It was 50 years ago today that Nixon met at Camp David with Fed Chair Arthur Burns, incoming Treasury Secretary John Connally, and then Undersecretary for International Monetary Affairs (and future Fed Chair) Paul Volcker and decided to close the gold window, thus ending the Bretton Woods system of exchange rate management.

Nixon went on TV on Sunday while financial markets were closed and announced that “I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets, except in amounts and conditions determined to be in the interest of monetary stability and in the best interests of the United States.” That “temporary” action has proved to be quite long-lasting!

The “Nixon Shock” permanently altered the global financial system. Nixon gave countries their monetary sovereignty. With the ending of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, a system of individual currency management practices previously unknown except during wartime has now become embedded in the global financial landscape.

If you’re interested in the history of that decision, what led up to it and how it was made, you can read the history of it on the Fed’s website.

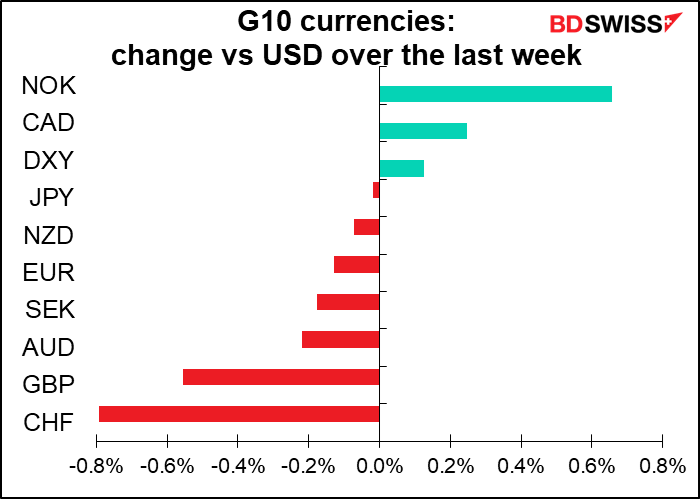

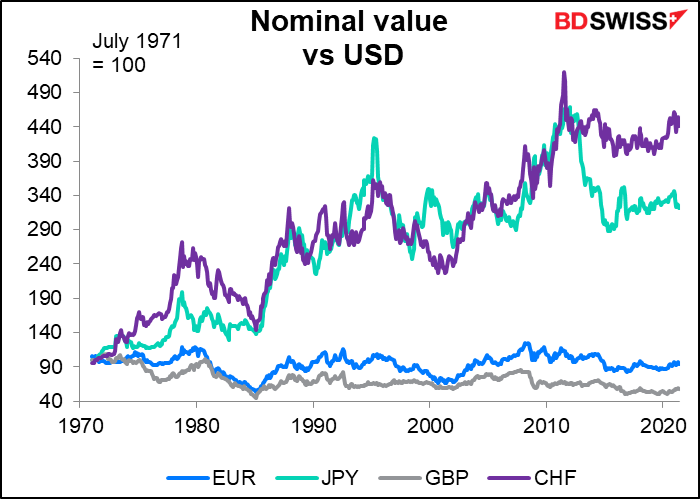

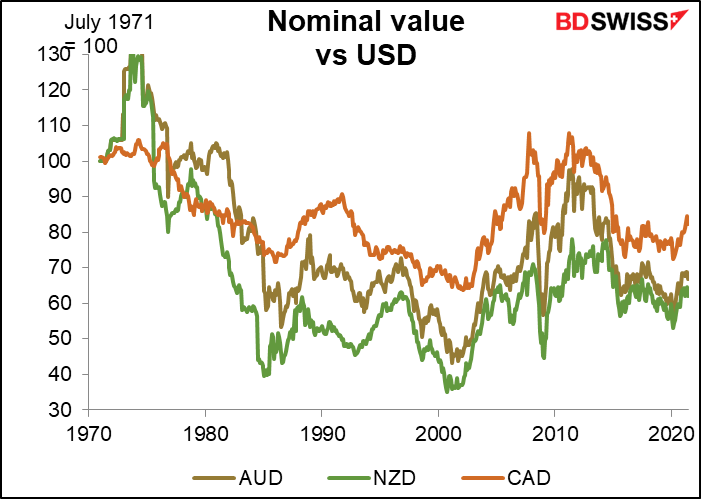

How have the major currencies fared under this system? Some have done better than others.

