We should’ve known something was up from the speeches made on Nov. 22nd when President Biden reappointed Fed Chair Powell and appointed Gov. Brainard as Vice Chair. “We’re in a position to attack inflation from a position of strength, not weakness,” Biden said then. Inflation, not unemployment. Both the appointees echoed that idea: “We know that high inflation takes a toll on families . . . We will use our tools both to support the economy and a strong labor market and to prevent higher inflation from becoming entrenched,” Powell said, while Brainard added that she was committed to “getting inflation down at a time when people are focused on their jobs and how far their pay checks will go.”

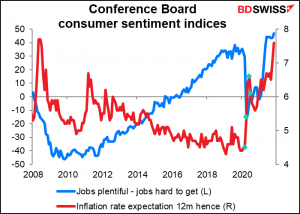

The Fed is independent, but Board members aren’t stupid. They don’t want to be seen as partisan hacks like the Supreme Court is nowadays, but at the same time they must be aware of what the Administration wants and also what the mood in the country is. And right now, it’s inflation that’s bothering people, not unemployment. The Conference Board survey of inflation a year from now is at 7.6%, almost equal to the highest on record (7.7%, set in 2008 – data back to 1987), while the “jobs plentiful” index minus the “jobs hard to get” index, a measure of people’s confidence in the job market, is at a record high.

Powell doubled down on these sentiments in his testimony to Congress this past week, when he said he believed that high inflation would persist until the middle of next year and so the Fed is « likely » to discuss speeding up the tapering of its asset-buying program. While he still thinks it’s likely that inflation will come down « meaningfully » in the second half of next year, « the risks of higher inflation have moved up,” he said. « We have to use our policy to address the range of plausible outcomes, not just the most likely one.”

(Parenthetically, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) agreed with this assessment. In its twice-yearly economic update, released Wednesday, it significantly raised expectations for G20 inflation in 2022 to 4.4% from 3.9% in September, with the largest increases in the US and UK.)

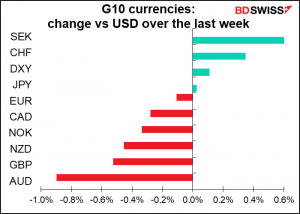

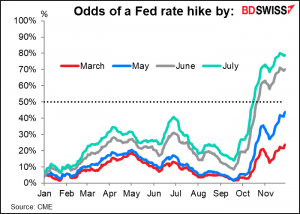

The market had been expecting the Fed to start hiking rates in June, when it’s scheduled to end its bond purchases. As a result of Powell’s comments, the odds that they end their bond purchases earlier – and therefore can start hiking earlier – increased. An earlier-than-expected rate hike by the Fed would be positive for the dollar.

The elephant in the room though is the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus. OECD Chief Economist Laurence Boone said she fears the Omicron variant could add to « the already high level of uncertainty and that could be a threat to the recovery, delaying a return to normality or something even worse. » She added though that higher prices warranted higher interest rates and a slightly tighter monetary policy.

I have to say though that I see a lot of evidence that inflation is peaking, or at least the causes of inflation are peaking.

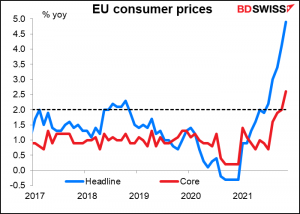

For example, EU-wide inflation hit 4.9% yoy in November, which European Central Bank (ECB) Governing Board member Isabel Schnabel said the ECB believes that this is the peak for inflation in the Eurozone.

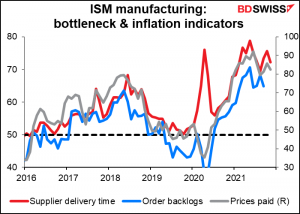

This week’s Institute of Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing sector purchasing managers’ index (PMI) shows that supplier delivery times and order backlogs were coming down, indicating that bottlenecks may be easing. The prices paid index also declined.

Shipping costs have started to come down, albeit from incredibly elevated levels. This indicates that one of the major bottlenecks forcing up prices of many goods is starting to unwind.

