So… the Fed finally tapered! OK, now what do we talk about?

Now we start speculating about “lift-off” – the time when they start raising interest rates.

In the statement issued by the FOMC, the Committee set out their requirements for lift-off:

The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time

This was the major topic in Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s press conference following the meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Someone asked Powell if the Fed had met its test for inflation yet. He pointed out that

“…we’re not at maximum employment. When that is the case, we’ll look to see whether the inflation test is met. And there’s a good chance that it will be…”

In other words, while there are formally three tests to meet before raising rates – 1) maximum employment, 2) inflation at 2%, and 3) inflation on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time, there really is only one test, the employment test. That’s because inflation has been over 2% since April (core personal consumption expenditure deflator, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge) and is likely to remain so “well into next year,” so by the time the employment test has been met, the “for some time” test will probably have been met, too.

So once again the course of Fed policy comes down to the question: what is maximum employment? It used to be what was seen right before the pandemic.

So, in terms of full employment, as I discussed earlier I think at the very beginning of the recovery, the natural thing to do was to look back at labor market conditions in February of 2020, at the end of the longest expansion in our history…

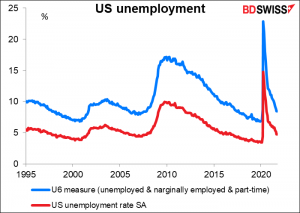

Back then, the unemployment rate was 3.5%, the lowest in some 50 years, and the U-6 unemployment rate (including part-time and those marginally attached to the labor market) was 7.0%, not far off the record low of 6.8% hit two months earlier (also in Oct ’00).

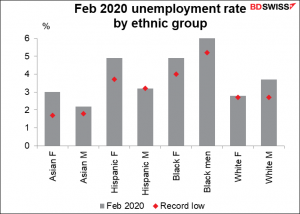

The unemployment rate was also low – although not quite at record low levels – for most minority groups as well, thus satisfying the Fed’s “broad-based and inclusive” criteria.

However, everything changed after the pandemic, Powell noted.

Now the temptation at the beginning of the recovery was to look at the data in February of 2020 and say, well, that’s the goal because that’s what we knew. We knew that was achievable in a context of low inflation. I think we’re learning that we have to be humble about what we know about this economy, which is still very COVID affected, by the way…We’re in a different world now, it’s just very different.

Asked how he defines “maximum employment,” Powell was vague – necessarily vague, I’d say. The definition is somewhat like what a judge once said about obscenity: I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it.

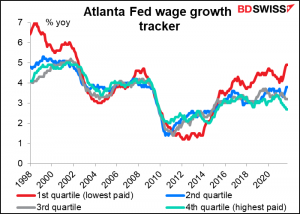

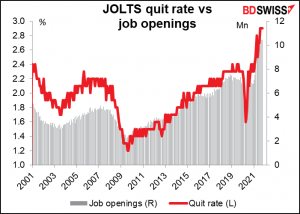

So maximum employment is, we say broad-based and inclusive goal that’s not directly measurable and changes over time due to various factors…. And of course, levels of employment, participation are part of that. But in addition, there are other measures of what’s going on in the labor market. Like wages is a key measure of how tight the labor market is. The level of quits, the amount of job openings, the flows in and out of various states. So we look at so many different things and you make an overall judgment.

Later noted the uncertainty that’s developed because of the change in peoples’ desire to work. This makes it hard to judge whether the labor market is slack or tight.

We think about maximum employment as looking at a broad range of things, unlike inflation where you can have a number. But with maximum employment, you could be in a situation hypothetically where the unemployment rate is low, but there are many people who are out of the labor force and will come back in. And so you wouldn’t really be at maximum employment because there’s this group that isn’t counted as unemployed. So we look at a range of things.

…By many measures, we are at a very tight labor market. I mentioned quits and job openings and wages and things… Many of them are signaling a tight labor market. But the issue is how persistent is that? Because you have people who are held out of the labor market of their own [volition]… They’re holding themselves out of the labor market because of caretaking needs or because of fear of COVID or for whatever reason. ..With tremendous demand for workers and wages moving up, it does seem like we’re set up to go back to a higher job creation. So that would suggest that you’re not at maximum employment.

So at the end of the day, it is a judgment thing. But of course, at the end of it also has to be a level of employment that’s consistent with price stability.

One key metric he did specific: under the new conditions, where people may be retired or otherwise out of the labor market voluntarily, a lower number of new jobs being created each month might not be the sign of a weak job market that it was previously.

