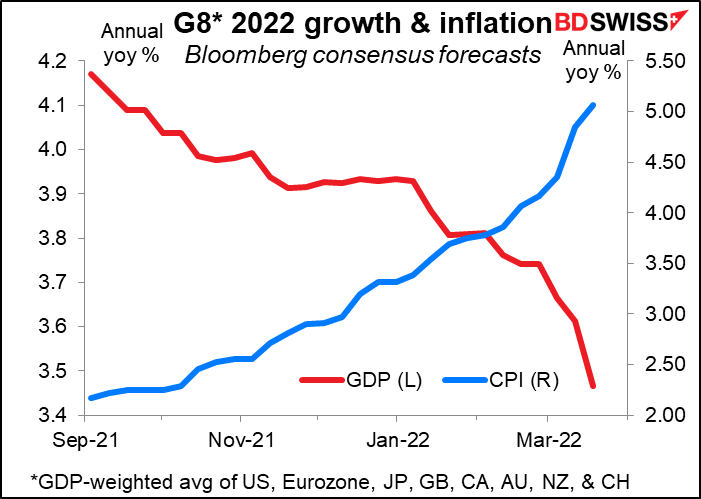

Central banks and pundits are agreed – the war in Ukraine will increase inflationary pressures and dampen growth while weighing on sentiment.

Here’s what the US Fed and the Bank of England said this week on the subject:

Federal Open Market Committee March 16 – Hiked 25 bps

The implications for the U.S. economy are highly uncertain, but in the near term the invasion and related events are likely to create additional upward pressure on inflation and weigh on economic activity.

Bank of England March 17 – Hiked 25 bps

Regarding inflation, the invasion of Ukraine by Russia has led to further large increases in energy and other commodity prices including food prices. It is also likely to exacerbate global supply chain disruptions, and has increased the uncertainty around the economic outlook significantly. Global inflationary pressures will strengthen considerably further over coming months, while growth in economies that are net energy importers, including the United Kingdom, is likely to slow.

That’s certainly what the market thinks. Growth forecasts for this year have been revised down and inflation forecasts revised up.

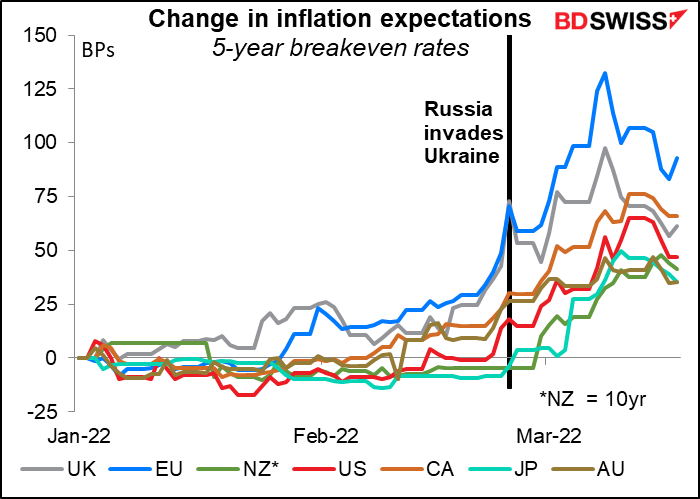

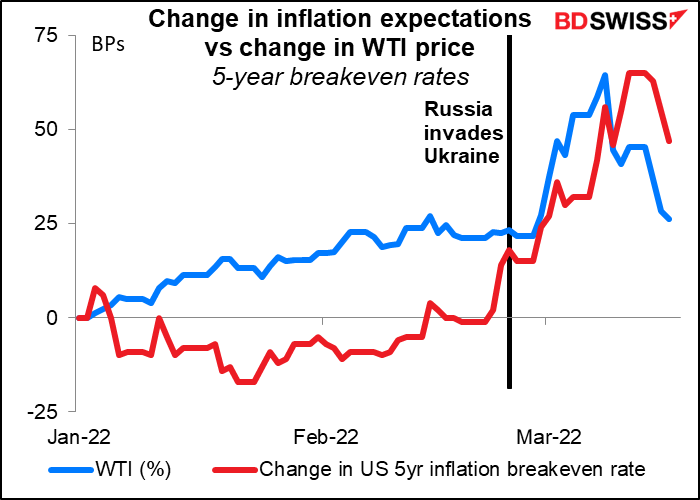

But oddly enough, inflation expectations, which rocketed after the invasion, have been coming down recently.

