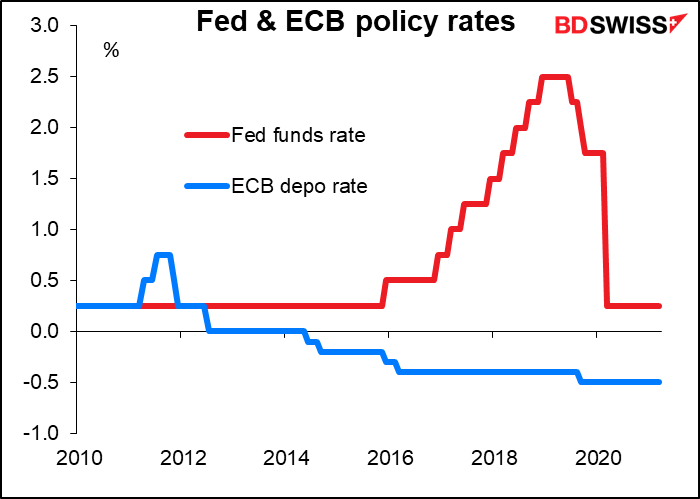

Some time ago, the key phrase in the market was “monetary policy divergence.” Economies were growing at different speeds and central banks were moving to adjust interest rates at different speeds. Most noticeably, the Fed was on a gradual tightening track while the European Central Bank (ECB) was still trying to get back to its inflation target. This divergence of monetary policy was one of the major factors affecting FX rates.

Now with central banks all over the world frozen in place, monetary policy divergence is a thing of the past. The range between the highest policy rate (US, Canada, New Zealand at 0.25%) and the lowest (Switzerland at -0.75%) is 100 bps. This compares with 475 bps at the post-Global Financial Crisis peak.

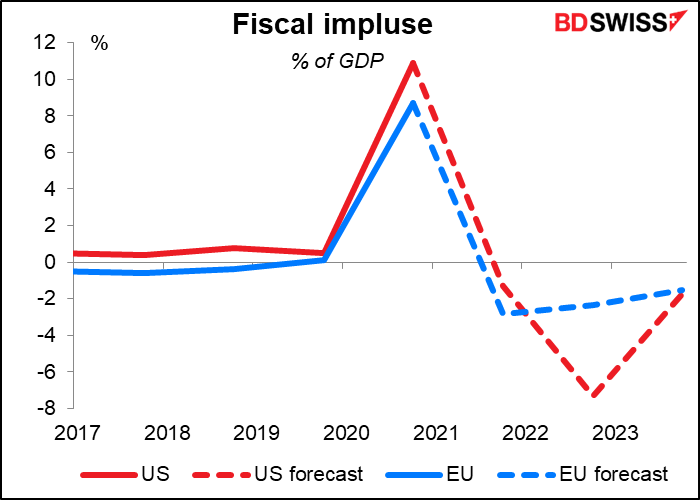

Instead, what we are seeing is fiscal policy divergence. And nowhere is that more evident than in the gap between the US and the EU.

President Biden this past week unveiled an infrastructure spending program estimated at $2tn over eight years. This follows on the heels of a deficit-funded $1.9tn giveaway program. And he’s not done yet: there’s another program aimed at more “family-oriented” measures, such as health care, that’s going to be unveiled in a few weeks.

By contrast, the EU counterpart, the Next Generation EU recovery fund, is MIA (Missing In Action). The European Council agreed on the €750bn fund with much fanfare back in December. It was considered a game-changer because the money would be raised by issuing bonds guaranteed by all EU members, creating the first Euro-wide debt.

But while President Biden announced the $1.9tn American Rescue Plan on Jan. 20th and the checks are already hitting peoples’ bank accounts two months later, no one has seen one euro-cent of the Next Generation money yet, for two reasons. First, so far only 13 of 27 EU member states have ratified the decision. All 27 member states must do so before the EU can start raising funds in the market, and not all are eager to do so. EG the German Constitutional Court has delayed ratification pending an emergency appeal, among other obstacles in other countries.

Secondly, none of the national recovery plans have been published yet. The deadline for submission is April 30th and the plans are supposed to be approved within three months after that (two months for the European Commission, one for the European Council). That means in theory the plans should be approved by the end of July. But of course if the countries can’t meet their deadline for submission, then the approval will be delayed, too.