Under these conditions, maybe you don’t need to see 1mn new jobs created every month to have strong job creation…you don’t have to think back to the million job months of June and July, you can just think, okay, 550 to 600 [thousand a month], we should get back on that path, then we would be making good progress.

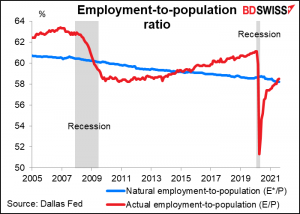

Powell’s view is backed up by some Fed research. A recent research note by the Dallas Fed said that “the labor market slack created by the COVID-19 pandemic has been absorbed. This improvement extends to women as well as specific population subgroups, including Asians, Blacks and Hispanics.”

[We use] the employment-to-population ratio (E/P) as an alternative measure of labor market conditions. The advantage of the E/P is that it is not affected by an out-of-work individual’s decision whether or not to engage in a job search and, consequently, to be counted as unemployed or out of the labor force…

Using the E/P as our measure of labor market conditions, labor market slack exists when the actual E/P is below the estimated E*/P. [The chart below] shows how the wide E/P gap created by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has closed.

In any case, Powell made it clear that although the main risk the Committee sees is higher inflation, they want to be “patient” and see what happens with employment once the Delta variant declines and people can freely choose to work or not.

…we have high inflation and we have to balance that with what’s going on in the employment market. So it’s a complicated situation, and I would say we hope to achieve significantly greater clarity about where this economy’s going and what the characteristics of the post-pandemic economy are over the first half of next year.

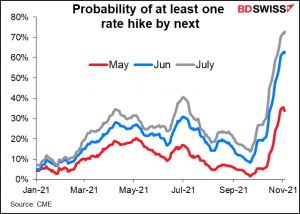

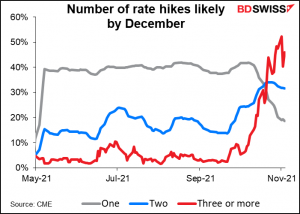

The market takes this “first half of next year” line seriously. The Committee has said that it wouldn’t raise rates while it was still buying bonds, reasoning that it would be irrational to be tightening with one hand while still providing extra stimulus with the other. Yet the market puts a small (34%) probability on a first rate hike at the May meeting – perhaps on the assumption that things go well and the Fed accelerates its tapering? For the June meeting, which is when the taper is supposed to end, the market sees a 58% probability of a rate hike and for July, a 72% chance.

And unlike the FOMC, the market thinks it probable that there will be two rate hikes – or more! – by the end of the year.

Powell didn’t push back against this pricing. Asked “do you think it’s possible or likely even that maximum employment could be achieved by the second half of next year?,” Powell responded, “So if you look at the progress that we’ve made over the course of the last year, if that pace were to continue, then the answer would be yes.“

Other things the Fed will have to consider: after they end their bond purchases, what will they do with their balance sheet? Will they just keep it at its peak level, or will they start to shrink it – quantitative tightening? Powell said that was one of the things they’d have to consider in the future.

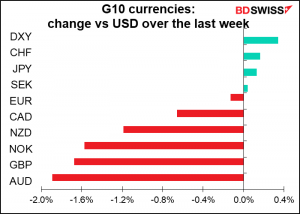

Implications for the FX market: There’s a sharp contrast between the central banks that are clearly on a tightening trend – for example, the Fed, the Bank of Canada, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and the Bank of England, (despite remaining on hold this week) — and those that are resolutely dovish – the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan first and foremost, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and perhaps the Swiss National Bank too (we’ll have to see how their intervention goes). As the US moves to tighten policy, this will give other central banks cover to do so as well without risking their currencies appreciating vs the dollar. The result may be that the currencies of those central banks that don’t go along with the rest of the pack will see their currencies weaken. The return of the “yen carry trade” seems likely, perhaps aided by the “euro carry trade” as well.

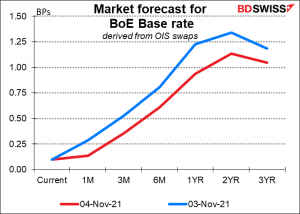

That idea was challenged Thursday by the Bank of England, which stunned the market by refraining from hiking rates despite self-declared “signals” from BoE Gov. Bailey. Given that the BoE was considered one of the more hawkish central banks, this caused a sudden reassessment of all central banks’ reaction function, and with it a reassessment of just how quickly other central banks would move.

