The mantra of many of the major central banks is that the current unusually high rate of inflation is just “transitory.” Here’s what a few central banks have to say:

Fed: “Inflation is elevated, largely reflecting transitory factors.”

ECB: “The current increase in inflation is expected to be largely temporary and underlying price pressures are building up only slowly.”

Bank of England: “The Committee’s central expectation continues to be that current elevated global cost pressures will prove transitory.”

Etc etc. Need I go on?

However, energy markets are threatening this rosy scenario, presenting central banks with a conundrum: do they abandon their inflation targets in order to help economies get over the unprecedented shock of the pandemic, or do they risk snuffing out the nascent recoveries in an effort to restrain inflation?

Oil naturally catches the headlines because a) everyone knows what it is and b) higher oil prices affect everyone who owns a car, which is most journalists. Certainly the 70% rise in crude oil prices this year is unusual and bound to create stresses on the global economy.

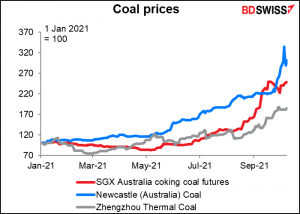

The rise in oil prices is nothing like the rise in coal, which has more than doubled (almost tripled for some Australian coal). There are still a lot of electric power stations that use coal, so higher coal prices will feed through to higher electricity prices.

But natural gas says…hold my beer! US natural gas prices are up 106% so far this year, but that’s nothing compared to Europe – UK prices are up 429% and Netherlands prices are up 432%! And those are not the peak prices of the year — closing peaked on Tuesday. These prices are the equivalent of oil trading at around $200 a barrel ($/bbl).

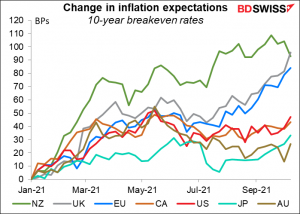

As energy costs rise, inflation expectations rise too – up 96 bps so far this year in the UK, 84 bps in the EU and 47 bps in the US.

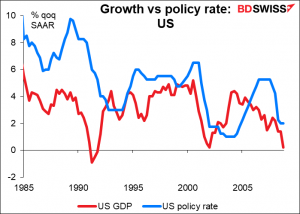

The markets assume that higher inflation will be met with higher interest rates. That’s been the reaction function of central banks ever inflation targeting became standard practice in the 1990s. But during this period, higher inflation was generally associated with higher growth. Inflation was caused by excess demand, which could be cooled by higher interest rates.

But what about now, when higher inflation is being caused by supply bottlenecks? Higher interest rates won’t suddenly create more gas wells nor container ships nor semiconductors. They may succeed in bringing demand down to the level of supply, but is it appropriate to deal with higher inflation caused by insufficient supply by making investment more expensive?

What will central banks do if higher inflation is accompanied by slower growth?

The bottom line is, we will have to wait to see how central banks respond to this unusual round of higher inflation driven by supply issues. It could well be that they stick to their “transitory” view, although the Bank of England is already beginning to waver (e.g., “global inflationary pressures have remained strong and there are some signs that cost pressures may prove more persistent.”) If they do stick to their “transitory” thesis, then we could see real rates fall and some currencies weaken – notably the dollar.

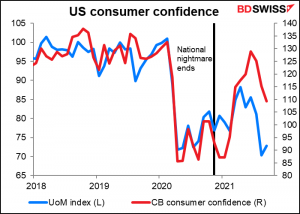

One side point I can’t resist making: I’d like to point out this paper I ran across entitled “The Economics of Walking About and Predicting US Downturns.” It argues that “consumer expectations indices from both the Conference Board and the University of Michigan predict economic downturns up to 18 months in advance in the United States…downward movements in consumer expectations in the last six months suggest the economy in the United States is entering recession now (Autumn 2021) even though employment and wage growth figures suggest otherwise.”

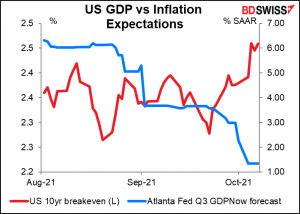

In that context, the recent downgrade of the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNowcast forecast for Q3 GDP contrasted with the upturn in US inflation expectations is worrisome. This is one reason why the US retail sales figures bear watching (see below).

