The FX market usually isn’t that volatile this time of year. Companies are slowing down, finishing up for the year and getting ready for Christmas parties, especially British politicians. Hedge funds have already decided on their bonuses – who wants to risk losing a year’s pay on one or two bad trades when there’s no time to recoup losses? And a lot of people are taking off for vacation.

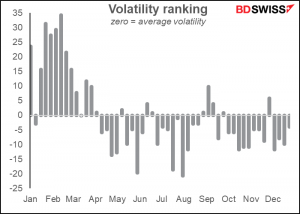

Using the DB FX Vol index, I ranked each week from most volatile (100) to least volatile (0) of the year for 2010-2019 (I didn’t use 2020 as the pandemic distorted the data hat year). I then took the median for each week. If volatility were distributed randomly, over time each week should have a median ranking around 50. The graph shows the divergence from 50. Weeks with positive bars have been more volatile than average, those with negative bars are less volatile.

Note that December is not the least volatile period – that’s usually the summer, when many people are on vacation. Perhaps it’s because central bankers are also on vacation in the summer, whereas they’re still at work this time of year – with a vengeance, as we’ll soon see.

I should add too that this graph only shows the median for the 10 years, which may hide a wide range. For this week, the third-to-last week of the year, one year (2014) it was the third-most-volatile week and one year (2012) it was the least volatile week. So you never know for sure, even if you have a good idea which way the odds lie.

We could be in for more volatility than usual next week thanks to an astonishing five meetings of G10 central banks: the US Federal Reserve, the Swiss National Bank, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan. I guess they all want to get it out of the way so they can enjoy their year-end holiday!

That’s not the only thing on the schedule. There are a large number of important indicators coming out too, including. Japan’s tankan, retail sales from the US, UK, and China, CPI data from the UK and Canada, employment data from the UK and Australia, and the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices from the major industrial economies. Whew! A busy week ahead.

For reasons of space, I’m just going to discuss the central bank meetings, which in any case are inevitably the main focus for the markets.

US Fed: what pace for the tapering?

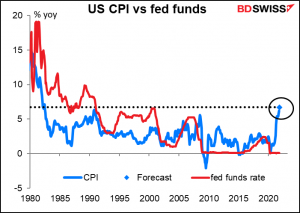

At its last meeting in November, the rate-setting US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to reduce its monthly bond purchases of $120bn a month by $15bn each month. Since then, inflation has soared far above their 2% target and the labor market has continued to improve, putting them nearer and nearer to their goal of “stable prices” and “maximum employment.” In fact if anything prices are unstable now and have to be reined in.

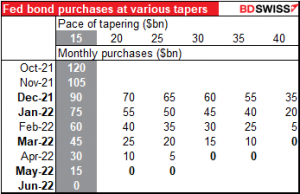

The Committee has already said that it wouldn’t start raising rates until it had ended its bond purchases on the grounds that it would be unreasonable to take accommodation away with one hand while still delivering it with the other. At the current pace, that would mean June would be the earliest possible date for “lift-off.”

As inflation hits levels not seen since the early 1980s – when the fed funds rate was 13%, not zero as it is now – inflation is becoming a sore point among US citizens. The FOMC will therefore debate speeding up its tapering process so they can finish earlier and start hiking rates earlier.

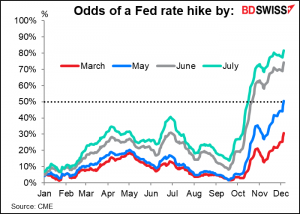

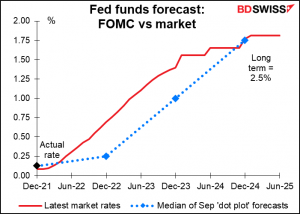

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) derives probabilities of a rate hike from the fed funds futures contracts. As the graph shows, starting in September the market began discounting a rate hike in June or July. Recently though the odds of a hike at the May meeting have risen to better than 50-50, and the odds of a hike as early as March are increasing too. Either of those months would require the Fed to taper its bond purchases at a faster pace.