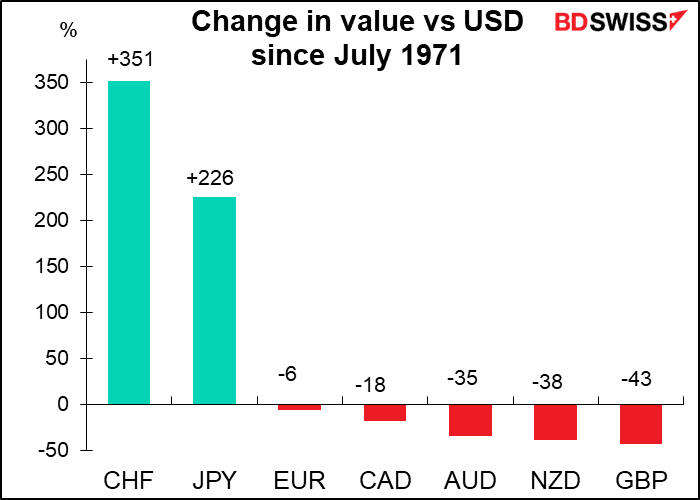

If we look at just the nominal value of the currency vs the dollar, then the Swiss franc and Japanese yen are the clear winners. The others have largely depreciated, with the pound the biggest loser. (The euro is artificially calculated before its launch.)

These changes represent only the price return. They don’t include interest payments and so don’t represent the total return one would’ve gotten from holding these currencies over this time period. I don’t have the data to make that calculation, nor is it available on Bloomberg. (I did run that calculation from August 1980 and came up with a totally different order: NZD was #1 and JPY, which has paid around zero interest since 1995, was last.)

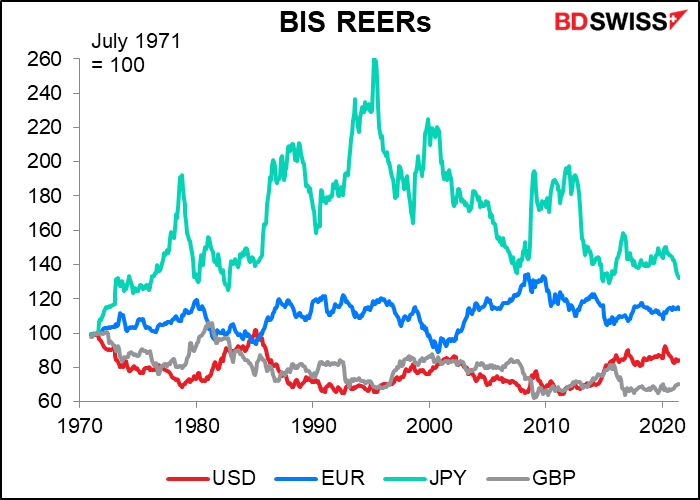

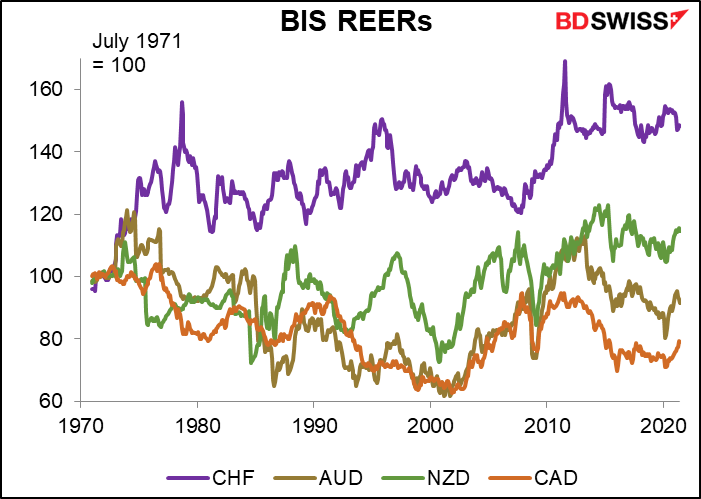

In any event, the changes in relative price of the various currencies are to some degree optical illusions because the inflation rates of the countries are different and the nominal value of a currency should naturally adjust to take that into account. For example: Let’s assume that USD 1 = JPY 100 and that a widget that costs $1 in the US costs JPY 100 in Japan. Let’s then assume that the US has 5% inflation and Japan has 2% deflation. At the end of one year the widget will cost $1.05 in the US and JPY 98 in Japan. For the real value of the USD/JPY exchange rate to stay the same, the nominal rate will have to move to 98/105= 93.33, or $1 = 93.33 yen. Did the yen appreciate or stay the same? The nominal value appreciated but the real value stayed the same.

