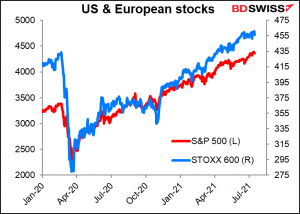

Well, that little dose of panic was short. Last week’s flurry of concern over the worrisome delta variant of the COVID-19 virus didn’t last long. The S&P 500 and the STOXX 600 both hit record highs during the past week, although they pulled back on Thursday…

…while global bond yields declined further despite US inflation soaring far above expectations.

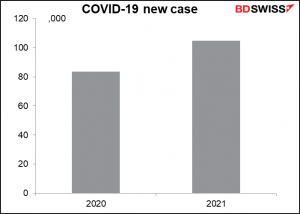

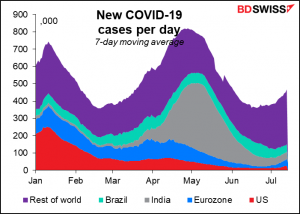

Still, just because the market has for now forgotten about the virus doesn’t mean the virus has forgotten about us. You may not realize it, but globally we’ve had more new cases of the virus so far this year than in all of last year, and this year is barely half over.

And it’s gradually heading up again, everywhere.

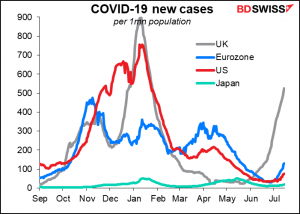

In the developing world certainly, but also in the G10 countries too.

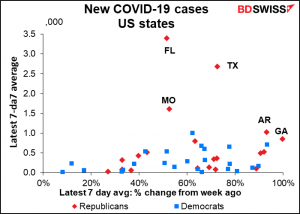

In the US, the numbers aren’t that alarming yet, but the rate of increase in many states certainly is. 50%-100% increases over the last week are common, albeit from a low base in many cases.

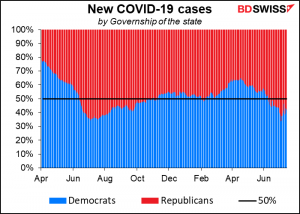

A lot of it is political – many Republicans are still arguing that masks are an infringement of freedom and vaccines are a conspiracy to magnetize people or allow Bill Gates to inject microchips into everyone. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that nearly 47% of residents in counties won by President Biden were fully vaccinated, compared to only 35% of residents in counties that someone else won. The organization noted there is “a widening divide of communities at risk for COVID-19 along partisan lines.”

Fortunately, when people are vaccinated “new cases” are not equal to “deaths.” We may be settling into a chronic situation in the developed countries where many people are getting sick, but not enough to imperil the hospital system. The big problem is in the developing world, where few people have access to vaccines and even when they do, they generally aren’t the more effective vaccines. As long as the virus continues to circulate there, it will mutate and come back to bite everyone. We haven’t heard the last of this story by any means, I’m afraid.

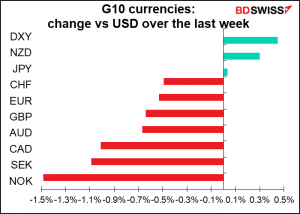

Meanwhile, the other story to watch for is the gradual withdrawal of monetary stimulus. Wednesday the Reserve Bank of New Zealand said it was stopping its quantitative easing program while the Bank of Canada cut its weekly bond purchases by a further CAD 1bn a week. And in Britain, Michael Saunders, an external member of the Monetary Policy Committee, said it may “become appropriate fairly soon to withdraw some of the current monetary stimulus in order to return inflation to the 2% target on a sustained basis” and even outlined what he thought the most appropriate options would be. His comments were notable because he’s been one of the most dovish members of the MPC. MPC member Dave Ramsden made similar comments earlier in the week.

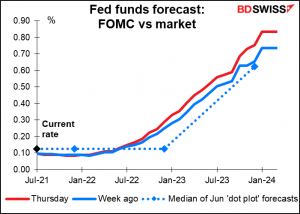

Fed Chair Powell in his testimony to Congress gave no hint that such measures were imminent, but he did say that they’d be discussing tapering down the Fed’s bond purchases at the July 28th meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The market duly brought forward its expectations of how quickly the Fed would raise rates.

The big question then is: what will happen if the virus does intensify, forcing countries to impose further restrictions, while central banks are in the process of withdrawing their stimulus? I don’t like to think about that one.

This week: ECB meeting, preliminary PMIs

This week would be a good one to go to the beach, especially if you live in Japan, where Thursday is “Marine Day,” a national holiday where one is supposed “to give thanks for the ocean’s bounty and to consider the importance of the ocean to Japan as an island nation,” followed by another spurious holiday, “Sports Day,” on Friday, a holiday that usually takes place in October but has been moved up this year to coincide with the opening of the spurious Olympics. Unfortunately for Japanese traders, those are also the only two days with any major announcements scheduled during the week: the meeting of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) on Thursday and the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major economies on Friday.

The ECB meeting was shaping up to be relatively uneventful, but with the release last week of the Bank’s new monetary policy strategy statement, we will get to see how the principles of the new policy play out in practice.