Hence whereas it was hoped that the money would start to flow by September, it now looks like that’s a “best case” scenario. Some time in Q4 looks more likely – assuming of course that all the countries approve the necessary borrowing power.

A better way of thinking about this is the concept of fiscal impulse. This looks at not the absolute level of the deficit but rather the change in the deficit from one year to the next. The reason is that if one year there’s a budget deficit of 2% of GDP and the next year the deficit is again 2% of GDP, then in fact the deficit is providing no additional stimulus.

Looked at this way, the 2020 fiscal impulse in the US was a positive 10.9% of GDP, vs 8.7% for the EU. In 2021 it’s forecast to be a contraction of 2.9% in the EU, vs a contraction of 1.3% in the US. So more expansionary last year and less contractionary this year.

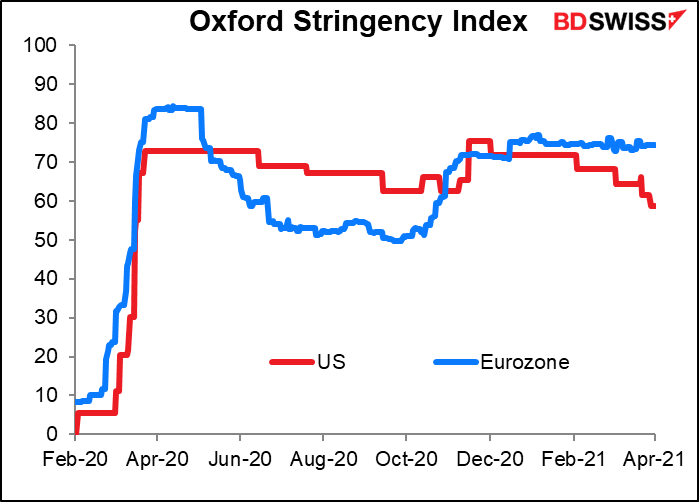

Plus of course there’s the issue of pandemic policy divergence as well. Many countries in the EU have recently gone back into lockdown or intensified their lockdown (France, Germany, Italy), which will weigh on growth for the time being. One hopes that this will simply set the stage for a more robust recovery later, but so far we haven’t seen that – just a cycle of bigger and bigger “waves” of infection. And the way the vaccine rollout is going in Europe, I’m not too optimistic.

By contrast, many states in the US are lifting restrictions – for better or worse, but they’re doing it anyway. Meanwhile the vaccine rollout is going much better than anyone had hoped. The US may well see yet another, even bigger “wave” of infections, but (Republican) governors of many states seem willing to make the trade-off of more infections & deaths in exchange for less interference with the economy.

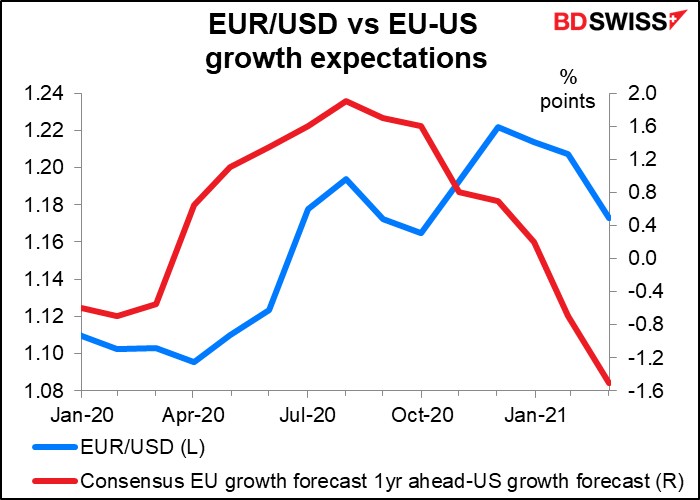

The key point here being that growth differentials – or expected growth differentials – often play an important part in determining the course of EUR/USD.

In short: I’m getting nervous about my bearish USD view. While I expect that the Fed will indeed keep interest rates lower for longer than the market is currently expecting, that’s not the only thing that determines FX rates.

Next week: calm again

Next week is yet another holiday week as Monday is Easter Monday in many of the same countries that celebrate Good Friday. Not the US but in many other Western countries. Furthermore, since the first week of the month had so few days in it, the second week is missing what’s usually the most important indicator of the week, the US consumer price index. As a result, we have few important indicators.

