And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night…And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.

Edgar Allen Poe, The Masque of the Red Death

Well, I wouldn’t go quite that far, at least not yet. But as the center of the coronavirus pandemic moves out of China and into Europe, it’s looking grim here, folks. Cyprus, where I am now, is on lockdown and I can’t get home to my wife & daughter in Switzerland. I’m supposed to stay home most of the time, which is OK because there’s not much to do anyway; the whole country is shut, with only supermarkets, bakeries, pharmacies and gasoline stations open regularly.

The coronavirus does hold “illimitable dominion” over the financial markets. The virus has caused five shocks to the global economy, with devastating impact on the financial markets. With millions in lockdown, the global economy faces:

- A demand shock (as people stay home and stop buying stuff)

- A supply shock (as factory workers stay home and stop making stuff)

- A negative wealth shock (as stock & bond prices collapse)

- A credit shock (as credit ratings fall and banks become wary of lending); and

- An oil shock (exacerbated by the end of the OPEC+ agreement).

Stock and bond values have collapsed as worried investors rush into cash, exacerbated no doubt by margin calls throughout the system. Even the closing out of equity short positions made the problems in the money market worse, because investors who lend securities tend to invest the proceedings in CP and bank CDs. When they got their stock back, they had to sell the paper. Equity short sellers on the other hand tend to keep their money in T-bills, where demand is already excessive: rates on US T-bills are negative out to three months.

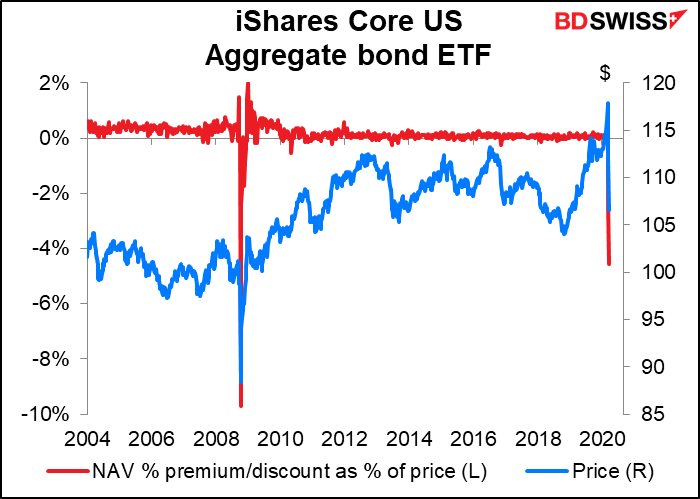

The result has been a torschlusspanik to liquidate everything: not only stocks but also supposed “safe haven” investments that are meant to be a refuge in troubled times, such as bonds and gold. For example, the iShares Core US Aggregate bond ETF, an enormous fund with some $68bn under management, has seen massive outflows second only to the 2008 crisis. The discount to net asset value, second-widest ever, is a result of a) the rush to get out of everything and into cash, and b) the lack of market-making capacity even in the major bond markets right now. I’ve seen reports that traders are having difficulty getting a price in the 10-year Treasury bond, which is basically like saying that Wall Street has shut down and gone home.

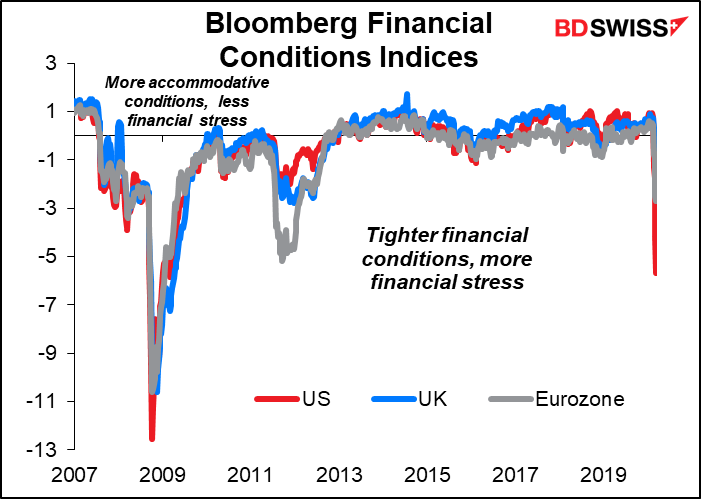

One reason for the freeze in markets is that as companies draw down their credit lines, banks’ balance sheets get used up, and less capital gets allocated to secondary activities such as market-making. The result is that spreads widen out if indeed markets are available. It’s not as bad as it was in 2008, but it’s getting there.

