Markets are getting very excited at the prospect of countries coming out from under lockdown. Investors are assuming that as countries come out of lockdown, economies will recover and we’ll get back to some semblance of normal, what might be a “new normal.” How much impact is it likely to have?

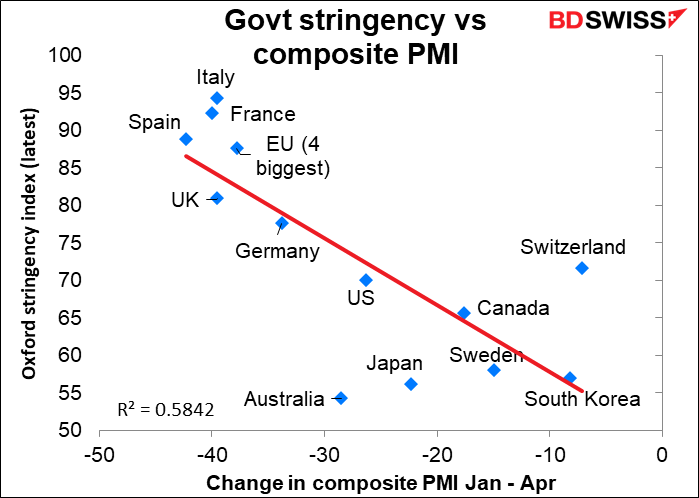

We can make some estimates of that by looking at how the lockdown has affected countries so far and working backwards – assuming that those countries with the most severe lockdowns will get the biggest bump as they come out of lockdown.

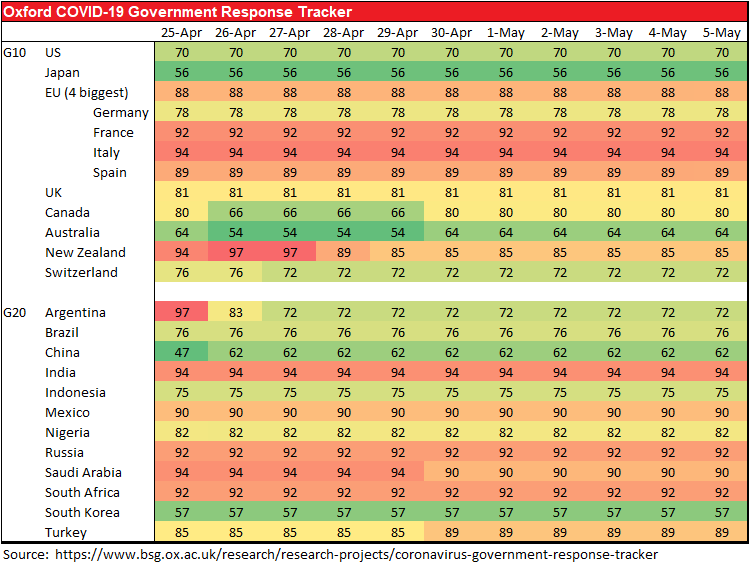

We can get an idea of the severity of the lockdowns in each country through the Oxford Government Response Tracker. Researchers at Oxford University have made an index of 12 indicators of government responses to the virus. Eight of them record information on containment and closure policies, such as school closures and restrictions in movement, while five record health system policies such as the virus testing or emergency investments into healthcare. They then aggregate the policy scores into a common “Stringency Index.” The results are given below for the countries belonging to the G10 plus the G20, plus one or two others, which cover about 75% of world GDP.

The impact of the lockdown on the economies is quite clear. The following graph shows the latest stringency index vs the change in each country’s composite PMI (or manufacturing if no composite is available) between January and April. It’s quite clear: the harsher the lockdown, the worse the impact on the economy.

Many countries are starting tentatively to lift their restrictions. In Europe, Italy, Germany, France, Spain, Poland, Greece and Belgium (at least) have started to ease up on some of the restrictions. Elsewhere, India, Nigeria and Lebanon are loosening up as well.

“It is necessary to live with the virus,” said French President Macron, because of the economic damage caused by shutting everything down. Still, he said, “the ice is very thin.” Officials have said that in two weeks, when they will start to be able to see if infections are picking up again, they may have to shut everything down once again.

My assumption – and it may be naïve, but it seems reasonable to me – is that these countries that have had relatively severe lockdowns are likely to see less of a “second wave” when they emerge from lockdown. That’s because they have a smaller base of active virus carriers. So they may have had a more severe downturn, but they’re likely to see a steadier upturn, too. We shall have to see, though.

Why is the US opening up now?