Indicators for next week: US CPI, retail sales, JOLTS, and lots of UK data

There are no major central bank meetings next week and surprisingly few central bank speakers, either. There is a European Central Bank (ECB) conference Monday and Tuesday on “Monetary Policy: Bridging Science and Practice,” although I think they’re being rather optimistic to talk about “science” in the context of central banking. Looking at the agenda I don’t think there’s anything we need to worry about, although some of the papers could shed light on how central banks plan on dealing with the problem I laid out above.

The minutes of the Sep. 22nd meeting of the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on Wednesday will be a highlight, as they always are. That’s the meeting where we finally got the official word that “If progress continues broadly as expected, the Committee judges that a moderation in the pace of asset purchases may soon be warranted.” Of course the minutes are most useful in giving us insights into disagreements among the members and some feel for which way they may be leaning. Once they’ve decided to lean, further details about why they so decided are less informative. In this case though there may still be some disagreement about the pace of tapering and also the crucial question of how long to wait after tapering before they start raising rates.

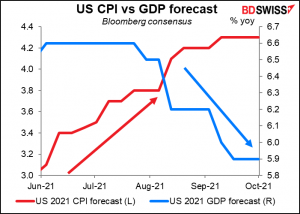

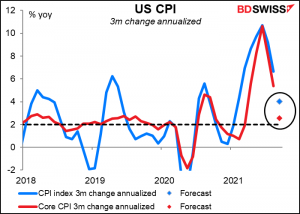

Given the fears of stagflation, the key point of interest in the coming week will be the US consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday. This always garners more attention than the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators, no matter how many times I try to explain that the Fed uses the PCE deflators as its inflation guidelines, not the CPI. Oh well, when I’m appointed King everyone will have to read my comments and follow along.

Inflation is expected to slow at both the headline and core level.

Of course, we’re still feeling some of the base effect from the price drops that occurred a year ago. If we just take the last three months’ worth of CPI figures and annualize them, you can see how the rate of inflation is slowing even more dramatically. On this basis, the core CPI is expected to show only a 2.6% annualized rate of change – a far cry from 10.6% annualized back in June.

So yes, the rate of inflation in the US is slowing dramatically. Whether this argument will win over the hawks and keep the “transitory” thesis alive is another matter.

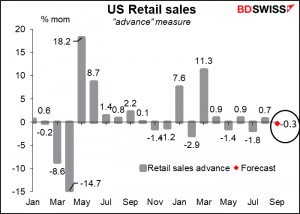

The other feature of the week will be Friday’s US retail sales. This is important because the key point for me is what will happen to the US economy as the extraordinary fiscal stimulus fades? As special Federal unemployment benefits end and the impact of the “helicopter drop” of money from heaven that spontaneously appeared in peoples’ bank accounts (including mine; even I got a $1,400 stimulus check) fades, will the US consumer be able to keep the wheels of commerce turning over at the current speed?

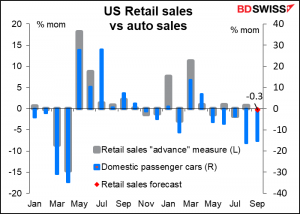

Sales are expected to be down a minor 0.3% mom.

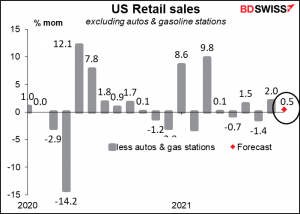

Which may well be due to lower auto sales – excluding autos, sales are forecast to be up 0.5%

Auto sales fell 15.3% during the month, probably due to a lack of cars to sell rather than a lack of demand. Some automakers have halted production of cars here and there due to chip shortages.

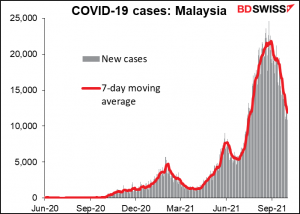

Some of the problems stem from the shutdown of a STMicroelectronics plant in Malaysia. The factory supplies automotive microcontrollers to automakers, but the re-emergence of the coronavirus has prevented employees from coming to work. Without the semiconductors, the component manufacturers can’t make their parts, and without the parts, the automakers can’t make cars. For want of a nail…

In any case, even this small decline in retail sales would leave sales 17.2% above the pre-pandemic average. That’s a lot. I wonder how long this unusually high level of demand can be sustained and what will happen if and when it falls back to normal. And if the Fed wants to hasten that event by tightening policy.

