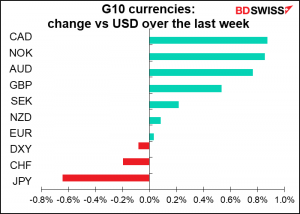

We had the Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank this week. Next week, we get three more major central banks: the Fed (Wednesday), the Bank of England (Thursday), and the Bank of Japan (Friday). (Norges Bank also meets on Thursday, but I don’t cover Norway. It’s expected to keep its rates steady, just in case you’re interested.)

The Fed and Bank of England meetings should be fairly routine, while the outcome of the Bank of Japan meeting looks to be unusually complicated and uncertain.

Fed: focus on forecasts

I expect the meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to be pretty boring. I don’t expect much if any change in the statement following the meeting, except perhaps an upgrading of the economic outlook and an acknowledgment that the US vaccination program, which is proceeding ahead of schedule, has reduced the downside risks to the economy. Nonetheless central bankers are by nature a cautious lot and I don’t expect them to break out the verbal champagne just yet.

The most important part will be the new Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), which has the economic and rate forecasts of the FOMC members. The updated forecasts will now take into account the passage of the Biden Administration’s $1.9tn fiscal support package as well as the faster-than-expected rollout of the vaccine. They should be revised substantially upwards. Many Fed officials have said recently that vaccination would lead to much stronger growth this year and that downside risks had abated.

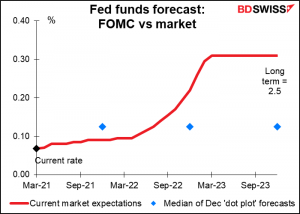

Comparing the December forecasts with today’s market forecasts, the market is more optimistic than the Fed was with regards to growth this year and next but more pessimistic with regards to unemployment.

The market expects inflation to go back to the Fed’s 2% target level earlier than the Fed does, but remember that just going back to 2% is no longer enough to justify tightening. In its recently revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, the Fed said that “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time” (emphasis added). Since inflation as measured by the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, hasn’t been over 2% for one consecutive year for any sustained time since 2006, I think we would have to see higher forecasts than that to justify tightening.

I expect the Committee to remain unconcerned about inflationary pressures. Officials have noted that they are not concerned about a temporary rise in inflation this year driven by base effects or temporary bottlenecks, so long as underlying inflationary pressures remain subdued. Several of the regional Fed Presidents have said that they don’t expect the $1.9tn fiscal support package to cause the economy to overheat. Furthermore, many FOMC members have pointed out that when the unemployment rate got down to a 50-year low of 3.5% before the pandemic there was still no sign of overheating in the labor market.

On the other hand, Treasury Secretary Yellen has said that the Biden Administration’s recent fiscal support package could allow the labor market to recover to full employment by the end of next year. That’s significantly better than what the Fed forecast in December. We should pay particular attention to their employment forecast.

The notorious “dot plot,” with the Committee members’ forecasts for the end-year fed funds rate, is likely to remain unchanged for this year and next, but what about 2023? In December, there were 12 dots at 0.125%, i.e. unchanged, three at 0.375% (i.e., one rate hike during the year), one at 0.625% (two hikes), and one optimist at a very aggressive 1.125% (probably also responsible for the one dot expecting a rate hike in 2022.) If more people expect a hike in 2023, that will only confirm that once again, the Fed is moving toward the market’s view of things, rather than having the market come into line with the Fed’s way of thinking.

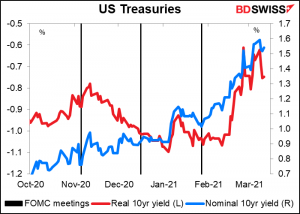

Aside from that, the important thing will be what they say about the recent rise in long-term rates and what if anything they plan to do about it. You can see from the graph how 10-year yields have risen since the last meeting in January – from 1.02% to 1.54%. This has not been due entirely to higher inflation expectations – on the contrary, real yields have risen alongside nominal yields. They could if they wanted to take several steps to deal with this problem, such as a) increase their bond purchases, b) “twist” them by buying less in the short end and more in the long end, or c) in the extreme, instituting “yield curve control” (YCC) as Japan and Australia have done and setting a target for the long end of the market.