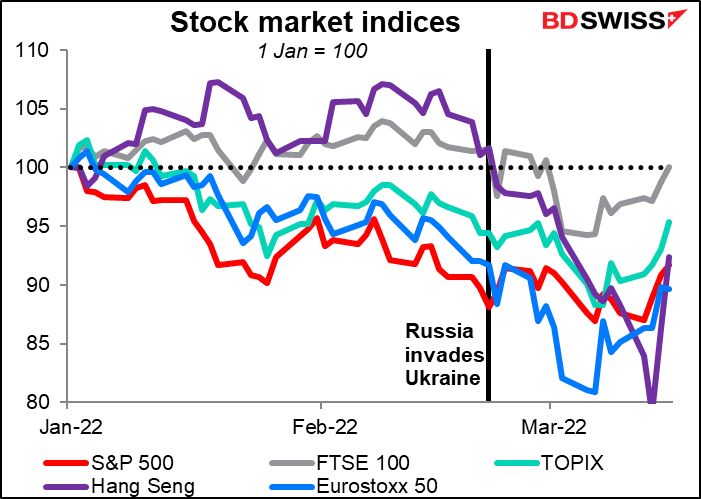

And stock markets have started to recover.

What’s the connection? My guess is that it all comes down to oil. If the price of oil falls, then inflation won’t be as high, central banks won’t have to tighten as much, and consumer spending will hold up better. If oil goes back up, then inflation will be higher for longer, central banks will have to tighten more, consumers will have to spend more of their income buying gasoline less buying iPhones, and we’ll be back to worrying about recession and stagflation.

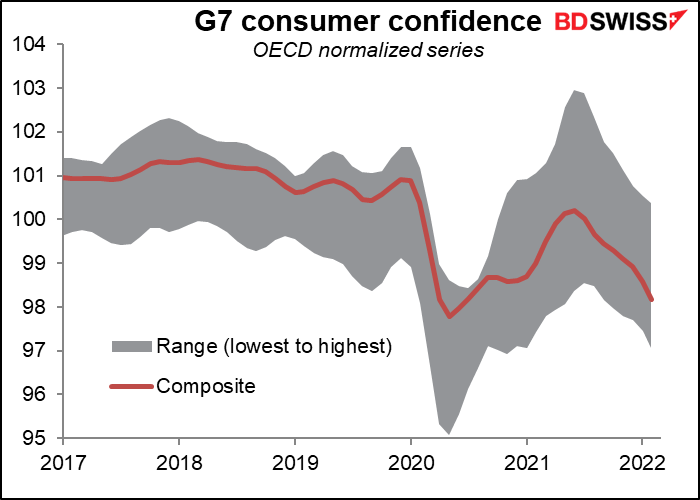

Meanwhile, consumer confidence is falling. These OECD indices do not encompass the latest developments.

Economies are fragile and sentiment is fragile. We may see more central banks like the Bank of England take a more cautious approach to tightening (“some further modest tightening in monetary policy may be appropriate” rather than last month’s “is likely to be appropriate”) rather than the Fed, which forecast that it would hike rates into restrictive territory for the first time in over a decade.

This week: Preliminary PMIs, UK & Tokyo CPI, UK Budget, Powell speech

The indicator calendar isn’t that full but there are some key indicators coming out.