The gold market is another good example of the rush to liquidity. Gold prices have been plunging even though systemic uncertainty plus negative interest rates should be a winning combination for the yellow metal. But we’re seeing institutional investors selling the futures and ETFs to raise cash even as small retail investors clean the shelves of physical metal.

Meanwhile, with policy rates nearing zero, many people may believe that monetary policy “has reached its limit,” as to Austrian Central Bank Governor and ECB Council Member Robert Holzmann said Thursday morning. Three hours later, the ECB announced EUR 750bn of QE – proving that no, monetary policy hasn’t reached its limit. Once they reach the zero bound or effectively so, central banks – such as the Fed, Bank of England and RBA as well as the ECB – are increasing or instituting quantitative easing programs. That adds liquidity to bond markets and helps to alleviate the financial disruption.

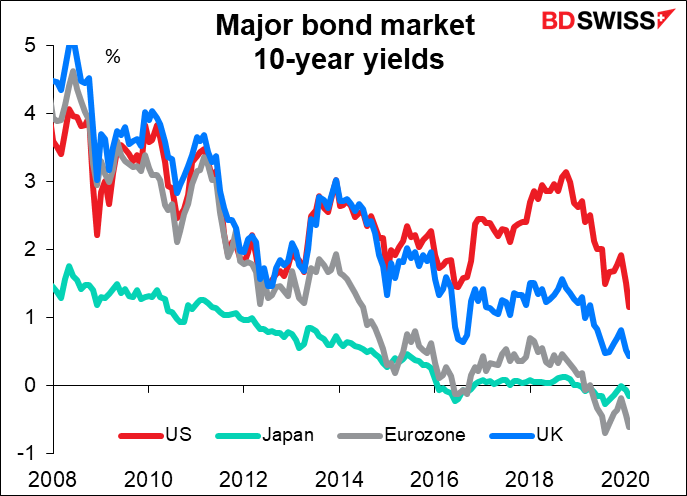

How is all of this affecting the FX market? One of the ways investors adapted to the zero interest rate environment around the world was to invest in higher-interest-rate products in other currencies (i.e., carry trades). Given that US interest rates were so much higher than other countries’ rates during much of this period, a lot of life insurers, pension funds and other investors bought US assets. They often funded these investments through the dollar swap market.

Now that they have to roll over these swap lines at times when banks are balance-sheet-constrained, it’s caused a rush for dollars that has bid up the dollar’s price.

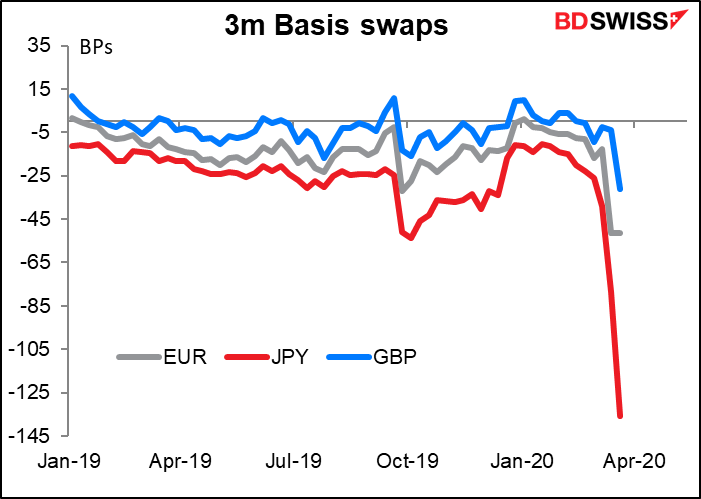

Notice in the graph above how much lower Japanese yields have been compared to US yields. That created a great incentive for Japanese borrowers to invest in USD paper. Now notice below how while all the FX swap rates have blown out recently, the USD/JPY swap rates have blown out far and away the most. Guess why?

