The week started with great promise: a G7 Finance Ministers and central bank governors conference call to deal with the coronavirus menace. But what came out of that was, well, typical of the G7 nowadays – an agreement that everyone would do what they wanted to do. From what we’ve seen so far, what they want to do is to cut interest rates. During the coming week we’ll see how two more of the participants in that call – the ECB and the UK Treasury – interpret it.

The Statement of G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors didn’t say anything specific about what the group would do to combat the economic effects of the virus. The finance ministers simply reaffirmed their commitment “to use all appropriate policy tools” and said they are “ready to take actions, including fiscal measures where appropriate.” As for the central bankers, they will “continue to fulfill their mandates.” We can analyze these statements using the “Gittler Inversion Rule,” which postulates that a statement whose inverse is meaningless is also meaningless itself. In this case, would the participants have ever said the inverse: “we will use inappropriate policy tools” or “we will stop fulfilling our mandates”? Of course not.* Then the original statements were meaningless themselves, because they are obviously what they’re going to do anyway.

(*actually, Bank of Canada Gov. Poloz hinted that they would do exactly that — he said that the downside risks to the economy outweighed the concerns that the Bank of Canada has about lower interest rates possibly fueling higher household borrowing and increasing financial vulnerability.)

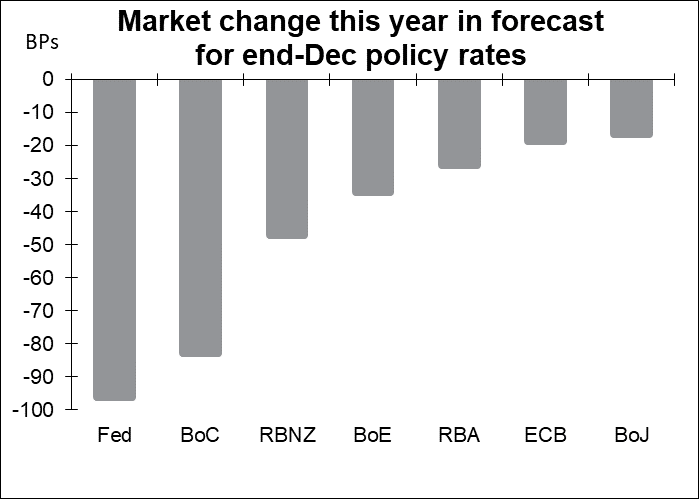

Meaningless though the statement was, it did precede action by the Fed, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and the Bank of Canada. At the same time, investors expect change from the others too. The following graph gives the change in the market’s expectations for end-2020 policy rates from the start of this year to now. The biggest change is of course in the US, where the market is now forecasting four more 25 bps rate cuts than it was forecasting at the beginning of the year (not hard to envision, seeing as we’ve already gotten two). Even the ECB, with its negative rates, and the Bank of Japan, with its 20-year-old ZIRP policy, QQE with YCC, BoJ buying ETFs, and a host of other acronyms are both expected to ease further.

