The yen is well known as a “safe haven” currency: that is, one that appreciates when there’s some major trouble in the world. This phenomenon is well documented but not that well understood. For example, the graph below shows how USD/JPY tends to fall (i.e., the yen tends to strengthen) when risk aversion rises, as measured by the Westpac risk aversion index.

Many people wonder just why the currency of the most indebted G10 country, one with a high reliance on exports for growth — a currency that’s been described as “a bug in search of a windshield” — should be a “safe haven” when things get bad. It’s particularly bizarre when the trouble facing the world is something like a North Korean missile test, which is right in Japan’s backyard.

The reason for this behavior has little to do with the safety of the Japanese economy, much less the islands themselves. According to a paper by the IMF (“The Curious Case of the Yen as a Safe Haven Currency : A Forensic Analysis”) it basically comes down to the hedging behavior of Japanese investors when either they get nervous about the world outside their country or they start losing money in the Tokyo stock market.

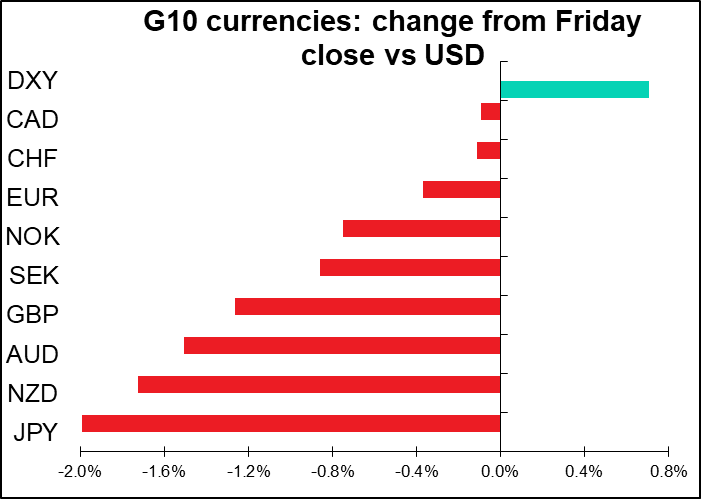

But what’s noticeable now is how the yen has not been exhibiting this behavior for the last day or so. That’s significant. For you Sherlock Holmes fans, the fact that this dog isn’t barking suggests where the yen may be headed.

The following graphs shows USD/JPY (black line) and USD/CNH (red line, inverted). The first graph is from 10 Jan to 3 Feb, the second from 3 Feb to 17 Feb. Note how closely correlated they: a rise in USD/CNH – bad news for China — was generally accompanied by a fall in USD/JPY (risk-off behavior among Japanese investors). Moreso in the first graph, but still generally in the second graph as well.

But now? The following graph shows the two from 18 February (Tuesday). It seems to me that this relationship has totally broken down.

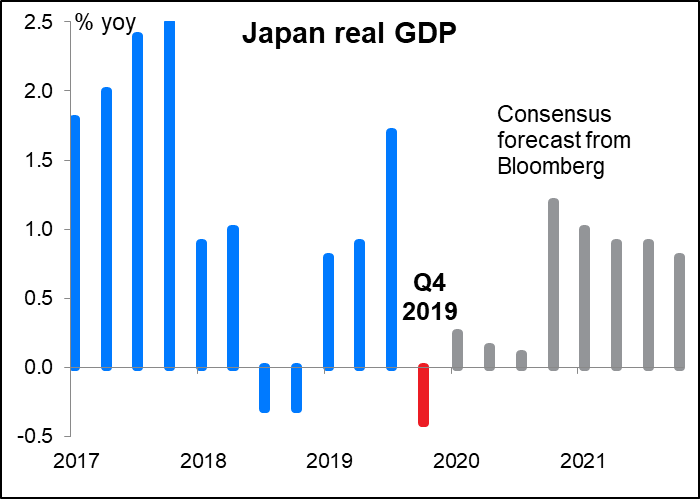

What might be causing this? I think the market has realized that problems in China are particularly bad for Japan. The worse-than-expected Q4 GDP figures, which came out right before the start of 17 February on these graphs (which are done in GMT) may have been the trigger, even if it took a day or two to hit home.

The January trade figures were better than expected – exports especially – but machinery orders plunged in December and are likely to be even worse in coming months, as one-quarter of orders come from abroad.

