We’ve seen an unprecedented flurry of activity by central banks and governments around the world, too numerous to catalog. The best summary I’ve seen of measures is on Quartz, which says is updating their page as new measures occur.

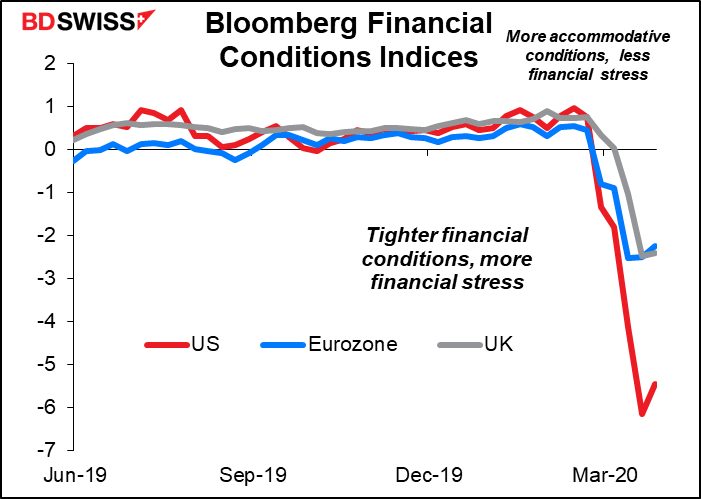

The results of these all-out efforts are starting to be seen in the markets. Indices of financial conditions have stopped worsening, although they have hardly started improving.

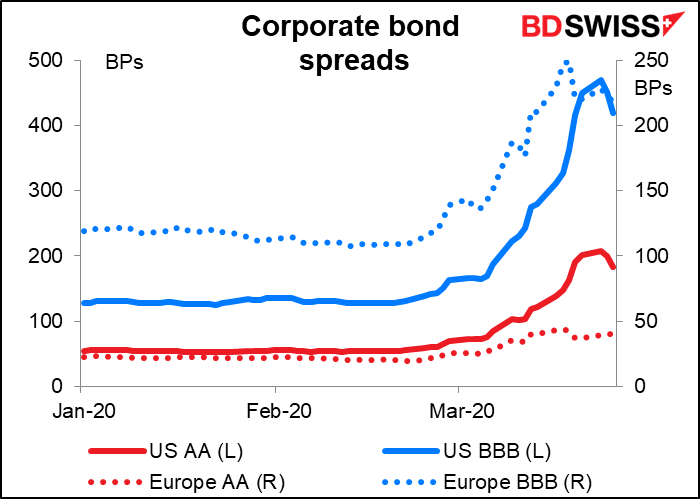

We can see that pattern in corporate bond spreads, which have stopped widening but hardly narrowed at all.

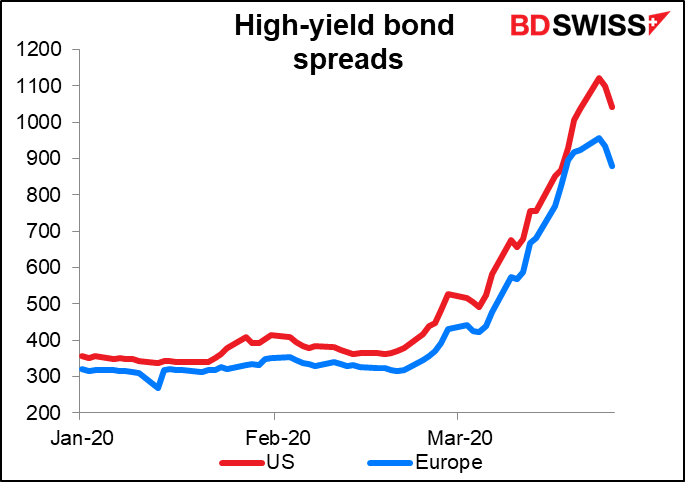

Including high-yield bonds, the riskiest.

