It shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did. In fact it amazed me.

Thursday’s US consumer price index was expected to be up 4.7% yoy – instead was up 5.0%. The core index rose 3.8% yoy, surpassing expectations of a 3.5%yoy rise.

And yet…bond yields fell (prices rose) and the stock market rallied!

Now, what I should’ve done before the announcement is gone back and re-read what I wrote following the higher-than-expected April CPI:

The surprise of the week just ending was the dog that didn’t bark – the muted reaction (no reaction, in fact) to the higher-than-expected US consumer price index (CPI). Everyone was primed for a leap higher in bond yields as the CPI was expected to show inflation leaping over the Fed’s target. In the event it leaped even higher, and yet inflation expectations fell.

If inflation expectations can fall in the face of a 2.6% yoy reading of the CPI, what could change the market’s view on inflation? I suspect it would be not so much a certain level as a “string” of high inflation figures over the next few months…and gradually people may change their minds…

So this month was quite a lot like last month, only more so, because we are getting the “string” of higher inflation figures that I talked about and yet the response is the same.

The answer may be that the market is more and more believing the Fed’s argument that the higher inflation is “temporary” and “transitory,” caused largely by distortions due to the pandemic. It’s like the mouse passing through the snake – it leaves a big lump as it progresses, but eventually it’s all digested.

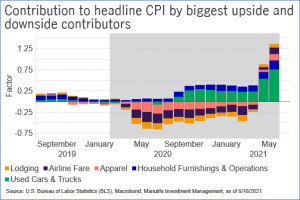

Note that those areas that were forcing inflation down during the pandemic (such as lodging, airfares, apparel) are now unwinding those moves. On the other hand those areas that were pushing inflation up during the pandemic (used cars, household goods) have yet to reverse their trend, but eventually they will. The incredible surge in used car prices for example, which accounted for about one-third of the overall rise in the CPI in both April and May, has a specific cause — car rental companies rebuilding their fleets. Once that’s over, it’s over.

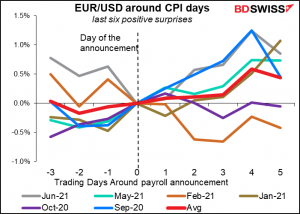

In any case, the impact of the US CPI on the dollar has been counter-intuitive for some time. Following positive surprises – i.e. when the CPI comes in higher than expected – the dollar has tended to depreciate (EUR/USD moved higher).

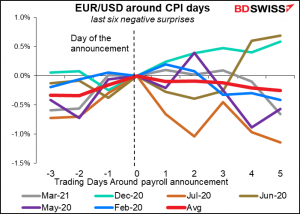

But when the CPI missed estimates and came in lower than expected, EUR/USD tended to move lower, i.e. the dollar strengthened – although for the first few days after the announcement it was 50-50.

This isn’t what I expected to find when I made these graphs. On the contrary, a higher-than-expected figure should tend to make people revise up their estimates of when the Fed might begin normalizing rates. That should cause the dollar to appreciate. Furthermore, earlier expectations of Fed tightening would tend to provoke a “risk-off” environment, sending stocks down. The dollar usually appreciates in a risk-off environment.

The only thing I can think of is that perhaps the new “average inflation targeting” (AIT) regime has caused markets to go back to pricing in inflation the way they used to before inflation targeting became the norm. It used to be that higher inflation was negative for a currency because inflation is by definition the loss of purchasing power. Currencies would fall when the CPI rose. That all changed starting in the early 1990s, when central banks around the world began targeting inflation and the markets took into account the new central bank reaction function. Whereas previously higher inflation meant a loss of purchasing power, now it meant higher interest rates, which made a currency more attractive to hold.

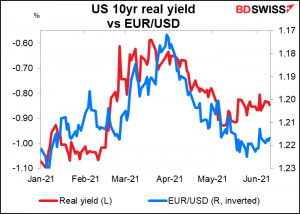

That’s all changed under AIT. For the time being, higher inflation won’t necessarily trigger higher interest rates in the US (or elsewhere, for that matter, because most central banks are more worried about growth than inflation. See the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and its “least regrets” policy). So as inflation rises but interest rates don’t, real interest rates decline. That could be one reason why a higher-than-expected CPI caused the dollar to weaken: expectations of lower real interest rates.