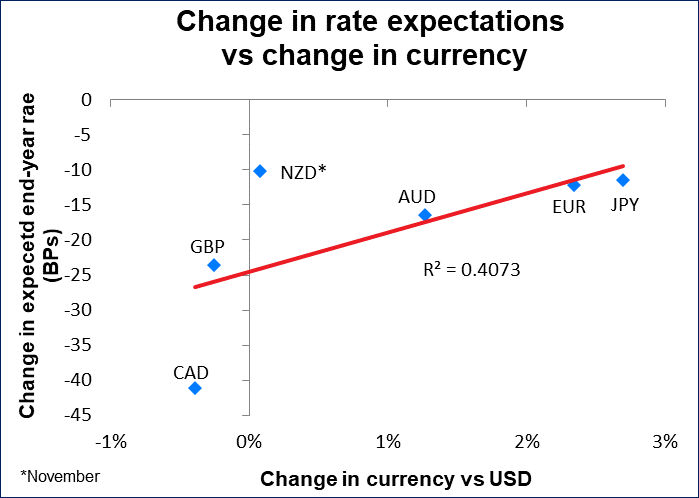

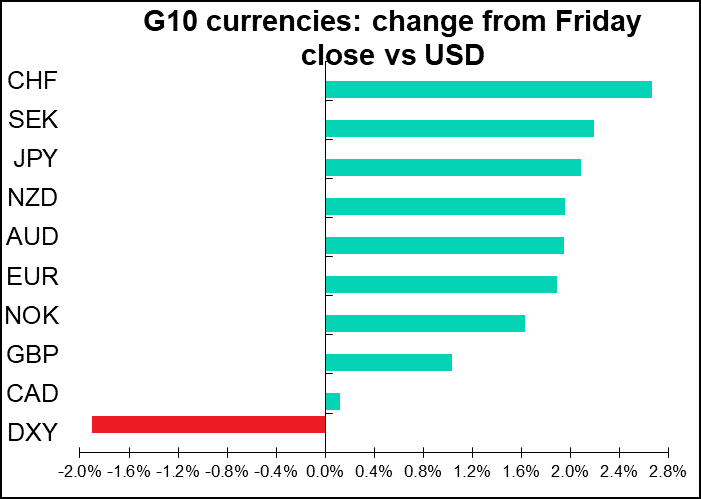

How did the FX market respond? The change did affect currency values – in general, those currencies that saw a bigger drop in their expected end-year rate also saw a bigger drop in their value vs USD.

But even more important was the absolute value of the expected year-end rate. That had a much higher correlation with the change in the currency’s value than did the change in expected end-year rate. The two currencies that have negative rates (EUR and JPY) appreciated vs USD, while those with the highest expected interest rates at the end of the year were the ones that fell the most. In that respect, it looks like we may be seeing a simple carry trade unwind, rather than a reevaluation of the prospects for central bank policy.

Meanwhile, the impact on markets has been extraordinary. Ten-year US Treasury bonds hit record low yields I gather (I don’t have my copy of A History of Interest Rates handy so I’ll have to take other people’s word for it) and the 30-year real US TIPS yield turned negative. On the other hand, the gold/silver ratio (96.26) is the highest it’s been since 27 February 1991 (99.72), as far as I can tell.

And while all this is going on – while US stocks are plunging and the financial world is fleeing to the safety of Treasury bonds – the Shanghai Shenzhen CSI 300 stock index is nearly at a two-year high, apparently on the assumption that the government’s fiscal & monetary stimulus will bring about economic nirvana. This while the China purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) plunge to unheard-of levels not even seen in the dark days of 2008/09.

This coming week: UK budget, ECB, US CPI

We’ll see how two more of the participants in that conference call think “the appropriate policy tools” are when UK Treasury announces its 2020 budget on Wednesday and the European Central Bank (ECB) meets on Thursday.

The UK Budget will be the first and best test of this new coordination between the fiscal and the monetary authorities. UK PM Boorish Johnson Thursday held a joint meeting with the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, and outgoing Bank of England Gov. Mark Carney. Johnson later said on TV that “We will make sure that we give UK businesses the support that it needs.”

There’s no point in speculating on exactly what measures the government might announce. I’ll just point out that even under the current fiscal mandate, the Chancellor can find room for an additional GBP 60bn in spending over the next four years and still run a current budget balance. He could also change the rules in ways that allow him to spend more money, such as shifting to a rolling average for the budget balance over several years, just like monetary policy aims for inflation at a certain level over the medium term and not necessarily every month. Or he could fiddle with the definition of “budget balance,” such as use a “structural” budget deficit to allow for such shocks or targeting the debt-to-GDP ratio. So I think we can look for both an expansionary fiscal policy and a more stimulative monetary policy.