The new policy had the following major changes:

A shift to a symmetric inflation target, with undershoots given equal (or higher) weighing to overshoots The inflation target was previously expressed as “close to, but below, 2%.” Now it’s “two per cent inflation over the medium term” with an explicit commitment to symmetry. “Symmetry means that the Governing Council considers negative and positive deviations from this target as equally undesirable.”

The previous strategy was adopted in 1998 and reviewed in 2003. At that time, many of the countries in the Eurozone had inflation rates well above 2% and the aim of monetary policy was to get inflation down to the target level throughout the region. Now, most countries have inflation below the target. The aim of policy has to change accordingly.

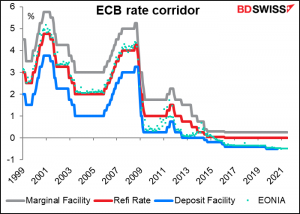

The new policy has a paragraph spelling out the dangers of too low inflation and the need for an “inflation buffer,” which is more important nowadays as interest rates more frequently hit up against the lower bound. I doubt if in 1998 and 2003 anyone was worried about having to implement negative interest rates.

This change is formalizing what they’ve been doing in practice. For example, the last line of the statement following the ECB’s meetings up to now has recently been “The Governing Council stands ready to adjust all of its instruments, as appropriate, to ensure that inflation moves towards its aim in a sustained manner, in line with its commitment to symmetry” (emphasis added). It has merely stated this commitment in more solid terms. However the change does give the doves on the Governing Council additional backing. “The commitment to a symmetric inflation target requires especially forceful or persistent monetary policy action when the economy is close to the effective lower bound, to avoid negative deviations from the inflation target becoming entrenched,” the ECB said in its overview to the new strategy.

The new policy also has room for overshoots, in contrast to the old policy, which tried to keep inflation below 2%. “The Governing Council confirms the medium-term orientation of its monetary policy strategy. This allows for inevitable short-term deviations of inflation from the target, as well as lags and uncertainty in the transmission of monetary policy to the economy and to inflation,” the policy states. This does not go as far as the Fed did with its “average inflation targeting” regime that aims for an overshoot to make up for a period of undershoot, but nonetheless it removes the 2% cap on inflation.

This combination arguably gives more weight than before to supporting other EU economic objectives, such as balanced growth and full employment. This becomes evident from the Overview that the ECB published along with the new statement to explain it and give the rationale behind the changes. It discusses the advantages of taking a medium-term outlook on prices, which it says will help the Bank “to avoid pronounced falls in economic activity and employment” in the case of adverse supply shocks.

Adding financial conditions to the basis for making policy decisions. Before, the monetary policy decisions were based on two “pillars:” the economic analysis and the monetary analysis. The monetary analysis has fallen out of favor in recent years as the link between money supply growth and inflation has diminished. The pillars are now described as “the economic analysis and the monetary and financial analysis.”

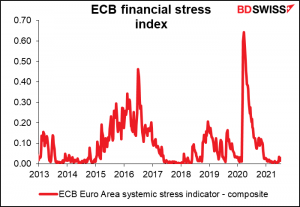

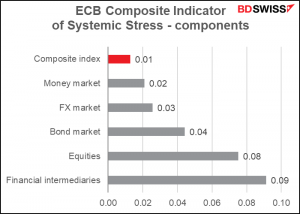

What does this mean in practice? “The monetary and financial analysis examines monetary and financial indicators, with a focus on the operation of the monetary transmission mechanism and the possible risks to medium-term price stability from financial imbalances and monetary factors.” This means more discussion of the transmission of ECB policy to bank lending, side effects of negative interest rates, and imbalances in finance. We will probably start getting more discussion of financial conditions in the statement following the ECB meetings. This may include references to the ECB’s own Composite Systemic Stress Indicator, or perhaps they will adopt a new indicator.

The composite systemic stress indicator aims to represent the level of systemic stress in the Eurozone’s financial system. It’s calculated using 15 mainly market-based financial stress measures from the financial intermediaries sector, money markets, equity markets, bond markets and foreign exchange markets. All components carry equal weightings, which enables it to place relatively more weight on situations in which several markets are stressed at the same time. These series are adjusted to fall between 0 and 1. The higher the number, the higher the stress level.

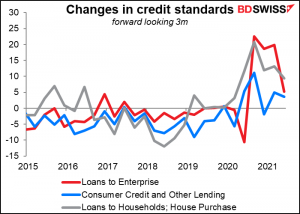

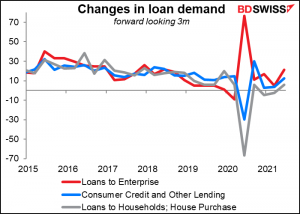

Or perhaps the quarterly Eurozone Bank Lending Survey, due out on Tuesday, may become a more important indicator. It presents a diffusion index (DI) that shows what percent of banks are tightening their credit standards vs loosening them, or seeing higher loan demand vs lower demand, etc.

