy at this juncture is required anyway to get inflation back to target.

Indeed, several European countries are already seeing deflation. Most of them are smaller nations, but also Spain, the fourth-largest EU economy. Italy is almost there. Only two Eurozone countries meet or exceed the ECB’s target.

And this week’s Bank of Japan quarterly “Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices” report quietly dropped inflation as a policy target at all.

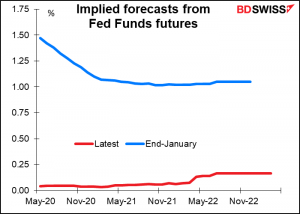

My conclusion from this – which I set out a few weeks ago in Looking for New Market Drivers – is that economic indicators are no longer likely to be a major source of market movement. That’s because the central banks’ reaction functions have effectively been turned off. They are not going to adjust interest rates in response to economic conditions, they are only going to adjust debt purchases in response to government funding programs. Several have promised to keep rates unchanged at least until the end of the year, most until their economies are well on their way to being healed, however long that might be. Powell noted that “if you look at market pricing, the market expects us to be (at the zero bound) for a good while, and that’s appropriate.” Fed fund futures go out to March 2023 and they’re not discounting a full return to a 25 bps Fed funds rate even by then. As recently as January they were predicting 1.0%.

We’ve seen this phenomenon in action this month. Who could have imagined that in a month when 20mn people lost their jobs, personal spending fell the most on record, and various business sentiment indices fell to record lows…that the stock market would have its best month since 1987 (almost since 1974)? The economic statistics aren’t moving markets; virus news is. That’s likely to continue for some time.

This week’s events: RBA, BoE, NFP. ENUF?

After this week’s busy schedule, next week has much fewer stand-out events.

The week starts with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) meeting Tuesday. I expect little out of this except a reaffirmation of their existing policy.

On the one hand, the Reserve Bank Board’s members think the Cash Rate is “now at its effective lower bound” and that they have “no appetite for negative rates.”

On the other hand, it’s likely to be “a couple of years” before they start raising rates. RBA Gov. Lowe recently said he expects the unemployment rate to “remain above 6% over the next couple of years” and headline inflation go negative in Q2 and “to remain below 2% over the next couple of years.” (See his speech from 21 April, An Economic and Financial Update.) Meanwhile, the RBA has repeatedly pledged not to increase rates “until progress is being made towards full employment and it is confident that inflation will be sustainably within the 2–3 per cent target band.” (They estimate full employment to be around 4 ¾% unemployment.) In other words, no rise in rates is likely for “the next couple of years.”

The RBA was the second-most aggressive central bank in responding to the crisis in terms of growing its balance sheet, even more so than the Fed. (The Bank of Canada was #1. I don’t even include it on the graph because it was more than double the others and distorts the scale.)

If the RBA felt the need to take any more action, it would probably increase the size of its purchases of government bonds. However, at this point it’s satisfied with what it’s doing – it’s even started reducing its balance sheet a little. Gov. Lowe explained, “As conditions in the market have improved and the 3-year yield has settled around 25 basis points, we have scaled back our daily bond purchases…We will scale up these purchases again if needed and we will buy bonds in whatever quantity is required to achieve our goals.”

The RBA’s success in stabilizing its domestic financial system can be seen in the LIBOR-OIS spread (or in the case of Australia, the 3m bank bill-OIS spread). (OIS stands for “overnight index swap,” a rate based on the central bank’s lending rate.) This spread in AUD was about the same as in USD and higher than EUR before the crisis. Now it’s lower than both – in fact, it’s about zero, indicating that banks have no problems getting funds at all.

In short, I would expect the RBA simply to reiterate that its policies are currently working but if they prove insufficient in the future, it stands ready to do “whatever is necessary.” I don’t expect the meeting to have much effect on AUD.