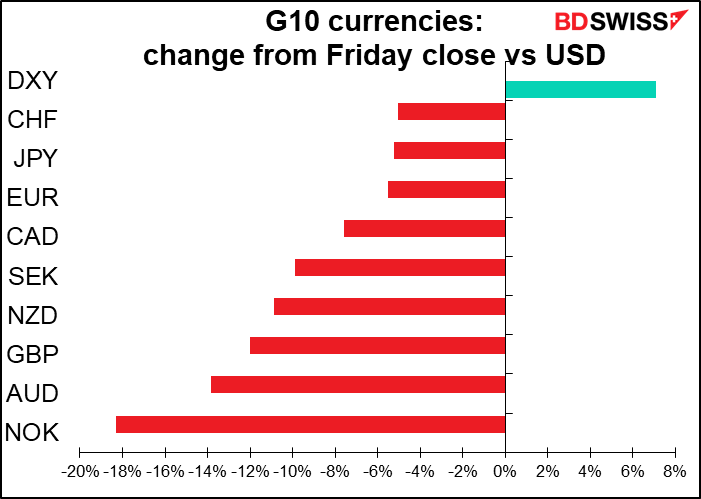

It’s also an interesting question how much worse the situation is because of reduced risk-taking among banks and machines replacing human traders. As computers sell to computers, we’ve seen currencies collapse in a way that was, well, not unthinkable but certainly unusual before. The recent plunge in NOK and GBP stand out in this respect. They’re more typical of emerging-market currencies facing a “sudden stop” than G10 currencies.

This graph shows the percentage change in currencies since 8 March. Note how MXN/USD (black line) and NOK/USD (green) have traded pretty much together, while GBP/USD (blue line, inverted) has done about as well as USD/BRL (pink).

The RBA and Norges Bank said that they’re prepared to intervene in the FX market either to prevent disorderly markets (RBA) or to stem the slide in their currency (Norges Bank). The Swiss National Bank (SNB) already intervenes as a matter of policy. I wouldn’t be surprised if other central banks started talking about intervening as well.

Hoping to stem the slide, the Fed established temporary dollar swap lines with nine additional central banks (AU, BR, KR, MX, SG, SE, DN, NO NZ) in addition to the five that it had previously (EU, JP, GB, CA, CH). These are the same central banks that it established temporary swap lines with back in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis.

It’s clear that gradually, officialdom is “getting it.” Central banks are stepping up not only to backstop the banks, but also to fill in as “market-maker of last resort” to keep the markets liquid. Governments are setting up facilities to lend money directly to companies and the unemployed. Even in the US, where the Republican Party would literally prefer that people die rather than get medical insurance from the government, they’re talking about giving money directly to individuals. “Social distancing” is fast becoming the norm in much of Europe and, I hope, will spread to the US. We should be over this crisis eventually. Even in China, the epicenter of the disaster, life is starting to return to normal, only three months or so since the virus was first discovered.

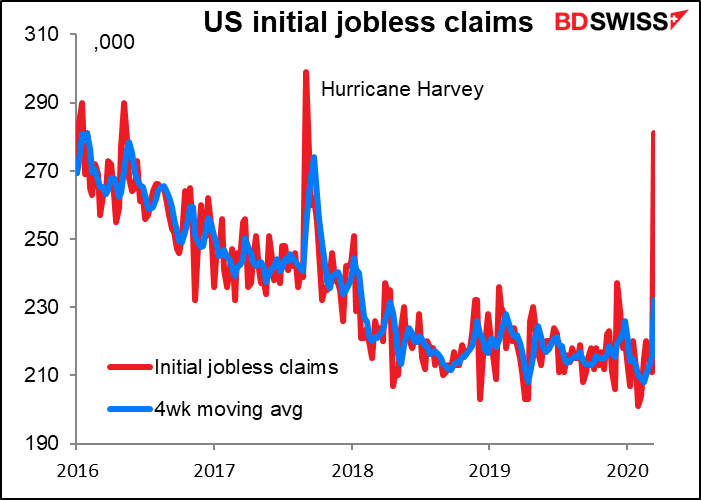

(My guess is that the change of strategy among the Republicans was due less to a change in heart than to a fear of going into an election with the stock market crashing, unemployment soaring, and everyone’s Grandma dying. Yesterday’s intial jobless claims for the week ended 14 March, the highest in four years if we exclude the blip caused by Hurricane Harvey, were just the beginning. SurveyUSA estimated that 9% of working Americans (14mn) far have been laid off so far as result of the virus and that 1 in 4 workers have had their hours reduced.)

The big question for me is, how long will the global demand for dollars win out over the lackadaisical approach in the US to this disaster? Many Americans still doubt the severity of the virus or think that it’s only serious if you’re elderly or have some underlying conditions and therefore aren’t taking any particular precautions. It’s only a matter of time in my view before the virus dies down in Europe and the US becomes the new epicenter. Until then and as long as Japanese life insurers have to refinance their US Treasuries and whatever else in the USD/JPY swap market, the dollar is likely to remain bid. But once that bid is filled and US fatalities start rising…watch out.

