Japan’s Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, resigned suddenly on Friday, citing “ill health.” Having been elected in December 2012, Abe was the country’s longest-serving PM. His sudden resignation came as a surprise to the market. How will his resignation affect the yen?

The initial move was quite predictable. The Tokyo Stock Market fell 0.7% in reaction to the uncertainty, and the yen strengthened, as is typical during “risk-off” situations.

I expect Japanese stocks to remain weak until a new leader is elected and the future economic course becomes clearer. That means the yen could appreciate further for the next two weeks or so. But given the slate of likely candidates, the exigencies of the coronavirus, and the fact that Bank of Japan (BoJ) Gov.Haruhiko Kuroda will remain in office until April 2023, I don’t see much change in the country’s economic situation in the medium term. That suggests USD/JPY should return to its recent trading range after the new PM takes office.

Before PM Abe came into office this time (this was his second time as PM), most Japanese PM held office for a relatively short time. The country had 34 PMs in 67 years, meaning on average they were in office for less than two years. (Naruhiko Higashikuni, the hapless PM immediately after WWII, holds the record at 54 days – less than two months. Three others made it for just two months.)

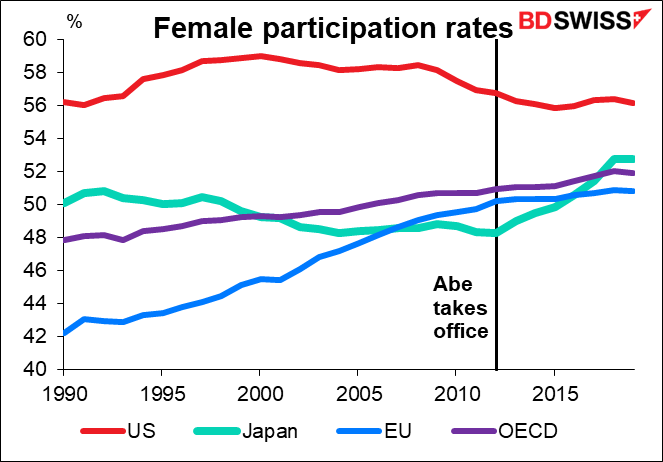

Abe’s nearly eight years in office allowed him to make significant progress with his “Abenomics” economic plan, based on “Three Arrows:” monetary policy easing, an expansionary fiscal policy, and economic reforms to boost growth. Abe had notable achievements in corporate governance, workplace reform, women’s employment, trade liberalization, and increasing immigration and tourism. He failed in his signature goal to rewrite Japan’s pacifist constitution, but failure there is maybe no bad thing.

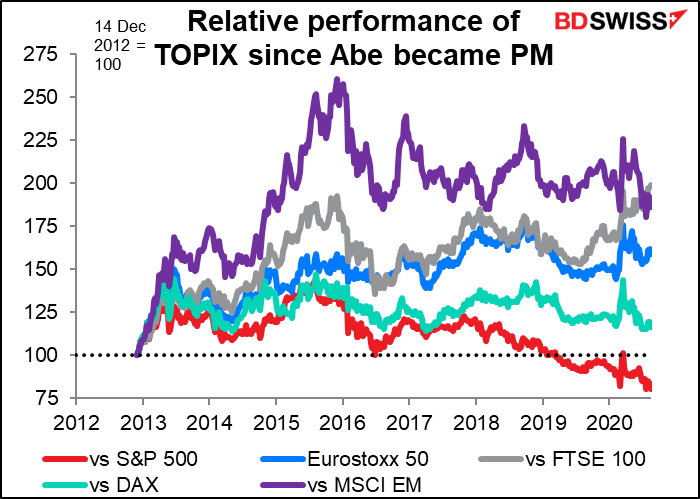

One sign of his success: since he became PM, the Tokyo stock market has significantly outperformed most other major markets in the world, including emerging markets (with the exception of the US stock market).