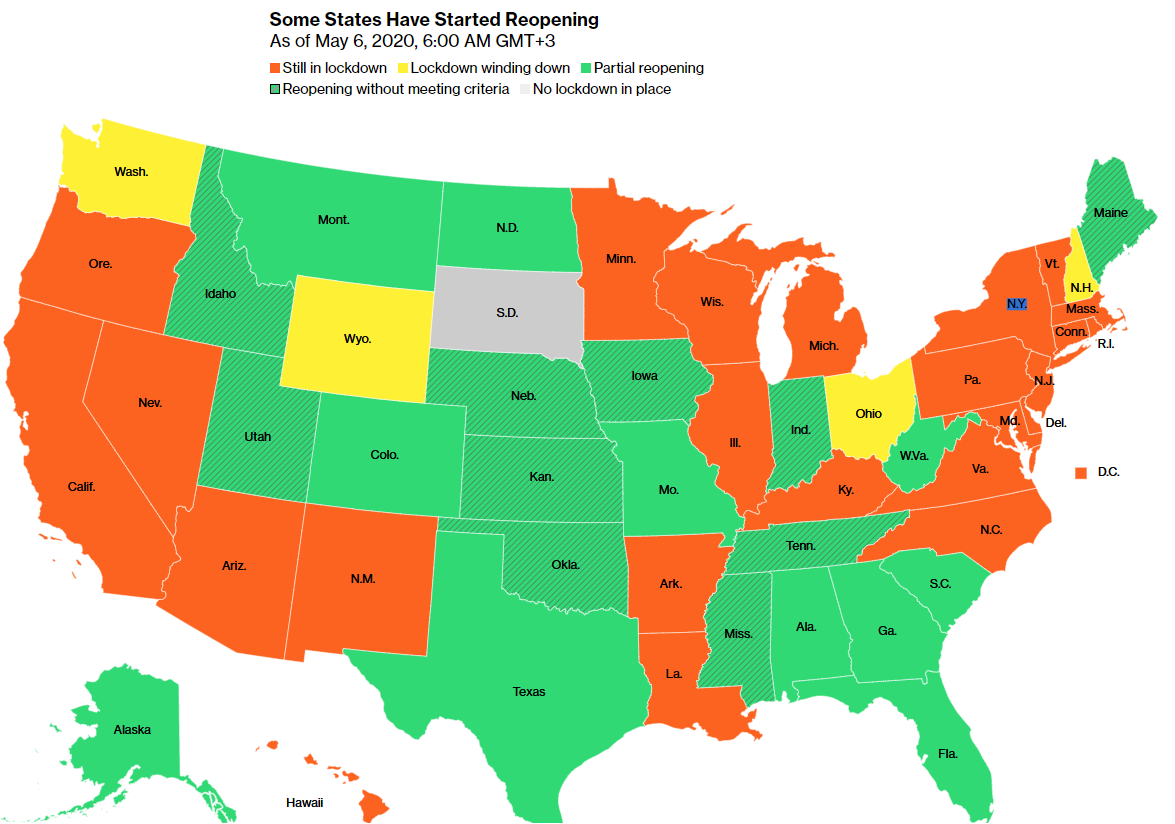

In the US, 30 of the 50 states have started or will soon start to reopen. However, unlike in Europe, most of these states haven’t gotten the virus under control. (Map from Bloomberg)

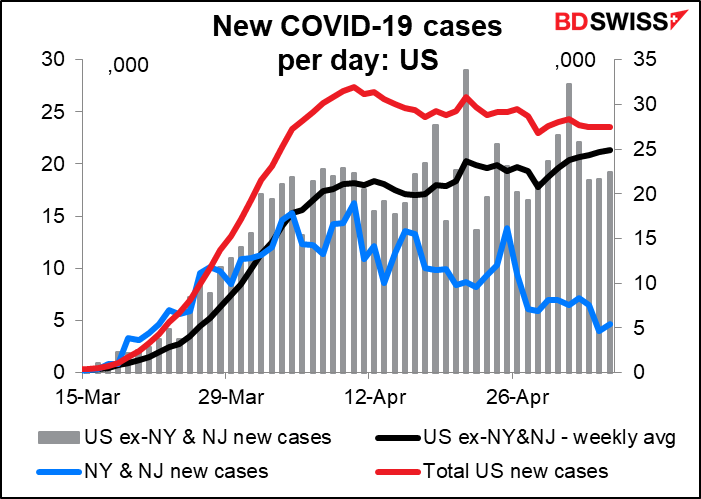

The overall new case count in the US is falling, which has allowed Trump & Co. to declare some measure of victory, but it’s all due to the severe lockdown in the New York area. If we eliminate New York and its neighboring state, New Jersey, the number of new cases in the US is still rising. In more than half of states easing restrictions, case counts are trending upward and/or positive test results are rising.

You may wonder why Trump and his henchmen are so eager to lift the lockdown when it’s obvious to anyone that it will just mean more people dying. The fact is, the lockdown was never meant to prevent people from dying in the first place. It was just meant to prevent too many people from all dying at the same time. That’s what’s meant by “flatten the curve” – reduce the peak number of people dying early on so that the health system can cope with it. The curve may be flatter, but it’s likely to be longer and therefore the area under the curve – the number of people who die – is likely to be the same.

