It’s clear that most central banks want to tighten policy nowadays. Not surprising, as inflation has proved less “transitory” than they expected a year ago. I’m not sure what tighter monetary policy will do to combat inflation that’s caused by supply bottlenecks – higher interest rates won’t help to enlarge ports or build more semiconductor factories. But that’s the only tool that Officialdom has and so they’re forced to use it. We saw that from two central banks this past week (although one delayed any action due to the virus) and we’ll probably see it from at least one, maybe two next week – but probably not from the third.

The US Fed has shown us just how quickly things can change. In September the members of the rate-setting FOMC forecast that there would be no rate hikes in 2022. In November they voted to taper down their bond purchases by June – which implied raising rates sometime after that. In December they doubled the pace of tapering and forecast three rate hikes. And now about a month later the market is looking for five or maybe even six hikes this year. From zero to six in four months!

This rather complicated graph gives the market’s estimate for the probability of various numbers of rate hikes in 2022. You can see that until the middle of September, the market assumed there would be either no rate hikes (red line) or maybe one (blue line). Then around mid-September, two (grey line) started moving up, only to be surpassed in early November by three (green line). In early January though four (purple line) took the lead, now challenged by five or more (gold line).

There are three central bank meetings this coming week: the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Tuesday and the Bank of England and European Central Bank (ECB) on Thursday. Only the Bank of England is likely to change rates. That doesn’t mean that the other two will be devoid of interest (well, the ECB might not be exactly riveting) but it just means we’ll have to read their comments to get an idea of what they’re thinking.

Bank of England: on the move

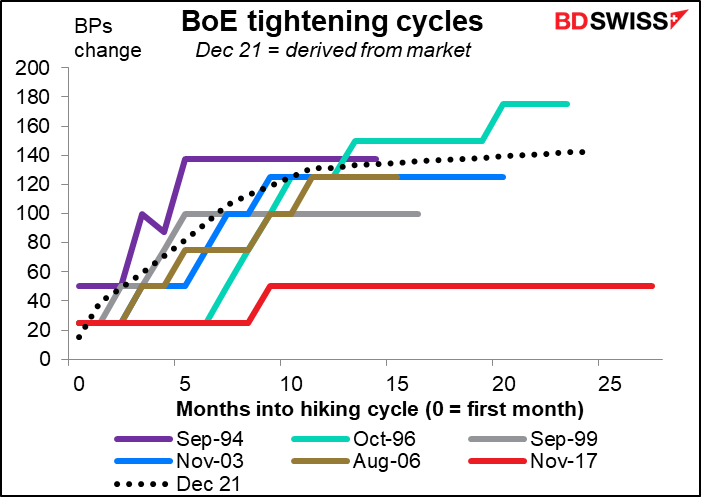

The market expects a relatively rapid hiking cycle by the Bank of England. At its last meeting it unexpectedly (well, I didn’t expect it anyway) hiked by a modest 15 bps, taking Bank Rate from 0.10% to 0.25%. At this meeting it’s widely expected to hike another 25 bps.