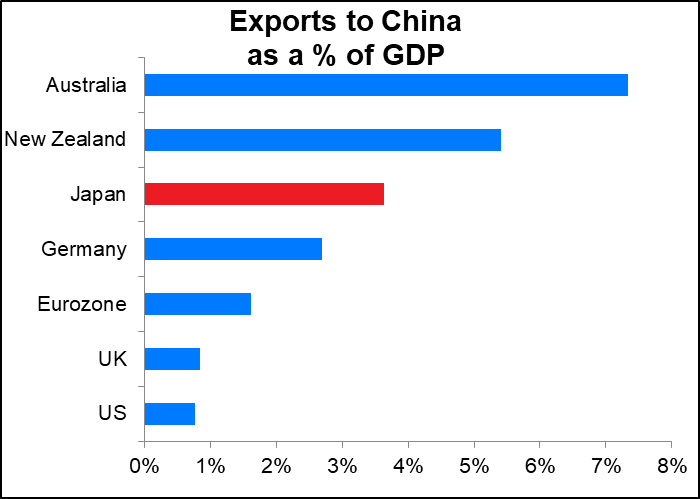

Japan’s exposure to China is indisputable: exports to China as a percent of GDP are significantly higher that Germany or the US and nearly on par with New Zealand (although nowhere near Australia).

As the virus affects Japan’s economy more and more, it’s going to show up in the indicators, which have been missing expectations recently. Indicators are likely to miss expectations more and more, until the market has revised down its expectations for Japan sufficiently. This is of course different from the US, where indicators have been beating expectations recently.

The difference between the surprises to the market’s expectations for US and Japanese indicators is a fairly good indicator of where USD/JPY is headed. Right not, it says the pair is likely to be headed higher.

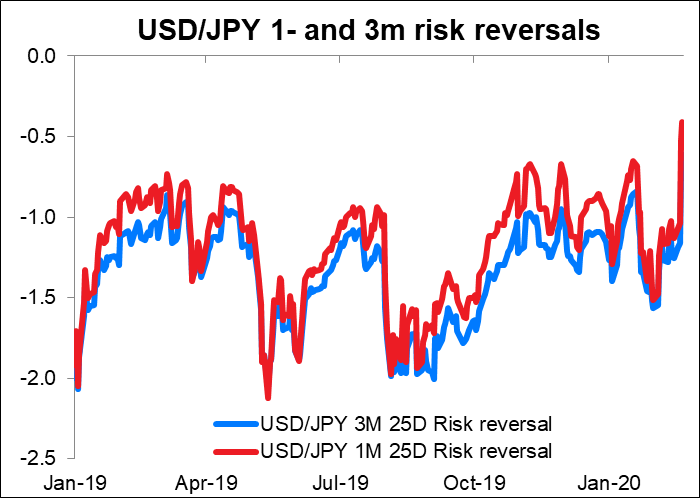

One sign of the turnaround in sentiment to JPY: USD/JPY risk reversals, which have been showing a premium puts over calls (i.e., positioning for a decline in USD/JPY or a strengthening of the yen), suddenly went shooting up.

As far as we know, speculators are already short JPY, but only modestly so. Positioning should be no obstacle to further declines.

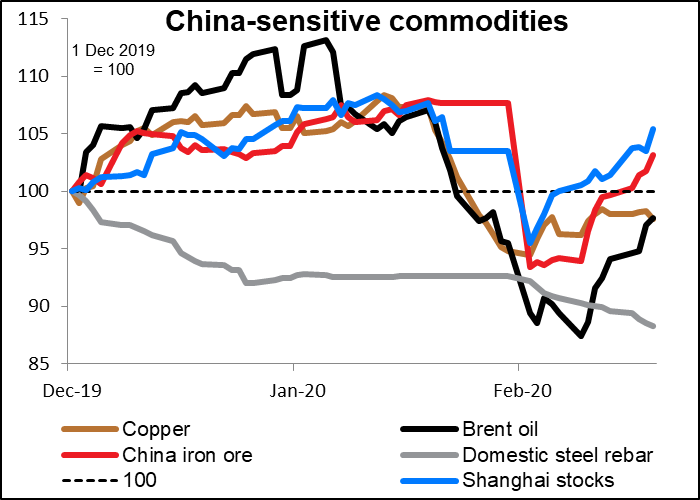

Of course, it is possible that I’m totally wrong. Maybe I have it backwards. It could be that the market is simply discounting the end of the COVID-19 virus entirely and expecting a prolongued “risk on” period that will naturally lift USD/JPY. Indeed, looking at the Shanghai stock market or the China iron ore price, one could be forgiven for thinking that the virus was a thing of the past, while copper and oil are certainly saying it’s not likely to be as bad as people thought. Only domestic steel rebar, used in construction, seems to be indicating any major problems in Japan.