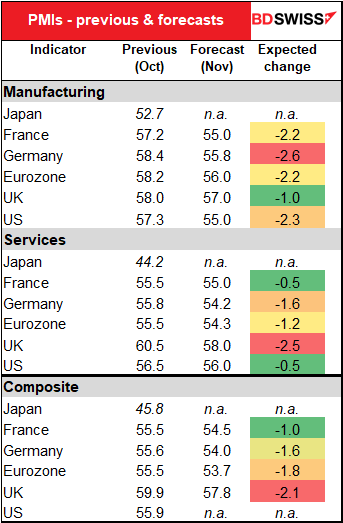

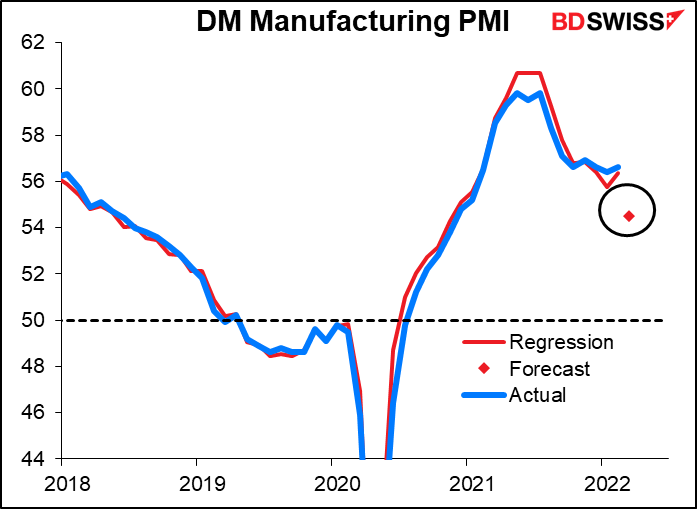

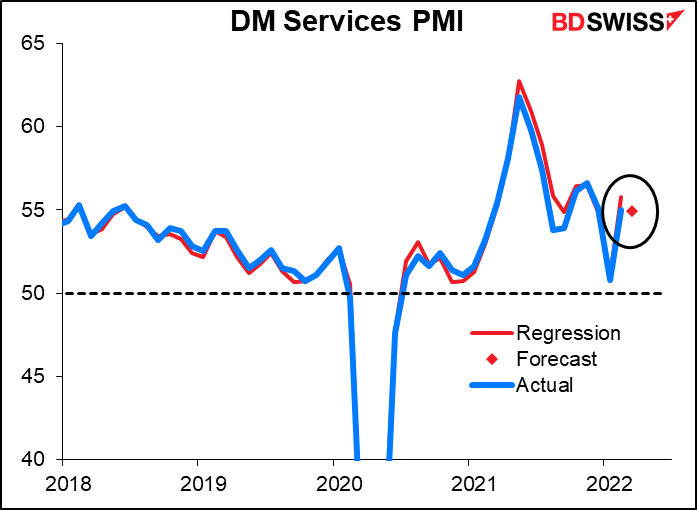

First and foremost are the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major industrial countries (Japan, Eurozone, UK, and US – Australia too but nobody cares about that one, apparently) on Thursday.

They’re expected to be bad, especially manufacturing. That’s a change. For the last two years the lockdowns to deal with the virus have hit the service sector hardest. Now those restrictions are pretty much lifted; instead it’s the surge in energy prices and the disruption to world trade that’s affecting economic activity.

We should keep things in perspective. The PMIs are all expected to say well in expansionary territory except for long-suffering Japan. That means any talk of “stagflation” is premature, much less “recession.” But certainly this isn’t the direction we want to see things going in.

Based on a regression analysis of the overall developed market PMIs vs those of the US, Eurozone, and UK, I expect the overall developed market manufacturing PMI to fall to 54.5 from 56.6 and for the service-sector PMI to fall only slightly to 54.9 from 55.0. These are still figures that show the economy is expanding, but they’re not necessarily moving in the direction you’d want to see at the beginning of a central bank tightening cycle.

Also, Germany’s Ifo index will be released on Friday.