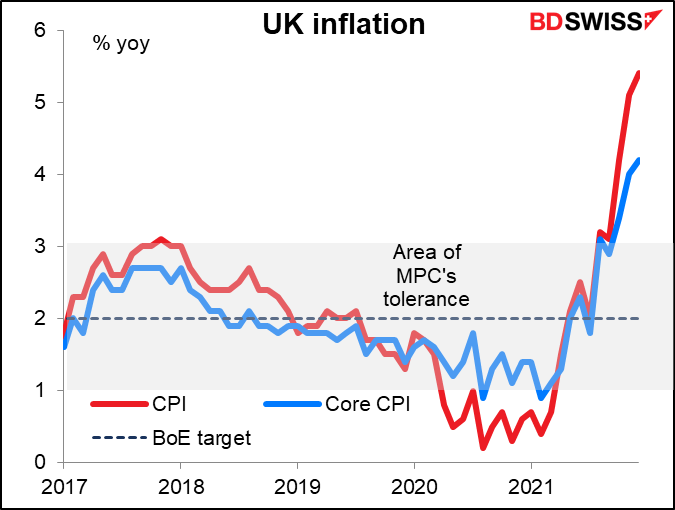

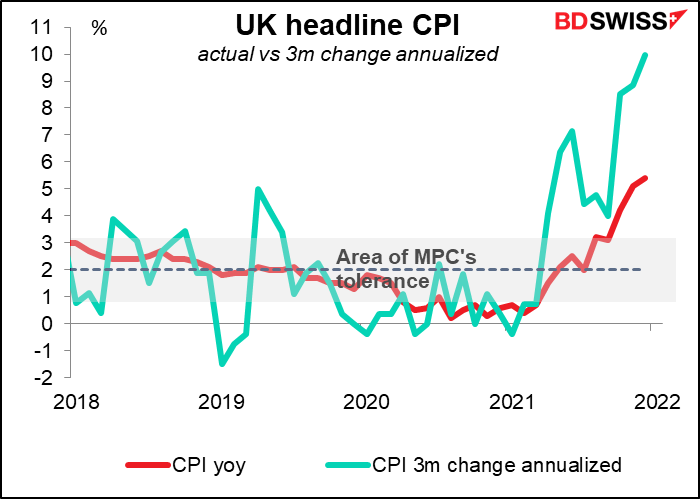

I only have to show one graph to explain why they’re likely to hike. With CPI inflation at 5.4% yoy and expected to peak at over 6%, they’re bound to act.

Nor is there any sign of inflation slowing. On the contrary, if we take the three-month change in prices and annualize it, inflation is running at over 10i% yoy.

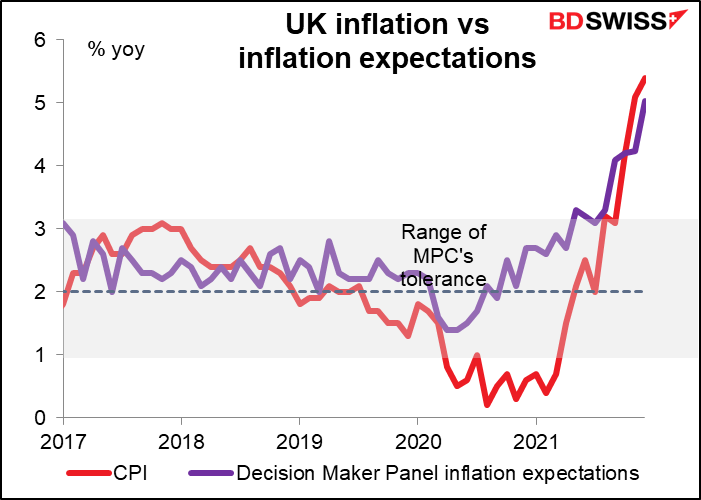

Inflation expectations are rising too, according to the Decision Makers’ Panel, a monthly survey of senior British executives conducted for the Bank of England.

