Rates as of 04:00 GMT

Market Recap

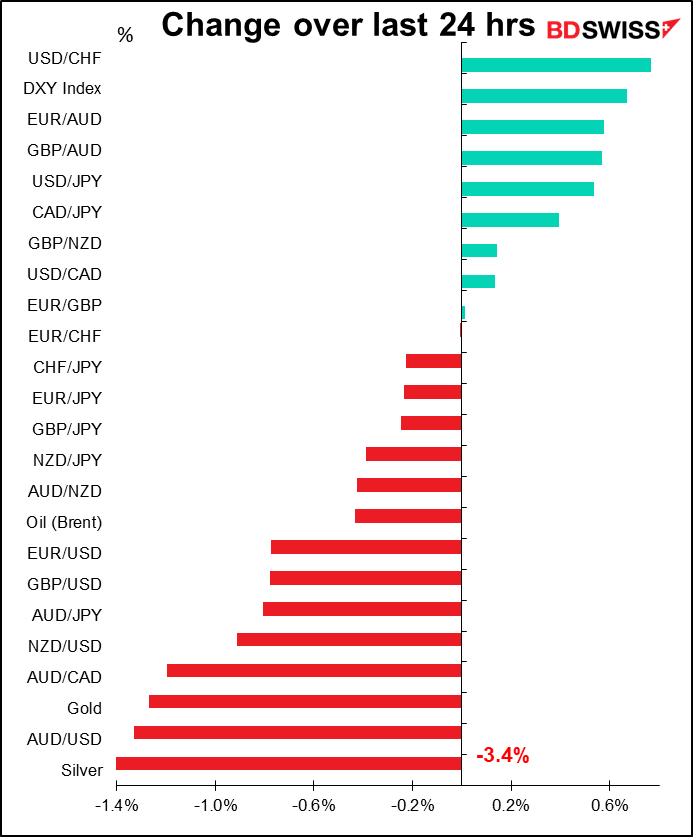

All those articles you may have seen earlier this year about the imminent demise of the dollar…

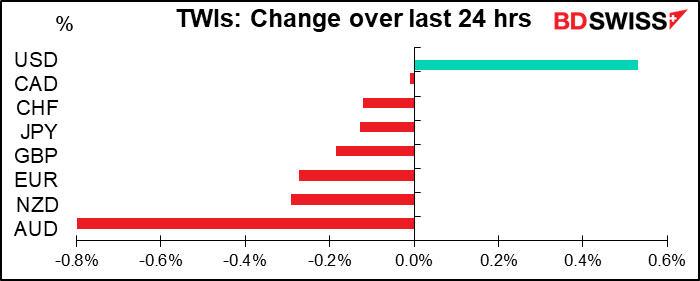

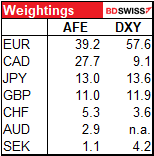

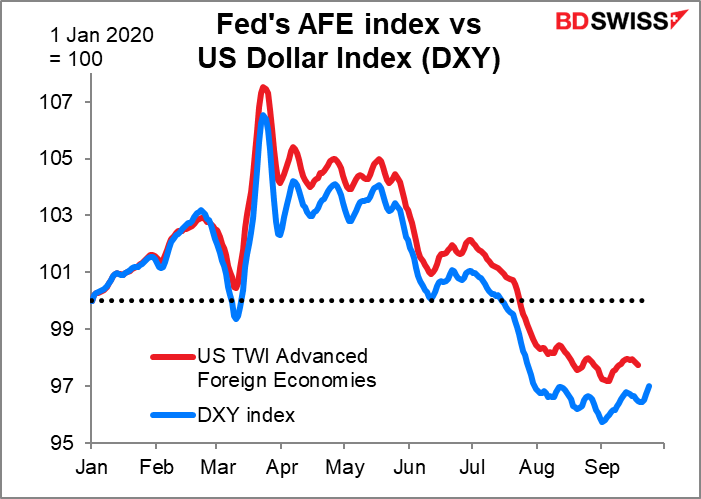

In fact, the dollar’s decline this year was never as great as people thought. Most people use the US Dollar Index (DXY) to gauge the dollar’s overall value, but this is a distorted ruler. It measures the dollar’s value against six major currencies, mostly EUR, JPY and GB, plus a bit of CAD, SEK and CHF. The Fed’s Advanced Foreign Economies Dollar Index (nominal) measures the same currencies (plus AUD) but uses different weightings and comes up with a different result.