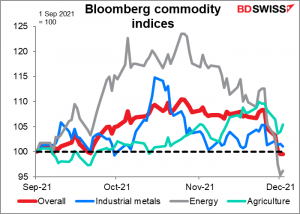

Commodity prices have started to come down, including economically sensitive industrial metals, as well as the wildly expensive natural gas (not specifically shown but included in the “energy” sub-index).

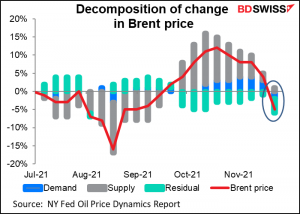

And of course oil prices have plunged, although the surprise decision by OPEC+ to raise output by 400k barrels a day as planned but keep open the option to revisit the decision at any time managed to put a floor under prices. The statement following the meeting said the group agreed “that the meeting shall remain in session pending further developments of the pandemic and continue to monitor the market closely and make immediate adjustments if required.”

I have to admit, this was a brilliant way to finesse the current situation in the oil market now, where it’s largely anxiety pushing prices down not supply or demand. The New York Fed’s Oil Price Dynamics Report breaks down the causes of changes in the oil price into demand, supply, and “residual” factors. Recently it’s been “residual” that’s been responsible for the drop in the oil price. This residual is no doubt fear of the Omicron variant and its effect on mobility. Assuming no change in supply or demand then, the elimination of this fear might well bring oil prices back up.

Next week: US CPI, JOLTS report, UK short-term indicator day, RBA and Bank of Canada meetings

Next week being the second week of the month, as usual there aren’t that many major indicators on the schedule.

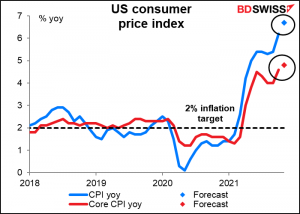

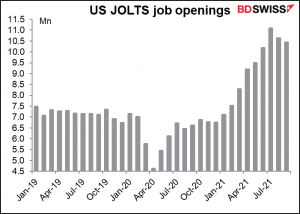

The big ones will be the last two US important data points that the Fed has with regards to its “dual mandate” before its Dec. 15th meeting, namely the November consumer price index (CPI) and the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) program. Maybe we should refer to these as 1 ½ important data points, because the JOLTS survey is second tier.

In her interview last week with Yahoo! Finance, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said she “certainly see(s) a case to be made for speeding up” the tapering process. She continued,

We have two important data points that are going to come in before the next meeting, and will really inform my take, our deliberations, and certainly my thoughts. Those are another report on the labor market — another jobs report — and also another report for the CPI. And if things continue to do what they’ve been doing, then I would completely support an accelerated pace of tapering.

We’ll get that jobs report – the November employment report – later today. It’s expected to “continue to do what it’s been doing,” in fact the increase in nonfarm payrolls is expected to be nearly the same as in the previous month (548k vs 531k last month).

I was surprised that she mentioned the CPI report – supposedly the Fed uses the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator for its inflation gauge, not the CPI. That’s what the Fed expresses its forecasts n terms of.

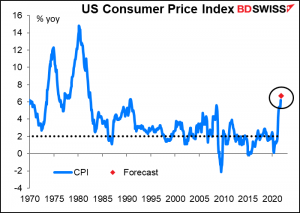

In any case, will inflation also “continue to do what it’s been doing”? In spades! The market was shocked last month when the headline CPI jumped from 5.4% yoy to 6.2%. This month it’s expected to leap further to 6.7%.

That would be the highest rate of inflation since the high-inflation days of the early 1980s, when the fed funds rate got up to as high as 22.4% (July 1981). What would former Fed Chair Paul Volcker, head of the Fed back then, think? He must be turning over in his 6’7” (2.01 meters) grave.

Given the concerns that various Committee members have expressed about inflation, I expect that a number like this would be enough to push them over the finish line to vote to accelerate the tapering.

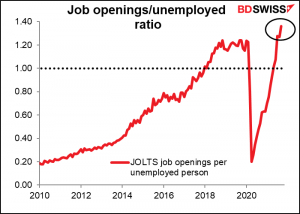

The JOLTS report should only confirm that view. This report shows how many job openings there are. Openings hit a record high in July and have come down somewhat since then, but not as fast as the number of unemployed persons has declined. (No forecasts available at the time of writing.)

