The surprise of the week just ending was the dog that didn’t bark – the muted reaction (no reaction, in fact) to the higher-than-expected US consumer price index (CPI). Everyone was primed for a leap higher in bond yields as the CPI was expected to show inflation leaping over the Fed’s target. In the event it leapt even higher, and yet inflation expectations fell.

If inflation expectations can fall in the face of a 2.6% yoy reading of the CPI, what could change the market’s view on inflation? I suspect it would be not so much a certain level as a “string” of high inflation figures over the next few months (to use the word that Chair Powell used in commenting on the stronger-than-expected nonfarm payroll figures) and gradually people may change their minds. But there are two points to stress:

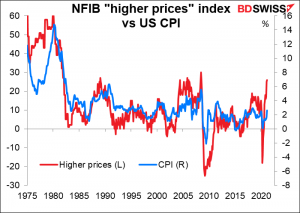

There are any number of past relationships that suggest higher inflation to come. For example, Tuesday’s National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) “higher prices” diffusion index jumped to 25 (% of companies intending to raise prices minus % intending to cut them), a level not seen since 2004-2008, when inflation peaked at 5.6% yoy.

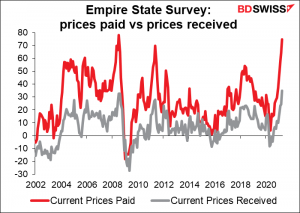

And Thursday’s Empire State manufacturing survey “prices received” index hit a record high while the “prices paid” index was the highest since July 2008 (data back to July 2001).

But as all of us in the financial world well know, “past performance is no guarantee of future performance.” The Fed and, unusually, even The White House have been arguing strongly that “this time is different.” We’ve all learned that this time is never different, but in fact, when was the last time we had a pandemic? 1918? As the article by two members of The President’s Council of Economic Advisors (Pandemic Prices: Assessing Inflation in the Months and Years Ahead) said, “in the next several months we expect measured inflation to increase somewhat, primarily due to three different temporary factors: base effects, supply chain disruptions, and pent-up demand, especially for services. We expect these three factors will likely be transitory, and that their impact should fade over time as the economy recovers from the pandemic.”

Base effects: Prices fell 0.3% mom in March 2020 and -0.7% mom in April. The CPI index itself didn’t regain the pre-pandemic level until July. So the yoy comparison is going to look pretty bad for some time.

Supply chain disruptions: The pandemic has disrupted transportation patterns, causing freight rates to soar. One example: as people stopped traveling, airlines canceled many of their flights. A lot of air freight is carried in passenger planes, but with fewer flights, air freight charges have soared. Meanwhile car rental companies slashed the size of their fleets to match pared-down demand. Now that more people are flying, there aren’t enough cars to meet demand and truck and car rental prices jumped 11.7% mom.

Pent-up demand: The US savings rate has soared – average 29% since the pandemic began, vs 21.5% for the year before the pandemic. Many people have money in their pockets and haven’t eaten dinner in a restaurant in over a year (eg, me for example – well, I’ve eaten outside maybe two or three times). In this week’s Beige Book, the Philadelphia district described demand as “on fire.”

I would add another reason why the headline CPI is rising: higher oil prices. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the gasoline index rose +9.1% mom and accounted “for nearly half of the seasonally adjusted increase in the all-items index.” Oil prices aren’t likely to rise indefinitely, and those base effects will eventually fall out of the calculation too.

Separately, several Fed officials have pointed out that inflation has been low for many many years. There seems to be some structural reason for this — competition from China? Increased globalization? technological improvements? I don’t know. But there’s no reason to think that whatever the factors are that have led to this state of affairs have suddenly gone away.

This view is by no means confined to the Fed. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) this week said that “Some temporary factors are leading to specific near-term price pressures. These factors include disruptions to global supply chains and higher oil prices.” “There will be periods during which inflation will be above the 2 percent target,” it noted. “However, the Committee agreed that medium-term inflation and employment would likely remain below its remit targets in the absence of prolonged monetary stimulus.” The keyword for the RBNZ – as for the Fed and every other central bank, as far as I can tell – is “sustainably.” The RBNZ said it will keep policy in place “until it had confidence that it is sustainably achieving the consumer price inflation and employment objectives.”

The idea is that higher inflation is a “mouse in the snake” event. A bulge appears as the mouse passes through the snake, but gradually it disappears as the mouse gets digested. Similarly, higher prices will appear now as the economy opens up again, but gradually everything will adjust. Airlines will put on more flights, car rental companies will buy more cars, and things will settle back down – or so we’re assured.

It looks like the official explanations have convinced the market, for now at least. The question is how long that will hold up. If six months from now inflation is still over 2%, people’s faith in the transitory nature of these developments may start to waver.

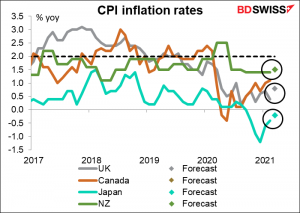

This coming week we’ll get more information on the global inflation picture. New Zealand, Britain, Canada, and Japan release their CPIs. They will allow us to see whether the rise in inflation is specific to the US or general to the world. We also have central bank meetings in Canada and Frankfurt. They will allow us to see if the Fed’s insouciant dismissal of the concerns about rising prices are again specific to the US or more general.

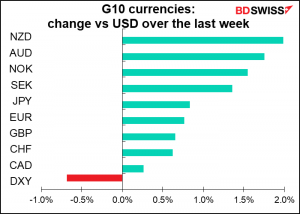

Looking at the CPIs, forecasts are for inflation to move higher in the UK (but remain well below target), inch higher in New Zealand (which issues its data quarterly) and for deflation to lessen somewhat in Japan. (No forecast available for Japan yet.) While these forecasts do imply some upward pressure on prices globally, the pace of increase isn’t likely to alarm the bond vigilantes. Thus, US Treasury yields can probably continue to decline and the dollar weaken further.

