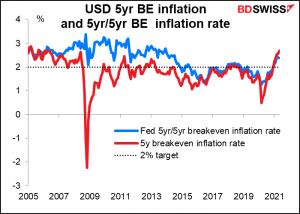

I’ve written about it several times in my weeklies recently but it’s my guess I’m going to write about it several more times too. Inflation is the key issue nowadays, particularly in the US. Or more accurately perhaps I should say inflation and the Fed’s reaction to it.

Dallas Fed President Kaplan (NV) Tuesday said he had “better visibility” and “more confidence” in the economy and that it was time “to at least start discussing” how the Fed would go about tapering down its bond purchases. He said the Fed should “start having those discussions sooner rather than later,” a line that he repeated Thursday.

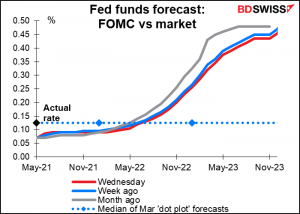

My impression though is that Kaplan, a non-voter, is if not alone, then at least pretty lonely on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Wednesday we heard from no fewer than five of the 18 Committee members and they were unanimous: not yet. Gov. Bowman (voter), Chicago Fed President Evans (voter), Boston Fed President Rosengren (non-voter), Cleveland Fed President Mester (non-voter), and Vice Chair Clarida (voter) all agreed: there’s little risk of inflation remaining persistently above their 2% target and it’s too early to start even talking about tapering.

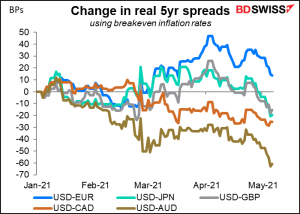

The market disagrees, however. Inflation expectations continued to rise, with the five-year breakeven inflation rate hitting the highest level since 2008 and the five year/five year forward breakeven inflation rate (the inflation rate that the market thinks will prevail for five years starting five years from now) at 2.68%, which I would say qualifies as “sustainably” over the 2% target.

It looks to me like the Fed is winning the battle for minds insofar as its intentions are concerned, even if it hasn’t convinced the market that higher inflation will be “transitory,” as a whole parade of officials have attested. Market estimates for the future pace of tightening have been coming down even while inflation forecasts have been moving up.

The result has been a decline in nominal Treasury yields and with it, an even more precipitous decline in real Treasury yields (nominal yields – breakeven inflation rate).

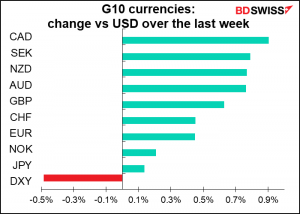

This phenomenon has hit the US more than other countries. As a result, the dollar’s real yield advantage over other currencies has been largely eroded in recent weeks. That’s likely to be a negative for the dollar.

Coming week: lots of inflation data

US inflation will be in focus next week as well as the US releases its consumer price index, producer price index, and import prices. China releases its inflation data on Tuesday.

Normally the CPI is the only major US indicator the second week of the month, but this month the US retail sales and industrial production have slipped in on Friday, along with U of Michigan consumer sentiment, meaning Friday will be a major day for US indicators. The Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report on Tuesday may take on additional importance as the Fed focuses more on the labor market than on inflation.

Wednesday is short-term indicator day for the UK, this month including Q1 GDP as well as industrial & manufacturing production and trade.

Japan comes back to work after the Golden Week holiday to find USD/JPY slightly higher than where they left it (around 109.17 vs 108.60). The only major Japanese indicator out this week is the current account on Thursday.

There are no major central bank meetings during the week. As for speakers, Bank of England Gov. Bailey speaks twice (once at a seminar on LIBOR with NY Fed President Williams), but he gave a press conference this past week so don’t expect much new. Fed Govs. Clarida and Brainard speak.

This April US consumer price index (CPI) is a textbook example of what’s meant by “base effect.” The mom change is expected to be a fairly modest +0.2% mom, but because prices fell 0.7% mom in April 2020, the yoy rate is expected to leap to 3.6%, the highest since September 2011.

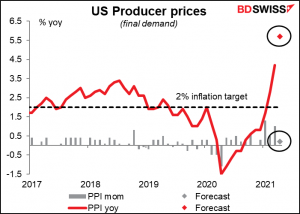

Producer prices too are expected to show the same phenomenon – a relatively modest mom increase but a leap from a year earlier.

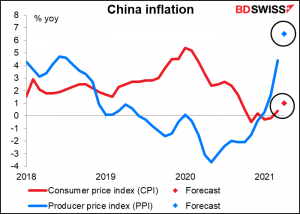

We don’t have mom figures for China, but we can assume the same phenomenon behind the expected jump in China’s producer price index. It was down 3.7% yoy in April 2020.

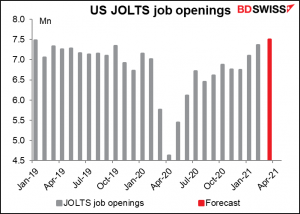

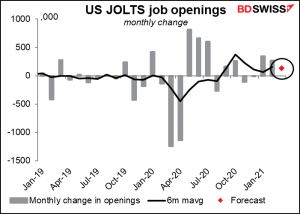

The Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report used to be quite important under Fed Chair Yellen, who was a labor economist by training. I think it could gradually come back into fashion as the labor market displaces inflation as the Fed’s main concern.

