There’s a lot on the schedule next week: the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of England meet, plus it’s a US nonfarm payroll week. Japan is enjoying the Golden Week holiday.

But the biggest event of all isn’t economic, it’s political: the local UK elections in England, Wales and Scotland. The big issue there is: will Scotland take the first step toward independence? That could be a crucial matter for the pound.

The last time there was a vote on the subject in Scotland, in 2014, the “no” side won 55.3% to 44.7%. But that was before Britain – or, shall I say, England and Wales – voted in 2016 to leave the EU. Scotland voted “remain” 62% to 38%. Since then, the nation has been wondering whether its interests lie more with England, which they’ve been in union with since 1707, or with the much bigger EU.

Pro-independence parties have been pushing for a re-run of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. If these parties win a majority in Thursday’s local election, they may start in motion the actions necessary to take such a vote.

Voting closes at 2200 GMT, but because of the pandemic the counting won’t begin until Friday morning, which means the result is likely to come out over the weekend, when financial markets are closed.

It would take three steps for an independence vote to take place:

1) Pro-independence parties win the election – by no means a sure thing. The Scottish National Party (SNP), which is calling for a referendum before the end of 2023, has been losing support recently and is now below 50% in the most recent polls. It could though win control in a coalition with pro-independence Greens.

2) The UK Parliament would have to grant permission for a new referendum. Unlikely. PM Johnson opposes it, and he has a majority in Parliament.

3) The “leave” side would have to win the referendum, which is also unlikely – they lost in 2014 and recent opinion polls show a plurality (46% to 42%) against independence. But with almost 12% of the voters undecided, it’s still up in the air and a risk to sterling.

Opinion polling “Should Scotland be an independent country?” (% share)

Source: Berenberg Securities

Even if the SNP and other parties in favor of “leave” win Thursday, there are still further hurdles to leap. I think the risk of all three events happening is relatively low. Nonetheless, given the surprise “leave” vote in the 2016 Brexit referendum, we clearly can’t dismiss the possibility. I think Thursday’s vote is a major short-term risk event for sterling.

Wales: The vote in Wales is not as important for now, but it bears watching. Support for independence in Wales is only about 25%, but that’s double what it was a few years ago. The main pro-independence party in Wales, Plaid Cymru, want to hold an independence referendum by 2026 if they are the largest party in the Senedd Cymru – the Welsh Parliament, but recent polling makes this seem unlikely – Labour appears set to be the largest party, even if it doesn’t win a majority of 31 seats.

England: The elections are for local councils and won’t change the balance of power in Parliament. Nonetheless, they are the first real test for both Conservative and Labour since the December 2019 general election. They should give us a good idea whether that election, in which the Conservatives captured a large number of traditional Labour seats, marked a lasting political realignment or just a blip thanks to Brexit. It will also be a measure of the government’s approval rating in handling the pandemic and England’s view of the new Labour Party leader, Keir Starmer. The key will be how the two major parties perform in the traditional Labour heartlands — the Midlands, Yorkshire, North East Wales, and Northern England — where the Conservatives managed to flip most seats.

Luckily, you will note that there is no vote in Northern Ireland. The Northern Irish are not happy at all at the way they’ve been treated – PM Johnson lied to them and wound up creating a trade barrier between the province and the rest of the UK rather than make a “hard border” between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Many

Will the Bank of England do a Canada?

Thursday will be a busy day for Britain. As well as the election, there’s the result of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting, along with an updated Monetary Policy Report (MPR) with new forecasts.

Things have been going the BoE’s way recently in Britain. The inflation rate rose from 0.4% yoy to 0.7% in March and if other countries are any guide, is likely to climb further. Meanwhile the unemployment rate fell to 4.9% in the three months to February from 5% in January (although employment fell by 73k).