Adding housing to the inflation data

The new policy retains the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) as “the appropriate price measure for assessing the achievement of the price stability objective.” However, they noted that including the cost of owner-occupied housing “would better represent the inflation rate that is relevant for households.” Accordingly they’ve asked Eurostat to develop a new HICP that includes housing. Since that will take several years, the Governing Council will take housing into account in its monetary policy assessment.

It’s estimated that adding housing will boost the annual inflation rate by 20-30 bps. This will to some degree offset the room for overshoots that was mentioned above. However this is several years down the road since it’ll take some time to develop the new HICP.

Adding climate change to its policy goals

“Climate change has profound implications for price stability through its impact on the structure and cyclical dynamics of the economy and the financial system,” the new statement says. Accordingly, the ECB will begin to take it into account in its decisions. “In addition to the comprehensive incorporation of climate factors in its monetary policy assessments, the Governing Council will adapt the design of its monetary policy operational framework in relation to disclosures, risk assessment, corporate sector asset purchases and the collateral framework.” Concretely that probably means tailoring its bond-buying operations to favor companies that are taking steps to mitigate climate change. Other central banks are taking similar steps.

Updated communication

The statement following the meeting, plus the introduction to the press conference, will be revamped. “These products will be complemented by layered and visualised versions of monetary policy communication geared towards the wider public, which is essential for ensuring public understanding of and trust in the actions of the ECB.”

What this means for the July meeting: Oddly enough, after all this, there probably won’t be much significant change at the July meeting. That’s because the Governing Council probably won’t take any decisions on policy until the Sep. 9th meeting, when the progress of the delta variant will be better known, the path of the economy will be clearer, and new forecasts will be available. Or perhaps they will wait until after the ECB Forum on Sep. 28th & 29th, the annual symposium that’s usually held in Sintra, Portugal. This symposium, like the Fed’s Jackson Hole get-together, has previously been used as a launching pad for new policies. EG in June 2019 then-ECB President Draghi used his speech there to hint at new easing measures. At the July meeting the Governing Council asked the various committees to come up with new easing options, and at the September meeting they cut rates further.

Similarly, when the Fed came up with its new Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy last year, there wasn’t any immediate change in what the Fed did, rather it was mostly confined to what they said.

I expect to see next week:

1) Revamped communications.

The statement following the meeting and the introduction to the press conference will probably read differently. I would expect to see a shorter statement written in simpler language.

2) A change in the forward guidance

As mentioned above, the review concluded that there was a need for “especially forceful or persistent monetary policy action” when rates are at the effective lower bound, as they are now. In an interview with the FT Monday, ECB President Lagarde stressed the need for incorporating this new requirement in the Bank’s forward guidance. “What we will have to do now is redefine our forward guidance to align it with the strategy review,” she said. This may concern what will happen next March, when the Pandemic Asset Purchase Program (PEPP) is scheduled to expire. They may make some pledge about being willing to extend it if necessary or a smooth hand-over from the PEPP to an expanded, more flexible Asset Purchase Program (APP) afterward. What to do when the PEPP is supposed to expire is the big decision that the ECB has to take in Sep/Oct.

3) Formally embedding financing conditions in its assessment of the outlook

We can expect more detailed discussion of financing conditions, as mentioned above, as part of the new “monetary and financial pillar” that replaces the “monetary pillar.”

4) Digital euro preparations

The ECB Wednesday decided to launch “the investigation phase of a digital euro project.” It will last two years and “aim to address key issues regarding design and distribution” of a digital euro. We may get some comments about this.

5) Discussion of climate change and housing costs

These are likely to be features of the summary from now on.

The minutes to the June meeting made it clear that there is a widening gap between the hawks and the doves on the Governing Council, but I don’t expect that to come to the fore at this meeting. The new monetary policy strategy was approved unanimously and so there shouldn’t be much disagreement around it this time. The battle will come in September and October, when they have to decide on the PEPP.

The course of ECB monetary policy is crucial for determining where EUR/USD is headed. So far this year, the pair has closely followed the yield differential between 2-year Bunds and Treasuries. This is a proxy for the relative path of monetary policy between the two, since that’s what dominates in setting short-end yields. If the ECB does indeed take a more dovish turn as a result of this strategy review, it’s likely to result in a weaker EUR vs USD – unless of course the US also takes a more dovish turn too in response to its strategy review. Similarly, EUR could weaken vs GBP too if the consensus on the Bank of England MPC turns.

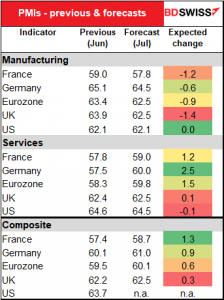

Preliminary PMIs: The other main feature of the week – indeed the only other feature of the week – will be the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) out on Friday (except for Japan, because of the holiday there).

Most countries are in expansionary territory. Compared with three months ago, the expansions have generally been accelerating, except for Japan and India.

The preliminary PMIs are expected to show modest declines in manufacturing, as is natural – PMIs don’t stay high indefinitely. The service-sector PMIs are expected to show further improvement. All told, composite PMIs are forecast to rise, confirming that the global expansion continues. That should be good for the commodity currencies, in my view.