Looking at the numbers – and what various Fed officials have said – it looks likely that they’ll agree do to so. While the recent US nonfarm payrolls were disappointing relative to expectations (+210k vs +550k expected), +210k is still more than 60% of the months over the last 30 years. Furthermore, the unemployment rate of 4.2% is historically low.

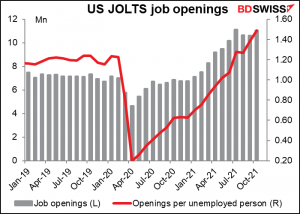

Maybe the unemployment rate isn’t as low as the 3.5% immediately before the pandemic hit, but with job openings much higher, there are a record 1.46 jobs available for every unemployed person. The reason there weren’t more jobs added is probably because people don’t want to work, at least not at the jobs and salaries on offer. In which case, the country is near the Fed’s goal of “maximum employment.”

What’s the likely market impact? It depends on the new pace at which they taper. At the current pace of $15bn a month, they’ll do their last purchases in May and will be able to lift rates at the June meeting (grey column). Raising it to $20bn or $25bn a month would enable them to end their purchases in April and start hiking in May. To hike by the March meeting though they’d have to cut down their purchases by $40bn a month, which might be a stretch at one meeting, particularly with the Omicron variant hanging over the proceedings. I think they’re likely to increase the pace to $25bn a month. That would allow them to hike at the May meeting and leave them leeway to increase the pace once more in a future meeting to finish up in time to hike in March if they want to. If anything, I think a faster pace – say doubling it to $30bn a month as former NY Fed President William Dudley recently urged – is more likely.

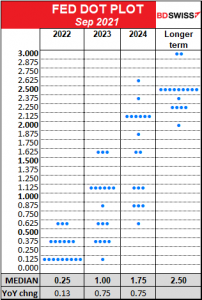

The other focus of attention will be the dreaded dot plot, in which each Committee member says where he or she thinks the fed funds rate is likely to be at the end of the year.

Right now the market is ahead of the Fed in the early years, but in line at end-2024. I would expect the Fed to come more into line with the market’s way of thinking. Such an upgrade in estimates could be positive for the dollar.

ECB: It’s complicated

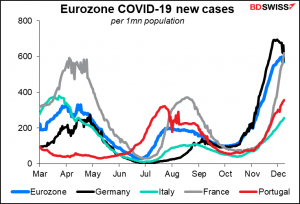

The European Central Bank (ECB) decision is much more complicated. The ECB’s monetary policy has more moving parts that have to be adjusted. Furthermore, the recent sharp increase in COVID-19 cases in several EU countries, exacerbated now by the emergence of the Omicron variant, has added uncertainty into the mix. Even Portugal, which has one of the highest vaccination rates in the world (87%), is seeing an increasing number of cases.

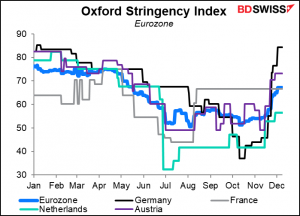

As a result, some countries in the Eurozone are introducing restrictions that will probably act as a brake on business during the crucial run-up to Christmas. That makes the decision to withdraw stimulus more difficult.

Nonetheless, on the assumption that the Governing Council thinks this wave probably won’t be any worse than previous ones, at the December meeting I would expect them to:

- Announce that the EUR 1.85tn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) will be wound up on schedule at the end of March. The Governing Council has said it will end the PEPP “once it judges that the COVID-19 crisis phase is over, but in any case not before the end of March 2022.” The Omicron variant has thrown a wrench in this timetable – will they be able to say for sure that the crisis phase will be over in March? – so I would expect them to hedge their determination somewhat.