The view of central banks on inflation seems to be quite similar.

Like this past week’s RBNZ meeting, I don’t expect anything major from the two central banks that are meeting next week. The authorities are in a holding pattern while they wait to see how the vaccine rollouts go: they’ve made enough progress that they don’t need any further stimulus at this point, but it’s still way too soon to sound the “all clear” and start thinking of withdrawing stimulus.

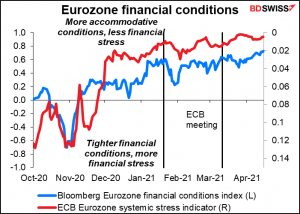

I don’t think anyone expects the ECB to take any decisions. At their last meeting, they agreed to purchase bonds under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) “at a significantly higher pace than during the first months of this year.” They’ll decide whether to maintain that faster pace after a joint assessment of financing conditions and the outlook for inflation at the next Council meeting, on 10 June. So not much to do this time except to assess the situation.

The market will therefore be looking mostly for color and tone from the press conference: which way are they leaning?

The first issue is whether they’re satisfied with the acceleration of purchases in the PEPP. They said they were doing it “with a view to preventing a tightening of financing conditions.” They should be pleased on that front then as financial conditions have relaxed somewhat since the last meeting even though the pace of purchases doesn’t seem to have risen all that much.

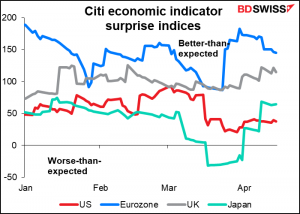

Secondly, we will want to hear their view of the risks to their outlook. Has the recent progress in vaccinations (sketchy though it is) in the Eurozone and the recent better-than-expected data improved their outlook any?

Finally, what’s their take on inflation? Any change in their view – which at their last meeting was in accord with the Fed & the RBNZ as described above – that higher inflation is only temporary?

At their last meeting, they said:

Inflation has picked up over recent months mainly on account of some transitory factors and an increase in energy price inflation. At the same time, underlying price pressures remain subdued in the context of weak demand and significant slack in labour and product markets…the medium-term inflation outlook remains broadly unchanged from the staff projections in December 2020 and below our inflation aim.

Net net, I don’t think the ECB meeting is going to have many implications for the currency and I wouldn’t expect any big moves after it. Of course, if they come out with some surprise – a notably more or less confident outlook, for example – there might be. But I can’t predict that.

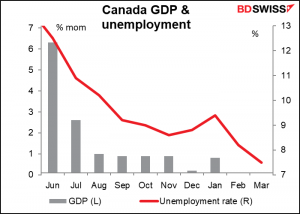

As for the Bank of Canada, things are going well there with the economy. Since the last Bank of Canada meeting, GDP for January was up 0.7% mom, the manufacturing PMI rose to 58.5 from 54.8, and as we saw last week, employment rose a stunning 303k in March with the unemployment rate plunging to 7.5% from 8.2%. (One more month at that growth rate and the number of employed persons will be above where it was before the pandemic hit.) They should be pretty happy with the way things are going economically.

However, it’s too early for them to get optimistic. The problem is that new virus cases have been rising since mid-March. Of course, monetary policy can’t affect that, but it may keep them cautious about the outlook.

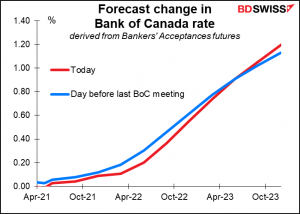

There has been only a slight change in the market’s view of when the Bank of Canada might start hiking rates – maybe pushed back from June of next year to July or August.

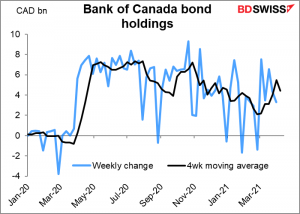

The one area where we might see some change is in the Bank’s bond purchases, which currently run “at least $4 billion per week.” At the March meeting, the statement said that “As the Governing Council continues to gain confidence in the strength of the recovery, the pace of net purchases of Government of Canada bonds will be adjusted as required.” Speculation in the market is that they might reduce this to CAD 3bn or so and extend the weighted-average maturity of their purchases so that they don’t own as much of the short end of the market. That could be taken as the start of tapering and push CAD higher.

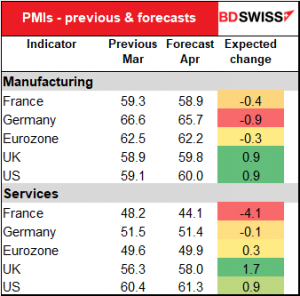

Other indicators out during the week include the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major economies on Friday.

For manufacturing, the Eurozone is expected to fall slightly from the extraordinarily high levels of March, but that probably wouldn’t be significant. On the other hand, the UK and US are expected to rise further.

As usual attention will focus on the service-sector PMIs. Here, the Eurozone is expected to edge up almost – but not quite – into expansionary territory. In contrast, the UK and US, which are already at healthy levels, are expected to show substantial gains. The contrast could be negative for EUR.

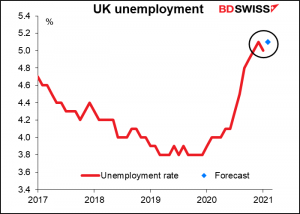

Other important data out during the week include UK employment (Tue) and UK retail sales (Fri). The UK unemployment rate is expected to edge up, which could shake confidence in GBP a bit.