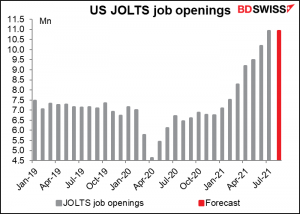

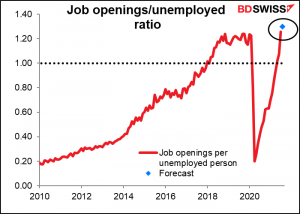

Finally for the US we also get the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) program, replete with all sorts of juicy data on the job market. What everyone focuses on is the number of job openings, which is sort of like the counterpart to the unemployment figure: not people looking for jobs, but rather jobs looking for people. It’s expected to be down slightly (some 9k) but this forecast is not particularly reliable – so far only five contributors.

Be that as it may, it would mean 1.30 jobs for every unemployed persons, vs the peak of 1.23 jobs right before the pandemic (the US equivalent of the much-beloved job-offers-to-applicants ratio of Japan, although some people in the US turn it around and express it as the applicants-per-job ratio.) This record ratio would be another indication that the US is making “substantial further progress” on the jobs front and therefore the Fed can go ahead and taper down its bond purchases.

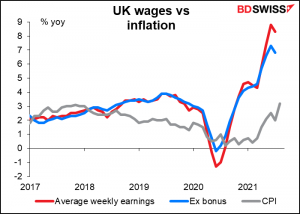

Elsewhere, it’s a big week for British indicators. On Tuesday they announce the employment data. The key point here, as far as I can tell from reading the Bank of England statements following their meetings, is the rate of earnings settlements (no forecast available yet) to see if a wage/price spiral is likely. Unlike in the US, wage settlements in Britain have been running well above the rate of inflation.

The Monetary Policy Committee also highlighted “how the economy will adjust to the closure of the furlough scheme at the end of September,” but since this set of data is for August, we won’t know for sure. But there may be a hint in the claimant count rate and jobless claims change for September that will accompany the data.

Then bright and early Wednesday we have the UK short-term indicators, including the monthly GDP, industrial & manufacturing production, and trade balance.

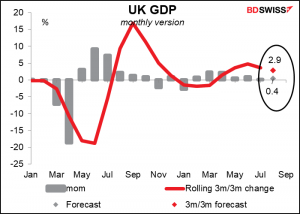

Within that esteemed group, the GDP figures are the most important (although the Bloomberg relevance index is a bizarrely low 11, compared to 92 for industrial production). The month-on-month forecast of +0.4% would be an acceleration from the previous month’s +0.1%, but the three-month/three-month rolling change would decelerate to 2.9% from 3.6%, which I think is more in line with the slowing growth that most people expect.

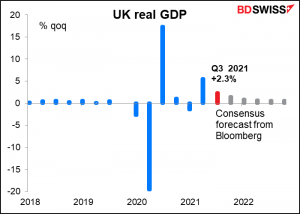

The market looks for Britain’s quarterly growth profile to slow.

I think the market is likely to take these figures as indications that growth is slowing in the UK, which could take some of the pressure off the Bank of England to tighten policy. That would probably be negative for the pound.

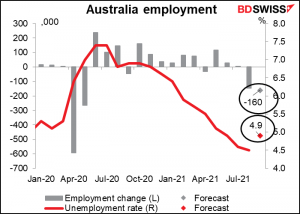

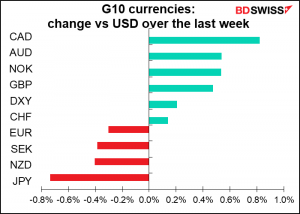

Elsewhere, Australia’s employment data Thursday will be the highlight for that country. Employment is expected to fall by 160k and the unemployment rate jump to 4.9% from 4.5%. The market will defo be devo, mate! AUD is likely to rack off. (Hey, I’m American, this is the best Australian slang I can manage.)