The market is looking for 7.5mn job openings, considerably (17.4%) higher than before the pandemic. But that stands to reason as companies that have shut down reopen.

That would be an increase of 133k jobs from the previous month. That compares with an average of 153k a month over the last six months so it would be nothing to get excited about.

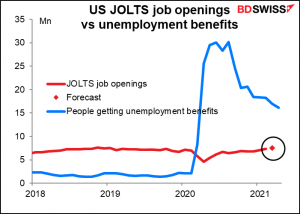

It’s also well below the 16.2mn people who are unemployed at the moment, so it’s no surprise if it takes some time for the unemployment rate to go back down.

Speaking of which, some academic papers recently attempted to answer the question: is the reason why so many people are still unemployed in the US because they’re getting more money on the dole than they would working? Special pandemic payments have indeed been relatively high. Many minimum-wage workers are getting more sitting home watching Netflix than they would get flipping burgers. You might be interested to know that the studies all concluded the same thing:

- “Overall, our evidence suggests that employers did not experience greater difficulty finding applicants for their vacancies after the CARES Act, despite the large increase in unemployment benefits.” Job Search, Job Posting and Unemployment Insurance During the COVID-19 Crisis

- “We find no evidence that more generous benefits disincentivized work either at the onset of the expansion or as firms looked to return to business over time.” Employment Effects of Unemployment Insurance Generosity During the Pandemic

- A third paper, Aggregate Employment Effects of Unemployment Benefits During Deep Downturns: Evidence from the Expiration of the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, looked at the question from a different point of view: what happened when the benefits ended. It found little evidence that places where the benefits ended earlier had any earlier recovery in employment, which is basically the same thing.

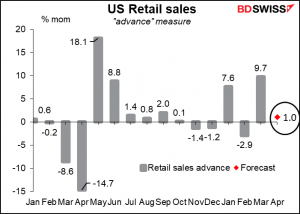

US retail sales is an important indicator for the consumer-driven US economy. Even after March’s 9.7% mom surge, powered by the $1,400/person stimulus checks, retail sales are expected to rise further – presumably because people weren’t able to spend all of it in March, or some people didn’t get their checks on time. I think another indication of strong demand would tend to confirm the narrative that the US economy is roaring back, perhaps pushing stocks higher and the dollar lower.

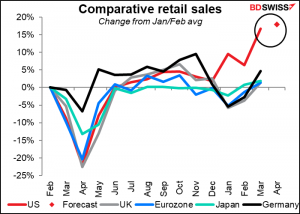

When it comes to retail sales, the US is in a class of its own internationally.

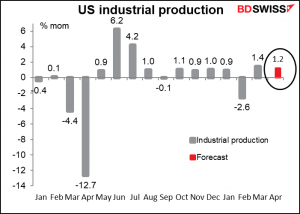

US industrial production on the other hand is recovering steadily but not dramatically.

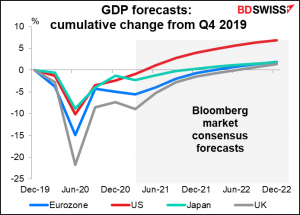

The recovery in industrial production has been more in line with the other major countries – and not yet back to pre-pandemic levels, in contrast to retail sales, which even in February, before the payments went out, were 6.7% above pre-pandemic levels.

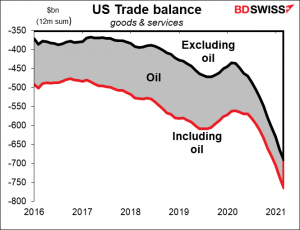

That difference is what’s pushed the US trade deficit to a new record wide despite the much smaller deficit in oil nowadays. That used to be a negative for the dollar, but I’m not sure anyone pays attention to it nowadays – capital flows are more important. It is however a big positive for other countries, which benefit from the spillover of US fiscal stimulus. Canada, which sends 49% of its exports to the US, is probably the major beneficiary. Notice from the table at the bottom what was the best-performing currency this week.

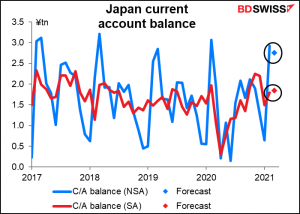

Japan’s current account surplus on the other hand is expected to rise slightly on a seasonally adjusted basis, although that would be a small fall on an unadjusted basis. Japan is benefiting from the relatively strong recovery in China.

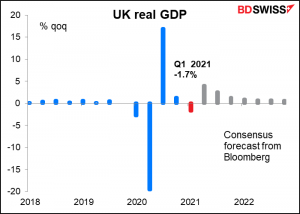

Wednesday morning is UK short-term indicator day, when they announce GDP, industrial & manufacturing production, and trade data.. The most important point there will be the Q1 GDP figure. It’s expected to be down 1.7% qoq, However, the market is looking for a pretty healthy rebound of +4.0% qoq in Q2.

That would still mean the UK recovering back to pre-pandemic levels of output by Q2 next year, behind Japan (Q4 2021) and a little after the Eurozone (Q1 2022). The US is well ahead in this race; it’s expected to return to pre-pandemic output levels in Q2 this year.