The big differences are in the EUR and CAD. EUR accounts for 57.6% of the DXY but only 39.2% in the Fed index. On the other hand, CAD has a 9.1% weighting in the DXY and 27.7% in the Fed index, apropos of Canada’s position as the #4 trade partner of the US (after the EU, Mexico, and China). The weightings in the Fed index are revised every year, whereas the DXY weightings have been constant since it began in March 1973, with the exception of when the euro was created.

What was particularly interesting about yesterday’s dollar rally is that it wasn’t a “flight to safety” caused by a risk-off atmosphere in the markets. Quite the contrary, the dollar trended higher along with risk sentiment – the reverse of what we’ve seen recently. (In this graph, the red line is the S&P 500 mini-index futures and the blue line is the Deutsche Bank trade-weighted dollar index).

It may be that with the euro losing ground, the market is gradually changing its attitude toward the US currency. More and more countries are getting worried about their exchange rates (see comment about AUD below) and so market participants may be ree-evaluating the outlook for the dollar. I’d refer you to my Weekly Outlook, where I pointed out that once central banks have exhausted their conventional and even unconventional monetary policies, all that’s left is foreign exchange intervention (one way or another).

The dollar got a boost from Chicago Fed President Evans (NV), who somewhat undercut the Fed’s much-touted new monetary policy guidance by saying that the Fed’s new average inflation targeting approach doesn’t preclude tightening before inflation averages 2%. “We’ve sort of said we’re looking to get inflation up to 2%, and then after that, we could be raising rates and still have an accommodative setting of monetary policy,” Evans said. “And so, we could start raising rates before we start averaging 2%. It’s still — we need to discuss that.” That wasn’t the way most of us understood it, but then again I didn’t participate in the FOMC discussions so I would defer to his understanding.

On the other hand, AUD was the worst-performing currency after a speech by Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Deputy Gov. Debelle, who outlined “possibilities for further monetary policy action should the Reserve Bank Board decide that it is warranted.” Among the “potential policy options” that he mentioned was foreign exchange intervention.

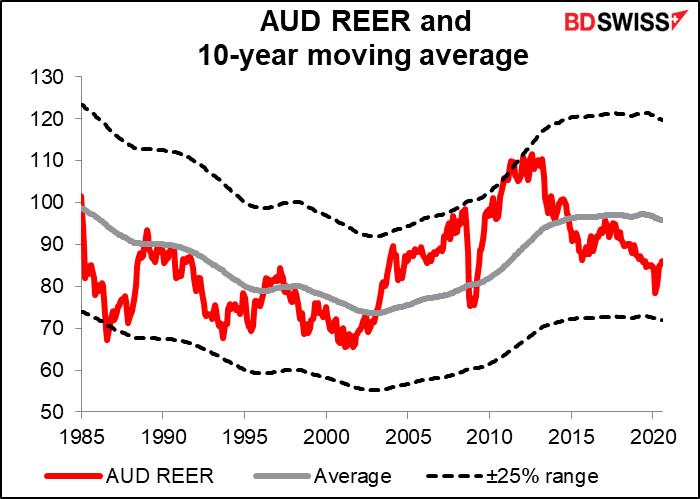

He didn’t seem too keen on it; he said, “with the Australian dollar broadly aligned with its fundamentals, it is not clear this would be effective in the current circumstances.” He also mentioned some problems that Switzerland had using that tool, and that one reason the AUD is strengthening is simply because the USD is weakening. “That said, a lower exchange rate would definitely be beneficial for the Australian economy, so we are continuing to watch developments in the foreign exchange market carefully,” he summarized.

He’s right that AUD is “broadly aligned with its fundamentals.” Using the OECD’s methodology, the currency is only about 6% overvalued vs USD, which is well within the normal range.

In fact far from being overvalued, the AUD’s real effective exchange rate (REER) is below its long-term average. It’s close to the level that has in the past been a floor for the currency, not a ceiling.

But of course what we’ve seen elsewhere, from the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank for example, is that central banks don’t always assess their currencies by looking at fundamental valuation. They sometimes just look at it relative to where it was a few months earlier. If the currency is strengthening then it’s bad, never mind if was undervalued before.