Coming week: Bank of England, preliminary PMIs, US, UK & Japan inflation data

There’s only one major central bank meeting on the schedule, the Bank of England on Thursday, and that’s liable to be rather anti-climactic after they already cut rates and upped their QE program in an emergency meeting yesterday. I think the most interesting part of that meeting will be reading the minutes to get a clearer idea of their thinking, especially with the new BoE Gov. Andrew Bailey at the helm.

Of course we’ve discovered recently that just because meetings aren’t on the schedule doesn’t mean they can’t happen. Unscheduled meetings seem to be the “in” thing among central bankers nowadays.

At this point there’s only one speaker on the schedule for the week, RBA Assistant Gov. Kent, who’s appearing at an industry conference (assuming that it takes place). Two talks by regional Fed presidents were cancelled. I would guess this will be part of the “new normal” going forward: fewer and fewer speeches and press conferences.

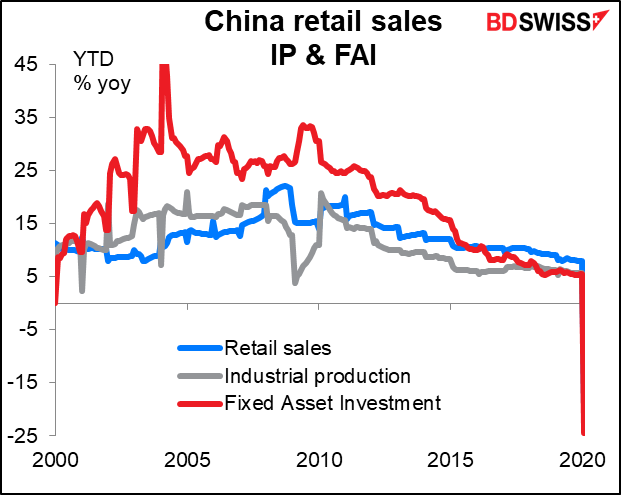

Is it worth going over the indicators that are coming out next week? I think we can say with pretty good assurance two things: 1) they’ll be bad, and 2) the next month’s will be even worse. On the other hand, what we can’t say is exactly how bad they’ll be. The example of China during the worst days of its virus shut-down showed us just how bad things can get, with unprecedented declines in activity and sentiment.

Thus any “forecasts” this month are mostly just guesses, and we can expect a lot of surprises. My guess is: mostly negative surprises.