Gov. Carney was also in an expansive mood. He said that the BoE was “coordinating with HM Treasury to ensure that any initiatives are complementary and that they will collectively have maximum impact.” He noted that the BoE’s “policy arsenal includes monetary policy instruments, special liquidity facilities, and macroprudential tools.” This echoed comments by incoming BoE Gov. Andrew Bailey, who Wednesday said that he will co-ordinate the Bank’s response with the government. Bailey takes over on 16 March and the next Bank of England policy announcement is due on 26 March, but it looks to me like they’re planning to make an announcement on the same day as the Budget to reinforce the message of support. The market is forecasting at least a 25 bps cut at the meeting and a 50-50 chance of a 50 bps cut. We should watch for that next week however, as Carney hinted.

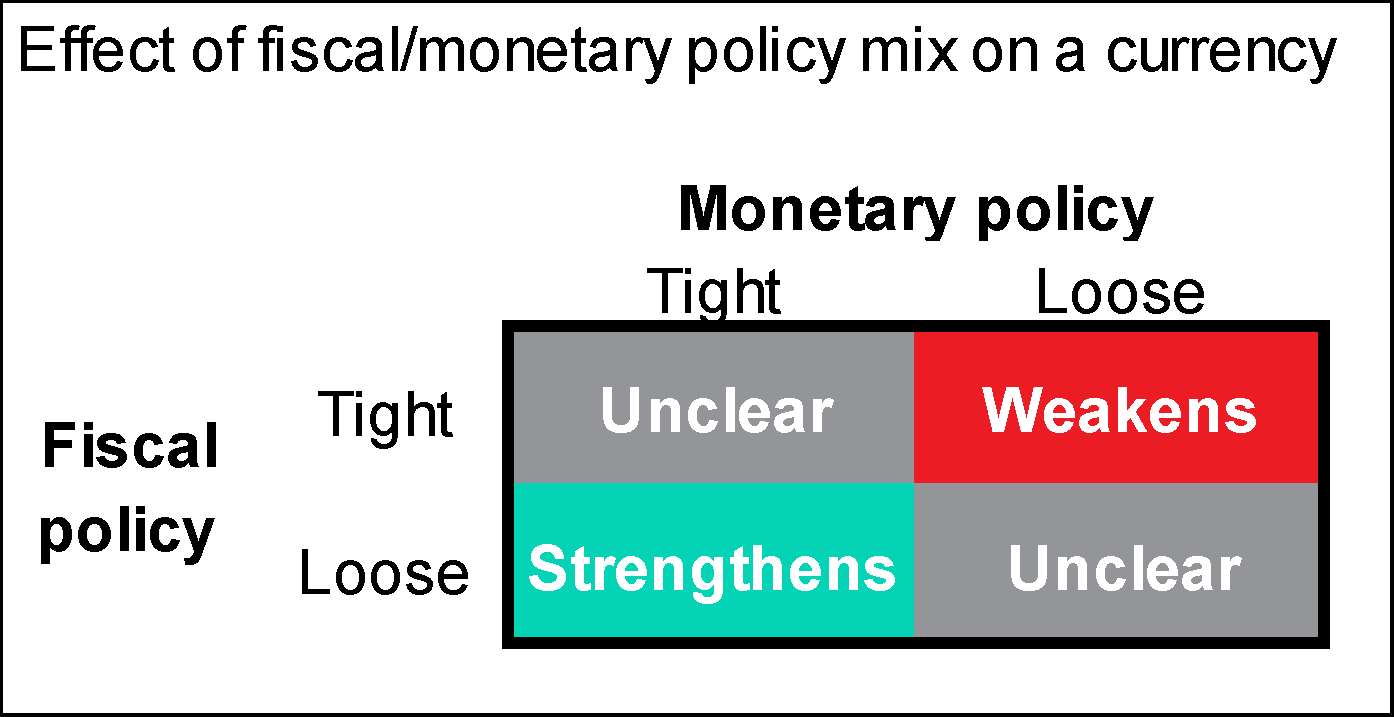

How might this policy mix affect the pound? It’s not immediately clear. A tight fiscal/loose monetary policy normally causes a currency to depreciate, while a loose fiscal/tight monetary policy causes a currency to appreciate, but when both are loose or tight, it’s not certain what will happen.