The virus will still be around in the fall and winter and will probably get bad again at some point – the dreaded “second wave.” However, it’s better for Trump if this “second wave” comes earlier, during the summer, so that most people will either (one hopes) be immune or (alas) be dead by the time the fall & winter roll around. Trump wants to avoid overflowing hospitals in the fall and having to shut down the economy again right before the election. This is why Trump is pushing governors to lift the lockdown and reopen their economies now – he wants to get the illness and death finished with over the summer so that it doesn’t all hit right before the election.

In other words, the US doesn’t have a health strategy, it has an election strategy.

In an indication of this view, Trump has started to refer to himself as a “wartime president” and US citizens as “warriors.” And we all know what happens to a lot of warriors during a war.

(By the way, for those wanting to track the progress of the virus across borders, I recommend the FT’s Coronavirus Tracked page. It has an interactive graph that you cn use to track cases and deaths, both on an absolute basis and relative to population.)

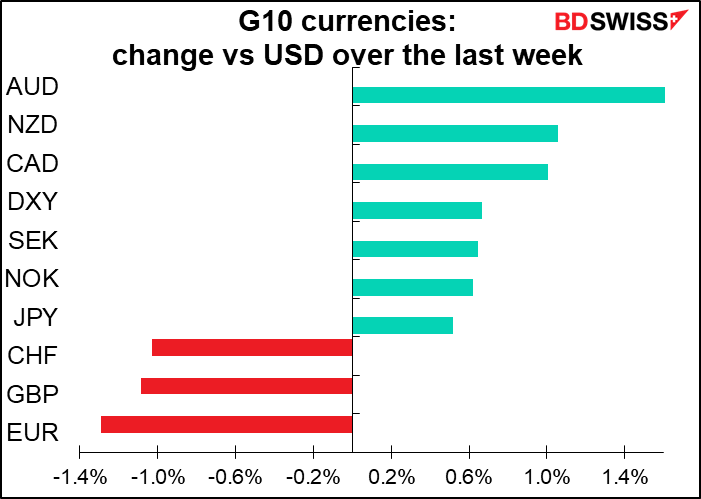

My expectation has been that while Europe was gradually emerging from lockdown and slowly but safely reviving economic activity, the US would be seeing the “second wave” of infections with more and more deaths. I thought – and still think – this would be a big negative for the dollar.

ECB’s troubles complicate EUR/USD picture

However, we now have the added complication of the German Constitutional Court ruling about the Bundesbank’s participation in the European Central Bank (ECB) asset buying program. So while the Fed is freely doing “whatever it takes” to keep the US economy afloat, the European Commission is struggling to find a way to fund its recovery program and the ECB is struggling to establish the legality of its activities.

On the one hand, the fiscal picture may become a bit clearer later today when the Eurogroup of Eurozone finance ministers holds an extraordinary meeting to come up with a compromise proposal about how to share the financial burden of fighting the pandemic.

But on the monetary side, the ECB issue seems quite problematic. It appears that the ECB will refuse to recognize the German court’s jurisdiction, which sets up a potential constitutional crisis in the Eurozone. Speaking in a Bloomberg webinar, ECB President Lagarde said, “We are an independent institution, answerable to the European Parliament, and driven by our mandate. We will continue to do whatever is needed, whatever is necessary, to deliver on that mandate. Undeterred.” The key phrase is that she believes the ECB is “answerable to the European Parliament,” not to the national courts. The ECB Governing Council is rightly concerned that if the German constitutional court can challenge its decisions, so too can France, Spain, Italy and Slovakia, as well as all the others. It will therefore refuse to answer.

That may be so, but what about the Bundesbank? According to the FT, ECB Council members are suggesting that the Bundesbank should answer in place of the ECB. However, the German court specifically asked the ECB to answer, not the Bundesbank. It therefore sets up a potential constitutional crisis that has the potential to delay and distract officials from acting quickly in this emergency. If worst comes to worst, the ECB may carry on undeterred, but the Bundesbank will have to stop participating. In effect Germany may have to withdraw from the Eurosystem. Ultimately I would assume German Chancellor Merkel will have to intervene in some way.

Even if this does get resolved, the fact that the Eurozone fiscal and monetary authorities have to jump through all these hoops to do what other countries have done quickly and efficiently just calls attention to the difficulty of managing the single currency during crises.

The situation for Europe is much more difficult than it was in 2008/09. In September 2008, the ECB’s refi rate – the-then policy rate – stood at 4.25%. There was plenty of room for the ECB to act unilaterally within its mandate to support the Eurozone economy by cutting rates. Now with its deposit rate at -0.50%, the interest rate tool is effectively exhausted. The Eurozone has to depend on fiscal policy instead. But EU-wide fiscal policy is the third rail of EU politics. If the EU governments can’t agree how to raise the money and the court won’t allow the ECB to support the bond market, then they are really…well, in polite company we economists would say that it calls into question the entire policy framework for the eurozone. The problem with monetary union has always been the absence of some way to make fiscal transfers from surplus to deficit countries. The ECB has been fulfilling that role by stealth.