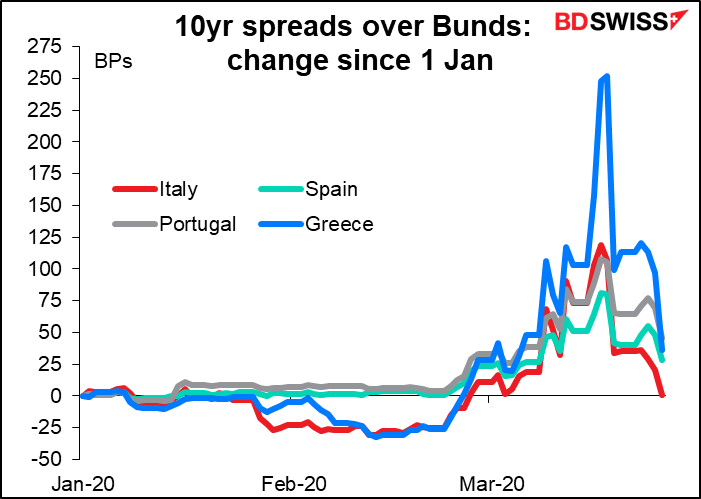

Official measures have had considerable success in narrowing spreads on Eurozone peripheral bonds. Italian spreads have even returned to where they were at the beginning of the year, thanks to the ECB’s new Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). In constructing the PEPP, the ECB abandoned its self-imposed limit on how much of any one country’s bonds it could buy. That change will allow it to target money to hard-hit countries like Italy, in line with ECB President Lagarde’s pledge that “there are no limits to our commitment to the euro.”

The LIBOR-OIS spread, which measures the difference between secured and unsecured lending, is still quite elevated, particularly in dollars. That’s a sign of nervousness about lending. However it’s nowhere near where it was during the 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis.

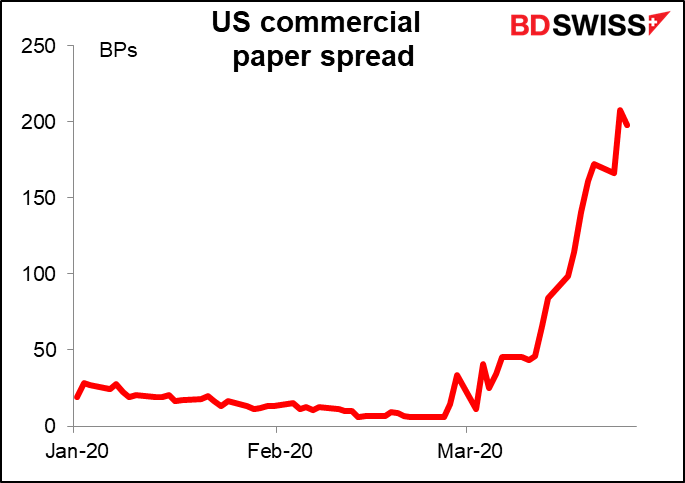

And US commercial paper spreads haven’t come in at all despite the Fed establishing the Commercial Paper Funding Facility.

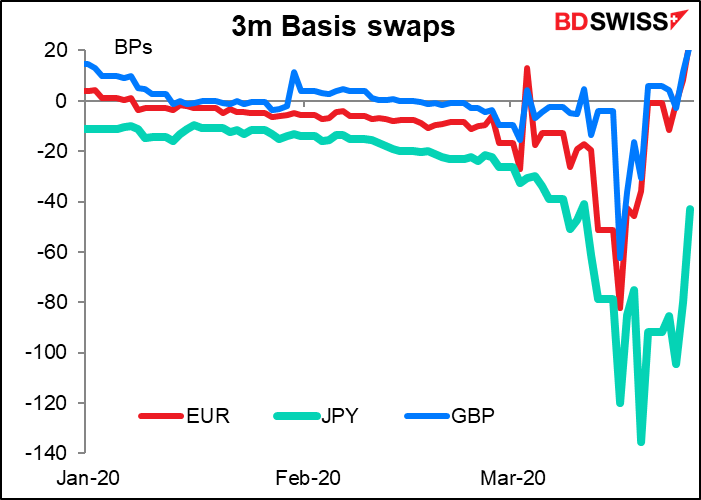

One area where central banks have had more success is in the supply of dollars. Through the Fed’s liberal supply of dollars through swap arrangements with foreign central banks, the currency basis swap has come in noticeably. This has taken a lot of the upward pressure off the dollar.