I think though that Britain is a special case. The BoE is just waiting for more information on the impact of the end of the UK government’s furlough scheme, which affected some 1mn workers. That information will be available at their meeting. Once the Monetary Policy Committee sees the impact of that event on employment, they’re likely to go ahead and hike rates. Furthermore, Britain is still in upheaval thanks to the never-ending Brexit negotiations, which are about to trigger a trade war with the EU. We can’t generalize from the UK’s hesitation to other central banks. Look at Poland, which hiked rates 75 bps during the week and said it would do “whatever it takes” to fight inflation!

Indicators next week: US CPI, JOLTS, UK GDP

The second week of the month usually has few indicators scheduled, and this month is no exception.

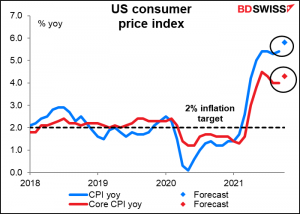

The highlight as usual will be the US consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday. It’s somewhat anticlimactic now that the Fed has begun tapering and admitted that “supply bottlenecks and shortages will persist well into next year and elevated inflation as well,” as Powell said. So even if inflation rises further, what impact will it have on policy? It’s already in the price.

Inflation is indeed expected to rise further, at both the headline and the core level.

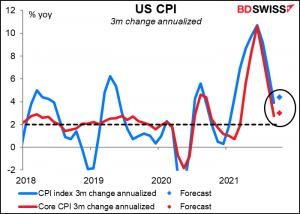

Nor can this be attributed solely to “base effects” – if we take the three-month change and annualize it, that too is expected to rise, albeit not to the levels seen earlier this year. But as I said, this is already in the price and so shouldn’t have much impact on the dollar.

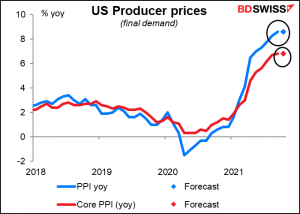

On the other hand, US producer prices (Tuesday) are expected to rise at the same rate, although admittedly quite a high rate.

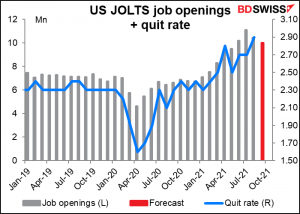

Friday’s US Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) program will be closely watched both for the number of job openings and for the quit rate, or percent of people who voluntarily leave their jobs every month (no forecast). The latter indicator, recently at a record high, has been widely quoted as a sign of a tight labor market, because generally speaking people don’t quit their job unless they’re confident that they’re going to be able to get another one.

(The “market consensus forecast” in this graph is a misnomer; there’s only one forecast so far: 10.0k new jobs, down from 10.4k last month.)

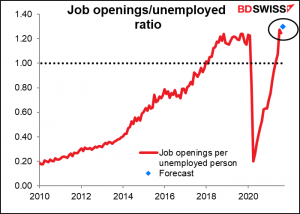

Other similar indicators are the number of openings relative to the number of unemployed persons, or what’s known in Japan as the “job offers-to-applicants ratio,” a relationship that’s beginning to get more traction in other countries recently. That hit a then-record high of 1.28 in July but came down to 1.25 in August. Given the one forecast for 10.0k job openings in September, that would push the ratio up to a record high of 1.30, further confirming the idea of a tight labor market.

Thursday is a Federal holiday in the US (Veteran’s Day) so the US jobless claims will come out on Wednesday instead. Friday’s Commitments of Traders (CoT) report on the other hand will be delayed until next Monday. Thursday is also a holiday in Canada.

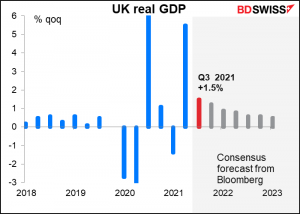

The focus Thursday will be on the early-morning UK short-term indicators, which this month include the quarterly GDP as well as industrial & manufacturing production and trade. The GDP figure is expected to be the peak for now; the profile from here on out is diminishing.

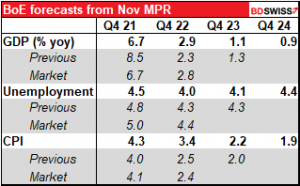

The Bank of England Thursday revised down sharply its end-year forecast for GDP growth this year. It revised it up for next year, but down for 2023 and has an even lower forecast for 2024.

One unusual highlight during the week for those interested in cryptocurrencies: the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies (BOFIT) will celebrate its 30th anniversary with a conference Tuesday. There will be a panel discussion on central bank digital currency; “Digital currencies around the world – what are the policy implications?” It will be chaired by Bank of Finland Gov. Olli Rehn and panellists will include the central bank governors of Russia and China as well as Fabio Panetta, the European Central Bank’s point man for the subject.