In fact we have seen EUR/USD tracking real US interest rates recently, so this seems to be the most logical answer.

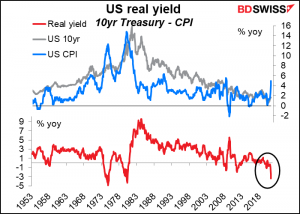

But it begs the question: why aren’t nominal rates moving up? Why aren’t nominal rates moving up in response to the higher inflation? Because real rates are now the lowest they’ve been since at least 1953, with the exception of two periods of unusually high inflation in 1974/75 and 1980. Presumably the market expects that the current unusually high inflation is going to be as transitory as those periods were.

The big question of course is, what does the Fed think about all of this? We should get some answers to that question next week, when the Fed’s rate-setting body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), meets on Tuesday and Wednesday. This meeting is particularly important as it will include a new version of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), including the FOMC members’ forecasts for growth, inflation, and the all-knowing, all-powerful dot plot with their forecasts for where the fed funds rate will be at the end of every year.

There are a few indications of how the Committee’s thinking might have changed that we can deduce from listing to what Fed speakers have had to say recently. For example, Fed Gov. Lael Brainard, who’s on the dovish side of the group, showed a more even-handed view in a recent speech to the Economic Club of New York.

Meanwhile, we’ve heard more calls to begin “thinking about thinking about” tapering down their bond purchases. At the April meeting, “a number of participants suggested that if the economy continued to make rapid progress toward the committee’s goals, it might be appropriate at some point in upcoming meetings to begin discussing a plan for adjusting the pace of asset purchases.” Since then, Philadelphia Fed President Harker (NV) and Dallas Fed President Kaplan (NV) have been quite vocal in their call to start discussing the issue “sooner rather than later. And even Vice Chair Clarida said “it may well be” that “in upcoming meetings, we’ll be at the point where we can begin to discuss scaling back the pace of asset purchases.”

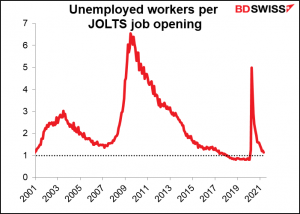

Some FOMC members have also expressed the view that there’s a “tight” labor market, focusing for example on the low number of unemployed persons relative to the number of jobs available.

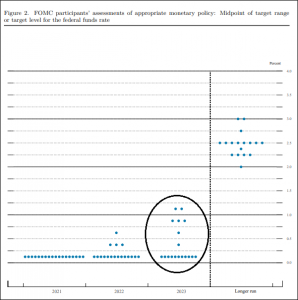

The focus will as usual be on the dot plot, which is how they concretely express their view of monetary policy. Last time, 11 out of the 18 people making forecasts said they thought rates would be unchanged until the end of 2023. This compares with 12 out of 17 at the previous meeting. At the other extreme there were two people at 1.125% in March, vs only one in December. So while the median dot remained unchanged, it’s clear that opinions were diverging. How much will they diverge this time? And in particular, will the median dot move up to 0.375%? Enquiring minds want to know!

I would expect to see:

- A more optimistic tone in the statement, with the first paragraph reflecting the improved economic outlook;

- Higher forecasts for both growth and inflation; and

- A few more people expecting a rise in rates by end-2023, but not enough to pull the median dot up (yet).

What we saw back in April was that improved economic forecasts combined with no change in interest rate outlooks implied lower real yields and was therefore considered negative for the dollar.

SNB & BoJ: not much of interest

The Fed isn’t the only major central bank meeting during the week. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) meets on Thursday and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) on Friday. Neither of these holds anywhere near the same interest for the markets however.

In the case of the SNB, it appears to me that they just use Tipp-Ex to white out the date on their statement every quarter and change it to that day’s date. (Does anyone nowadays remember Tipp-Ex?) They haven’t changed policy since 2015 and are unlikely to do so until after the European Central Bank has normalized policy, whenever that might be.

The Bank of Japan is similarly committed to keeping policy steady during the remainder of the Anthropocene Epoch or until the Rapture occurs, whichever comes first. With core CPI remaining in deflation thanks to cuts in mobile phone charges and Japan’s vaccination program lagging far behind the rest of the developed world, there’s little chance of the Bank even “thinking about thinking about” normalizing policy any time soon. Nobody in their right mind looks for any significant change at this meeting or indeed any other meeting in the foreseeable future.