The RBA’s Statement on Monetary Policy comes out on Friday. This usually contains the RBA’s forecasts. However, I fail to see how anyone can make any forecasts in today’s environment. Gov. Lowe said in his recent speech (referenced above) that “Economic forecasting is difficult at the best of times. It is even harder at times like this when we are experiencing a once in a lifetime event. Given this, I don’t think it makes sense at the moment to focus on forecasts to the nearest decimal point, as we often do.” Perhaps they will follow the lead of the IMF in its recent “World Economic Outlook” and publish a fairly optimistic central scenario that assumes everything goes well and the lockdown is lifted soon, along with more pessimistic (some might say “more realistic”) scenarios, such as a longer lockdown or a “second wave” later in the year. The market could react to the forecasts, but then again, I’m not sure anyone believes any forecasts now.

Bank of England

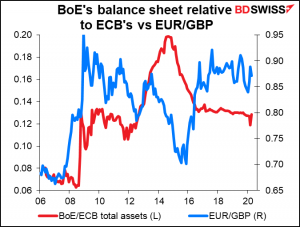

As the first graph above shows, The Bank of England has been much less aggressive in terms of expanding its balance sheet than the Fed (but about the same as the ECB). That doesn’t mean it’s been inactive: it held three meetings in one month, vs the usual eight per year, cutting rates by 65 bps to a record low and in conjunction with the Treasury, introduced several programs to provide money to companies. I think the BoE could decide at next week’s meeting to increase its bond purchases further, to get financial conditions under control and to help fund the government’s rising issuance.

At its special meeting on 19 March, the BoE cut Bank Rate by a further 15 bps to a record-low 10 bps and announced a quantitative easing program of GBP 200bn. It explained the moves as follows:

Over recent days, and in common with a number of other advanced economy bond markets, conditions in the UK gilt market have deteriorated as investors have sought shorter-dated instruments that are closer substitutes for highly liquid central bank reserves. As a consequence, UK and global financial conditions have tightened.

At its special meeting on 19 March, the MPC judged that a further package of measures was warranted to meet its statutory objectives. It therefore voted unanimously to increase the Bank of England’s holdings of UK government bonds and sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bonds by £200 billion…and to reduce Bank Rate by 15 basis points to 0.1%.

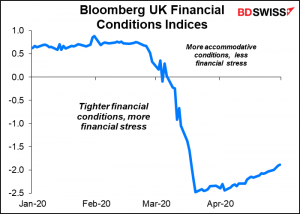

But as the second graph above shows, financial conditions haven’t recovered. The LIBOR-OIS spread, which was at 52 bps on 19 March, is currently at 57. And the Bloomberg UK financial conditions index, which was in “loose” territory before the virus hit, has barely rebounded off its low – although it’s still nowhere near what it was back in 2008.

Meanwhile, the UK Debt Management Office (DMO) Wednesday detailed its plans to issue GBP 180bn in gilts in the next three months. Given that the BoE has already bought GBP 80bn, that will exceed the Bank’s planned purchases for its Asset Purchase Facility (APF). They do have meetings scheduled for May and June, so they could increase the size of their purchases then without running up against the limit. But why wait when it’s inevitable? Especially because a move like that would be more natural at a meeting that included a new set of forecasts, and that would be the August meeting, by which time it would be too late.

The Bank of England – like most other central banks – is being driven by fiscal policy, not monetary policy. It’s effectively acting as the Treasury’s banker, writing blank checks to pay for fiscal policy. It can justify its actions with reference to its mandate, which in the case of the BoE is “to maintain price stability, and subject to that, to support the economic policy of Her Majesty’s Government, including its objectives for growth and employment.” Since inflation is likely to fall dramatically (as mentioned above, the RBA sees deflation in Q2), there’s currently no contradiction between maintaining price stability and supporting growth and employment. So the BoE – and other central banks too – are free to keep printing all the money they want.

Other possible actions: the BoE could also do some fine-tuning of its other policies, such as adjusting the eligibility criteria for the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS) to include “fallen angels,” bonds that were investment grade before the virus struck but have since been downgraded (a move several other central banks have taken). It could similarly ease collateral requirements.