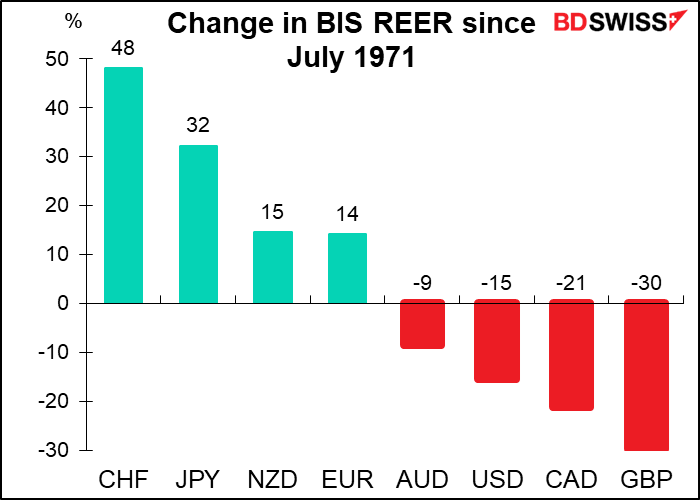

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) calculates an index of the real value of each major currency against the currencies of its major trading partners (called the real effective exchange rate, or REER). On this basis, the NZD has done much better and the USD worse than the nominal changes would imply. The low-inflation CHF and JPY are still the overwhelming winners, although by no means as much, and the poor beleaguered pound the loser, albeit by less.

Not to show my age, but I was a high school exchange student in Japan when Nixon tore the global monetary system apart. The area where I was living, Fukui Prefecture, was hard-hit by the sudden appreciation of the yen. I lived near Sabae, the-then world’s capital for making eyeglass frames. Even today they make some 25% of the world’s eyeglass frames there, apparently. I had to make a speech to the local Rotary Club shortly after this event. Torn between loyalty to my President and the desire to placate my audience, needless to say I blasted Nixon’s perfidy as best I could in my poor Japanese. Given that I was near draft age and not a big fan of Nixon’s Vietnam policy, this bit of disloyalty did not cause me many sleepless nights.

I owe my career as a forex strategist to this event, so I’m quite grateful that Nixon did it.

Next week: FOMC minutes, RBNZ, US retail sales

There’s a good deal of data coming out next week.

The main point of interest might not actually be so interesting, but every month – well, eight months out of the year – we are riveted by the release of the minutes of the last meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the rate-setting body of the US Federal Reserve. The meeting that took place on July 26th was one where they definitely were discussing when they should begin tapering down their $120bn-a-month purchases of US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. Everyone will be pouring over the minutes with a level of scrutiny previously reserved for the lineup of Kremlin officials watching the annual Moscow Victory Day Parade in an effort to glean some insight into what would constitute “substantial further progress,” which is the purposely vague criterion they’ve set for starting the tapering process.

The problem is, since the meeting took place we’ve heard from a wide number of Committee members on this issue, so how will the minutes add to our understanding of the debate? They’ve continued to carry on the debate in public over the last two weeks. But then again, the markets don’t need “new news” to move. They will often move on “old news,” that is, confirmation of an existing impression.

The minutes never tell us how many people hold a particular opinion, but they do have set counting words: “all,” “all but one,” “almost all,” “nearly all,” “most,” “many,” “several,” “a number,” “some,” “few,” “a couple,” “one.” Since there are 18 members of the FOMC, “most” means 9 or more. “Several” usually means between five and seven. “A number” and “some” generally mean four or five – they use these interchangeably just to vary the style. “A few” is three or four, usually three, while “a couple” usually means two but can mean three if the view is implicit or not strongly held.

My guess is that the minutes will include “a few” or “a number” of participants will be revealed to have pressed for tapering to occur sooner rather than later, but “a number” or “many” will have argued that the labor market is still weak and so they want more time to see more data. If however they use the same adjective to describe both groups, then we have an interesting situation.