As a result, the ratio of jobs to unemployed persons – similar to what they call in Japan the “job-offers-to-applicants ratio” –hit a record 1.36 last month and is likely to go even higher this month. I point this out because many officials use this ratio as a measure of how tight the job market is. What this ratio suggests is that there is either a huge gap between the skills on offer and the jobs available, or where the unemployed are vs where the jobs are, or that many people have changed their minds about working. Probably the latter. This kind of change in the desire to work changes how we the Fed will view metrics like the participation rate when it tries to measure whether the economy is near “full employment.”

In the UK, Friday will be “short-term indicator day,” when the Office of National Statistics spews out the monthly GDP, industrial and manufacturing production, and trade statistics.

GDP growth is expected to slow, presenting a conundrum for the Bank of England as inflation skyrockets. Can they tighten policy while the economy is headed down the tubes, thereby adding to everyone’s misery? Slowing growth could be negative for the pound.

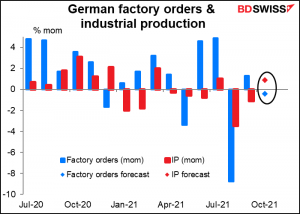

Finally, in the EU we have German factory orders on Monday and industrial production on Tuesday. Factory orders are expected to be lower, but industrial production is expected to be up for the first time in three months. Orders look weak to me; a plunge in August, a small recovery in September, and now another decline. It doesn’t look good. I’d say this could be negative for EUR.

Central bank meetings: RBA and Bank of Canada

Two of the commodity currency central banks, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and Bank of Canada (BoC) meet next week. Neither is likely to change their rates or adjust policy in any form. They will mostly be watched for any hints of when “lift-off” might come and at what pace they’re likely to tighten policy.

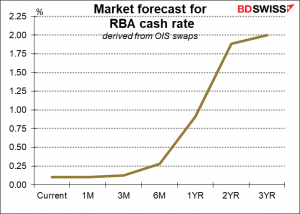

The RBA’s final board meeting of the year is likely to prove uneventful. They said last month that they would “continue to purchase government securities at the rate of $4 billion a week until at least mid-February 2022,” which is the next meeting after this one. With no change in asset purchases likely and of course no change in rates, the focus will be on any change in their forward guidance, which currently hints at the possibility of a rate hike “at the end of 2023.”

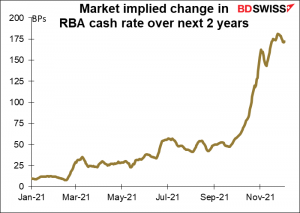

The market begs to differ, and not by a small amount; it sees 175 bps of tightening by end-2023.

The market expects the first rate hike in about six months, not two years.

In that respect, the main focus will be on what if any changes they make in their forward guidance and what hints they give about the likely decision on bond purchases in February. Given the increase in global inflation and the Fed’s capitulation with regards to “transitory,” I’d expect them to take a more hawkish view of things. Q3 GDP was better than expected, they may have an improved view of Q4. Accordingly, I’d expect them to build more optionality into their forward guidance, allowing for the possibility of an end to the bond purchases in February and an earlier hike in rates. That could prove positive for AUD.

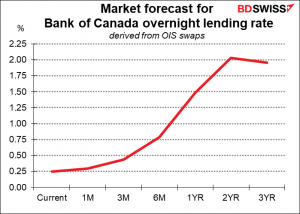

Similar for the Bank of Canada. At its last meeting, the BoC ended its quantitative easing program and moved up its expected date for “lift-off” to “the middle quarters of 2022” from “the second half of 2022.” The market already foresees a rate hike by March; I doubt if anything the BoC could say would accelerate that timetable, given that there’s only one meeting between next week’s and the March meeting (Jan. 26th).

The market is already looking for a fairly steep tightening cycle (dotted line) by historical standards. I can’t see this being revised higher any time soon, given the uncertainties in the global economy (read: virus). Accordingly, I expect little impact on CAD from this week’s meeting.