GBP had a volatile day. It gained after Bank of England Gov. Bailey pushed back on the market speculation about negative interest rates – he said there were still debates about the efficacy of negative rates, plus some practical constraints about implementing them. The currency also got a boost from news that Chief EU Brexit Negotiator Barnier would visit London today through Friday for informal talks amidst talk in the media of a “window of opportunity.” Nonetheless the currency ultimately ended lower after PM Johnson announced renewed restrictions, such as the requirement to wear masks in stores. The restrictions will last for six months.

Today’s market

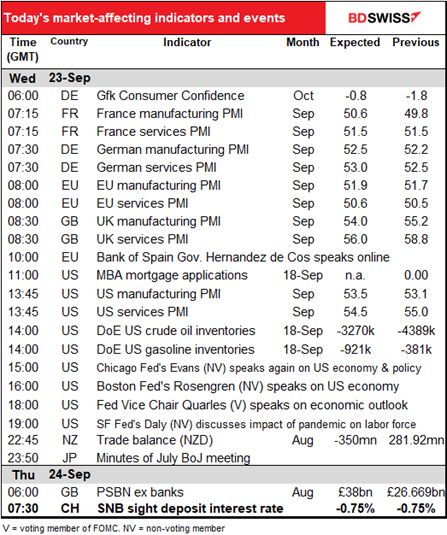

The main focus today will be on the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) from the major industrial countries. They’re listed in the table above in the order that they come out, but I think a better way to group them is by manufacturing and services. (Note that in the table below, the figures for Japan are the actual results.)

Looking at the forecasts, three things stand out: 1) the manufacturing PMIs are expected to decline (except France); 2) the UK and US service-sector PMIs are expected to decline, too; and 3) the Eurozone service-sector PMIs are expected to gain only slightly.

We can dismiss the expected fall in the UK and US service-sector PMIs as a function of the fact that they’re relatively high to begin with. Last month’s UK service-sector PMI for example was the highest it’s been since April 2015. A decline would still leave both comfortably in expansionary territory.

The expected fall in the manufacturing PMIs and the forecast tepid rise in the Eurozone service-sector PMI, which is barely north of the 50 “boom or bust” line anyway, are more worrisome. They suggest a stalling in the global recovery focusing on Europe. The particular weakness of the Eurozone PMIs could weigh on the euro.

By the way, this is also the message from Bloomberg’s “daily activity indicators” calculated from alternative high-frequency data. These showed a sharp rebound in June and July, but since then activity in the major economies has gone more or less sideways.

Aside from that, we have four Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members speaking today (five if you include Minneapolis Fed President Kashkari (V), who’s discussing “When Public Health Means Business” at the Harvard School of Public Health, so I didn’t include him on the schedule). Chicago Fed President Evans (NV) spoke yesterday so he’s not likely to say anything new. While Vice Chair Quarles (V) is the most senior person speaking and so normally would be the most important, I’m actually most interested to hear from San Francisco Fed President Daly (NV) discussing the impact of the pandemic on the labor force. That’s because it seems to me that the Fed is now focusing more on employment than on inflation as a policy goal. I particularly want to hear what they have to say about employment to get a sense of how long they think it might be – if ever — before the economy reaches any semblance of “full employment.”

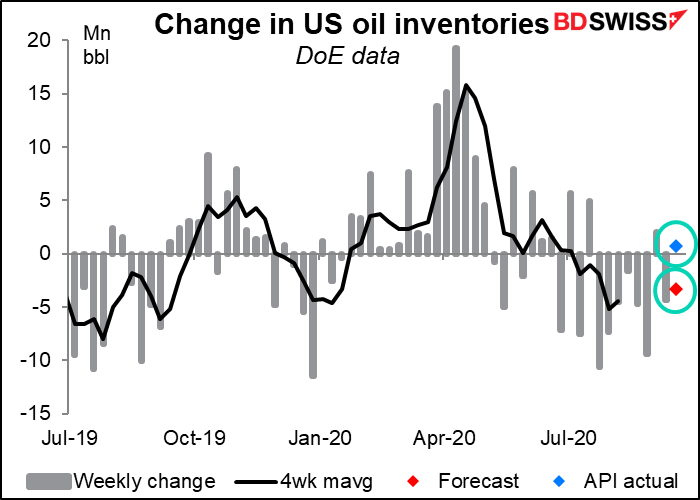

US crude oil inventories are expected to fall by 3.3mn barrels. Last night, the American Petroleum Institute (API) reported an increase of 691k barrels.