We also have to watch between “members,” who are those with a vote, and “participants,” who include the non-voting regional Fed presidents as well. Traditionally the FOMC vote is by consensus, meaning that this distinction usually isn’t that important, but when push comes to shove it has indeed happened that a vote is determined by one person (10 times in the 814 meetings from 1936 to 2020), so the distinction is worth bearing in mind.

Separately, Fed Chair Powell will host a town hall meeting with educators and students on Tuesday. He will take questions from them. Will he say anything new? Probably not. Might it move the markets anyway? Possibly. You can watch the event live if you want, either on their website or on YouTube.

RBNZ: the first G10 rate hike

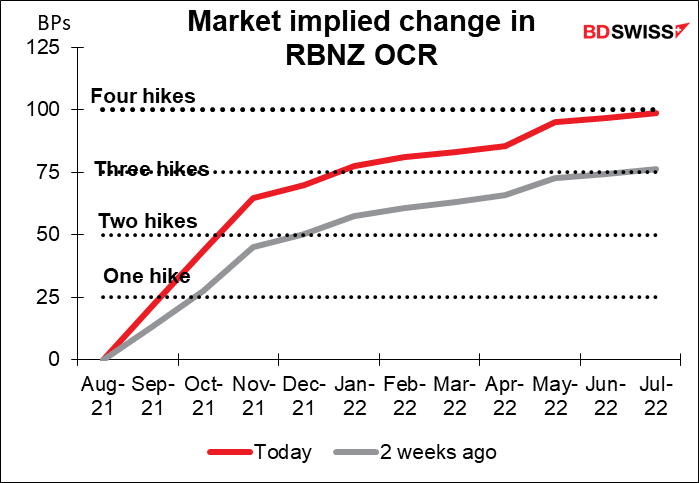

The market is expecting the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) to raise its Official Cash Rate (OCR) by 25 bps to 0.5% next week. This would be the first hike by the RBNZ in seven years and the first of any G10 central bank in this cycle. In fact, rate hikes aren’t all that uncommon nowadays – some 23 central banks have raised rates so far this year, with yesterday’s 25 bps hike by Bank of Mexico being the latest. Nonetheless this would be a dramatic turnaround for the RBNZ. As recently as May they were saying that it would take “considerable time and patience” to meet their criteria for tightening policy.

New Zealand faces a different set of conditions than other countries. Most notably, its virus crisis is totally different thanks to its modern-day sakoku policy – the “policy of controlled and very limited external contact” that Japan instituted during the Tokugawa era. By closing off their island kingdom, they’ve managed to keep new virus cases down to the single digits per day – I can’t even produce a decent graph of them.

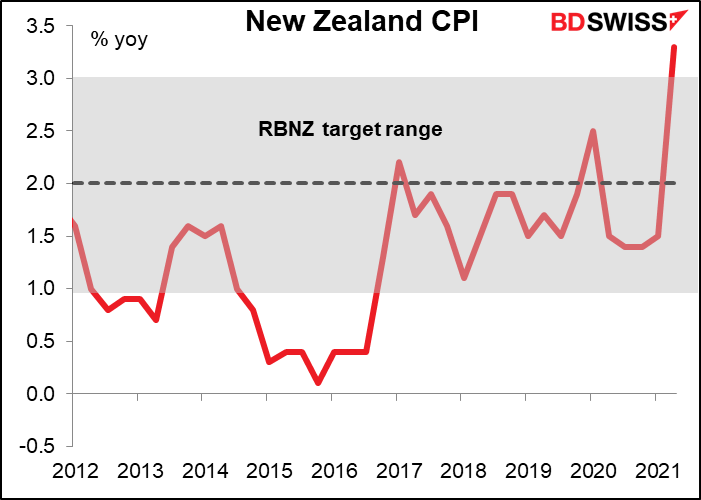

As for their tightening critera, inflation has pushed abover the RBNZ’s target range, satisfying their criterion that “consumer price inflation will be sustained near the 2 percent per annum target midpoint.”