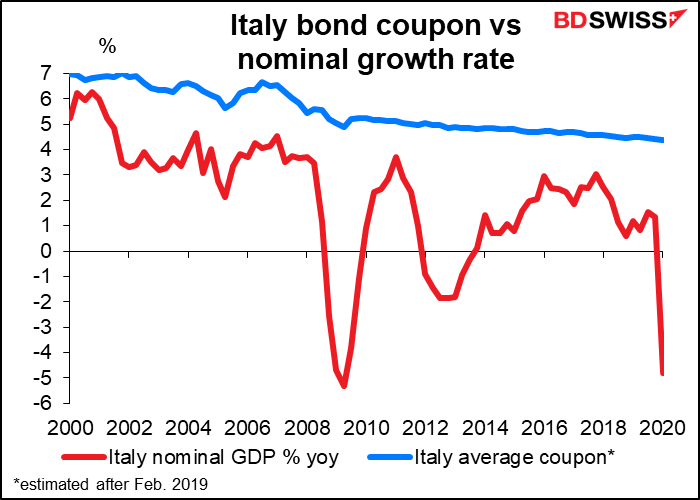

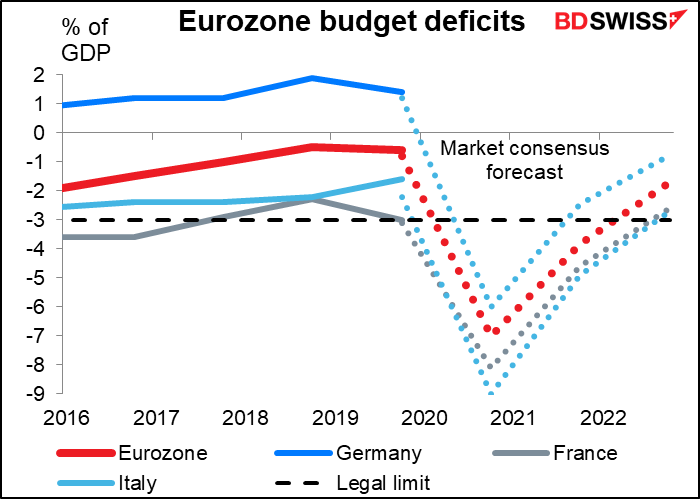

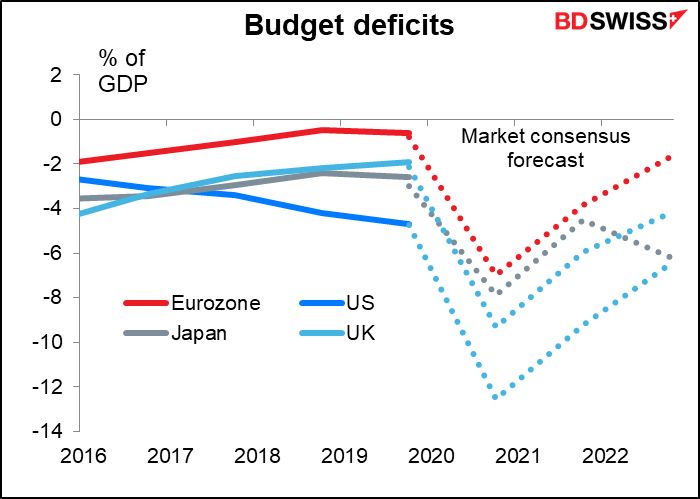

This role is going to be even more necessary this year, when Italy will have an enormous budget deficit of 9% of GDP, according to the market consensus. Without the ECB buying Italian bonds and “closing the spread,” as ECB President Lagarde said, how will they manage to raise that much money? Even now the cost of its debt is so far above the country’s nominal growth rate that a debt spiral seems inevitable without ECB help. (A debt spiral occurs when the cost of servicing the debt grows faster than the government’s revenues, causing the accumulated debt to snowball until the country has no option but to default. This happens when the amount the government has to pay is higher than the country’s growth rate.)

Indeed, with all the Eurozone countries expected to run huge deficits this year and next – even Germany – it’s hard to see how they can get through this without the ECB acting as “buyer of first resort.”

At the end of the day, I expect that as usual all parties will find some way to “muddle through,” which is SOP in Europe. It’s just likely to make monetary policy more cumbersome and therefore less efficient – almost as inefficient as fiscal policy. And the uncertainty is likely to drag on the euro.

So there we have it: worries over health policies in the US, worries over fiscal & monetary policies in Europe. EUR/USD is likely to be caught between these two forces for some time. For now, I think the US has the upper hand, because the European problems are more immediate. The result is likely to be downward pressure on EUR/USD. But gradually I think Europe will find some solution to its policy problems at the same time as the US’ death rate climbs to unacceptable levels. Then the currency pair is likely to reverse.