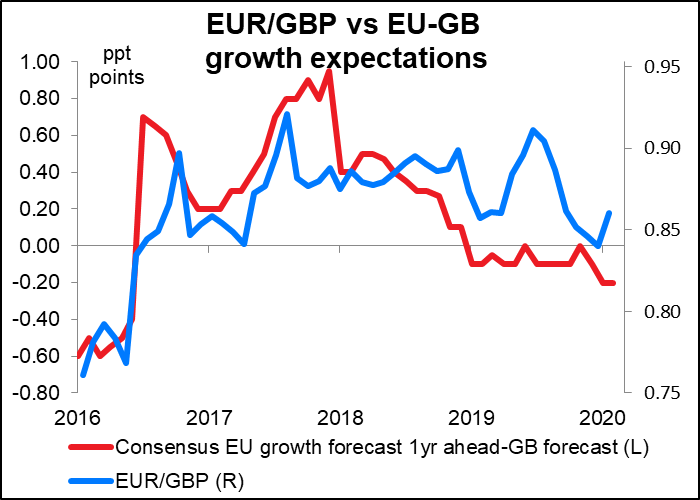

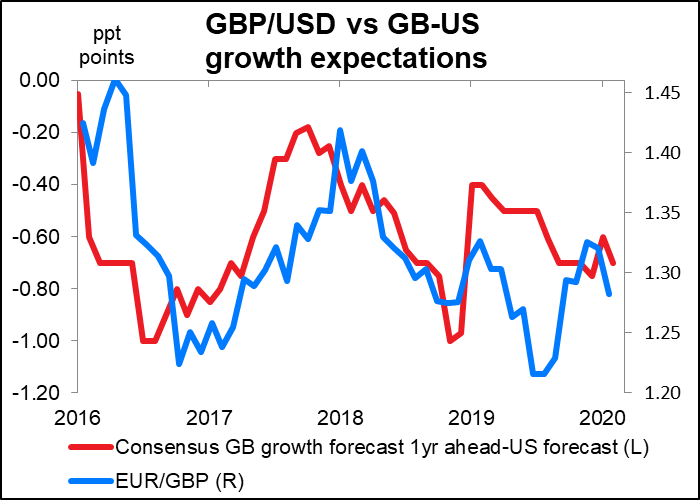

In this case, I think it’s likely to cause GBP to strengthen, because of the impact on growth. We can see that in general, both GBP/USD and EUR/GBP are sensitive to growth differentials. The fact that Britain has room to stimulate its economy with both fiscal and monetary policy certainly is an advantage over the Eurozone, where fiscal policy is impossible to coordinate and monetary policy is already at nearly full throttle.

The US has perhaps more room to ease on the monetary front than Britain does, but it’s hard to imagine a more stimulative fiscal policy than what the Trump regime has already enacted. We could therefore see GBP gaining vs EUR more than vs USD, although at the moment that’s not the case.

In any event, I suspect that during the rest of this year, politics will sway GBP as much or even more than economics. The path towards Brexit and trade agreements with the EU and the US is probably as important as the course of the UK economy, because the trade agreements will have such a big role in determining the future of the UK economy.

