One of the hottest debates raging among central bankers – insofar as central bankers rage, which admittedly is not very much – is over negative interest rates. There are different views among central bankers about what’s best once policy rates hit zero, known as the zero bound. If they want to loosen monetary policy even further, what’s best? Keep going and lower rates until they’re negative? Or other extraordinary measures, such as quantitative easing (QE), which brings down interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve? Or targeted lending programs? Or some other exotic measures?

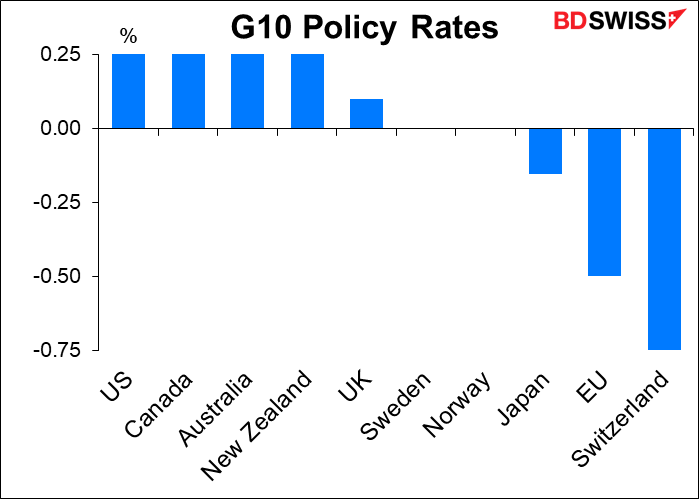

At the moment, it’s an argument over just a few basis points. After all, those G10 central banks that still have positive rates are only at 0.25% at most. It would only take a 26-bps move to send rates negative – hardly dramatic.

And yet, there seems to be something significant about negative rates. It’s seen as a much more significant step than the 26 bps (or less) would imply – a step through the looking glass into a different world. Never mind that they’ve been in use since 2012, when Denmark became the first central bank in the world to implement negative policy rates. Since then the European Central Bank (ECB), Hungary, Sweden’s Riksbank, the Swiss National Bank (SNB), and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) have all had negative rates at one point or another.

What are the views of the central banks that currently don’t have negative rates?

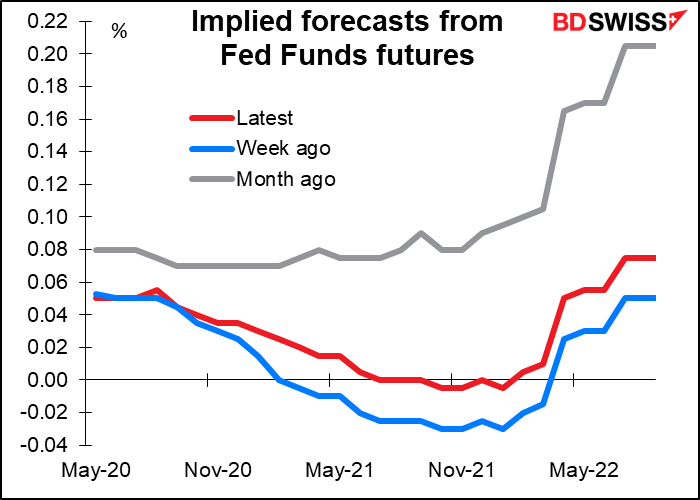

US: Not under consideration; unlikely Although the markets are now discounting the possibility of negative rates in the US, most Fed officials have rejected the idea. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell spoke strongly against the idea in a webcast appearance last week, saying negative rates are “not something that we are looking at.” Other Fed officials have echoed his view. Fed Vice Chair Clarida for example yesterday said that the Committee at large did not favor them and pointed to the minutes of the October 2019 FOMC meeting, where “All participants judged that negative interest rates currently did not appear to be an attractive monetary policy tool in the United States.”

Although the Fed staff concluded in 2011 that negative rates would be possible, and former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke said in 2016 that “negative interest rates appear to have both modest benefits and manageable costs,” there are several reasons why they aren’t under consideration:

- It’s not clear if it’s legal for the Fed to impose negative rates.

- Unique features of the US financial system, particularly the widespread use of money market funds (about $4tn in assets), make negative rates problematic.