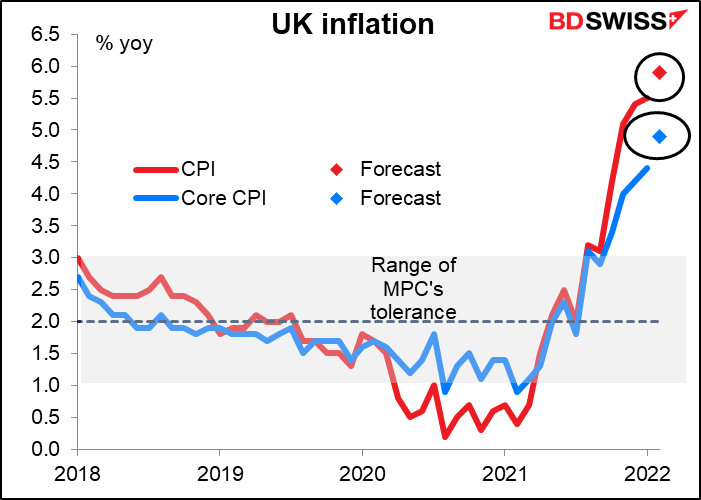

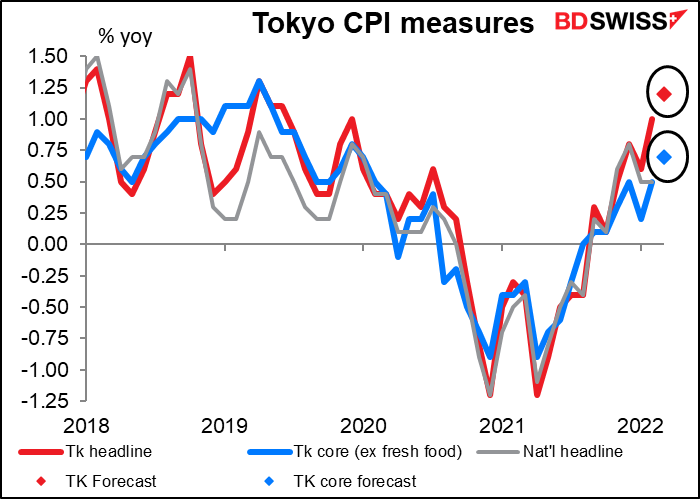

There are two major sets of inflation figures coming out during the week: the UK (Wed) and Tokyo (Fri).

The UK consumer price index is forecast to rise further to 5.9% from 5.4%. This should be no surprise to anyone. The statement following Thursday’s Bank of England meeting said that “Inflation is expected to increase further in coming months, to around 8% in 2022 Q2, and perhaps even higher later this year,” mostly due to higher energy prices. Thus an increase like this shouldn’t shock the markets. It’s likely to be neutral for the pound.

The Tokyo CPI meanwhile is expected to rise further to reach the almost celestial level of 1.2% yoy, which for Japan would be the highest in about two years. But the Japanese-style “core” measure (excluding fresh foods) is forecast to remain below 1% and the “core-core” measure (which in other countries is just plain “core,” excluding food and energy) is forecast to remain in deflation at -0.50% yoy. Imagine – deflation in today’s world! It’s incredible. We’re waiting until April when the impact of the plunge in mobile phone prices falls out of the year-on-year comparison and the annual CPI jumps about 1.5 percentage points.

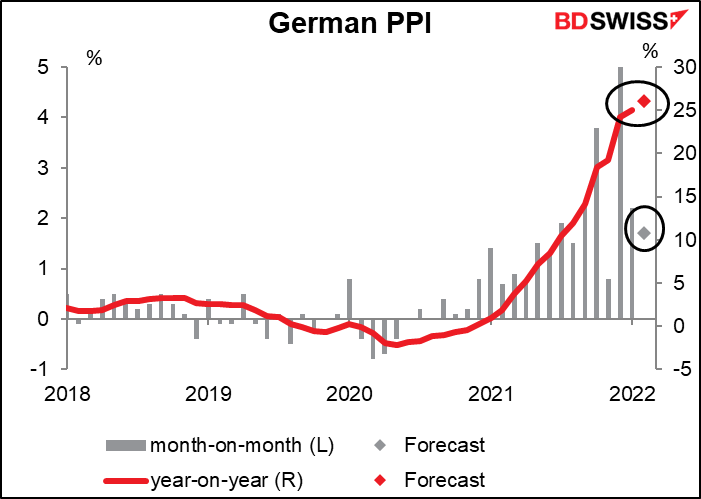

The German producer price index (PPI) also comes out Monday morning. It’s been rising at a fantastic pace – 25% yoy, which is expected to accelerate to 26.1% yoy. That’s bound to feed through to retail prices eventually. Nonetheless there may be some good news in the figures – the mom rate of change is forecast to slow to +1.7% mom from +2.2%

The lesson expected from both these figures is that inflation continues to rise and is likely to keep doing so for some time further. We can expect to see central banks push interest rates still higher as a result.