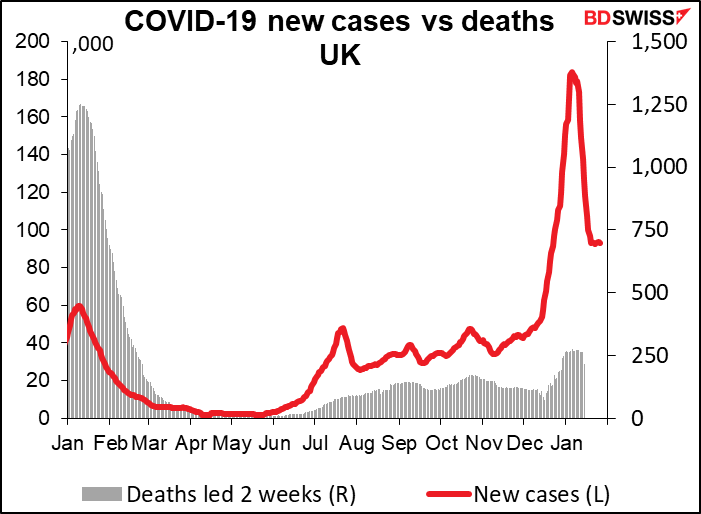

Moreover Britain seems to be “over” COVID-19, although COVID-19 doesn’t seem to be “over” Britain. While the number of new cases has come down it’s still at a level that previously would’ve caused total lockdown. Instead, the government lifted all restrictions and said they weren’t going to be put in place again. That’s likely to boost economic activity.

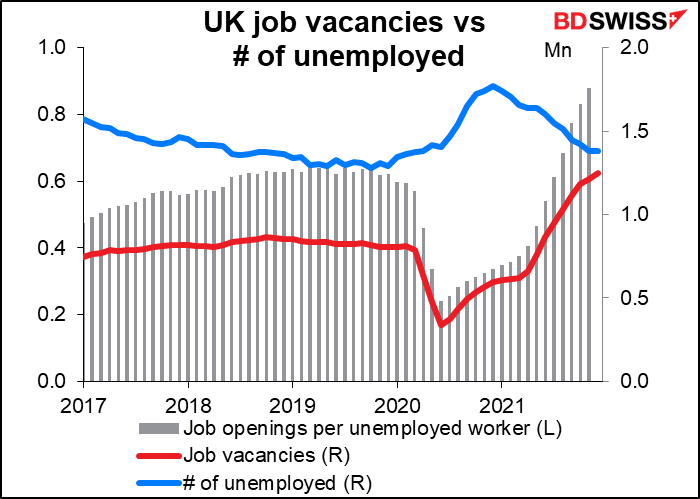

Moreover the labor market (oh, sorry, labour market) is quite strong. The unemployment rate of 4.1% is almost back to its pre-pandemic Feb. 2020 rate of 4.0%. There are a record number of job openings and the job-openings-to-unemployed ratio is approaching the magic number, 1.0. At this rate, companies might actually start having to pay higher wages to working people. Shock horror chaos! We can’t have that now, can we?

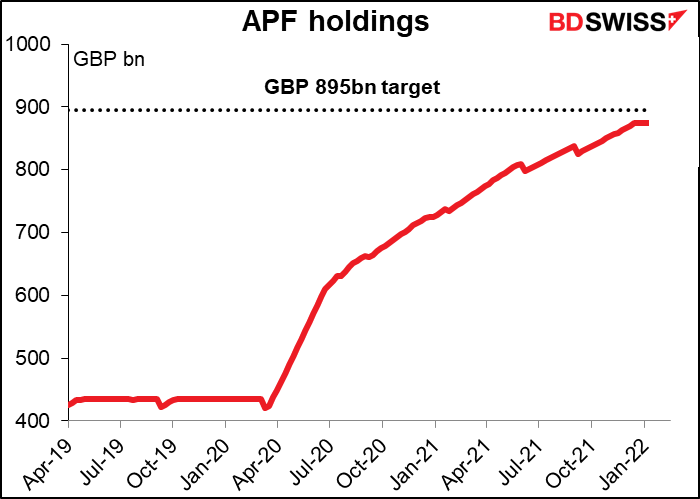

Along with the widely expected 25 bps rate hike, the statement is likely to talk about the Bank’s balance sheet, which is an issue all central banks face now that the era of “quantitative easing” is segueing into “quantitative tightening.” The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is likely to discuss what to do with the bonds in its Asset Purchase Facility (APF), the place where it stashed the bonds it bought in its QE program. The APF hit its purchase target last December and has since stopped buying bonds.* The question now is, what to do with maturing bonds? Do they reinvest the proceeds? Not doing so would mean allowing their balance sheet to shrink. I expect that they will decide not to reinvest maturing bonds and will allow the APF to slowly melt away. This would not be a major hit to the bond market however as maturities this year are expected to be only GBP 39bn or some 4.3% of the APF.