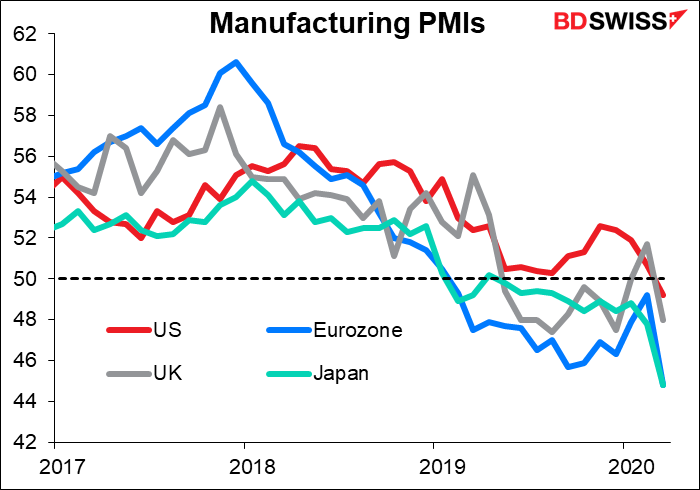

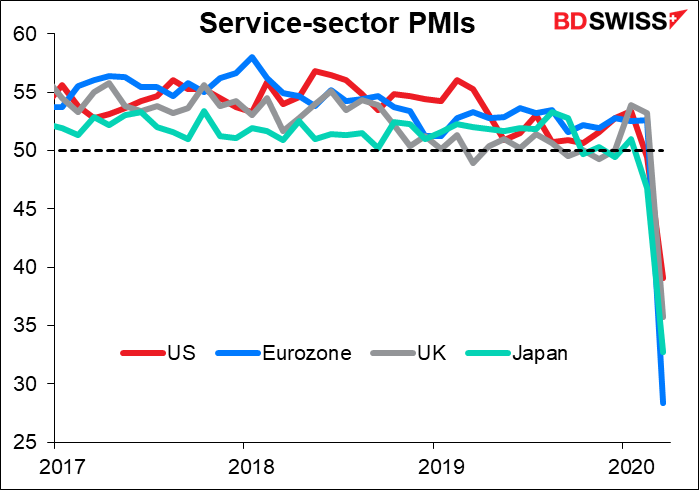

Meanwhile, the impact on the global economy is just starting to be felt. The preliminary Markit purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) fell to record lows in the major industrial economies. It’s particularly noticeable that the service sector is bearing the brunt of the slowdown, rather than manufacturing, as happened in 2008.

The impact on the service sector seems to have followed fairly closely the progress of the virus, as those countries that were affected earlier (or at least acknowledged that they were affected earlier) showed the steepest decline.

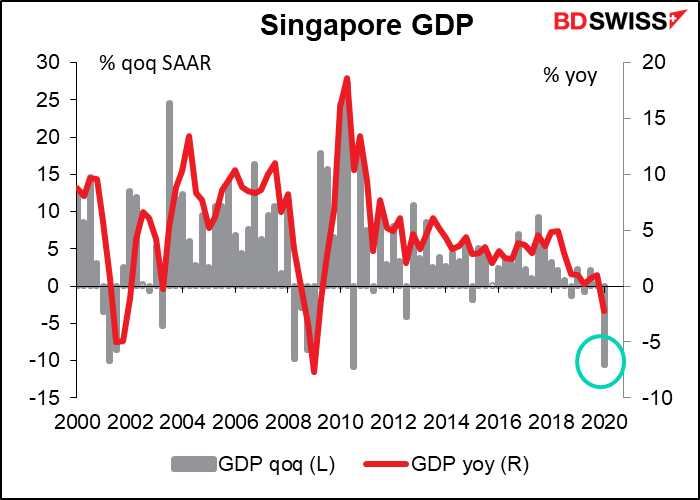

We can get an inkling of how the virus is likely to affect economies by looking at Singapore, which is the first country to announce Q1 GDP. It was down an astonishing.

What can we conclude from all of this?