There’s likely to be some interest around the International Monetary Fund (IMF)/ World Bank annual Spring meetings will start on Monday and run until Saturday. They’ll all be held virtually this time, rather than the usual gathering in Washington, where the cherry blossoms are already in full bloom (in Japan it’s the earliest they’ve bloomed in 1,200 years). Since they’re being held virtually you can watch some of the proceedings if you want on IMF Live or World Bank Live. You can see the whole schedule here. (I confess, I haven’t finished watching Season 4 of Lucifer yet and I’ve just started Lupin, so I’ll probably give it a miss.)

Tuesday the IMF will release its new World Economic Outlook – that sometimes causes a “risk-on” or “risk-off” flurry, depending on whether they upgrade or downgrade their forecasts. This time I’d expect an upgrade, which could be positive for AUD. And Fed Chair Powell will participate in a Debate on the Global Economy on Thursday. (My guess: he’s in favor of it.)

The Fed releases the minutes of its March 17 meeting on Wednesday and the ECB publishes an account of its March 10-11 Policy Meeting on Thursday.

For the Fed, the meeting didn’t make any major (or even minor) change in policy. What was notable was that they upgraded their economic forecasts but the median forecast for fed funds was unchanged at its current level at end-2023. We will be interested in hearing more about their reasoning on this matter, as well as the other side of the argument from the two additional members who penciled in higher rates then (seven vs five in December). I’d particularly like to hear the reasoning of the two people who expect fed funds to hit 1.25% then.

As for the ECB, that was the meeting when they announced they would significantly increase the pace of purchases by the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) until the end of Q2, after which they would reassess the pace. President Lagarde implied at the press conference that this reassessment would take place every quarter when new staff projections were available. That created a “tapering risk” at those meetings. But later she and others clarified that they could reassess purchases at other meetings if conditions warrant it. The market will want to know more about the discussions on this issue and in particular what change in conditions might warrant a tapering of PEPP purchases without a change in forecasts.

The two things to watch for at the meeting are a) the RBA’s assessment of labor market conditions, and b) what they think of the housing market.

Back in December, the Board said reducing unemployment was ”an important national priority.” Since then they said they’d need to see “significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market” before they could think of normalizing policy. But when the unemployment rate hit 5.8% in February, that meant it was already below the RBA’s end-year forecast of 6% as set out in the February Statement on Monetary Policy, while the participation rate has recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Of course Australia is still far away from their estimate of full employment, which seems to be around 4 ¾%, but nonetheless they are seeing much faster progress than expected.

It will be interesting to hear what they have to say about employment, particularly with regards to the risks as the JobKeeper Payment Scheme, which subsidized keeping people in work, finished at the end of March.

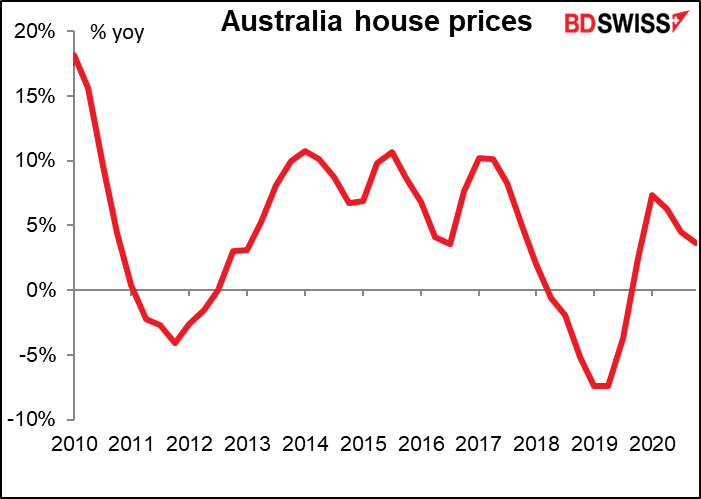

Housing market conditions may also feature more prominently in the statement following the meeting, not because of any general national concerns (like in New Zealand) but rather because this meeting will see the publication of the semi-annual Financial Stability Review (FSR) on Friday. The Board will have been briefed on the key findings of the FSR and those findings are usually summarized in the statement. They will probably talk about “watching” the housing market but I doubt if they’ll express any overt concern.

As for the indicators, the final service sector purchasing managers’ indices are coming out for those countries that have preliminaries and the one-and-only versions for the others. Because of the holiday, the US will be released on Monday and the EU on Wednesday.