Next week’s indicators: US CPI & retail sales; UK short-term indicator day; China IP & retail sales; RBNZ meeting

The coming week has several indicators that, under normal circumstances, would be quite important for the markets. As I’ve pointed out before though, with most central banks on hold for the time being, the only significant statistic is the virus count.

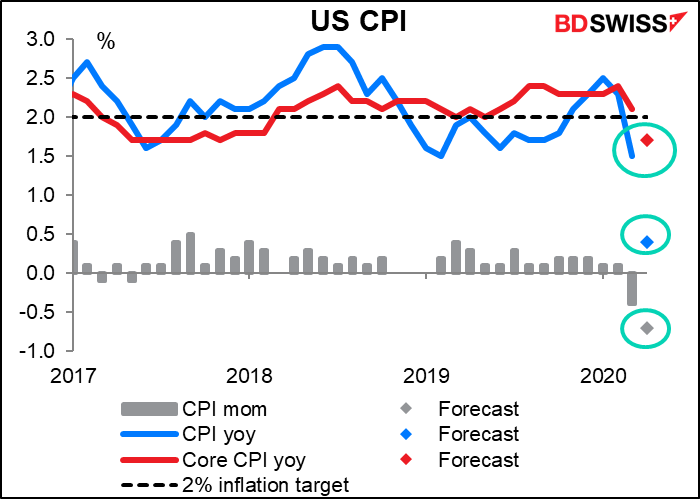

US consumer price index (CPI) would normally be the highlight of the week, but since the US is already doing virtually everything it can, there’s not likely to be any reaction from policy-makers even if inflation does slow further. Still, a 0.7% mom fall in headline prices, resulting in the headline rate of inflation plunging to only +0.4% yoy, is bound to raise some eyebrows. It wouldn’t be a record mom decline – that honor goes to -1.8% mom in Nov 2008 – but it’s close. It’s only been exceeded one other time, -0.9% in July 1949 (data back to 1947). (Oil fell from a peak of around $145/bbl in July 2008 to $50/bbl in November 2008.) Core inflation, which excludes energy costs, isn’t expected to show such a dramatic fall, but it’s expected to drop below the Fed’s target rate of 2% yoy.

In the context of the Fed’s “dual mandate” to promote “maximum employment and stable prices,” the incredible jobless claims alone are adequate justification for the Fed’s extraordinary policies. Nonetheless, CPI data showing the country teetering on deflation will add additional justification to the Fed’s extraordinary policies.

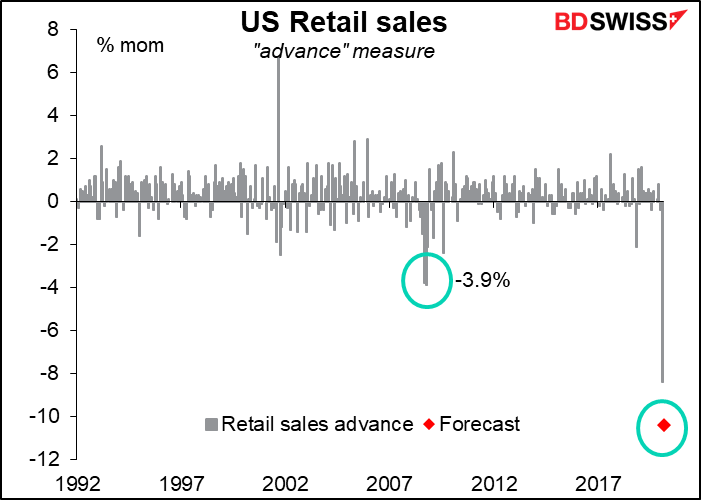

Last month’s record 8.7% mom decline in US retail sales was bad, but this month’s forecast 10.4% plunge is expected to beat it. The previous record, -3.9% mom, looks modest by comparison.

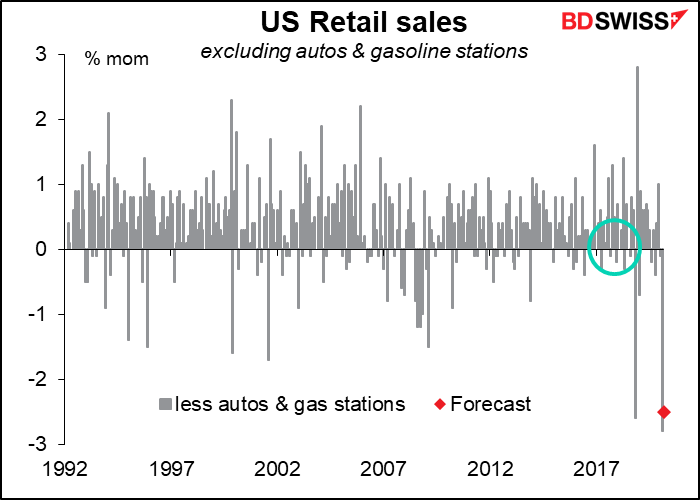

A lot of that is just a drop in sales of autos (which account for some 25% of retail sales) and falling gasoline prices. Taking those out, we still get a near-record fall, but a much more modest one: -2.5% mom, vs the record -2.8% in March.