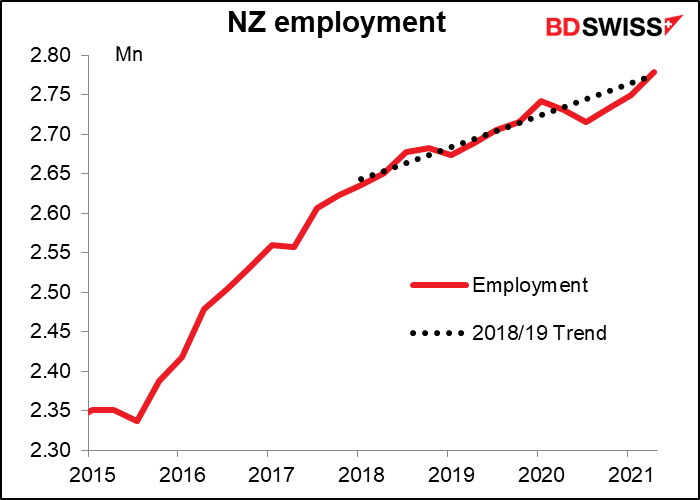

And employment has already recovered back to the pre-pandemic trend, which satisfies their other condition that “employment is at its maximum sustainable level.”

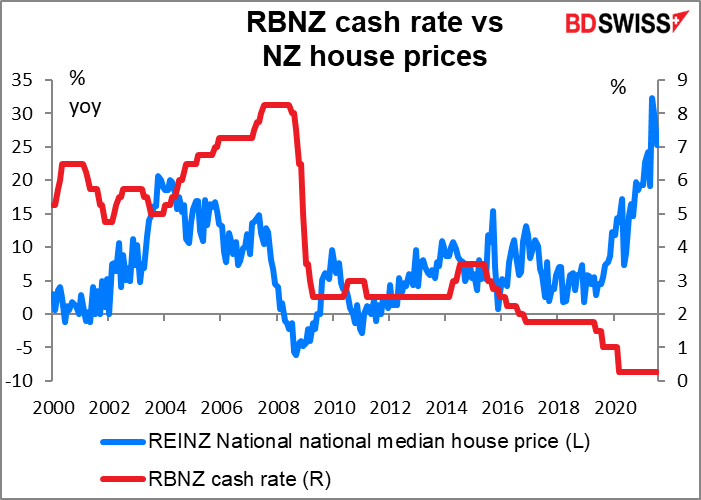

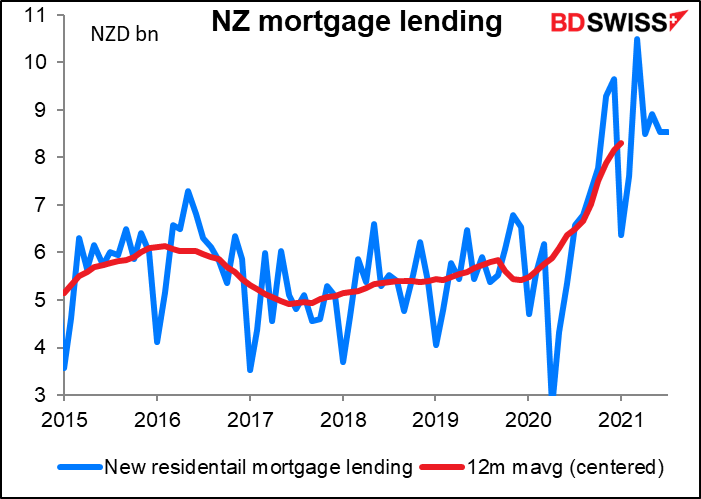

Meanwhile, they’re also seeing the same sort of house price boom that other countries have been seeing.

There’s some speculation that they could go 50 bps this time, but I think that would be quite aggressive and needlessly boost the exchange rate when the global recovery is still somewhat fragile.

Given that the rate hike is already discounted, the market reaction will depend on how aggressive they sound in their commentary and what kind of forward guidance they give. I suspect that they might want to take a “wait and see” attitude after this one hike. That could be negative for NZD.

US indicators: retail sales, Empire & Philly Fed indices

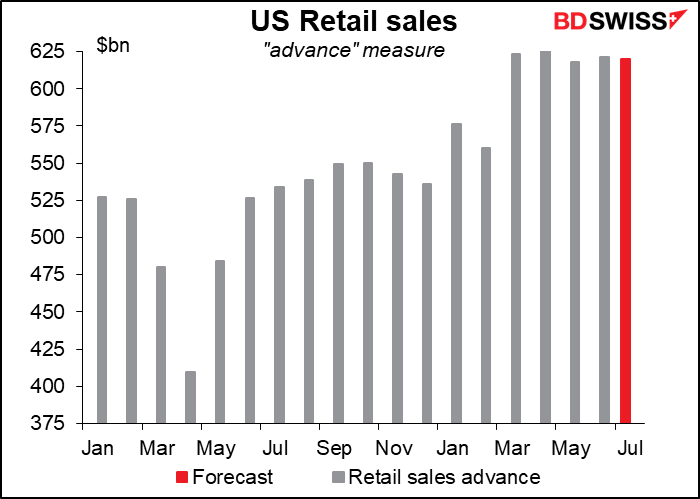

The US retail sales on Thursday will be the big indicator of the week. The market is looking for a small decline in sales.