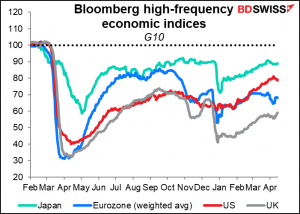

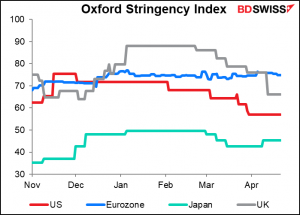

According to Bloomberg’s high-frequency indicators, UK activity took a dive in January, when the economy went into lockdown, but has been recovering steadily since then.

As the lockdown has been relaxed…

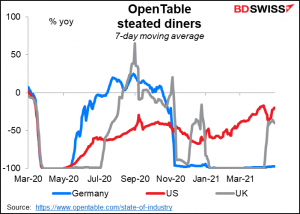

…economic activity has bounced back. For example, more people are going out to eat nowadays.

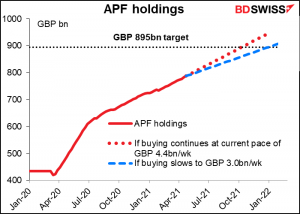

This favorable background is likely to result in a substantial upward revision to the forecasts in the Monetary Policy Review. That could provide the justification for the MPC to follow the Bank of Canada’s footsteps and begin tapering its bond purchases. I expect the Committee to vote unanimously to keep Bank Rate and the total amount of bond purchase unchanged at GBP 895bn but to slow the weekly pace of bond-buying from its current GBP 4.4bn a week to around GBP 3.5bn or GBP 3.0bn. That would allow the Bank to complete its current QE program of GBP 150bn and reach its Asset Purchase Facility (APF) target of GBP 895bn by the end of 2021. Otherwise, they will hit the target around mid-October and either have to stop it then or decide to extend it at a time when the UK economy should be on the mend, according to their forecasts.

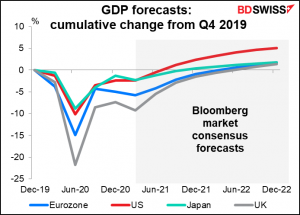

This is despite the fact that on current market forecasts, the UK won’t recover to pre-pandemic levels of output until Q2 2022. In short, the Bank would start the process of withdrawing the extraordinary monetary stimulus instituted to deal with the effects of the pandemic before the economy has recovered entirely. That would be a hawkish move that should support sterling somewhat in the face of political uncertainty.

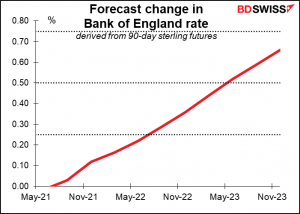

A decision to begin tapering down the bond purchases is not necessarily a decision to begin hiking rates, though. Currently the 3-month sterling market expects the Bank to start raising rates around December, although the overnight index swap (OIS) market has no such hikes priced in at all.

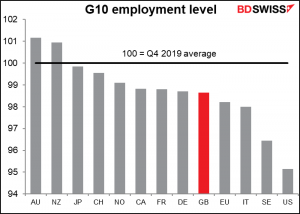

The MPC has stressed that the bar for tightening policy is quite high. Their forward guidance at the March meeting was, “There is judged to be a material degree of spare capacity at present…The Committee does not intend to tighten monetary policy at least until there is clear evidence that significant progress is being made in eliminating spare capacity and achieving the 2% inflation target sustainably.” “Significant progress” like Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s “substantial further progress,” is a long, long way off. Total UK employment is still 1.4% below pre-pandemic levels, and that’s with 4.8mn people on the government’s furlough program. If we were to subtract those people, then employment would be some 16% below pre-pandemic levels. The furlough scheme ends in September. It’s pretty certain that they’ll want to see employment come back up to previous levels and that “spare capacity” in the labor market removed before they start thinking about tightening.

RBA: not much excitement.

In contrast to the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is not likely to have a very exciting meeting. I expect them to leave their policy settings unchanged. Any excitement will arise from the updated forecasts in the quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), which will be released on Friday

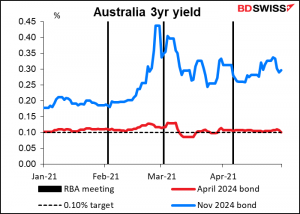

The main decision they have to take is whether to extend the maturity of their yield curve control (YCC) program, which currently aims to keep three-year yields around 0.1%. That would involve switching from the April 2024 bond to the November 2024 bond.