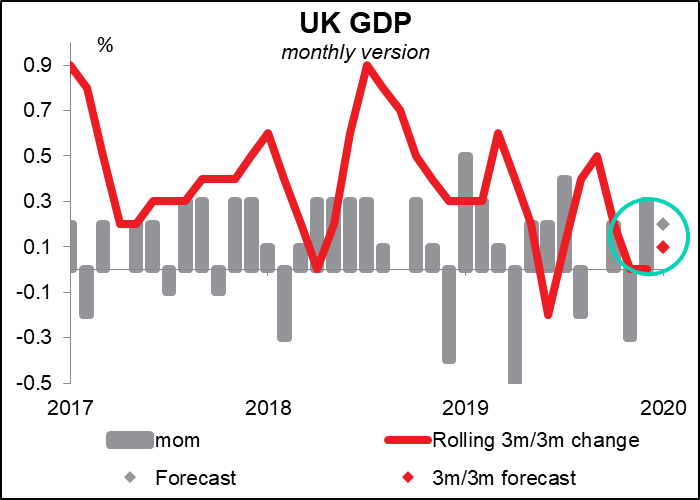

Also: Wednesday is “short-term indicator day” for the UK, with the monthly GDP figures, industrial & manufacturing production, and trade data coming out. As usual, the monthly GDP figures are likely to be the most important. They’re expected to show another month of growth, with the 3m/3m series moving up. This may be taken as a positive sign for the UK economy. However, the market impact if any is likely to be short-lived if any, as the Budget is of significantly greater interest.

ECB: look for something narrow

The ECB meeting Thursday is also likely to take some action. The problem is thinking of just what they can do. With the deposit rate at -0.50% already, a quantitative easing program of EUR 20bn a month, and a third round of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), the pedal’s to the metal already.

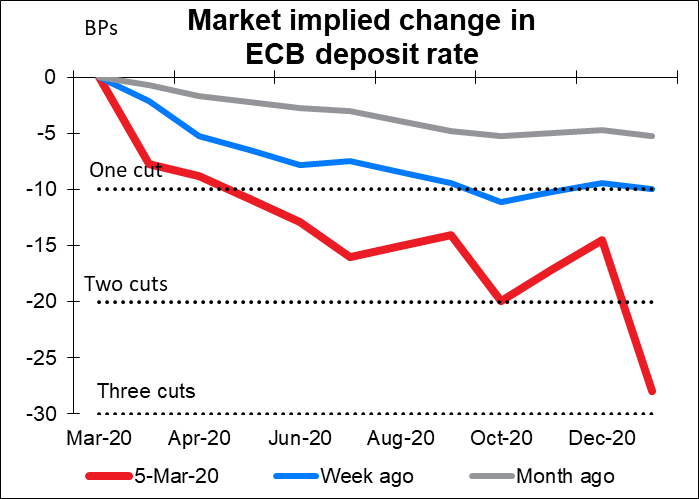

The key here is that ECB President Lagarde already stated that the Governing Council stands ready to take “appropriate and targeted measures”. “Targeted” is probably the key word here. I look for either a new round of TLTROs, or some adjustments to the existing ones to funnel them to SMEs in general or to companies particularly affected by the coronavirus, such as hotels and restaurants. There may well also be a rate cut, although that’s likely to be of more symbolic value than anything else at this point. The market is forecasting one rate cut this time or in April, another by October, and a good chance of a third early next year.