(*Close observers will notice that the graph shows a gap between the APF’s purchases and the target. That’s accounted for by GBP 20bn of corporate bonds the APF also holds.)

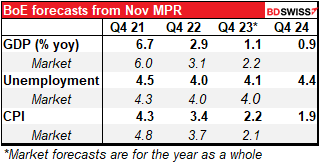

Finally, the Bank will also publish a new Monetary Policy Report with updated forecasts. Looking at how their November forecasts compare with the market, they could raise their forecasts for both growth and inflation this year, which would only make it easier for them to justify tightening.

European Central Bank: Nothing Doing

By contrast, the ECB probably will end the day with no change. They have a whole alphabet soup’s worth of programs: the PEPP (Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme), the APP ( Asset Purchase Programme), and TLTROs (Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations).However none of them is ripe for tweaking at this time.

Nor is there any QT on the horizon, at least not as concerns the bond purchase programs. The ECB has pledged to fully reinvest maturing bonds in the PEPP at least until the end of 2024. For the APP, it’ll continue to reinvest them “for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates.” An “extended period of time” is thought to be about two years.

That doesn’t mean the ECB is frozen, just that nothing is likely at this meeting. For example, they may take advantage of the end of the PEPP in March to announce some other changes, such as discontinuing the discounted TLTRO interest rate. That would encourage banks to repay some of these loans, which have increased by EUR 1.5tn since the beginning of the pandemic. That’s a form of QT in that it would cause the ECB’s balance sheet to shrink. (The ECB’s Survey of Monetary Analysts shows that the markets expect a TLTRO repayment of EUR 941bn this year.) But even that is expected to be a non-event – the ECB appears to believe its impact on financial conditions will be neutral.

So what’s to look for in this meeting? Just more of the usual from ECB President Lagarde:

However, the minutes also warned that the Eurozone economy was “not out of the woods yet.” And Governing Council member Schnabel also warned recently that hiking rates too early “could potentially choke off the recovery.” Thus they have to strike a balance, perhaps by switching the emphasis from when they’re likely to start hiking rates to what kind of inflation outlook would provoke them into acting.

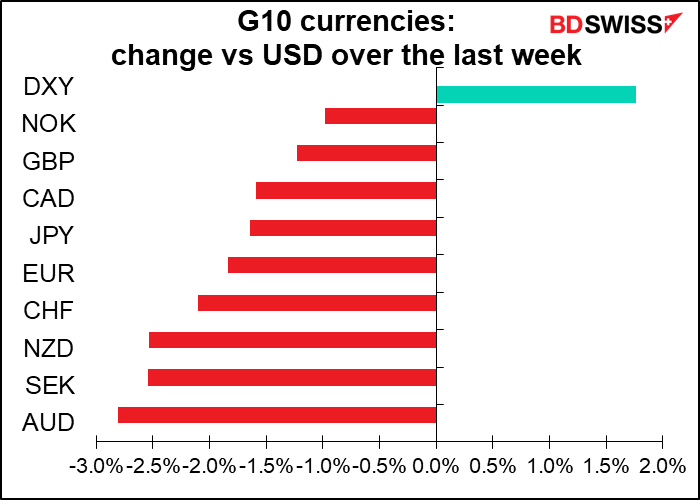

Either way, I don’t expect this meeting to have that big an impact on the euro except insofar as it may emphasize the divergence in policy between the aggressive Fed and the cautious ECB.

RBA to market: we give up!

Speaking of uncertainty, the RBA has been getting less and less certain about the future. In October it said it was likely to keep policy steady until 2024. In November it moved this to “the end of 2023.” In December it abandoned any attempt to put a date on it and just said that meeting the necessary criteria “is likely to take some time.” Thanks much for that informative statement!

The criteria that they set out for tightening seem to depend on a wage/price spiral developing:

The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range. This will require the labour market to be tight enough to generate wages growth that is materially higher than it is currently.