There are two small issues to deal with this time. One, the BoJ’s special program to support corporate financing is scheduled to expire at the end of September. They may decide to extend it for another six months, following the government’s decision to extend its application deadline for loans from government-affiliated financial institutions by that long. That leaves open the question of how they will end the program. When the BoJ stops the purchases, the balance – currently JPY 68.6tn – will fall to zero. The monetary base will shrink, which might cause further yen strength and deeper deflation. At some point they’ll probably have to announce some way for companies to roll over these loans once the program is over so that the amount outstanding doesn’t just fall off a cliff.

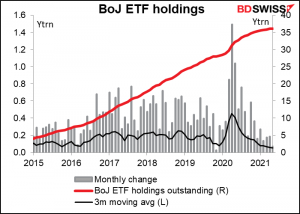

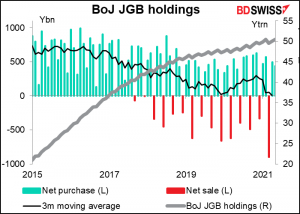

Secondly, there is some interest in the BoJ’s money market operations. In line with the operational changes it made at the March meeting, The BoJ hasn’t purchased any exchange-traded funds (EFTs) since April 21st and is unlikely to do so in the near future, given the stock market’s steady performance. The BoJ has also reduced its purchases of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs). The market will be interested to see if they make any comments on these two matters.

As for the indicators…

Tuesday is the big day for US indicators. Reports out on Tuesday include retail sales, Empire State manufacturing index, producer price index (PPI), and industrial production. Housing starts will be released on Wednesday and the Philly Fed index and weekly jobless claims on Thursday.

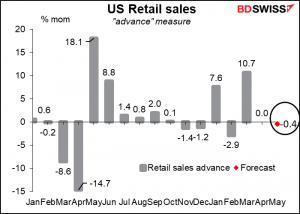

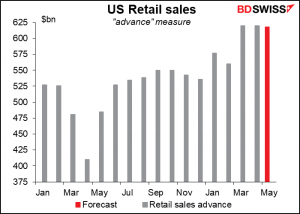

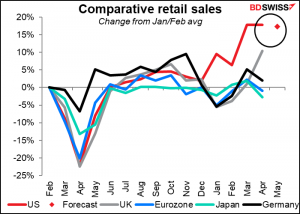

Of these, retail sales is no doubt the most important. Sales are expected to be down slightly, but I don’t think that really matters. Notice how they jumped in March when the supplementary payments hit peoples’ bank accounts. Sales were at the same high level in April too – no decline. So it’s no surprise that they would fall a bit in May. Indeed if anything the figure seems quite robust to me.

It’s easier to see as a level. If the forecast is correct, retail sales will be a stunning 17.3% higher than the pre-pandemic levels.

That goes a long way to explain why the US is roaring ahead of other countries in growth.

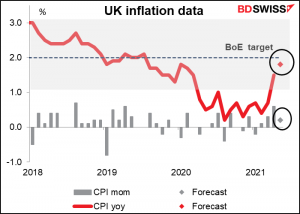

There are a number of major UK indicators out during the week: employment on Tuesday, CPI on Wednesday, and retail sales on Friday. Here it’s the CPI that’s the important point ahead of the June 24th Bank of England meeting. It’s expected to be up 1.8% yoy, almost the mid-point of the Bank’s 1%-3% target range. This should come as no surprise to the Monetary Policy Committee. At their meeting last month they said, “In the central projection, CPI inflation rises temporarily above the 2% target towards the end of 2021, owing mainly to developments in energy prices.” They said this was “transitory” and that they expected inflation to return “to around 2% in the medium term.” Still, hitting the target could tilt them toward a more hawkish stance, which could be positive for GBP.

Canada also announces its CPI on Wednesday; no forecast yet available.

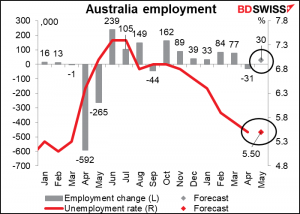

Australia employment data are due on Thursday. The expected small increase in jobs could be mildly positive for AUD.