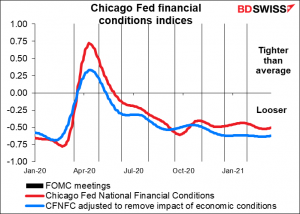

In the event, I doubt if they will do anything, and I expect Fed Chair Powell to remain sanguine on this point in his press conference. Looking at what Committee members have said recently, many indicated they are not concerned about higher yields since broader financial conditions remain accommodative. Several said that they would be concerned by a persistent tightening in broader financial conditions or disorderly market conditions, but we haven’t seen those yet. Quite the contrary – the Fed’s own gauge of financial conditions shows that they’re still looser than average.

I don’t expect any change in their view on asset purchase, either. Recent commentary from officials has emphasized that monetary policy will remain accommodative and that asset purchases will continue at least at their current pace for “some time.” Fed Presidents Daly and Bostic noted that they do not expect to begin tapering asset purchases this year, and Fed Presidents Bullard and George said it is too early to discuss tapering.

Market implications: An upgrading of economic forecasts together with no pushback against the market’s view on yields may spark a further sell-off in bonds. I expect that would be likely to push stocks down and push USD up.

Bank of England still on hold

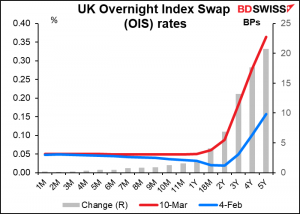

The Bank of England should be even less interesting, I’m afraid. The market thinks maybe there could be a 10 bps hike in rates in two years and a full 25-bps hike sometime between three and four years from now. Mark your calendars today! Meanwhile, the possibility of negative rates, which for some time has been the Sword of Bailey hanging over the market, has been priced out. So, what’s an analyst to do?

At the last Bank of England meeting, on Feb. 4th, the statement following the meeting wasn’t particularly riveting but the minutes got the markets buzzing when it said the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided, “it would be appropriate to start the preparations to provide the capability to (implement a negative Bank Rate) if necessary in the future.” No matter how much they protested that the MPC “did not wish to send any signal that it intended to set a negative Bank Rate at some point in the future,” of course having one available makes it a possibility, while as long as it was unavailable it was an impossibility.

However, since then the vaccination rollout has gone better than anyone dreamed for any activity carried out by Boorish Johnson et. al. and the likelihood of negative rates has been taken off the table. “There is a growing sense of economic optimism in markets and in consumer and business measures,” Gov. Bailey said Monday. And a month ago, (Feb. 11), Chief Economist (and chief MPC Hawk) Haldane said that “The recovery should be one to remember, after a year to forget. A year from now, annual growth could be in double-digits.”

With Bank Rate at 0.10% and five months to go before it can be made negative, there’s little room to cut rates, and a rate hike right now is unthinkable. As for asset purchases, in testimony to the Treasury Committee, Deputy Gov. Broadbent said that the BoE would review the pace of gilt purchases but that “it would take significant news” for them to alter the pace of purchases. No such significant news has occurred since the last MPC meeting that I can discern. That doesn’t leave the MPC with much to play with, does it?

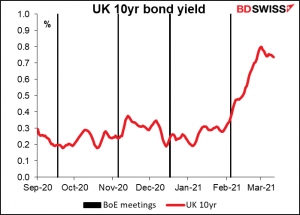

Accordingly, we will once again just be looking to see what they say about the likely pace of the recovery and any comments about higher bond yields, which have hit the UK Gilts market too.

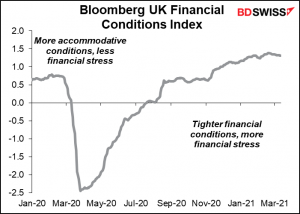

Other central banks have noted that they would only be concerned about higher bond yields if the higher yields start to impinge on financial conditions. The UK is still far away from that unhelpful state. If the Bloomberg UK Financial Conditions Index is a reliable metric, financial conditions are still over 1 standard deviation looser than normal for the pre-crisis period (1999 to July 2008). So, no need for the Bank to get upset about higher yields yet, either.

In short, I expect a relatively anodyne statement with perhaps a more optimistic tone but no clear policy signal and another 9-0 vote to keep policy unchanged. An upgrade in the tone could support the pound somewhat.

Bank of Japan: review time!