- The role of policy-makers, particularly central bankers, is over for now. The fiscal and monetary authorities around the world have shown that they are willing to do whatever it takes to get their economy over this crisis. There will of course be some fine-tuning later. More money and different schemes may be necessary if the crisis drags on. But those are details; the will is clearly there. Some of the actions taken today may have implications for future monetary, fiscal and social policy, such as the German “no deficit” pledge or perhaps even EU-wide “coronabonds.” Similarly, the rescue package passed by the US Senate may reshape US social policy significantly.

- The torschlusspanik for dollars is over. The Fed’s swap arrangements with other central banks and those central banks’ stepped-up dollar auctions seem to have satisfied a lot of the urgent rush for dollars. We may now see the re-emergence of economic fundamentals as a driving force in the market.

I would argue that that bodes ill for the dollar, because the US is so far behind other countries in dealing with the virus problem. The lack of hospital beds and the utter, total and complete incompetence of the Trump regime, not to mention his deranged, demented comments and bald-faced lies at the press conferences about the virus make it more likely that the US will stumble into disaster. While other countries adopt a policy guided by science and health authorities, Trump is thinking only of the effect of this shut-down on his re-election chances. (In the famous words of EU politician Jean-Claude Juncker, “We all know what to do, we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it.”)

- The focus now moves to “how long will this last, and what will the recovery look like?

For the first question, I would refer to Dr. Anthonyi Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, who is shaping up to be the Hero of America as he struggles to keep in Trump’s good graces while correcting his lies, distortions and mistakes. Dr. Fauci said, “You don’t make the timeline, the virus does.”

There seems to be a different approach between Europe, which is moving towards indefinite total lock-down (here in Cyprus we can get arrested for being outside without permission), and the US, which not only is taking a much less severe policy but is also discussing lifting relatively soon the modest restrictions that it has in place. Trump has called for people to be back in church on Easter, which is Sunday, 12 April in the US. That’s not going to happen in Europe.

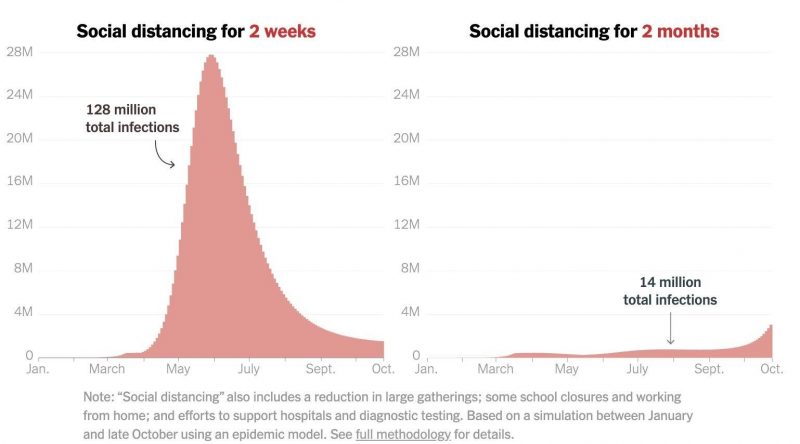

The New York Times did a study on the effect of social distancing and what would be the impact of a shorter or longer period. They argue that “quickly returning to normal could be a historic mistake that would lead to an explosion of infections, hospitalizations and deaths.” But it remains to be seen whether Trump will be convinced.

It also remains to be seen whether this analysis is correct. One study, by scientists at Oxford University, has called this reasoning into question. Other people have called this study into question. This is not my field of expertise so I won’t venture an opinion. However I will say that personally, I’m staying in my room.

Meanwhile, investors want to know what the shape of the recovery will be: will it be V-shaped rapid recovery, as it was after the SARS epidemic in 2002? A U, with a slower recovery? Or maybe an L: down but not back up for a long long time. (People were asking the same question about the Japanese economy in the early 2000s, except then we had the Japanese hiragana and katakana alphabets to choose from too, for a total of 98 additional letters.) So far it seems that the first leg is quite clear: down sharply. After that, it’s a question for epidemiologists, not economists.