Other important indicators coming out from the US during the week include the US government’s monthly budget statement for April on Tuesday. I don’t usually look at this, but with the US expected to issue a record $3tn in bonds this year, perhaps talk of the “twin deficits” will once again become a market factor. Although every government is expected to blow up its budget deficit this year, the US case is particularly worrisome.

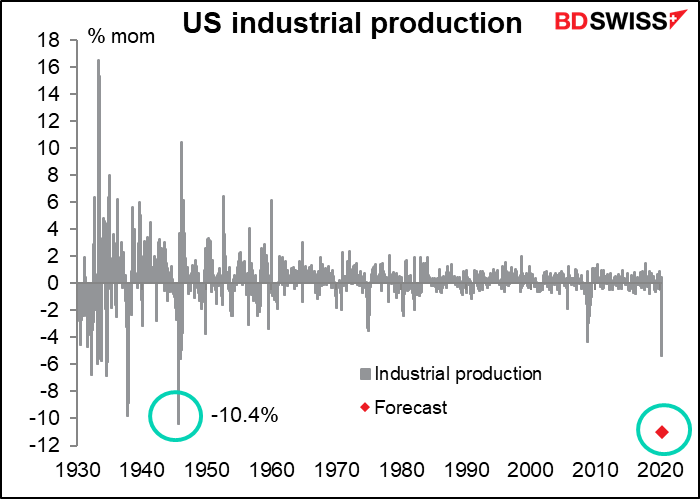

Finally, there are a number of significant US indicators out on Friday. Industrial production for April is expected to show a record drop of 11% mom, beating the previous record of -10.4% in August 1945. What a contrast though — the plunge in US industrial output back then must have signified a better future for everyone, rather than the dismal prospect that it implies today.

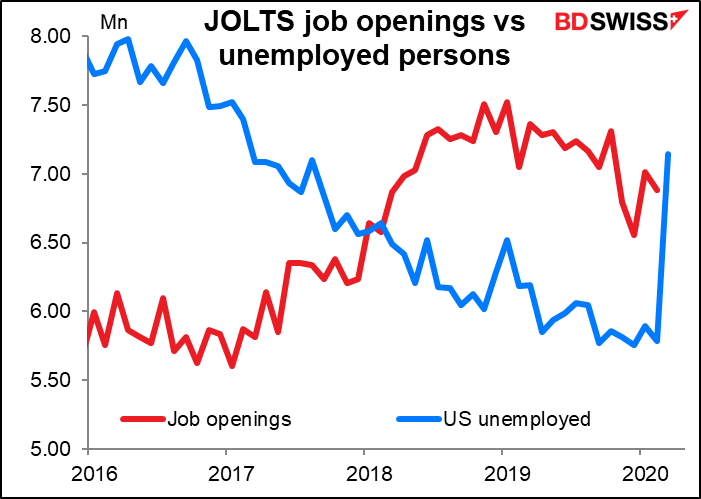

We also get the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report, which gives us a figure for how many open positions there are in the US. For around two years there have been more openings than unemployed persons, but that exceptional situation came to a screeching halt in March. Knowing how many job openings there are will help to gauge how quickly the labor market will recover once activity starts to come back.

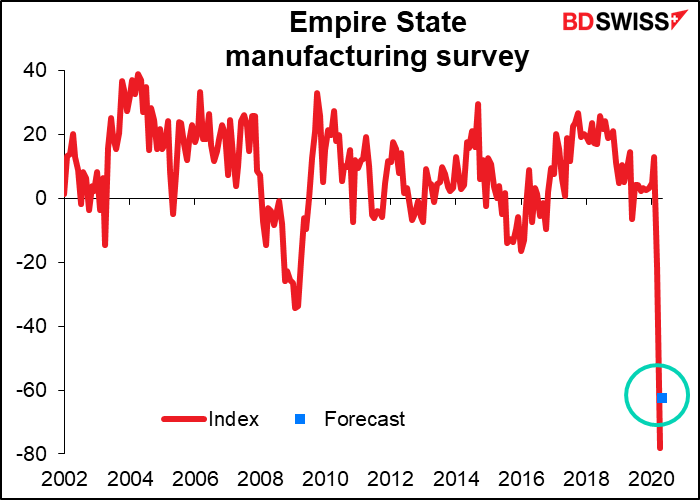

The Empire State manufacturing index is expected to rebound slightly. In fact, none of the six economists guessing forecasting the index expect it to be below April’s level. I suppose it’s because the index measures the percent of respondents who say things are getting better minus the percent who think things are getting worse, and if a lot of people only think things were just as bad as they were in the previous month, then the index will go up. That doesn’t mean conditions are improving though – it only means that they’re not necessarily getting worse. When your business is totally shut down, it’s hard to get worse than that.