Market response: the relative size of balance sheets doesn’t seem to be a driver of either GBP/USD or EUR/GBP. Therefore, another GBP 100bn or so of gilt purchases shouldn’t have a major impact on the FX market.

Rather, the key will probably be on what they say. If instead of expanding purchases by GBP 100bn they say something like “buy as much as needed,” then we could see some temporary weakness in GBP, although since everyone else is buying as much as they can too, it won’t change the relative picture long term. If they say that they are open to cutting rates to negative, then that would probably be a big deal, because they’ve opposed the idea up to now. But as I discussed above, it’s clear that interest in negative rates as a policy tool has been waning among central banks recently.

Lastly, will they make any forecasts? The quarterly Monetary Policy Report, which is scheduled to be released at this meeting, contains the Bank’s forecasts for the economy. They face the same dilemma I mentioned above with regards to the RBA’s Statement on Monetary Policy: how can they make any believable forecasts? Again, the most likely solution will be a range of forecasts. That will allow them to put forward a variety of views without seeming to endorse a negative outlook, much like they did with regards to Brexit. Again, the market could react to the forecasts, but then again, I’m not sure anyone believes any forecasts now.

Nonfarm payrolls: Get ready for a biggie.

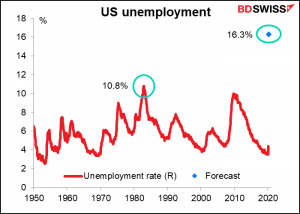

We’ve seen a lot of unprecedented statistics recently, but this one is likely to be The Mother of All Unprecedented Statistics. Nonfarm payrolls are forecast to fall by an astonishing 22mn and the unemployment rate is expected to leap to 16.3%. And these numbers aren’t the whole story. The jobless claims show that 31mn people filed for unemployment benefits in March and April, meaning that these figures wouldn’t count 8mn people who have already lost their jobs – and more will lose theirs before the May figures are calculated.

Since Oct. 2010 there were 113 consecutive months of increases in the NFP, the longest string on record, for a net increase of 22.13mn jobs. If this month’s forecast is correct, all 113 months of payroll gains will be wiped out in two months.

The average weekly earnings figure is expected to show an acceleration in earnings. Don’t be fooled! If it does, it’s only because so many lower-paid people in the service industry have lost their jobs that the average has risen.

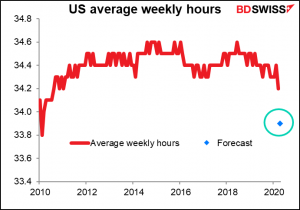

One figure that up to now only economists have paid attention to is the average weekly hours of all private-sector employees. That’s because until recently, this has been a deathly boring number –ranging between 34.3 and 34.6 since March 2011. Snore! But it’s expected to fall this month, and the implications of this are serious. Many people are paid by the hour, so if they work fewer hours, they make less money. And if they make less money, then usually they spend less money too. The rule of thumb is that one-tenth of an hour on the average workweek is equivalent to around 250k jobs in terms of aggregate income creation, according to Bloomberg economist Carl Riccadonna. So the expected fall in average hours is equivalent in spending terms to another 750k people losing their jobs – not a lot in the face of this month’s expected 22mn lost jobs, but something to watch for as the economy recovers.

Market impact: Although the data are likely to be disastrous, I don’t think the market reaction will be especially dramatic. US Q1 GDP was worse than expected, and yet stocks rallied on the day as there was some hope for a drug to treat the virus. The fact is, a) no one has any idea what the indicators are going to be nowadays; b) everyone is braced for them to be unparalleledly bad in any case; and c) there’s not likely to be any immediate change in market expectations for official policy no matter how bad they are, because governments are already planning on doing everything that they can anyway.

The US economic indicator surprise index, a measure of how economic statistics compare to economists’ estimates, recently hit -133, only a few points off the record low of -141 hit in December 2008, when really no one had a clue as to what was going on. (Data back to 2003.) A minus figure indicates that the statistics as reported are worse than expected. As Powell said, there’s “an unusually new kind of uncertainty added on top of our regular uncertainty.”