Effect on currencies: mixed

As scientists settle upon the appropriate way of dealing with the virus, we may see currencies starting to differentiate depending on how well each government is enforcing the regulations and the prospects for recovery. In this respect, I think currencies may sort out on a FIFO basis: first in, first out. That is, those areas that first came to grips with the virus are likely to be the first to exit as well and should benefit accordingly. EG, China was obviously the first country hit, but is starting to emerge: as of 24 March, 71.7% of small- and medium-sized companies had resumed operations, vs 29.6% on 23 February, according to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

We can get an estimate of how well countries are abiding by the lockdown by looking at the Citymapper Mobility Index. Citymapper, a public transit app and mapping service, calculates how many people are using it to plan trips relative to a typical usage period. The data are remarkable; in Milan, traffic is only 3% of usual, Washington and New York were 6%-7%, in London it’s 12%, and in Tokyo it’s 21%. The highest was St. Petersburg at 69% (Moscow was 54%).

There is a confluence of factors affecting the currency markets. The most immediate has been The Great Dollar Shortage. Investors who borrowed some $12tn in USD effectively had a huge short position in the currency that had to be covered. That’s sent the dollar up higher.

As that position gets covered, I believe the relative success in each country in dealing with the virus will become more important. In that respect, the dollar is likely to be the #1 loser. Just think about it: China has 3x the population of the US, yet the US already has more COVID-19 victims than China. The US is likely to be overwhelmed in coming months while other, better-organized countries with better health care systems start to pull out. That’s likely to weigh on the dollar.

The counterpart to USD weakness is likely to be euro strength, as Europe’s stronger measures allow it to come out of the crisis earlier.

In that respect, GBP may be in for a period of extended weakness, as its response has also been patchy and its health service overwhelmed. Brexit is now the least of its problems.

There will probably be the usual “risk-on, risk-off” dynamic going on periodically. That means JPY and CHF are likely to surge occasionally as worries about the progress of the virus ebb and flow.

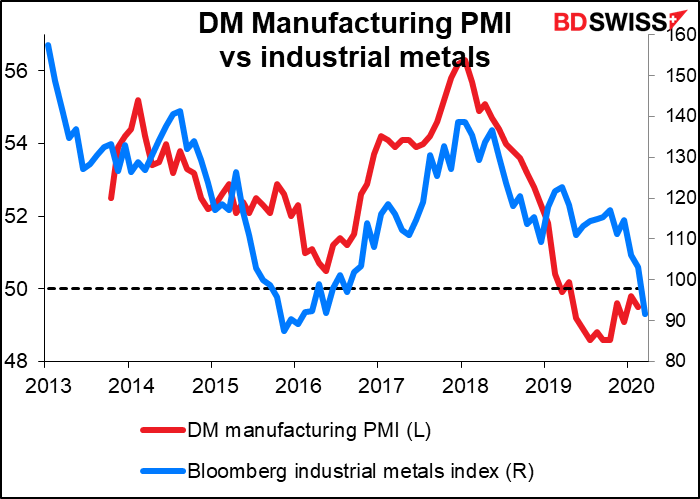

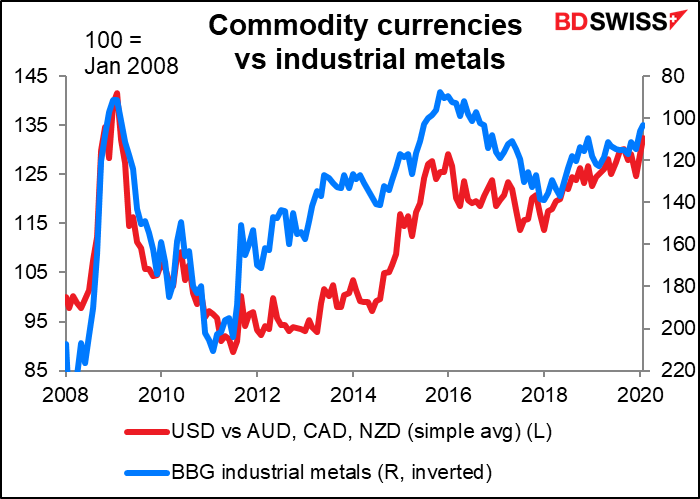

Finally, the commodity currencies are likely to do badly as commodity prices slump with the downturn.

This week’s indicators: the end of an era

The focus recently has been on the inflation data. The monthly US nonfarm payrolls (NFP) have been downgraded; last month, The Economist newspaper carried a story explaining why traders were losing interest in the jobs report.