However, this is Japan – those wonderful people who brought you Fukushima. Have you been following the saga of the Diamond Princess cruise ship that just discharged 3,700 people – of whom at least 621 were known to be infected? The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said tactfully that Japan’s efforts “may not have been sufficient to prevent transmission among individuals on the ship.” For a less diplomatic discussion, watch this YouTube video by Prof. Kentaro Iwata, Professor of Infectious Diseases Therapeutics at Kobe University. Start from 4 minutes in, where he says, “It turns out that the cruise ship was completely inadequate in terms of infection control…It was completely chaotic.” “…There was no single infection control person inside the ship and there was nobody in charge of infection control as a professional…Only the bureaucrats were doing the job, completely layman’s work, violating all the infection control principles.” “I can’t bear it,” he said.

According to a recent study in the Journal of Travel Medicine (“Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China”), Tokyo is the third most popular destination for visitors from China. It received 1.086mn visitors between February and April last year (Taipei was #1 with 1.359mn and Bangkok was #2 with 1.232mn.) Visitors to the US were quite low by comparison: 473,497 to Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York combined, or less than half the number going to Tokyo alone. Japan meanwhile also had a good number of visitors to Nagoya, Osaka, Fukuoka, Okinawa and Sapporo as well as Tokyo.

While Japan is rated much higher than most other Asian countries in terms of its ability to deal with an epidemic, the experience of the Diamond Princess does not give me much confidence in the government’s ability to do so. I also remember the AIDS-tainted plasma scandal back in the 1980s that the Ministry of Health hid; the chaos during the Kobe earthquake of 1995; the disaster in Fukushima; and various other episodes that give me no reason to expect the Japanese government to handle this crisis any better than it’s handled others.

So which is it going to be? Is the COVID-19 virus going to spread further globally and domestically, wreaking havoc with Japan’s growth? Or is it a big scare that will be no more than a severe flu and quickly pass? The point is, for JPY it doesn’t seem to matter: either way points to a weaker yen. If the virus proves resilient and spreads further, Japan will be one of the countries most severely affected and the yen will be likely to weaken because of that. If on the other hand the virus turns out to be not so serious, then the market is likely to switch into a “risk on” mood that should also cause the yen to weaken. It seems to me that the yen is likely to weaken either way.

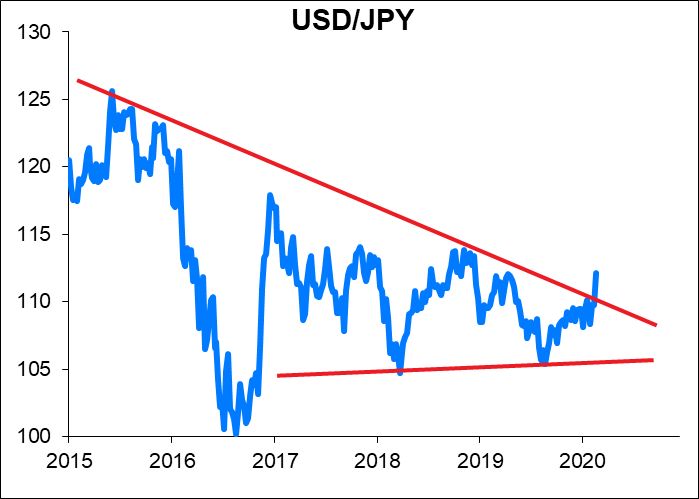

Technically, the pair has recently broken through the long-term resistance at 109.80. That too signals an upturn, in my view.

The coming week: Japan, US & EU inflation

The coming week is relatively quiet in terms of indicators. There are no major central bank meetings – only Israel and Hungary — and relatively few speakers on the schedule that we know of yet.

The main point of interest will be inflation numbers from Japan, the EU and the US on Friday.

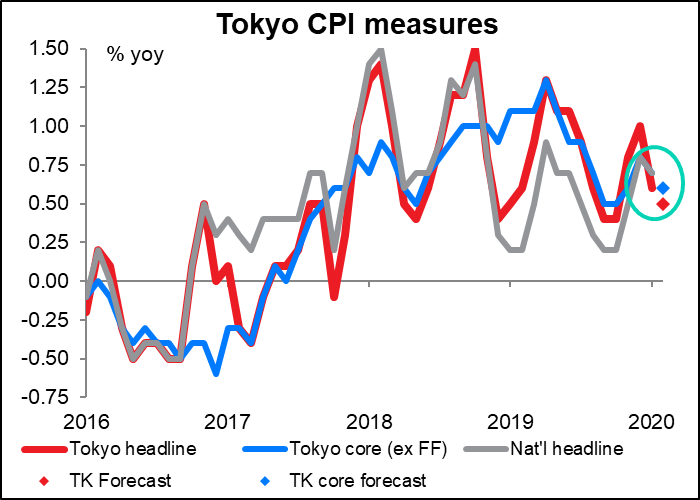

Japan releases the Tokyo consumer price index (CPI) for February Friday morning Tokyo time. The already-low inflation rate is forecast to drop one notch. The question is, how much further can inflation slow before the Bank of Japan (BoJ) admits that “momentum toward achieving the price stability target” has been lost? (as if it had ever been found in the first place.)