Even so, on that basis sales would be some 18% higher than before the pandemic. That doesn’t seem sustainable.

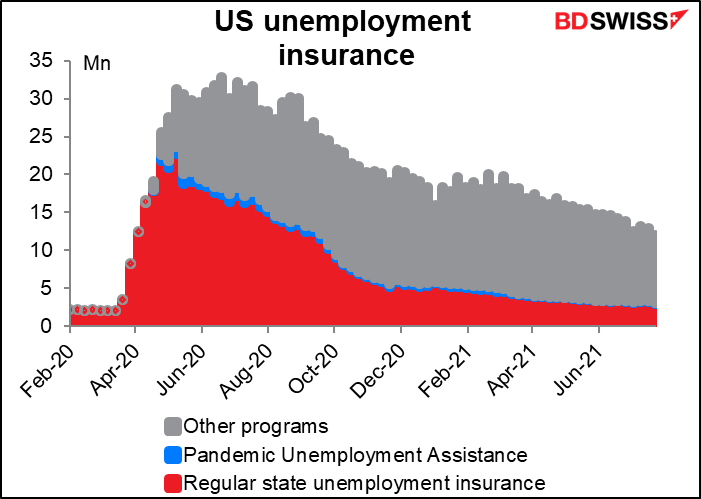

One of the key questions economists face going forward is, what will happen to the US economy once the extraordinary unemployment benefits from the federal government expire in September? We’ve gotten an inkling of that already as many states have been ending them early. While the number of people claiming regular state unemployment insurance has come down considerably, the total number on all programs is still stunningly high: 12.1mn, vs an average of around 2.2mn in January 2020, before the pandemic hit. What will support the US economy once these people have exhausted their benefits? Will the job market improve, or will the Biden Administration’s infrastructure rebuilding plans provide enough jobs to make up for the lost benefits?

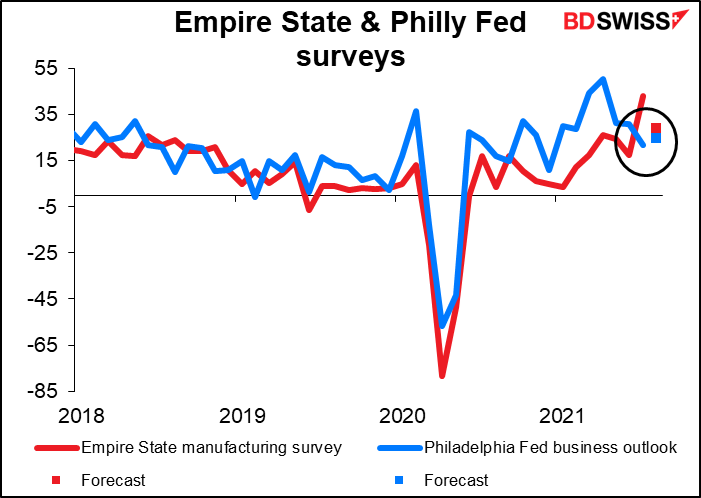

Other important US indicators coming out will be the Empire State manufacturing index (Tue) and the Philadelphia Fed business sentiment index (Thu). For some reason the Empire State index is expected to be down 14 points while the Philly Fed index is expected to be up 3.1 points – the idea being I suppose that they should converge more.

We will be getting inflation data from the UK and Canada on Wednesday and Japan on Friday.