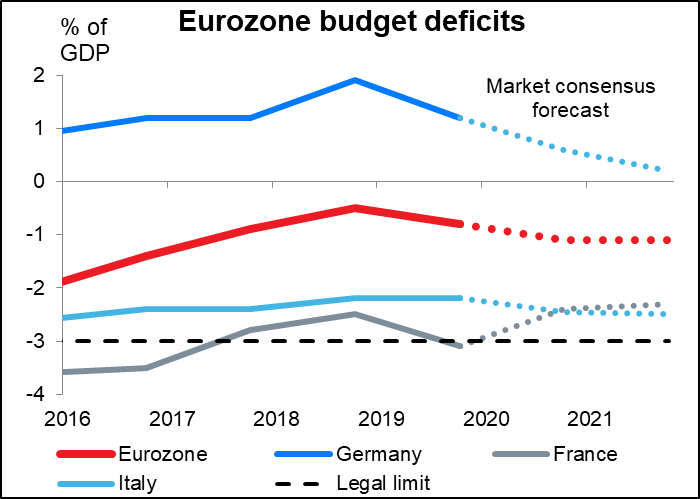

I would also expect the Governing Council to make yet another plea for fiscal policy to play more of a supporting role, but when we’re talking about fiscal policy in Europe we of course run up against the famous Kissinger Question: “Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?” (Although a bit of research turns up the surprising fact that Kissinger in fact never actually said this.) In this case it’s clearly Germany. And in fact Germany does in theory have room to expand its fiscal policy, although France and Germany are already dangerously close to the 3% limit. However, getting agreement from them is not so easy, particularly in the case of Germany. State loan guarantees or temporary tax holidays could be effective fiscal tools to help companies get over this period of reduced demand, but I wonder if governments can agree on such measures.

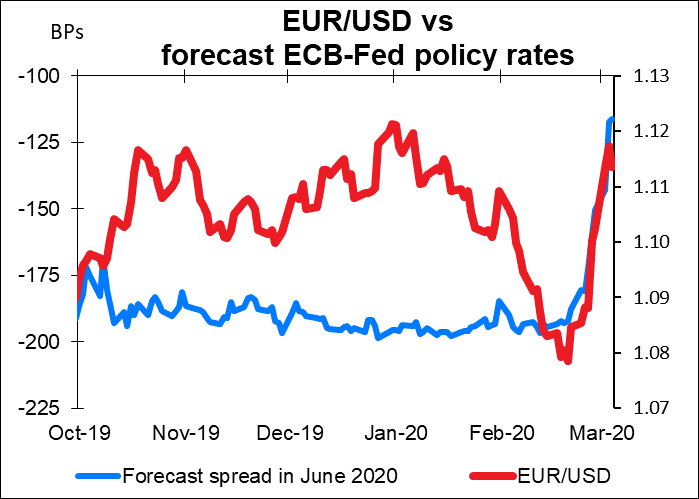

In any case, with the Fed having so much more room to cut rates than the ECB, the expected policy rate differential between the two zones is collapsing. That may drive EUR/USD higher still, at least temporarily.

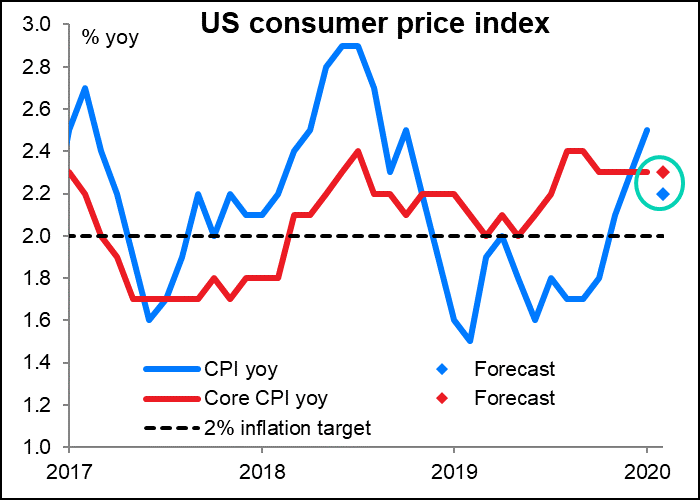

Finally, we get the US consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday. Ordinarily this would be a major indicator, even though it’s not what the Fed uses to gauge inflation – that’s the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators. However, in most people’s minds the CPI is inflation. Furthermore, the two are pretty close since they’re just different ways of measuring the same thing, and the CPI comes out about two weeks earlier than the PCE deflators.

This month however there are two reasons why the CPI isn’t going to be of that much interest. First off, the rate of increase of the core CPI, the more important of the two, is expected to be unchanged. That means no change in people’s expectations. Secondly, at the moment the Fed isn’t that concerned with inflation anyway. The virus count is the most important statistic for most countries nowadays. The Fed isn’t worried about inflation, it’s worried about a collapse of economic activity. Inflation being too low is just a symptom of that.