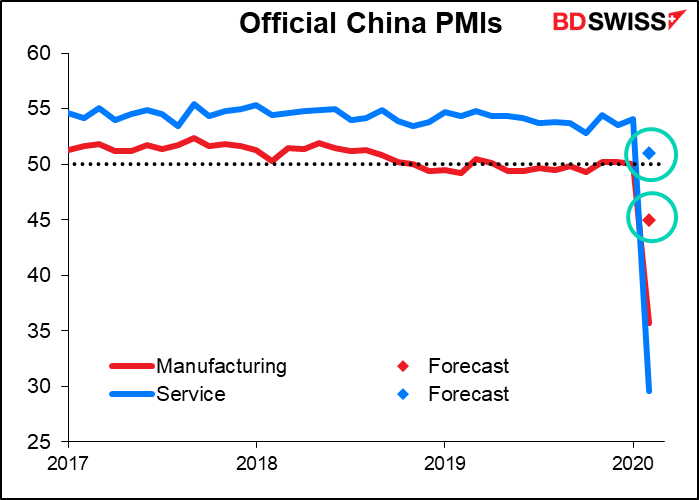

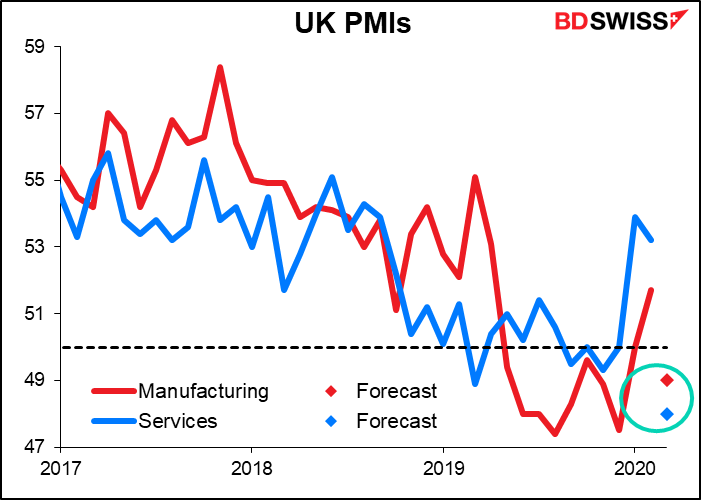

The main topic of interest will be the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major countries on Tuesday. Just to remind you what the Chinese PMIs for February were, the manufacturing PMI was forecast to fall from 50.0 to 45.0; it plunged to 35.7. The service-sector PMI was expected to fall to 51.0 from 54.1; it plummeted to 29.6. The difference is that now economists know what happened in China so they may be able to make somewhat better forecasts, but still, to map that onto other countries will be difficult.

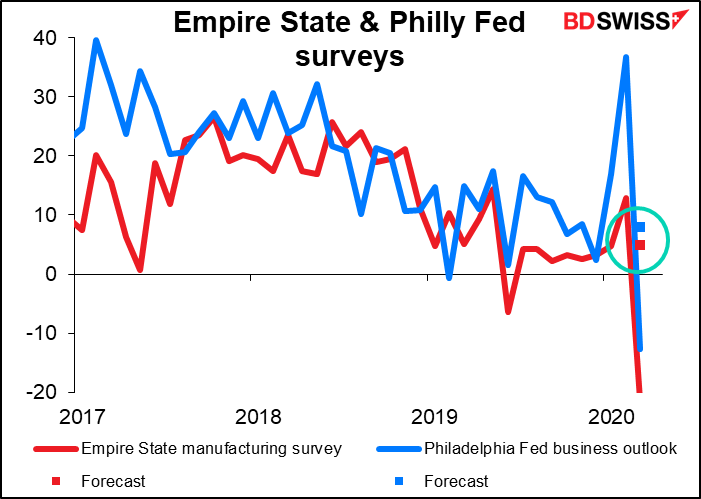

Lest you think that China is an outlier, may I remind you of this week’s Empire State and Philly Fed surveys: the expected for the Empire State was 4.9, the actual was -21.50; for the Philly Fed, it was 8.0 and -12.7. So basically, no one has any idea of what any activity- or sentiment-related indicator will be.

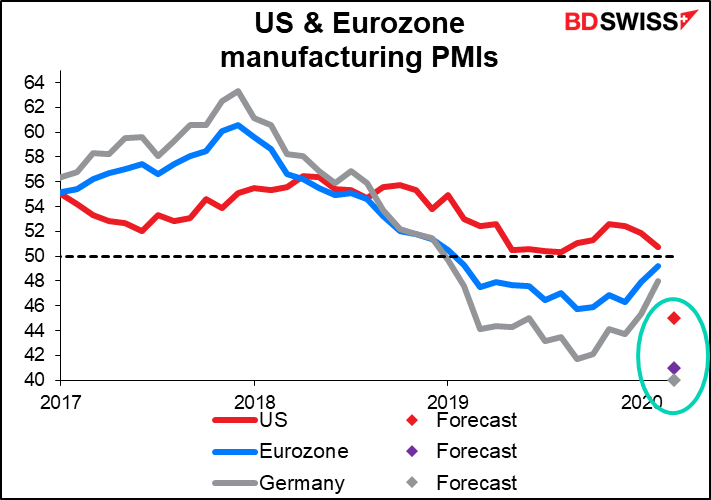

Having said that, the Eurozone PMIs are expected to fall well into contractionary territory, although nowhere near as much as China did. The Eurozone manufacturing PMI is forecast at 41.0, down from 49.2. So from mildly contractionary to wildly contractionary.

The US manufacturing PMI is expected to fall to 45.0 from 50.7. Bad, but not as bad as Europe.

The UK meanwhile is expected to get off easy. Their manufacturing PMI is forecast to fall only to 49.0 from 51.7. If that turns out to be correct, I would rate it as close to miraculous.