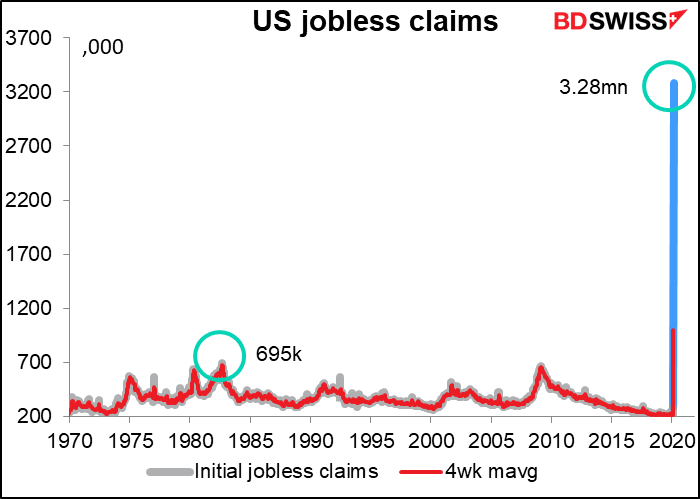

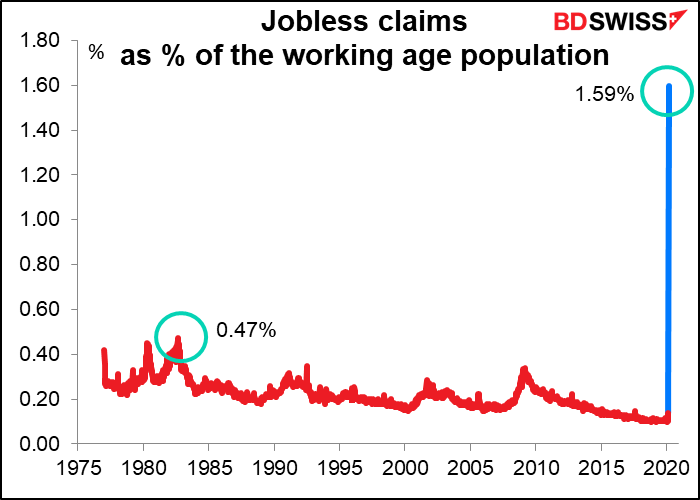

Sadly, those days are over. The record-breaking string of 113 consecutive months (9 years and four months) of increases in the final NFP figure is forecast to come to an end this month. After Thursday’s stunning initial jobless claims figure, which saw claims soar to an astonishing 3.3mn – almost 12x the previous week and 4.7x the previous record high (695k set in October 1982), the market is braced for a rapid turnaround in the employment situation.

The jobless claims figure represents 1.6% of the working population of the US thrown out of work in one week!

The reason is simple: most of the US private-sector workforce (82%) is involved in the service sector. The PMI figures above show that social isolation has devastated services as the bars and restaurants (which alone employ 7.5% of the US workforce) empty and everyone scurries home to watch Netflix. (Just FYI, visits to Pornhub are also up sharply, although I am not among those who would know about such things.)

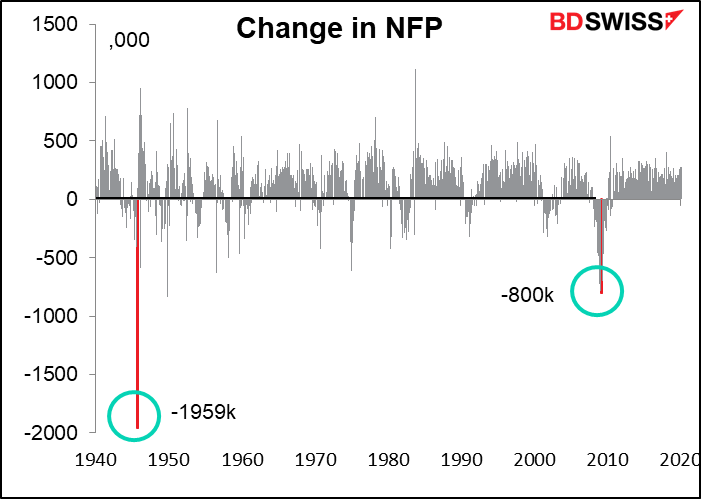

The NFP figure is expected to decline but not collapse this month. The figure is calculated from a survey that takes place during the pay period containing the 12th of the month. That week, claims were only 281k. This was a big jump from the previous week’s 211k (a 10 standard deviation change!) but nothing like the latest week. Nonetheless, payrolls are likely to decline in March not only because of people losing their job, but also because of a decline in hiring.