- At the same time, increase the pace of purchases until then because of the risks to growth from the Omicron variant

Other topics that they could discuss and previously might have decided at this meeting but now are more likely to leave until March include

- Increasing and perhaps adding some flexibility to the Asset Purchase Program (APP) so that it can take over from the PEPP after the latter has ended. Currently, there are various restrictions on how it has to spread its purchases among the various Eurozone national bond markets and how much of any one bond issue it can buy (if you’re interested in the details, you can find them ) This can cause problems if a country is particularly hard-hit by the pandemic or if its bond spreads start to blow out and the ECB is already at its purchase limits. Whether to increase the size of the APP and how much to allow it to deviate from its current guidelines is a big bone of contention between the hawks (who favor a smaller amount more strictly regulated) and the doves (who want a bigger amount with more flexibility). The APP currently buys about EUR 20bn a month; it’s likely to stay there for the time being.

- What to do about the third targeted longer-term refinancing operation (TLTRO3).

One point that complicates the ECB’s decision is that up to now, the impact of the virus has been largely to slow economic activity. The natural response was therefore to increase the central bank’s support for the economy. Now however further waves of the virus may also have the effect of increasing inflationary pressures by exacerbating strains on the supply chain. That changes how the central bank should respond to further waves.

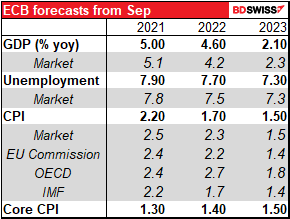

Much will depend on what the new staff forecasts are. Will they continue to see inflation falling back below the 2% target next year? If so, then the Council will probably have to keep an accommodative policy for the time being. That seems like the most likely result. However, several other forecasters see inflation staying above the 2% target next year, which could give the hawks some ammunition.

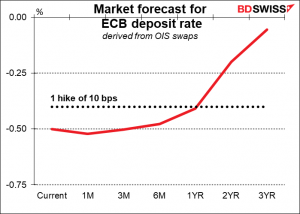

I would also expect ECB President Lagarde to continue to push back against the current market pricing of the first rate hike coming in about a year.

Before the Omicron variant showed up, the December meeting was expected to be another step toward policy normalization. The difference is that now the ECB will probably want to retain more flexibility, given the uncertainties that Omicron injects into the economy. The meeting will therefore be more dovish than it otherwise would’ve been. That’s likely to be negative for the euro.

Bank of England: Similar to the ECB

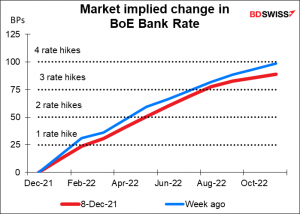

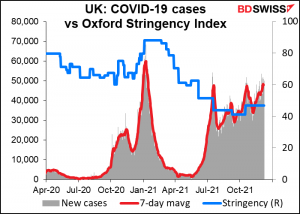

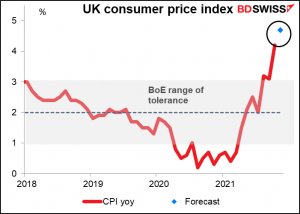

Something similar could be said about the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting. A few days ago, many people in the market were looking for a 15 bps hike at this meeting to bring the Bank’s base rate up to 0.25%. That’s because inflation is well outside their target range and the labor market, which the MPC has said is the key to the outlook, has continued to improve despite the end of the government’s job furlough scheme in September.

Recently however those views have changed. The market has pushed out its expected date for “lift-off” to the February meeting.

With virus cases rising and the Government instituting “Plan B,” a new series of measures to restrict gatherings, it just wouldn’t do for the Bank to pile on the pressure right now. Plan “B” includes work-from-home guidance that will deal yet another blow to central city businesses and weaken the already-weakening growth. We can look to the experience of other central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Reserve Bank of Australia, which have had had to temporarily shelve their normalization plans in response to similar actions by their governments.

As MPC member Michael Saunders – described by one commentator as an “arch-hawk” –said last week, “…given the new omicron Covid variant has only been detected quite recently, there could be particular advantages in waiting to see more evidence on its possible effects on public health outcomes and hence on the economy.” “Could be particular advantages” is typical British understatement for “we better.”