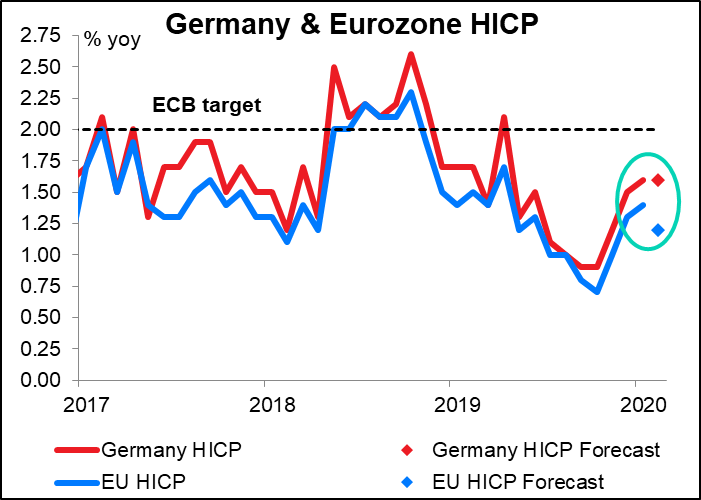

Germany and the EU announce their inflation numbers the same day, an unusual occurrence probably due to the short month. Normally the market looks to the German figure for a guide to what the EU-wide figure will be, but this month the German national figure will come out after the EU-wide figure is released. The German headline inflation rate is expected to be unchanged, but the EU-wide figure is forecast to decline, no doubt because of falling oil prices. (No consensus forecast for core inflation is available yet, which is a shame, because that’s what the ECB watches.) It’s debatable whether a slowdown in headline inflation would be negative for EUR though, because the ECB does tend to focus on core inflation. Nonetheless these are the last inflation figures that the Governing Council will get before its 23 March meeting. A slowdown in inflation, even at the headline level, could prompt some discussion about whether further measures were necessary. EUR negative

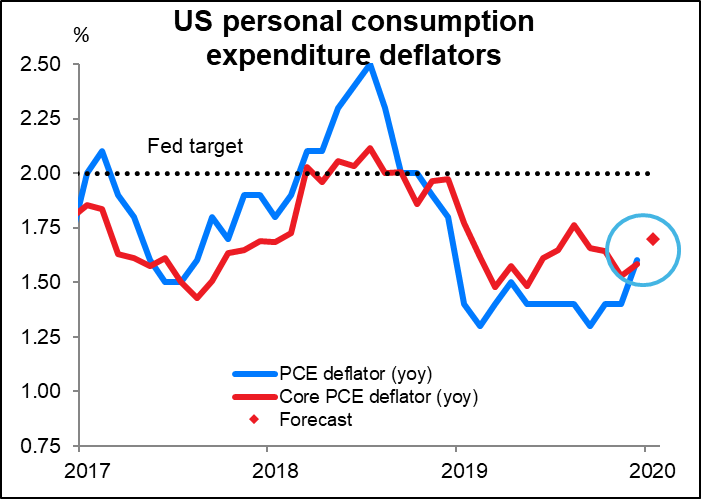

Later in the day, the US announces the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator and its sub-index, the core PCE deflator. This, and not the consumer price index, is the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. The FOMC stated back in January 2012 that the PCE deflator was “most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate.” They didn’t say specifically that they focus on the core PCE deflator, but it’s widely assumed, because of various hints they’ve dropped over the years. For example, in this month’s Monetary Policy Report to Congress, they said that the core PCE deflator “historically has been a better indicator of where inflation will be in the future than the overall figure.”

The core PCE deflator is forecast to accelerate somewhat, bringing it nearer to the Fed’s 2% inflation target. That’s pretty good, considering everything else that’s going on in the world. With the unemployment rate at a 50-year low and growth around what the Fed assumes is the potential growth rate for the country, it means a cut in interest rates is that much less likely. USD-positive (No consensus forecast for the headline figure available yet.)