German factory orders for February come out on Thursday and industrial production on Friday, a key indicator of output for the EU. Both are expected to rise on a mom basis and show some acceleration on a yoy basis. This could augur well for output in the EU.

Of course, with the German manufacturing PMI at the record high of 66.6 in March “with goods producers reporting the steepest rises in new orders and output since the survey began in 1996,” as Markit said, investors probably won’t pay that much attention to the February figure as it’s March we’re waiting to see.

There was some worrying news in the survey about inflation – or maybe encouraging news, depending on your point of view. According to Markit:

The survey found that 76% of manufacturers had seen average supplier delivery times lengthen in March, which was new a record for the series and up from the previous high of 64% in February. Delays often arose due to demand for raw materials and components outstripping availability, with electronics, plastics and steel among the items most commonly reported as in short supply. A dearth of shipping containers remained a factor. Higher prices for commodities and other inputs ensued, with the rate of cost inflation accelerating sharply to the second-highest on record (behind that seen in February 2011).

The combination of rising costs and strong demand led to a steeper rise in factory gate prices in March. The rate of inflation on this front was in fact the quickest since this series began in September 2002.

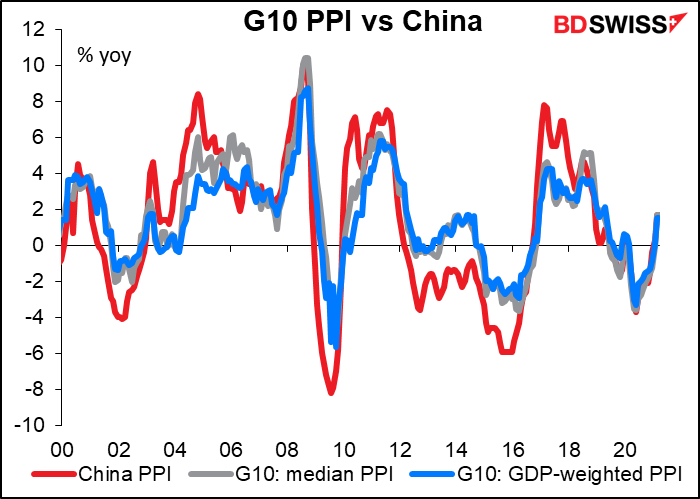

This perhaps explains why China’s producer price index, due out Friday, is expected to jump so much. This would be the biggest jump in the yoy rate of increase in producer prices since December 2016.

China’s PPI is of more than just academic interest to the world. China’s producer prices are everyone else’s import prices. As the graph shows, the general trend of producer prices in the major industrial countries tends to move along with “the China price.” I don’t know whether this is causation – higher (or lower) China PPI causing higher (or lower) producer prices elsewhere – or correlation — all the countries independently following the same external factor, which in this case would probably be global economic demand. It could well be that as manufacturing recovers around the world, all manufacturing is subject to the same sorts of upward pressure on prices that Markit described in Germany.

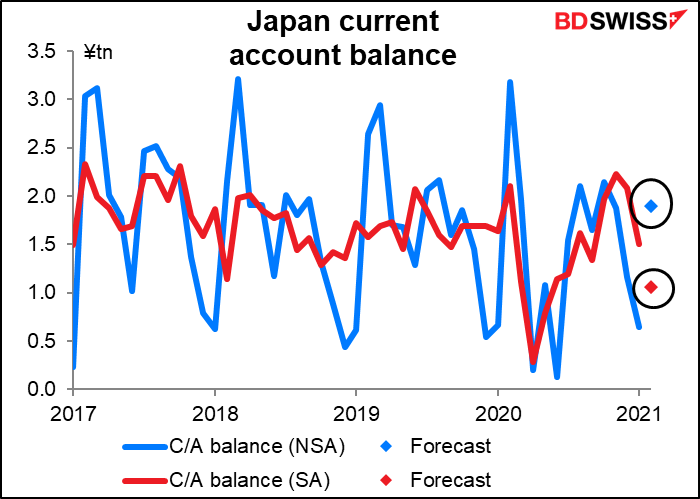

Japan’s current account surplus is expected to decline on a SA basis, although that would be a sharp rise on an NSA basis. In any case the figure for February is notoriously volatile because of the Lunar New Year, which affects exports to China and Taiwan.

Canada’s employment data will be released on Friday. No forecast available yet.