- The experience of Europe and Japan don’t provide conclusive proof of the benefits of such a radical departure from traditional practice;

- The US financial system relies more on the corporate bond markets whereas the European and Japanese systems rely more on bank lending. Central bank purchases of bonds therefore have a stronger monetary impact in the US, while measures to prod banks to lend are more effective in Europe and Japan.

Last but definitely not least,

- The dollar’s central role in the global monetary system makes it a different matter altogether for the US to undertake this step

A week ago the market was discounting the possibility of the Fed dipping its toes into negative territory, but the consensus now is that zero is indeed the lower bound.

Canada: Not under consideration The Bank of Canada said that its current policy rate, 0.25%, is “its effective lower bound.” Its last statement said that it “stands ready to adjust the scale or duration of its programs if necessary,” but no mention was made of lowering rates any further. Asked about the issue, Bank of Canada Gov. Poloz recently said, “We don’t like the idea.” Poloz’s successor, Tiff Macklem, agrees. He said recently that negative rates were too disruptive for an already disrupted financial system and added that he was comfortable with 0.25% being as low as the bank would go.

Australia: Extraordinarily unlikely The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Cash Rate is at 0.25% and the Board has pledged not to increase it until conditions have improved substantially. RBA Gov. Lowe said “we are likely to be at this level of interest rates for an extended period.” While this does not constitute an outright rejection of negative rates, Gov. Lowe said it was “extraordinarily unlikely” that the RBA would use that tool. They would first increase their bond purchases, which in fact they have been scaling back recently.

New Zealand: Possible but definitely not imminent. When the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) cut the Official Cash Rate (OCR) to 0.25% on 16 March, the Monetary Policy Committee said the rate “will remain at this level for at least the next 12 months.” That means no move lower as well as no move higher. However, RBNZ Gov. Orr has made it clear that a cut is still a possibility. “We don’t want to go negative at this point; we’re prepared to if we have to but not until a lot later,” he said. “It’s got to jump the hurdles. It’s got to be seen as necessary. It’s got to be seen to be effective, efficient and operationally capable.” By “operationally capable,” Orr means that banks’ systems have to be able to handle negative rates. Deputy Gov. Bascand said the central bank wants banks to be ready for negative rates by the end of the year. The question for RBNZ is whether economic conditions next March will warrant negative rates.

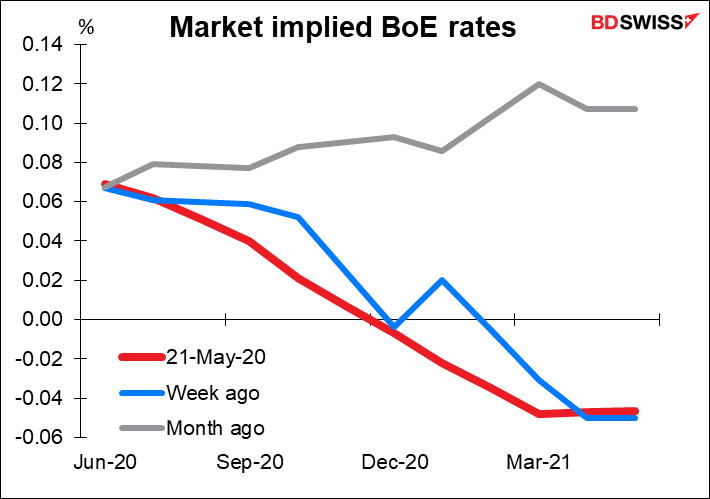

UK: Neither ruled out nor ruled in, whatever that means The Bank of England is the biggest question mark. BoE Gov. Bailey said earlier this week that negative rates are “under active review,” although what that means is unclear. He said just a week ago said that negative rates are “not something we are currently planning for or contemplating.” However, over the weekend BoE Chief Economist Haldane was quoted as saying that the Bank was looking at negative rates, followed a day later by Monetary Policy Committee member Tenreyro saying that they’re not ruling out negative rates. Then Bailey changed his tune. “Given what we’ve done in past few weeks, it should come as no surprise to learn that of course, we’re keeping the tools under active review in the current situation.” But he added that although just because they weren’t ruling things out, “that doesn’t mean we rule things in, either.”

The market sees a small chance of bank rate coming down below zero.

This week’s issue of three-year gilts at a slightly negative rate (-0.003%) suggests that the market does indeed believe negative rates are a possibility in the UK.