The RBA said after its last meeting (April 6):

The Board remains committed to the 3-year government bond yield target of 10 basis points. Later in the year it will consider whether to retain the April 2024 bond as the target bond or to shift to the next maturity. The initial $100 billion government bond purchase program is almost complete and the second $100 billion program will commence next week. Beyond this, the Bank is prepared to undertake further bond purchases if doing so would assist with progress towards the goals of full employment and inflation

As the graph shows, the market assumes the RBA will not extend the YCC target and therefore the November 2024 bond is not trading in line with the April 2024 bond. As a former bond market analyst, I can’t understand what they’re thinking. If they want to keep targeting three-year yields, they simply have to roll the target bond. The minutes of the meeting explain:

If the Board were to maintain the April 2024 bond as the target bond, rather than move to the next bond, the maturity of the yield target would gradually decline until the bond matured in April 2024. In considering this issue, members would give close attention to the flow of economic data and the outlook for inflation and employment

A decision not to roll the purchase would be in effect a “quasi-taper.” Since it’s the three-year yield that’s used as the benchmark for a lot of Australian financial products, such as mortgages, targeting the yield of an ever-shorter-maturity bond would mean allowing the actual three-year yield to gradually drift higher. This would reduce the impact of the RBA’s YCC program on the economy. It’s a good example of the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu’s saying that “by doing nothing, everything is done,” a Taoist philosophy that I abide by closely when it comes to housekeeping.

Of course, they could also decide just to suspend the entire YCC program. Either way though, I don’t think the next meeting qualifies as “later in the year,” so I don’t expect a decision at this meeting.

The RBA may confirm that its Term Funding Facility will expire at the end of June, but that’s already been flagged.

With no decisions likely, market attention will focus (as I mentioned) on the updated forecasts. The statement following the RBA meeting will summarize those new forecasts.

Given the strong performance of the labor market in Australia – the unemployment rate is already lower than the end-year forecast in February’s SMP and number of jobs is higher than it was before the pandemic – the RBA may decide to revise up its inflation forecasts. Australia seems to be one place where the Phillips Curve, the supposed relationship between employment and inflation, still holds.

If it did that, it could decide to revise its forward guidance as well. It currently says that it doesn’t expect the conditions for raising the cash rate to be met “until 2024 at the earliest.” But again, I think it will delay that decision until later – perhaps until the next SMP in August – to make sure that the improvement is “sustainable,” which seems to be the key word among central banks. Nonetheless the market could start to discount an earlier-than-expected normalization of policy, which would be positive for AUD.

Between Tuesday’s meeting and Friday’s SMP, RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle will speak on Thursday on “Monetary Policy during COVID”.

We may get some additional color about other recent central bank meetings from official speeches. ECB Chief Economist (and rumored shadow President) Lane speaks on Wednesday, and (nominal?) ECB President Lagarde on Friday. In the US Dallas Fed President Kaplan and Cleveland Fed President Mester, both non-voters, both speak twice. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand publishes its Financial Stability Review on Wednesday and RBNZ Gov. Orr will hold a press conference about it.

NFP: Two points don’t make a string

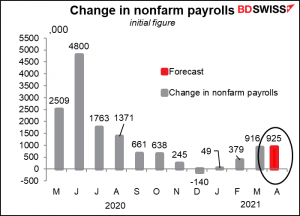

On top of all that, it’s a US nonfarm payrolls (NFP) week. After last month’s stunning 916k increase, well above the market consensus estimate of 660k, economists are expecting an even higher increase of 925k this month, with estimates ranging so far from 700k to 1.25mn.