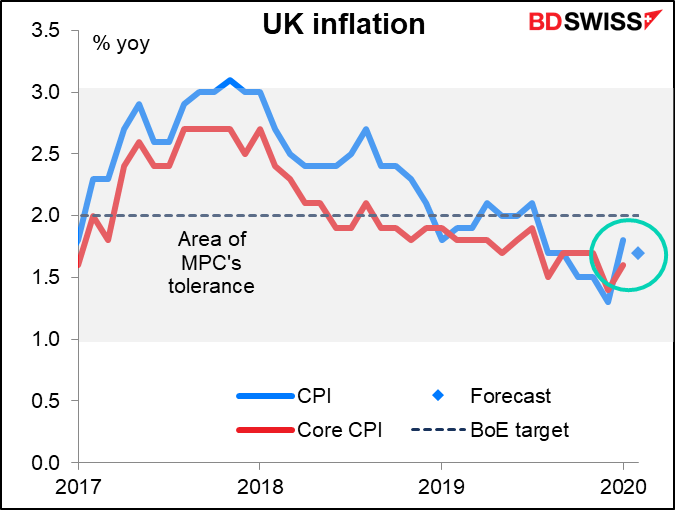

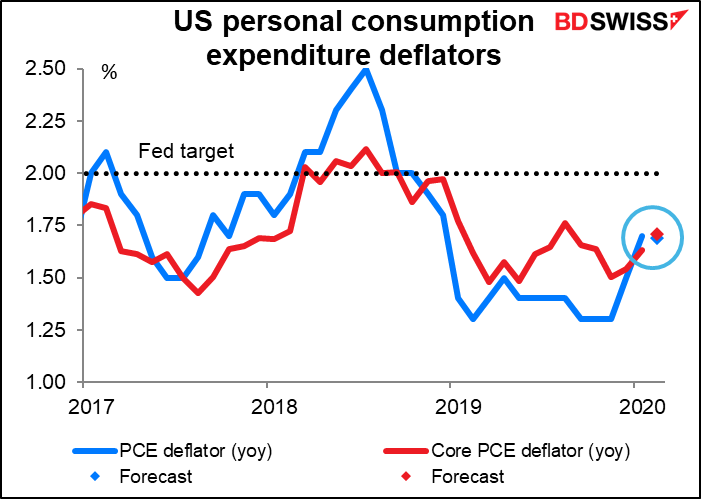

There is also inflation data coming out from the UK, Japan and US that ordinarily would be important, but nowadays is just an FYI item. Monetary policy is not going to change any time soon no matter what the inflation data shows. Rates can hardly get lower even if inflation slows, and while the virus is wreaking havoc with economies no central bank is going to raise rates. (In fact, while so few people are out shopping it’s highly unlikely that prices will rise anyway, unless of course it’s due to reduced supply as supply chains are interrupted or suppliers are shut down.)

For what it’s worth, the yoy rate of increase in the UK consumer price index (CPI), out on Wednesday, is expected to slow a bit, but to remain quite close to the Bank of England’s 2% target. No forecast for core inflation is available.

Other important UK indicators out during the week include retail sales on Thursday.

In the US, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator and the core PCE deflator, are released on Friday along with the personal income & spending figures, as usual. Both the PCE deflators are expected to be +1.7% yoy. That would be an unchanged pace for the headline figure and a bit faster for the core rate.

Other US indicators worth noting during the week include durable goods on Wednesday and the final revision of Q4 GDP on Thursday.

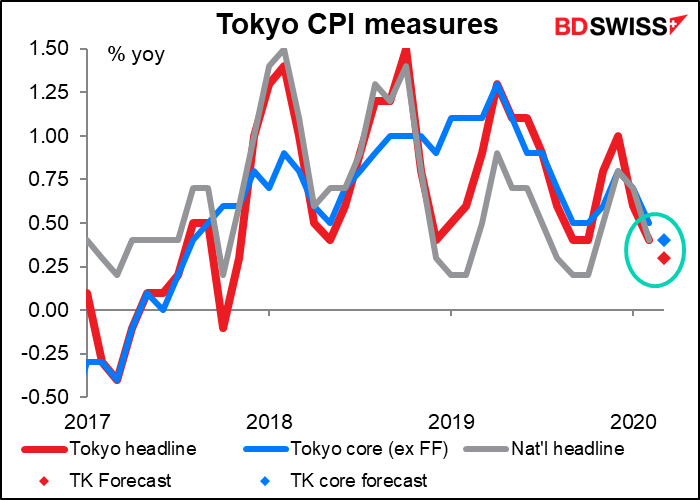

Japan announces the Tokyo CPI on Friday morning. Inflation is expected to slow a bit, but that’s not going to make the BoJ move.