That could’ve been a big negative for oil. However, the API also announced an enormous drawdown of gasoline inventories of 7.7mn bbl, vs an expected drawdown of 921k. This was the biggest decline in about three years (since -8.428mn on 12 Sep 2017.)

Overnight, New Zealand announces its trade data. The figure isn’t seasonally adjusted, so I prefer to look at the implied average 12m average. That would rise under this forecast, which means the number should in theory be positive for NZD. But my guess is that global risk conditions are probably more important for the currency than the trade data.

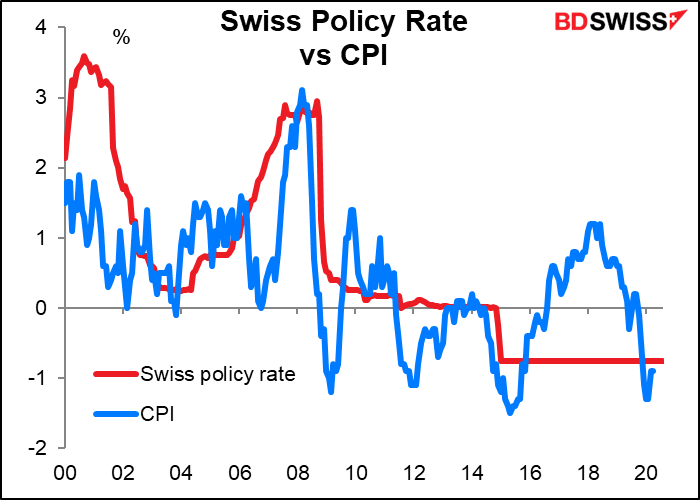

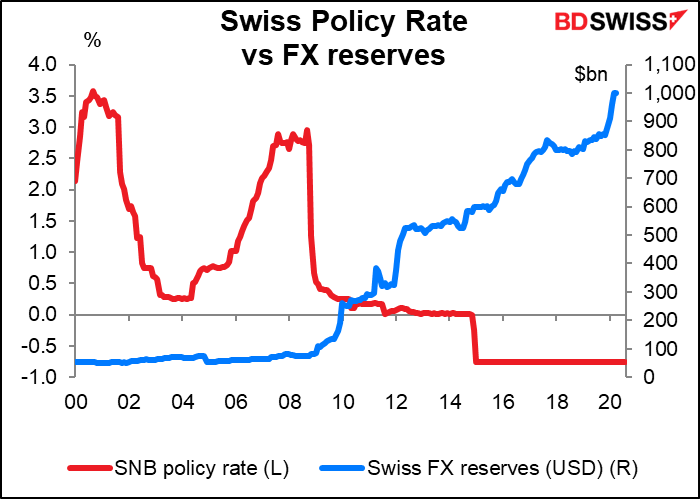

Then early Thursday morning, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) meets. I discussed their decision in detail in my Weekly Outlook, so I’ll just sum up here what I said: they haven’t changed policy in several years and they’re not likely to do so today, either. They lowered the interest rate on sight deposit account balances by 0.5 percentage point to −0.75% on 15 January 2015 and that’s it. I expect them to repeat some version of their statement from last time that “The SNB is keeping the SNB policy rate and interest on sight deposits at the SNB at −0.75%, and in light of the highly valued Swiss franc it remains willing to intervene more strongly in the foreign exchange market. In so doing, it takes the overall exchange rate situation into account.” No market impact is likely unless there’s some surprise move.

An argument could be made that the SNB should loosen further. On their website, they say, “The SNB defines price stability as a rise in the national consumer price index (CPI) of less than 2% per year…. Deflation – in other words, a protracted decline in the overall price level – is also regarded as a breach of price stability.” In fact the country has been in deflation since February and prices are expected to continue falling next year as well “before returning to positive territory in 2022 (0.2%).” Perhaps since they are forecasting stable prices in 2022, they can get away with keeping policy unchanged, although many people would argue that two years qualifies as a “protracted” period. My guess is that like the Bank of Japan, the SNB is probably doing all it can and really has no more bullets left to fire.