Similarly, Deputy Gov. Ben Broadbent Monday said the question of what the Bank would do about interest rates “is simply not answerable.” Hmmm…that wasn’t their view as recently as the Nov. 4th meeting, when they said (as usual) that assuming everything goes as they expect, “it will be necessary over coming months to increase Bank Rate…”

However, as the graph above shows, the expected tightening has only been pushed out, not cancelled. The MPC will get new employment data on Tuesday and consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday. The unemployment rate is expected to fall further (no forecast available yet for change in employment).

And the CPI, already far above the Bank’s 1%-3% range of tolerance, is expected to rise further. Really, were it not for the virus and the new lockdown measures, a hike in rates at this meeting would be as sure a thing as exists in finance.

The question is, how will the statement and the forward guidance reflect these new data points vs the lockdown measures? If, as I expect, they retain their tightening bias but simply say something along the lines of what Mr. Saunders said, then I think the pound could rally following the meeting. It’s taken a fairly big hit recently, moving down from a recent peak of 1.337 to as low as 1.3163. The MPC reaffirming that rates will indeed go up sooner or later might bolster the currency.

SNB: A change in tune?

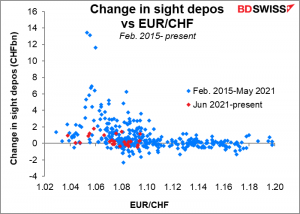

Usually I don’t pay that much attention to the quarterly Swiss National Bank (SNB) meetings. They’ve kept their policy rate unchanged since 2015 and the statements following their meetings seem to be exactly the same, just with the date changed. Their usual bit says:

(The SNB) is keeping the SNB policy rate and interest on sight deposits at the SNB at −0.75%, and remains willing to intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary, in order to counter upward pressure on the Swiss franc. In so doing, it takes the overall currency situation into consideration. The Swiss franc remains highly valued.

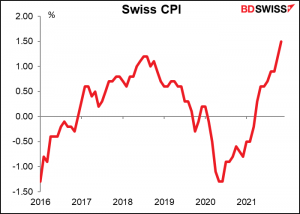

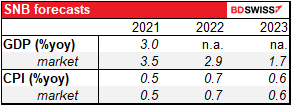

There’s no doubt that the Swiss franc remains highly valued, but there are some doubts about the SNB’s willingness to intervene in the FX market. As the graph below shows, they’ve intervened significantly less this year at each level of EUR/CHF than in previous years.

Perhaps they’re happy with the return of inflation to 1.5% — although some of us would argue that given the preternaturally high price level in Switzerland, the country needs serious deflation, not inflation.

The current inflation rate of 1.5% is much higher than the forecasts, both official and market (they’re the same – this is not a mistake). Maybe having beaten their forecast by so much the SNB is taking a more relaxed view of the FX market. Or perhaps this is their way of going along with the global trend toward normalizing policy. I hope we will get some clarity on the matter from the meeting. SNB President Jordan will hold a press conference afterward so I imagine we will get some answers, although they may not be as clear and forthright as we would hope. (Remember, these are the guys who said back in 2015 that the EUR/CHF floor was “absolutely central” and the “cornerstone” of their monetary policy just days before pulling the rug out from under everyone.)

Bank of Japan: nothing much, as usual

Bank of Japan Policy Board meetings are usually about as interesting as SNB meetings, which is to say, not at all. This time I would expect the SNB meeting to be significantly more interesting than the BoJ meeting.

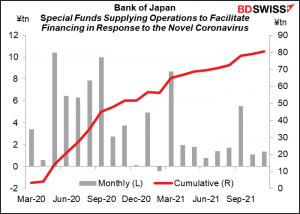

Like the ECB, the BoJ will focus on its program to deal with the pandemic, which is the Special Program to Support Financing in Response to the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). The program was instituted in March last year at the start of the pandemic and like the ECB’s PEPP, is set to expire at the end of March next year. It consists of a) 0% loans to financial institutions and b) increased CP/corporate bond purchasing.