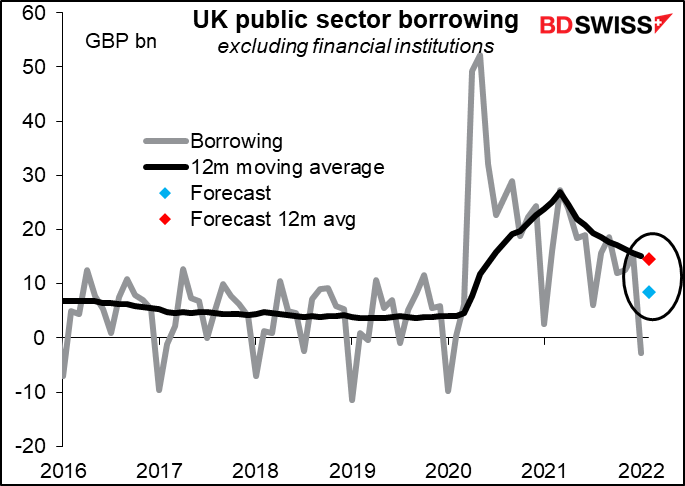

On Wednesday, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak will announce the Spring Statement. The Spring Statement used to be the annual budget announcement, but then-Chancellor Philip Hammond changed that in 2016 and moved the Budget to the autumn, combining it with the Autumn Statement. However, the law still says that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has to produce two forecasts for borrowing and growth every year. So Hammond kept the Spring statement but used it just to announce the OBR forecasts and respond to them. The statement didn’t include any changes in tax or spending.

In the Autumn Budget on Oct. 27th he promised “a new economy post-Covid… fit for a new age of optimism.”. At that time, the OBR forecast the government would borrow GBP 183bn in the fiscal year. But thanks to better-than-expected tax receipts, it’s now expected to borrow only about GBP 160bn. The question then is what to do with the extra GBP 23bn. There’s a good chance he may follow other European countries including France, Ireland and the Netherlands by cutting fuel duty to cushion the blow from soaring energy prices. He may also raise the thresholds before citizens have to pay income tax or national insurance contributions. On the other hand, he’s said to be adamant that the Spring Statement shouldn’t be seen as a full-scale budget and so he may refrain from taking much action at all.

Generally speaking, a tighter monetary policy and a looser fiscal policy are usually a recipe for a stronger currency. Indications that he may loosen fiscal policy could be seen as good for growth and therefore positive for the pound.

Also, the UK public sector borrowing data will be out on Tuesday.

UK retail sales will also be released on Friday.

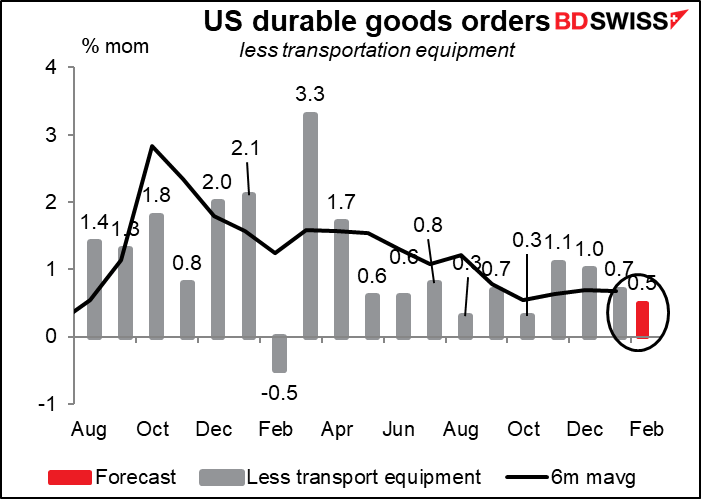

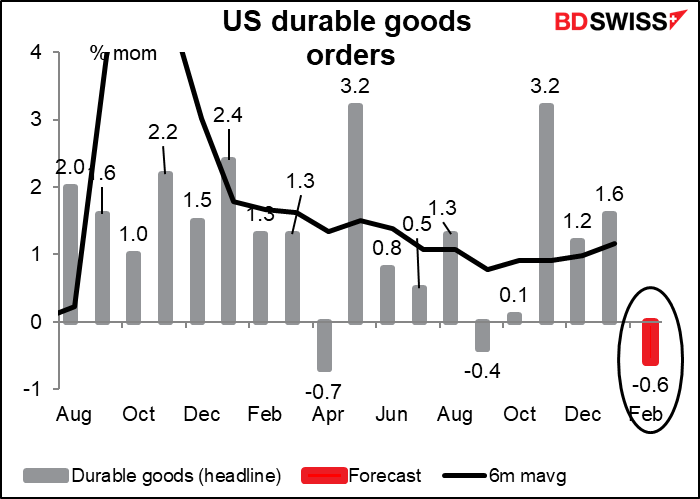

The US will release new home sales on Wednesday and durable goods orders on Thursday.

Durable goods orders are expected to fall from the previous month, but that’s probably due to plane orders.

Excluding transportation equipment, orders are expected to be up +0.5% mom, which would be a bit below trend (+0.7% mom) but not that significant.