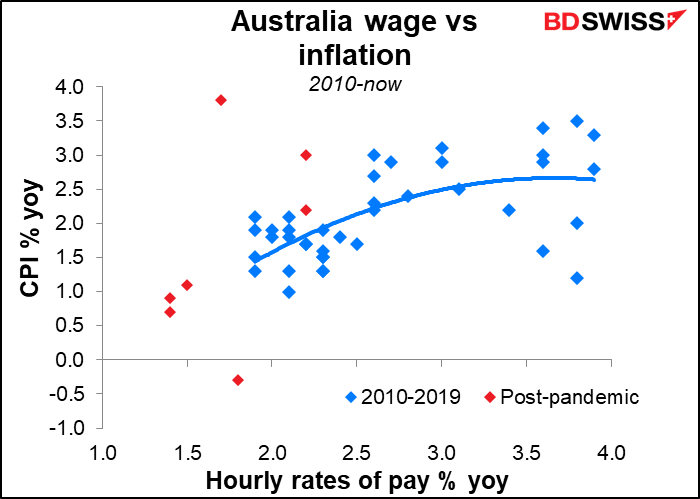

I’m sorry but I don’t see any connection between wages and inflation in Australia. Inflation has been 2% when unit labor costs were falling by 4% and it’s been 1% when unit labor costs were rising by 3%. I tried leading inflation by 1 year so that today’s wages line up with next year’s inflation but the graph doesn’t look any better.

One might well argue that the experience of 1985 isn’t relevant to today. So let’s just look at the last 10 years or so, post-Global Financial Crisis. That seemed to have had some relationship up until the pandemic, but the relationship may have broken down.

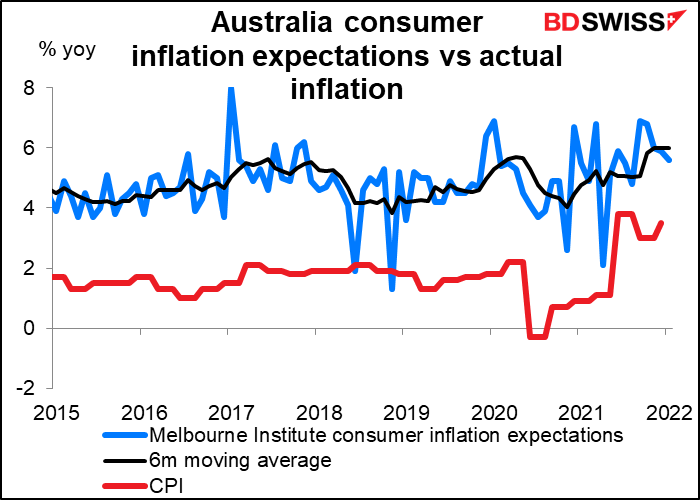

At any rate, the fact is, wage settlements or no wage settlements, inflation is not “within the 2%-3% target band” but rather above it (3.5% yoy). The trimmed mean inflation rate, the RBA’s preferred measure of inflation, went above 2% in Q3 last year and was at 2.6% yoy in Q4, the top half of their target range. (The trimmed mean inflation rate is the average rate of inflation after “trimming” away the 15% of items with both the smallest and largest price changes so as to leave only the less volatile items.) So the only question is whether it’s “sustainably” within the target range. If Q1 inflation is in similar territory, they’ll have a hard time arguing that inflation is not “sustainably” within the target range.

Especially since inflation expectations are moving up, too. Central bankers live in terror of inflation expectations becoming “unanchored.” That’s exactly what’s happening now in Australia. If the RBA is worried about wage settlements being too low now, just wait to see what happens once expectations of higher inflation become entrenched and negotiations continue on the basis that workers expect inflation to keep rising.