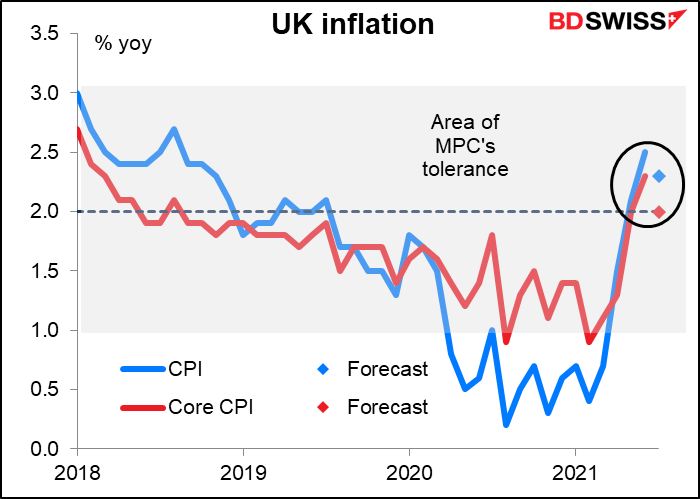

Britain’s inflation rate is expected to fall, with the core rate coming back to exactly the 2% line. This might surprise the the Bank of England, which said after its August 5th meeting that “CPI inflation is projected to rise temporarily in the near term, to 4% in 2021 Q4, owing largely to developments in energy and other goods prices, before falling back to close to the 2% target.” That could be a GBP-negative development.

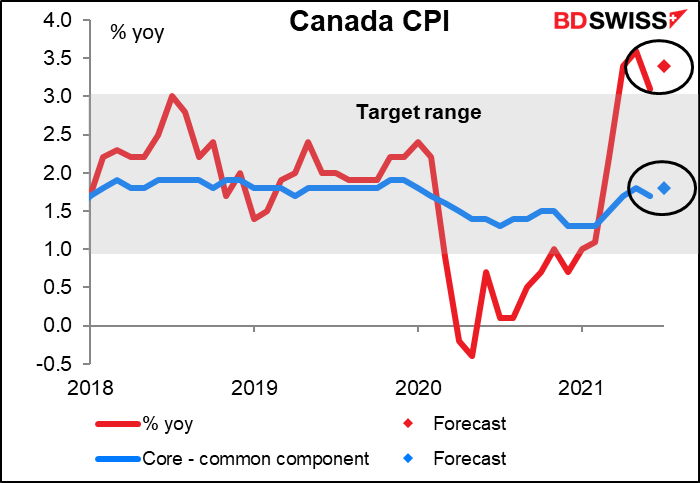

Canada’s CPI is expected to accelerate somewhat, but the core measure, which is what they say they make their decision based on, is expected to remain below the middle of their 1%-3% target range. The rise in the headline figure could prove positive for CAD nonetheless.

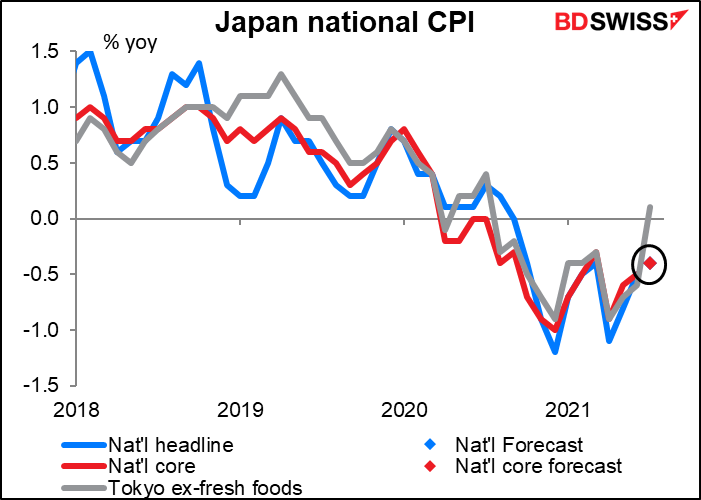

Japan is expected to remain in deflation, but nobody cares because the Bank of Japan isn’t going to do anything about it anyway. In truth we should note that this might be what’s called “good” deflation in that its main cause is not a lack of demand but rather the government forcing mobile phone operators to cut their rates, which will save me some money as I have a talkative daughter in university there.