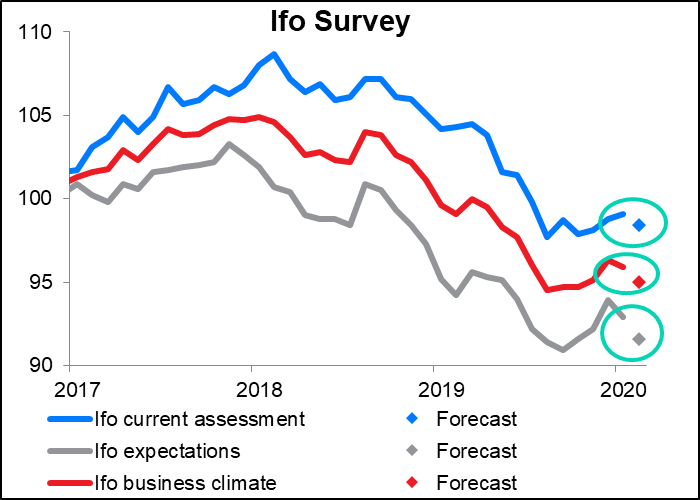

Other important indicators out during the week include Germany’s Ifo index on Monday. It should come as no surprise that all of the indices are expected to be lower. The only question is whether the actuals are going to be even lower than the forecasts. Notice that the expectations index (grey line) is forecast to fall by more than the current assessment (blue line). That’s really bad, considering that everyone has until recently been expecting the German economy to rebound. EUR negative

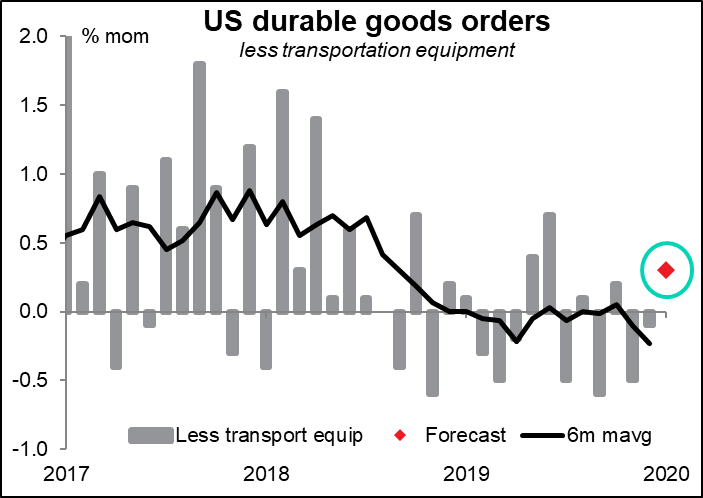

In the US, we get durable goods on Thursday as well as personal income & spending on Friday (along with the PCE deflators). The durable goods less transportation equipment figure is expected to be up modestly, but this isn’t much of a rebound considering how weak the figures have been recently – declines in four of the last six months. Even this figure wouldn’t be enough to turn the 6-month moving average positive. I think even though it’s an increase, a figure this weak would show a continued lack of investment in the US, which is negative for the dollar.

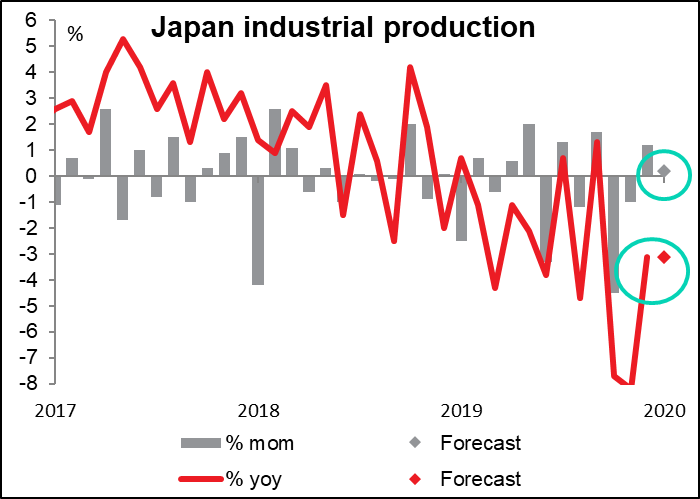

Japan has its usual end-of-month slew of indicators out Friday morning. Along with the Tokyo CPI, the country will announce the jobless rate, job-offers-to-applicants ratio, retail sales and industrial production. None of them is particularly important for the FX market nowadays, though. If any, I would look at industrial production to see how output was recovering from the post-consumption tax hike before the COVID-19 virus had a chance to bite.

There are no major UK indicators out during the week. Instead it’ll just be he said-he said on Brexit and more speculation about what giveaways the new Chancellor has in store for the Budget in March.