The Board does have one decision to make at this meeting. They’ve been buying AUD 4bn of Australian government bonds a week and pledged to continue doing so “until at least mid-February 2022.” They now own some AUD 350bn of Australian government, state, & territory bonds out of a total AUD 833bn outstanding government bonds, or around 42% of the total (not including state & territory bonds; I don’t know how much of those are outstanding.) At their December meeting they said they would “consider the bond purchase program” at this meeting. The criteria they said they’d use to decide whether to continue with the program are:

- “the actions of other central banks”

- “how the Australian bond market is functioning”; and

- “most importantly, the actual and expected progress towards the goals of full employment and inflation consistent with the target.”

How do they look now?

- The Fed has paved the way for other central banks to stop buying bonds.

- I can’t speak to it.

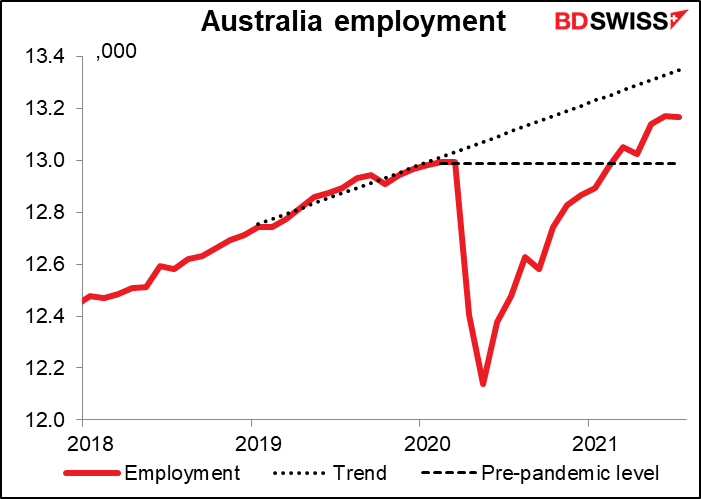

As we discussed, the inflation picture is already over the top. As for employment, the unemployment rate is below and the participation rate above where they were before the pandemic (4.2% vs 5.1%, 66.10 vs 65.90) as is the total level of employment.

Accordingly, I expect them to announce that they will stop their bond purchases, effective mid-February.

I also expect that they will abandon their emphasis on wage growth, which is falling far behind the reality of inflation, and change their forward guidance to allow for the possibility of a rate hike in the not-too-distant future.

Will that affect AUD? The sad fact is that while the RBA may have no idea when it’s likely to move, the market is already pricing in a rate hike at the June meeting. Australia’s inflation data is only released quarterly – the next one is April 27th, in plenty of time for their May 3rd meeting. It’s conceivable then that they could hike in May — there’s already a 64% chance of a rate hike priced in for that meeting. This week’s meeting could increase that probability, which would probably cause AUD to appreciate.

The coming week’s data: NFP plus OPEC+

There’s a surprising amount of data coming out this week too. The final purchasing managers indices will be released, manufacturing on Tuesday, service-sector on Thursday. Of course as usually the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) versions will be released on those days in the US.

For the EU, Q4 GDP will be released on Monday, as will German CPI. EU-wide CPI will follow on Thursday (not Wednesday as it usually would). German factory orders come Friday.

Japan employment data are out Tuesday as are Canadian employment data on Friday.

China will be out on holiday all week for the annual Lunar New Year holiday, which usually sees the greatest migration on earth as hundreds of millions of people head to their place of origin to celebrate with their families. Not sure if it’s happening this year though with COVID-19 restrictions.