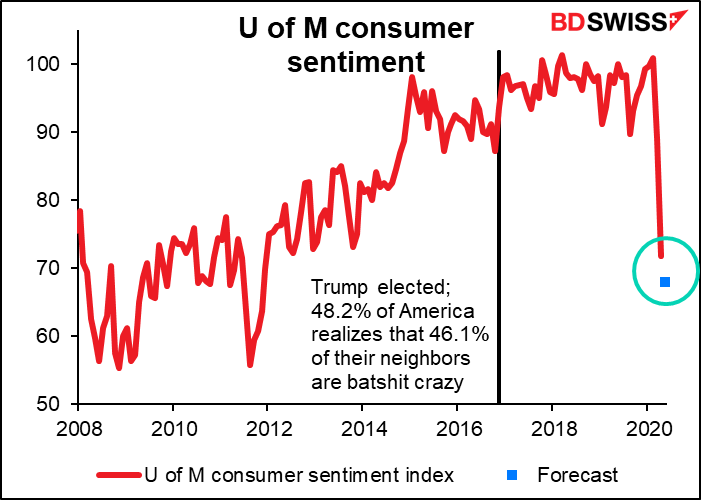

Finally, the U of M consumer confidence index is expected to fall, but not to the levels seen in the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/09.

And of course the weekly jobless claims will be closely watched, as usual nowadays.

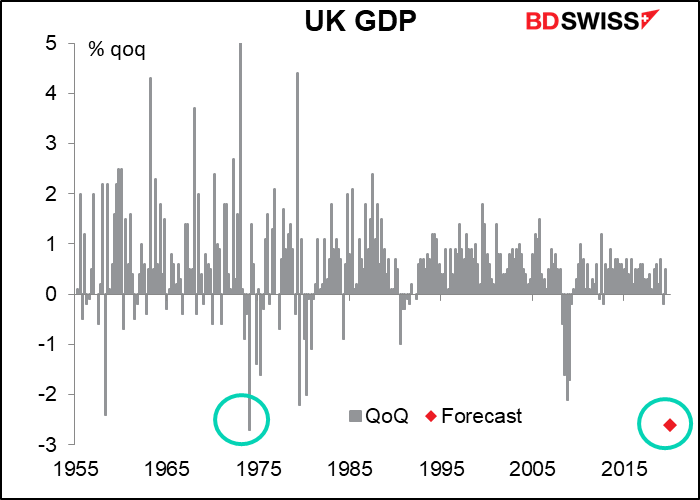

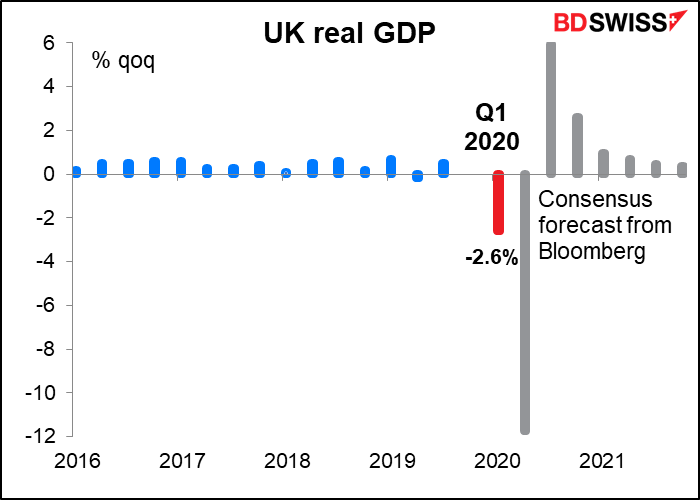

Wednesday is short-term indicator day for the UK, when the GDP, industrial production, and trade figures for March will be released.

The most important of these is the GDP figure, which in this case is for Q1 as a whole. It’s expected to show a near-record decline of -2.6% mom, second only to the -2.7% qoq fall in Q1 1974. That was when the oil shock combined with a miners’ strike and forced the UK economy onto a three-day work week to conserve energy.

Q2 is expected to be even worse – much, much worse (-11.8% qoq), but the market looks for a sharp (+6.0% qoq) rebound in Q3 and steady growth after that.