As the graph shows, the facilities haven’t been used that much this year. Accordingly the CP/corporate bond purchasing may be allowed to expire as scheduled, since the BoJ hasn’t been buying them to the full degree allowed anyway. They may extend the loan facilities further just in case the Omicron variant turns out to be more dangerous than expected. I don’t think either move will have major macroeconomic implications, particularly since companies should have no problem raising money in the corporate bond market without the BoJ’s help.

Eventually the BoJ may have to adjust or even lift its “yield curve control” program, which keeps the yield on the benchmark 10-year Japanese Government bond at ±25 bps around zero. However, this meeting probably isn’t the time even as other central banks move to normalize policy. Deputy Gov. Amamiya Wednesday made a speech, Japan’s Economy and Monetary Policy, in which he said,

” I am sometimes asked whether there is no need for Japan to adjust monetary easing while central banks in the United States and Europe have recently started to move toward adjusting theirs. […] Given the price developments in Japan I have described, I think it makes sense that the Bank does not actually need to adjust its large-scale monetary easing at present. Central banks conduct monetary policies in line with developments in economic activities and prices of their respective economies. It is therefore natural that the specifics of and directions for their monetary policies are not the same, and this difference will instead contribute to stability in their economies as well as the global economy.”

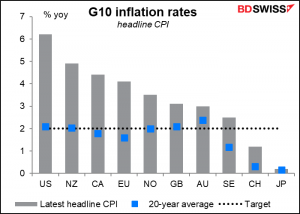

Amamiya isn’t kidding. Japan’s inflation situation is categorically different from that of other countries, even low-inflation Switzerland. Accordingly its monetary policy should be, too.

In short, I think the BoJ is likely to remain on hold while other central banks raise rates and watch their bond markets respond accordingly. The widening yield differential between Japan and other nations is likely to act as a magnet drawing funds out of Japan and weakening the currency.

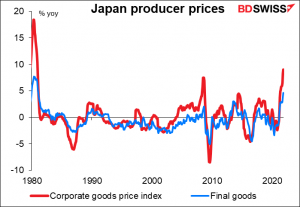

However…It’s possible that change may be in the offing. Japan’s corporate goods price index, known elsewhere in the world as the producer price index, has been soaring. It hit 9.0% yoy recently, the fastest pace of growth since 1980. The final goods PPI rose at the fastest pace since 1981.

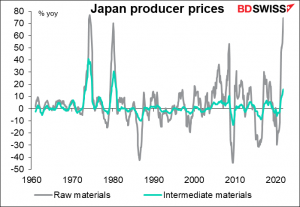

The rise is being driven by higher raw material prices, which are really soaring – up 74.6% yoy!!! That’s the highest rate of growth since the oil shock days of 1974. Intermediate materials were up 15.7% yoy.

I wonder if these higher producer prices will feed through to higher consumer prices. It doesn’t have to happen – companies can absorb the difference in their profit margins – but it could.

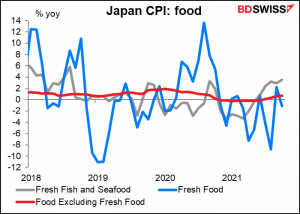

The Financial Times recently had an article saying that rising food prices were starting to become an issue among consumers in Japan. “Some forex traders expect the Bank of Japan will eventually have to respond to the public’s inflation worries,” the story read.

It’s true that food prices globally are rising, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). However, I don’t see it in the data for Japan. The biggest rise I could find in the food items in Bloomberg’s database was fresh fish and seafood, which were up a modest 3.5% yoy in October. Given the variability of prices of such foods, I don’t think this is the stuff of which revolutions are made.

Nonetheless, it looks like we now have to remain vigilant to see if Japan’s low inflation rate, a feature of the global financial markets for decades now, might be finally coming to an end. This could be an unforeseen risk for 2022.

Other events this coming week

I think I’ve gone on long enough here. Usually I’d go through the major indicators, but this week there are so many that it would just be too much for anyone to read. So instead I’ll just leave you with this table of the highlights. Forecasts aren’t yet available for a few of them (e.g. Canadian CPI and US PMIs).