The real plunge is going to show up in April. Then, it’s certain the drop will exceed the 800k fall in March 2009 and probably the record 1.96mn fall in September 1945, which I assume was due to the end of wartime production in the US. (No, I wasn’t around then, so I don’t know for sure what caused it.)

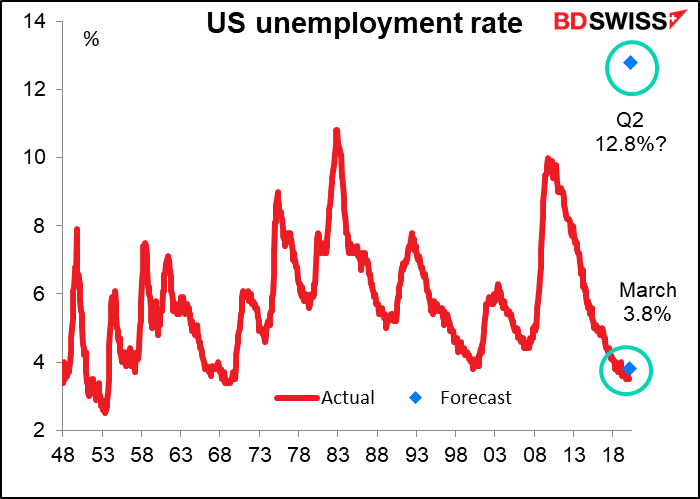

Of course, the population was much smaller then – 147.2mn in 1948 (the earliest figure I can find) vs 331mn today. So perhaps it’s better to talk in terms of the unemployment rate. The consensus forecast for the unemployment rate for March is 3.8%, not a major rise from 3.6% in February. However, that’s just the start. The investment bank Morgan Stanley for example is forecasting that it will reach 12.8% in Q2, which would be a post-war record.

All countries are in the same boat. The focus in the markets is therefore likely to turn away from inflation and towards the employment data to judge just how bad the downturn is likely to be. In the coming week we get employment data from Japan (Monday), Germany (Tuesday), and the EU (Wednesday), not to mention of course the US ADP employment report and the US Challenger job cuts on Wednesday too. (Canada, which usually announces its employment data at the same time as the US, does not this month.)

For Japan, the market is expecting no big change this month – the unemployment rate is forecast to remain at 2.4% while the job-offers-to-applicants ratio is expected to fall only slightly to a still-healthy 1.47.

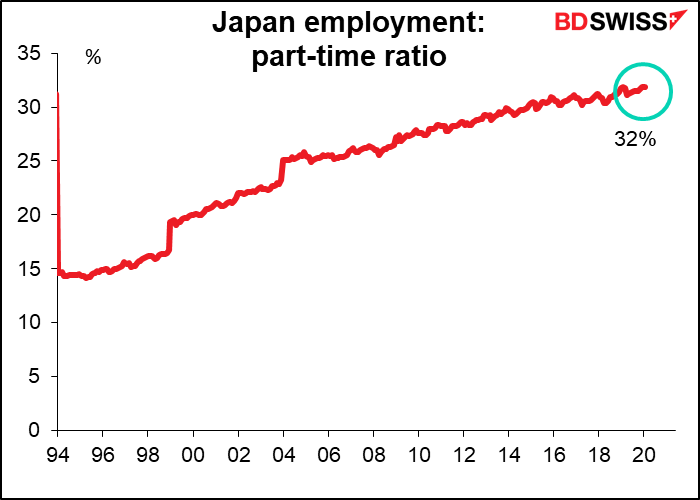

However, this can change rapidly. Although many people still think of Japan as the Land of Life-Time Employment, that social contract is fading fast, and in any case was limited mostly to men at large companies. An astonishing 32% of the workforce is comprised of part-timers who have no employment rights at all. They can be terminated at will, and most likely will be, too. I expect to see Japan’s unemployment rate swelling quickly.