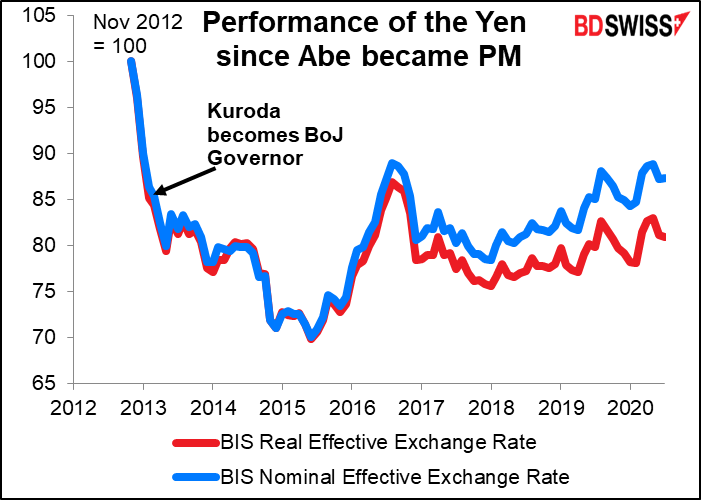

For our purposes, perhaps the most important action Abe took was to appoint the reflationist Haruhiko Kuroda as Governor of the Bank of Japan in March 2013, and then reappoint him in 2018. Gov. Kuroda was appointed to carry out Abe’s “arrow” of monetary loosening, which he did enthusiastically. Under his guidance, the BoJ embarked on a series of unprecedented monetary experiments, culminating in the current “quantitative and qualitative easing with yield curve control.” Since Kuroda became Governor, the yen has weakened 13% in nominal terms and 19% in real terms.

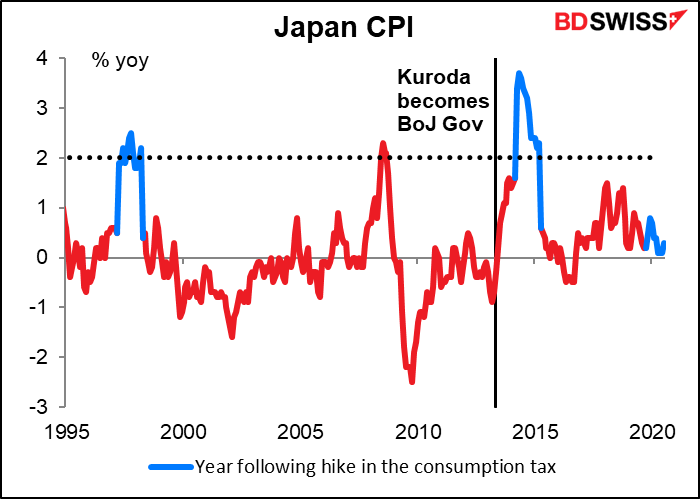

Kuroda had some success in lifting Japan’s inflation rate. Although he has failed to achieve the 2% inflation target, at least the country has managed to escape deflation for most of his term in office, an achievement compared to the decade before.

For the forex market, this is the key point: unless Gov. Kuroda commits career seppuku and resigns along with his boss – which I don’t expect — monetary policy should remain unchanged at least until Gov. Kuroda’s term of office ends in April 2023. The BoJ’s decisions are taken by a vote of the Policy Committee and they are usually 8-1 in favor of the current policy with one member dissenting because he wants an even looser policy. So although the BoJ is of course subject to political pressure, I see little chance of a change in monetary policy any time soon regardless of who becomes the next PM. That should prevent the yen from strengthening too much.

Furthermore, the bureaucrats in the Ministry of Finance remain in place no matter what happens above them, and FX market intervention is hard-coded into their DNA. (See BDSwiss Insights on JPY: The Official Jawboning Begins.) As USD/JPY approaches the Y105 level we’re likely to start hearing more from these folks, limiting the downside for the pair.

In any case, the next PM’s hands will be tied at the beginning by the exigencies of the pandemic. All countries are responding with aggressive fiscal and monetary policy measures at this point in history. Even Germany has started deficit financing! And he is only assured of a year or so in office – the appointment will be for the remainder of Abe’s term, which expires in September 2021.

Over the longer term there could be some changes in economic policy, but for the time being a lot depends on how the new PM is elected. In Japan, the PM is the leader of the ruling party, and the ruling party is (almost) always the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), so the question boils down to, how will the LDP elect its next leader? There are two ways: a poll of the Diet members and prefectural representatives, or those plus a number of rank-and-file LDP supporters. Press reports suggest that because of the pandemic crisis, the party would prefer the former method, which is faster (the rank-and-file members vote by mail, which takes time).