This is probably the most highly anticipated – and unpredictable — Bank of Japan Policy Board meeting since it introduced Yield Curve Control back in 2016. Nobody expects the BoJ to substantially change its monetary policy during the remainder of the Anthropocene Era. However, at the December Policy Board meeting they said they would “conduct an assessment for further effective and sustainable monetary easing… The Bank will assess various measures conducted under [the current monetary]framework and make public its findings, likely at the March 2021 Monetary Policy Meeting.” So, Friday is the day for the big reveal party when they will “recalibrate” their measures, as the ECB would say.

The review is likely to address three major themes, which Deputy Gov. Amamiya laid out in a speech on Monday. These are:

● More effective purchases of equity Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs)

● Alleviation of the adverse side-effects of the negative interest rate policy (NIRP); and

● Better functioning of the Japanese Government Bond (JGB) market

Let’s deal with each in turn

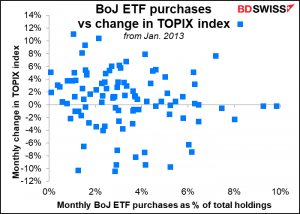

More effective ETF purchases: Several Board members have alluded to this issue already, so it’s fairly uncontroversial. The BoJ is committed to buying a net JPY 12tn in ETFs and JPY 180bn of Japan real estate investment trusts (J-REITS) a year, maximum. Historically it has tended to buy without regard to whether the market was rising or falling (see graph). Probably the BoJ will curb its ETF buying during normal times and increase its buying when the stock market is “volatile” (although strictly speaking volatility simply refers to the standard deviation of prices, among Japanese officials, “volatile” is a euphemism for “falling.” No one ever refers to rising markets as “volatile.”)

The Mainichi newspaper reported that the BoJ is likely to eliminate its annual target to buy JPY 6tn of ETFs while keeping an annual ceiling of JPY 12tn. This is likely to give more flexibility to refrain from buying when the market is already going up.

Alleviation of NIRP side-effects: Bank earnings are hurt because of the compression of their Net Interest Margin (NIM), the difference between what they borrow at and what they lend at. With 10-year yields pegged to around zero, it’s hard to make any spread at all. Also, insurance companies and pension funds are having a hard time meeting their asset/liability management targets, because they can’t get any interest income from their bond investments.

This means the BoJ would have big problems if it ever tried to lower interest rates further. But it’s still committed to reaching its 2% inflation target sometime and its forward guidance still holds out the possibility of lower interest rates (“…will not hesitate to take additional easing measures if necessary, and also it expects short- and long-term policy interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels). Given the problems that even the current level of rates creates, this threat of even lower rates isn’t credible. It therefore has to find some way to alleviate these side-effects so that it can carve out room to ease policy further if necessary.

Possible solutions include expanding its lending to financial institutions at negative rates or revising its three-tier structure for bank reserves to pay banks higher interest on reserves balances. These are pretty technical moves that wouldn’t have much impact on the FX market.

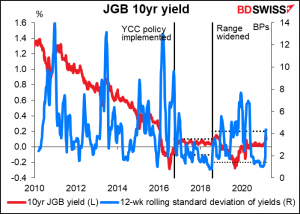

Better functioning of the JGB market: This one is dear to my heart. I started out in the financial world as a JGB analyst. This was back in the days when the benchmark #89 bond was the most actively traded real financial instrument in the world (as opposed to derivatives). Sometimes this one bond traded something like 4% of the country’s annual GDP in one day. Now, the market sometimes goes entire days without a single bond trading. The problem is that the BoJ has instituted Yield Curve Control (YCC), which means keeping the 10-year bond within a range of ±20 basis points of zero. With overnight rates at -0.3%, it means the yield curve can barely change. So why trade bonds? Just buy and hold, eventually selling to the BoJ for a small profit.

Leaks to the press had suggested that this problem would be addressed by widening the range to ±30 bps, which doesn’t seem like much when some other countries’ 10-year yields have gone up by 80 bps or so in the last few weeks. But BoJ Governor Kuroda Friday put the kibosh on even that modest idea. Speaking to the House of Representatives’ Committee on Financial Affairs, he said that “the Bank does not think it is necessary to expand the range” and “we are not at all close to the stage of expanding it to a range of plus or minus 0.3%, and extensive discussion is still required at this point.”