Japan does have an “unemployment claims” data series, but it’s not particularly up-to-date (the latest data is from December) nor is it widely watched. I worked in Japan for 18 happy and fruitful years without ever hearing about it.

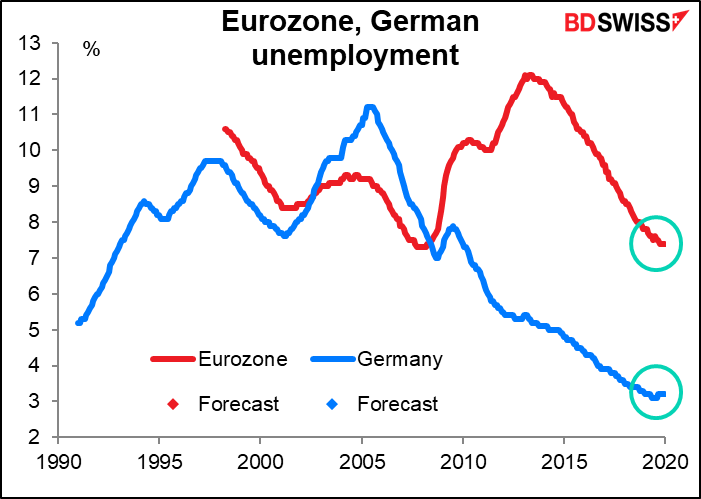

For Germany and the EU, strong social welfare measures to support employment are likely to blunt the impact of the crisis. In particular, Germany has its Kurzarbeitergeld compensation scheme that provides government support to companies so that they can keep workers on. The market expects no change in unemployment this month. I doubt if the EU can stand alone in this storm however.

There are some other indicators of interest coming out during the week. The final Markit PMIs for those that have released preliminary versions, plus PMIs for other countries (including China) will be released, together with the US Institute of Supply Management (ISM) versions (manufacturing on Wednesday, services on Friday). The Chinese official PMIs come out on Tuesday.

The German inflation figures will be out on Monday and EU-wide inflation on Tuesday, but no one is thinking about inflation nowadays.

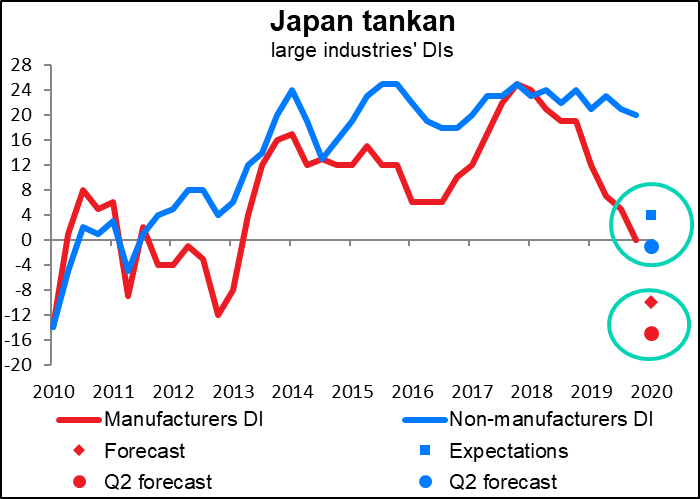

Finally, the Bank of Japan releases its short-term survey of economic conditions, universally known by its Japanese acronym the Tankan report. It’s expected to be pretty bad. The forecast 10-point drop in the large manufacturers’ diffusion index (DI) would be the largest fall since the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake, while the forecast 16-point decline in the large non-manufacturers would be the biggest drop since Q1 2009, the depths of the Global Financial Crisis. And the indices are expected to keep falling the next quarter, too.

Oddly enough, the non-manufacturers’ DI is expected to remain positive and even in Q2 is expected to go only to -1, whereas the manufacturers’ DI is expected to go deeply into negative territory this quarter. This contrasts with the experience of other countries (and also the Japanese PMIs), where the service sector has borne the brunt of the downturn. Apparently, information services and communication are booming in Japan, plus real estate and construction were helped by the mild winter.