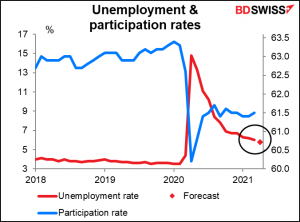

The question the market will be asking is, does another 900k+ jobs number qualify as “substantial further progress” according to the Fed? A few weeks ago, Fed Chair Powell said it would take “a string of months” of numbers like that to qualify. At the press conference following the recent FOMC decision, he was asked, what is a string? He replied, “I can tell you what it’s not. It’s not one really good employment rating…” He once again emphasized that the US is still 8.4mn jobs below its pre-pandemic level, “and that doesn’t account for growth in the labor force and growth in the economy, that trend we were on.” In that respect, the participation rate (no forecast available yet) may begin to be as important an indicator as the NFP number itself, just as average hourly earnings used to be. The participation rate has fallen to 61.5 from 63.4 in January.

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate is expected to fall two notches to 5.8%, an improvement but still far away from the pre-pandemic level of 3.5%.

Oddly enough, there is other evidence that the US labor market is relatively tight. The participation rate may have fallen because people don’t want to work: either they believe it’s unsafe in the current environment, or they are caring for someone who’s sick, or they have to stay home since their children aren’t attending school. On the other hand, there are 5% more jobs available than before the pandemic, according to the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). Anectodtal evidence in the recent Beige Book confirmed the idea that there are now more jobs chasing fewer people.

Notice how after the Lehman Bros. collapse in 2008, the number of job openings (red line) fell by more than half and didn’t recover until 2014. This time around it fell immediately after the pandemic but has since recovered entirely. Meanwhile, the quit rate – the rate at which people voluntarily leave their jobs — has recovered to the pre-pandemic level. Usually, people don’t leave their job unless they’re confident of getting another one, so this is a general indicator of the strength of the job market.

It’s Golden Week in Japan, the week when there are four holidays in five days. It started yesterday, when my daughter, who’s in college in Kyoto, got up for class and discovered there were none that day. She says it’s likely to be pretty miserable this year as there’s a “State of Emergency” (they don’t call it a “lockdown”) in various parts of the country, although the restrictions seem pretty lax to those of us who have to send an SMS to the authorities before we’re allowed out of our houses. This coming week, Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday are national holidays in Japan, as well as in China, where it’s an extended “Labor Day.”. Monday is Labor Day in the UK.

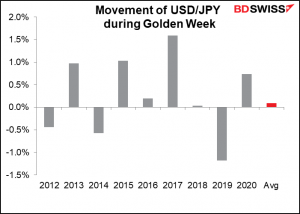

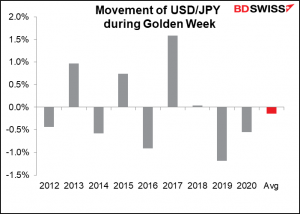

How does USD/JPY generally behave during Golden Week? I looked at it for the last 10 years. It’s hard to define when Golden Week starts & ends, because sometimes the last day is a Wednesday, in which case I assume most people would take Thursday and Friday off and come back the next Monday, so usually I ended the week on a Monday.

The result? No trend at all. USD/JPY was up six times and down four times. On average up 0.1%, which is as good as unchanged.

Taking a stricter approach and counting exactly from the day before Showa Day, the first holiday, to the day after “National Holiday,” the last of the string, we get the opposite result: four ups and six downs, for an average of -0.1%. Again, it’s basically a coin toss. No tradeable pattern.

Other indicators

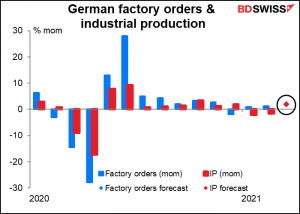

In the EU, we get German factory orders on Thursday and industrial production on Friday. They’re expected to be up 1.8% mom and 2.0% mom, respectively. That’s a respectable increase and would be the first increase in orders in three months, which is positive.

Globally, we get the final manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) on Wednesday and the final service-sector PMIs on Friday for the countries that had provisional ones. As usual, the US Institute of Supply Management (ISM) will announce its version of the PMIs shortly thereafter. The ISM prices paid index will be closely watched for rising inflationary pressures.