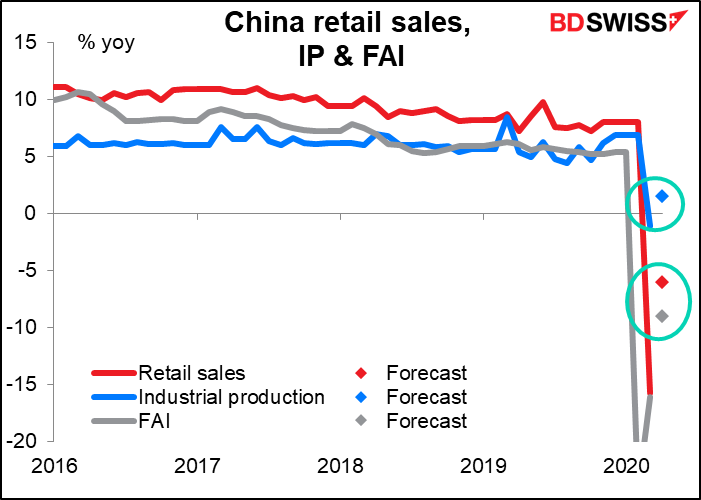

China releases its CPI and producer price index (PPI) on Tuesday and then its trio of retail sales, industrial production and fixed asset investment on Friday. They’re expected to show growth still well below normal, but better than in March. Chinese data is important for the world to get a glimpse of how quickly an economy can recover after undergoing severe lockdown. The answer seems to be more of the proverbial “Nike swoosh” gradual recovery than the much-anticipated “V”-shaped recovery people were hoping for.

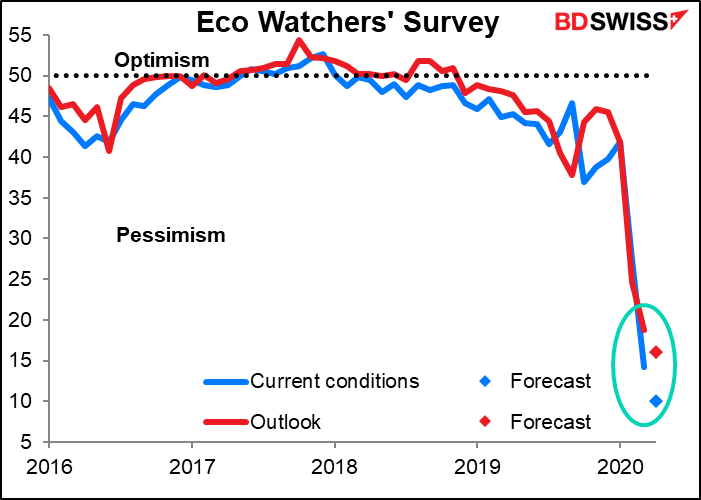

Wednesday we get the April Japan’s Eco Watcher’s survey of grass-roots workers who work in client-facing service-sector positions, such as taxi drivers, restaurant owners and pachinko-parlor operators. This seems to be a better indicator of service-sector conditions than the service-sector PMI. It’s expected to worsen yet again, but at least the “outlook” remains higher than “current conditions.”

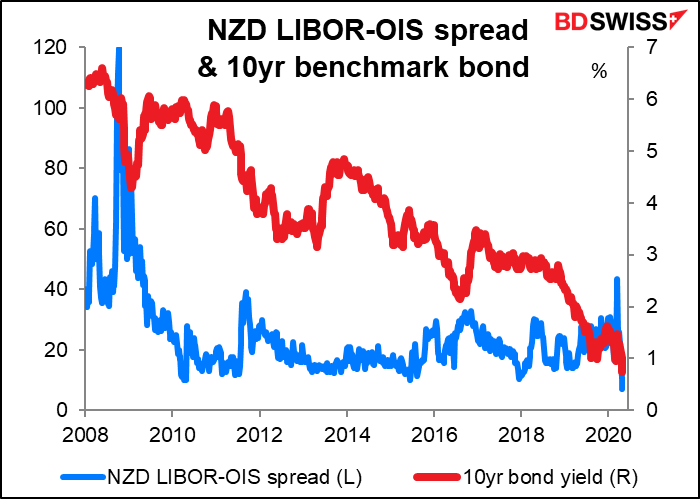

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) is the only major central bank meeting during the week. The RBNZ had two meetings in March: a scheduled one on 16 March, at which they cut the Official Cash Rate by an unusually sharp 75 bps to 0.25% and pledged to keep it there “for at least the next 12 months,” and an emergency meeting on 23 March at which they decided to begin a Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) program in which they will buy up to NZD 30bn of government bonds over the next 12 months. That would be almost half of the existing market, which totals NZD 65.5bn. They also removed some restrictions on mortgages and introduced several new ways to supply funds to banks.

The RBNZ can claim considerable success with all these measures. The NZD LIBOR-OIS spread, a measure of the difficulty that banks have funding themselves, hit 45 bps in March, but was down to what appears to be a record low of 5 bps this week. The benchmark 10-year bond yield also hit a record low of 0.73%. In fact, some market participants are starting to question whether the RBNZ’s actions might be distorting the market too much. Meanwhile, the country recorded no new cases of COVID-19 for the first time since early March – not due to RBNZ policy of course but a fact that should add to their confidence in the future as it means the government can continue to ease lockdown restrictions.

I expect that the meeting will be much in the same mold as the recent Reserve Bank of Australia or the Bank of England meetings: no change in policy and reiterating that things are getting better but they stand ready to do more if necessary. The interesting part, like at those meetings, will be the updated forecasts in the quarterly Monetary Policy Statement that will accompany the meeting.