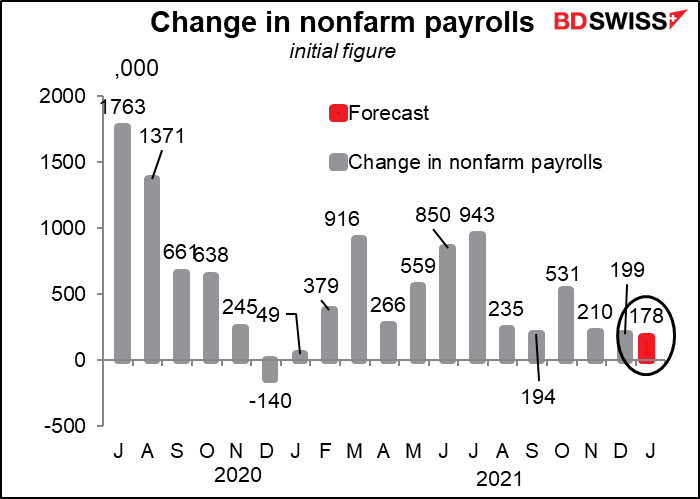

The big item this week is the US nonfarm payroll report (NFP) on Friday, preceded as usual by Automated Data Processing (ADP)’s estimate on Wednesday. Remember as usual though that the ADP report attempts to forecast the final version of the private payrolls figure, which is not the same as the initial version of total payrolls (including government). And in any case it’s not very good at that aniyway, so it’s not a reliable guide at all to what the NFP number will be.

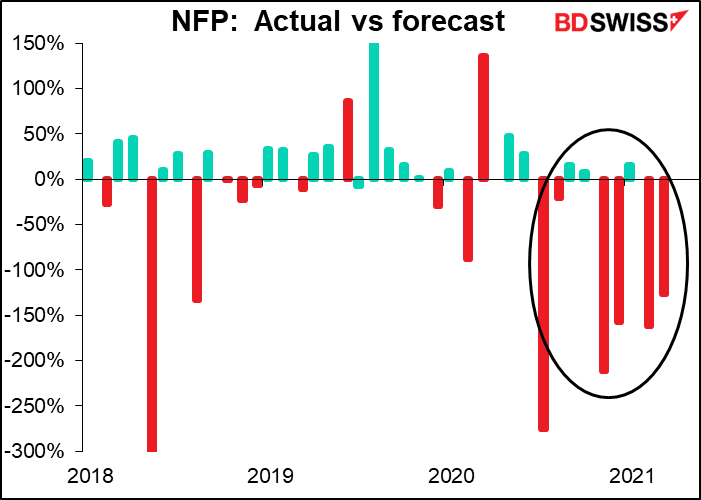

The NFP figure has come in below economists’ forecasts for six of the last nine months. As a result we’ve been bombarded with comments about how “disappointing” the increase in jobs is. It’s almost as the NFP has an obligation to meet economists’ forecasts. Let me tell you a secret: it’s the economists’ job to forecast the NFP number, not the NFP’s job to meet the economists’ forecasts. If the actual figure doesn’t meet the forecasts, it doesn’t mean the number was disappointing, it means that the forecasts were wrong. That’s all.

It’s clear that something major has changed with the US labor market. Economists’ forecasts are based on regression analysis of past relationships and are therefore unable to capture this new “something” and predict it accurately. That’s a problem for the economists.

Having said that, they seem to be wising up. This month the forecast is for an increase of only 178k new jobs. That would be pretty low – the lowest since January of last year. But maybe it’s all the US can do when people don’t want to work.

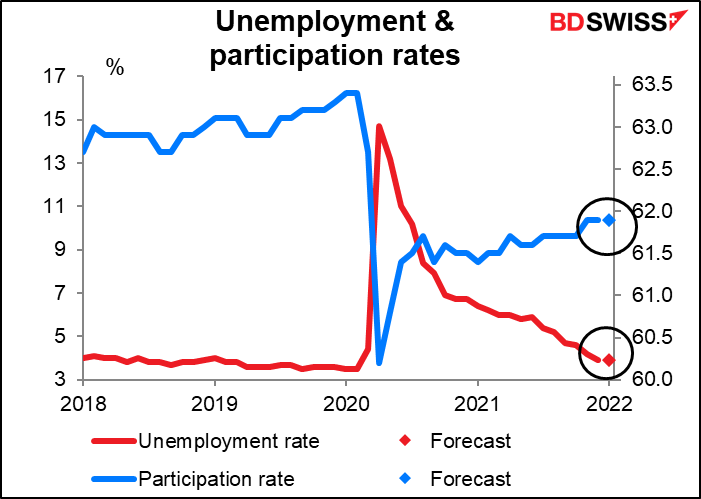

The unemployment rate and participation rate are both forecast to remain unchanged.