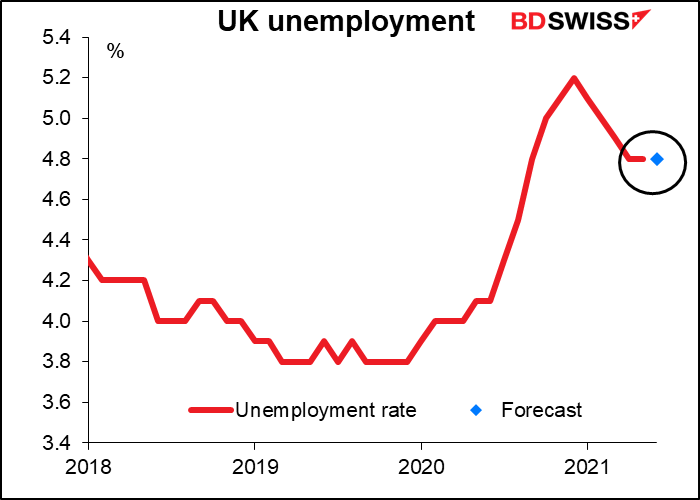

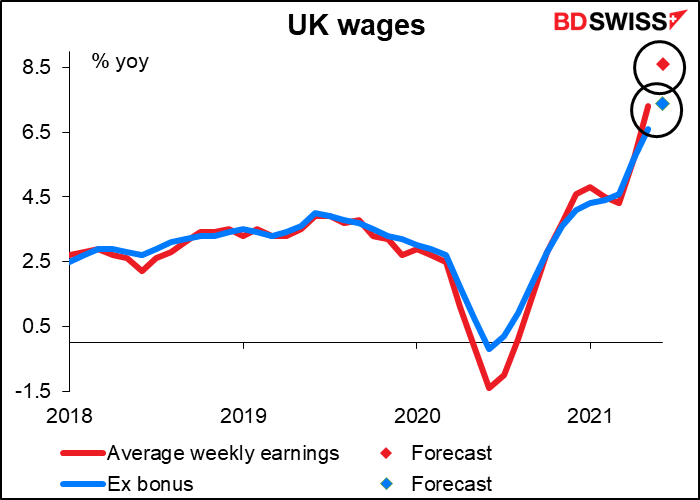

Britain will also announce its employment data on Tuesday. It doesn’t look like this will clear up the contradictions that the BoE pointed out in the minutes of its latest meeting. “The increases in unemployment, inactivity and the number of jobs furloughed since the onset of the pandemic suggested a material amount of labour market slack,” they said. “Other indicators pointed to the labour market having been tighter, however.” They then launched into a list of indications of why the labor market might be considered tight. They also noted that the underlying rate of growth in wages was back to where it was before the pandemic.

However, according to the market’s forecasts, the unemployment rate stalled at 4.8% while wage growth rose. So is the labor market stalling or improving? We still don’t have a clear signal.

The Bank of England doesn’t have an explicit “dual mandate,” but it is required “to support the economic policy” of the government, “including its objectives for growth and employment.” A recovery in employment and wage growth coinciding with above-target inflation would make a better case for tightening policy.

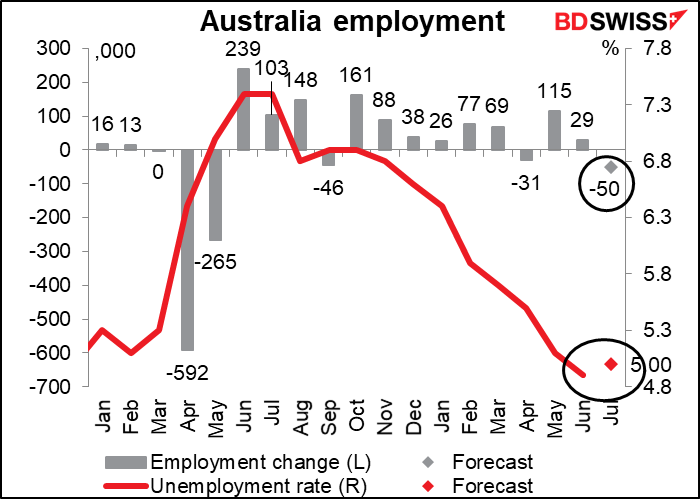

Australia will also release its employment data on Thursday. The number of people working is expected to fall by 50k while the unemployment rate is forecast to rise one tick to 5.0%. This is not surprising, given the deep lockdown that the country has been experiencing. I’d say the risk is that employment falls by even more and the figure proves negative for AUD. At their last meeting, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) confounded the experts (read: me) and kept policy steady instead of loosening in some way to take into account the worsening virus situation. A rise in the unemployment rate might convince them to do otherwise, or at least get the market speculating on whether they might do otherwise. AUD–