If it’s up to the Diet members, it’s most likely that they’ll elect someone who will continue Abe’s policies. Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga, who has been Abe’s right-hand man for eight years, Sunday said he intends to run for the position on a platform of continuity and stability. If he does throw his hat in the ring, he’s likely to win the position.

There are a number of other contenders for the office – anyone interested in them can read the Reuters round-up. The two other major contenders are LDP policy chief Fumio Kishida and former Defense Minister Shigeru Ishiba, both of whom have already expressed their intention to run. Kishida is said to be Abe’s preferred choice, but there’s a lot of internal LDP politics involved. Ishiba is somewhat different from the other contenders – he’s been a vocal critic of Abe and of the BoJ’s monetary policy – but that’s why precisely why he’s unlikely to win even though he’s the most popular candidate with the general public.

Press reports say the LDP will hold a general council meeting Tuesday to decide how to carry out the election. Assuming it’s the short method, the election will reportedly be held around Sept. 15. The party would then convene an extraordinary Diet session to formally nominate the new leader and PM on 27 Sept. 27.

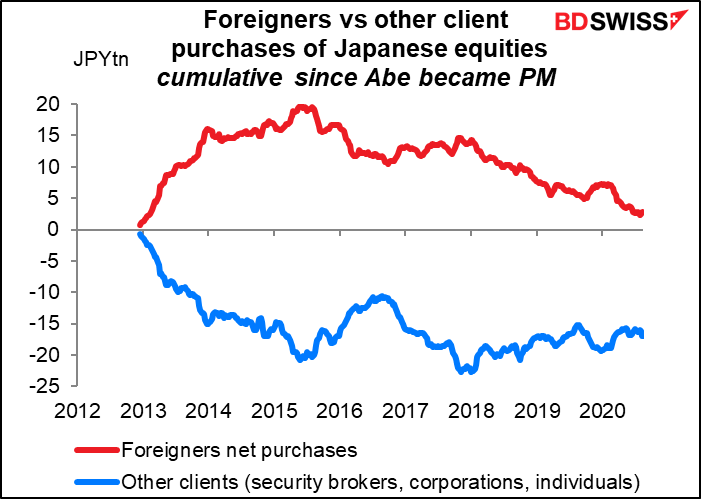

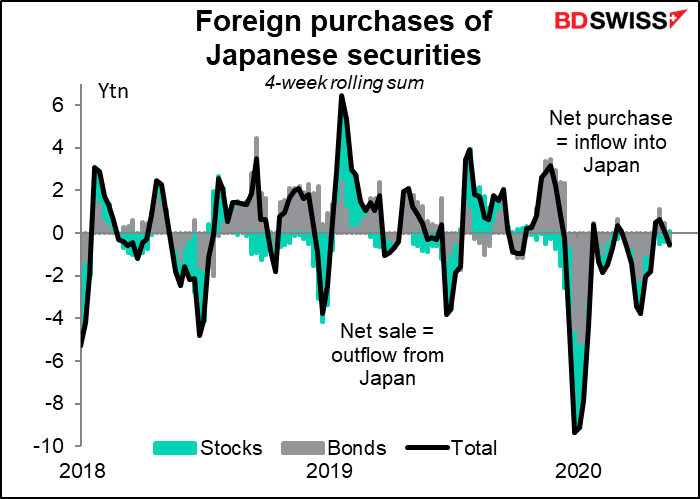

One potential risk for USD/JPY: foreigners were big supporters of PM Abe early on in his tenure, but after realizing the limits of his economic ambition turned net sellers a few years later. If a new PM comes in with new ideas for revitalizing the economy, they could turn buyers again. The foreign inflows into the stock market in 2013 and 2014 didn’t prevent the yen from weakening then, but that was probably because they were countered by Gov. Kuroda’s new ideas for monetary loosening.

Pardon me if I’m cynical, but it’s hard for me to imagine anyone on the current roster of superannuated time-servers acceptable to the LDP Diet members engendering the kind of international enthusiasm that PM Abe did. On the contrary, “more of the same” may accelerate the exit from Japanese stocks, putting upward pressure on USD/JPY (a weaker yen).

But for the time being, the usual risk-aversion and “risk-on, risk-off” dynamic is likely to dominate the yen. Its course therefore probably depends on whether the stock market judges Abe’s eventual replacement to be risky or not.