Of course these are only preliminary forecasts, So far Bloomberg only has 16 contributions to their survey. Last month by the time the figure was announced there were 67 estimates. So these numbers may change substantially by next Friday.

The main point is though that with the Fed already set on a tightening path, it would take a bombshell surprise in the figures – a fall in jobs and a rise in unemployment – to deflect the Fed from its path. Any less and they’ll stick with what they’ve determined. Of course a blowout figure that sent the unemployment rate down below its pre-pandemic level and a big increase in participation and they might have the courage to hike by 50 bps at a time. That would be positive for the dollar.

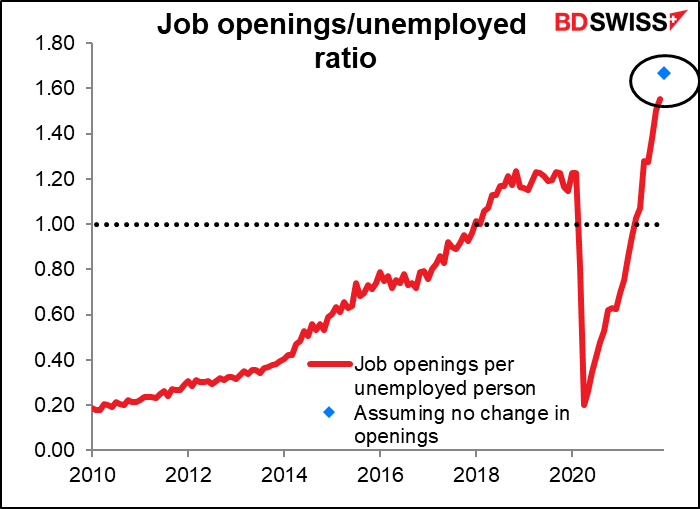

Unusually, the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) will also be released this week (Tuesday). No forecast yet there. But if it’s just equal to the previous month’s figure, then the job openings/unemployed ratio will rise further to a record 1.67, further confirming that the US has reached the Fed’s goal of “maximum employment.”

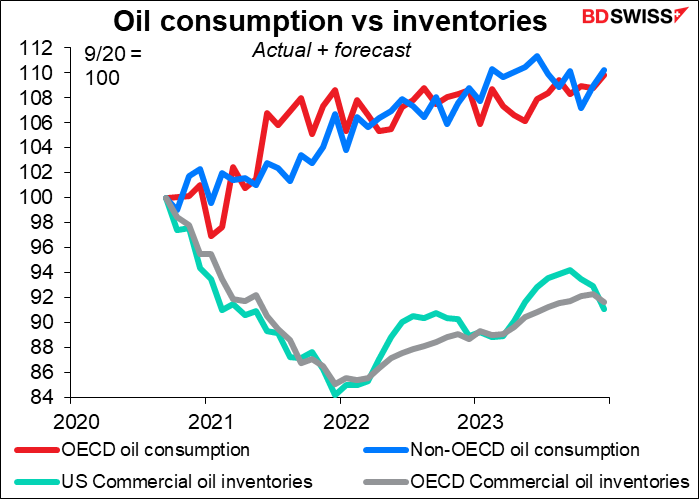

Finally, there’s the usual monthly OPEC+ meeting on Wednesday. With prices still rising, it’s likely – quite likely – that they’ll agree to continue on their current, already-agreed path of increasing production by 400k barrels a day (b/d) every month. Oil consumption is forecast to rise this year as are oil inventories, meaning there should be plenty of demand to absorb the group’s output without denting prices. The only thing is, with so many of their members near or at maximum capacity already, can they increase their output by 400k b/d?