That would seem to be that, except Deputy Gov. Amamiya Monday revived the idea just three days later when he said on Monday that “Yields can go up and down more as long as it doesn’t hurt the effects of monetary easing.” “Although significant fluctuations in interest rates could lead to undesirable consequences, fluctuations within a certain range could have positive effects on the functioning of JGB markets without losing the effects of monetary easing,” he said.

The market is waiting to see how the Policy Board squares this circle, probably by defining “significant fluctuations” and “a certain range” quite vaguely, thereby leaving lots of wiggle room. In fact, the band has never been spelled out in black & white specifically; the policy statement simply says “the yields may move upward and downward to some extent mainly depending on developments in economic activity and prices.” Only Gov. Kuroda specified the range in his press conference following the Monetary Policy Meeting when the range was established and then again when it was widened in July 2018. We will probably get some vague waffle on this topic in the statement and will have to wait for the press conference to find out what it means.

Market implications: Given the current trend of higher bond yields around the world, this is the most important part of the announcement for the FX market. Higher JGB yields would make foreign yields less attractive and therefore slow the yen’s decline. On the other hand, keeping them in their current ±20 bps straightjacket means a widening interest-rate gap with other countries that’s a prescription for a weaker currency.

Other indicators out during the week: US retail sales, Japan & Canada CPI, Australia employment, NZ GDP

In addition to the three central bank meetings, there are several important economic indicators coming out during the week.

US retail sales on Tuesday is the biggest US indicator. It’s expected to be down slightly, which would be no surprise after the unexpected 5.3% mom surge in the previous month, thanks to the arrival of stimulus checks combined with growing vaccine distribution. Besides, with $1,400 checks coming down the pipeline to most Americans, expectations for spending in March and April are probably pretty good. I think a low number would be brushed aside as just a temporary interruption before the pandemic support checks appear and spending takes off again.

Other US indicators coming out include the Empire State and Philadelphia Fed business sentiment indices (Monday and Thursday, respectively). These will be the first indicators for March and so as usual will be closely watched. Also housing starts on Wednesday. And of course, the dreaded weekly jobless claims.

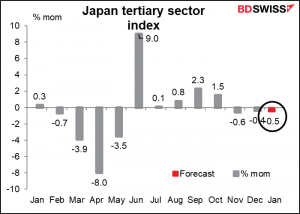

Japan releases its machinery orders and tertiary sector index on Monday, trade balance on Wednesday, and national CPI on Friday.

The tertiary sector is expected to contract for the third consecutive month, which would be discouraging for the Japanese economy except it would do no more than confirm the story told by the service-sector purchasing managers’ index (PMI) and the much-ignored Eco Watcher’s survey, which are both also showing a contraction of the service sector. The national CPI is expected to accelerate a bit but to remain in deflation.

Canada releases its housing starts on Monday, CPI on Tuesday, and retail sales on Friday. No forecasts available yet. In any event, CAD seems to be swayed more by oil prices recently than by domestic economic indicators.

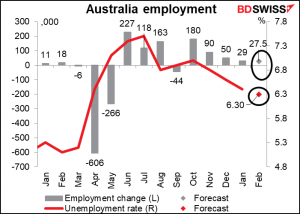

Australia releases its employment data on Thursday and retail sales on Friday. Like many central banks, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is probably putting more weight on employment nowadays than on inflation. The figures are expected to show another month of higher employment and a lower unemployment rate, which could help to boost AUD.

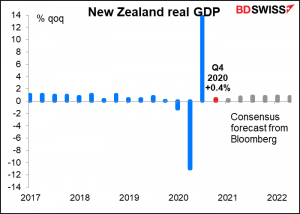

New Zealand is among the last of the industrial countries to release its Q4 GDP even as we are two weeks into Q2 of the following year. After two quarters of dramatic changes, Q4 is expected to show a boringly normal rate of increase of +0.4% qoq.

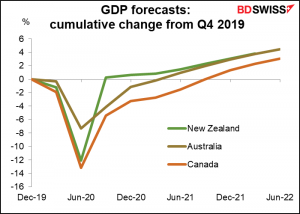

Looking at the three commodity currency countries, New Zealand has recovered faster than Australia, but Australia is expected to catch up by the end of the year. Meanwhile Canada, which has had much more of a problem with the virus than either of those two countries, has lagged behind.