Sweden: Not ruled out The Riksbank’s repo rate, its policy rate, was negative from February 2015 until December 2019, when the Executive Board returned it back to zero. At the latest monetary policy meeting on 27 April, the Board decided to keep the rate unchanged at zero, but the minutes noted that “they did not want to rule out the possibility of the repo rate being cut later on to stimulate demand in the recovery phase, and thereby safeguard price stability.”

Norway: Unlikely Norges Bank cut rates to zero on 8 May, the first time ever. While they did not rule out negative rates, Gov. Olsen said, “In the Committee’s current assessment of the outlook and balance of risks, the policy rate will most likely remain at today’s level for some time ahead. We do not envisage making further policy rate cuts.” He expressed skepticism about the utility of negative rates and in particular their impact on financial markets.

As for the three major central banks that do have negative rates currently – the ECB, SNB and BoJ – they’ve shown no inclination to change rates in either direction. That is, while they haven’t necessarily given up on negative rates, neither have they take the opportunity to lower rates further. The last such move was in September 2019, when the ECB cut its deposit rate by 10 bps to -0.50. All three have defended their policies, but if we look at what they do, not what they say, it appears that negative rates are like salt on food: just because a little is good doesn’t mean more is better.

Investment implications: watch GBP, NZD & SEK

Who better to ask about the impact of negative interest rates on the exchange rate than Thomas Jordan, Chairman of the SNB, who had the distinction of implementing the lowest interest rates in history? The SNB cut rates to zero in August 2011, -0.25% in December 2014, and a record-setting -0.75% in January 2015. In a speech in October 2016, Jordan said:

…although negative nominal rates are often perceived as unnatural, the laws of economics are not inverted once the zero lower bound is breached. In principle, taking a policy rate into negative territory has a similar effect to cutting a policy rate in positive territory. In Switzerland, the negative interest rate has its main impact via the exchange rate channel. Together with the SNB’s willingness to intervene on the foreign exchange market as necessary, the negative interest rate policy has prevented further Swiss franc appreciation and has generally helped to reduce pressure on the currency.

Academic research generally bears out that conclusion: negative rates affect the exchange rate exactly as the laws of economics would suggest. It’s not like physics, where approaching absolute zero causes materials to behave weirdly. One study of the question found that “negative interest rates seem to have little effect on observable exchange rate behavior.” That is to say, a cut in rates from 0% to -0.25% would be expected to weaken the exchange rate more or less like a cut from 0.50% to 0.25%. Nor do exchange rates become more or less volatile when rates go negative.

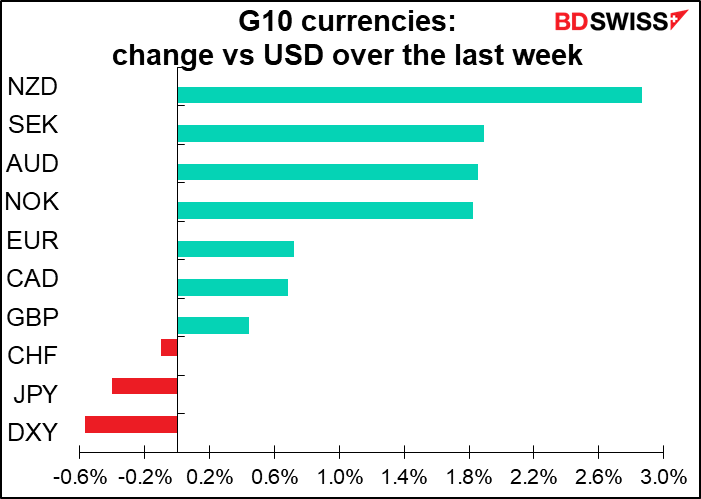

In that case, if any of the central banks currently teetering on the edge do decide to take the plunge, we can expect their currencies to weaken, but not because there’s anything special about negative rates, just that negative rates are lower than positive rates. They therefore present a near-term risk to GBP and a medium-term risk to NZD and SEK.

Next week’s schedule: EC fund proposal, inflation data, Beige Book

The European Commission is expected to reveal its proposal for the EU Recovery Fund on Wednesday. It’s expected to build on Monday’s joint French-German proposal for a EUR 500bn fund financed by joint issuance and distributed as grants. The French-German proposal is a bold move that crosses a previous red line in Europe: joint fiscal responsibility. If it passes – which is by no means certain – it would reduce the risk of a slump in peripheral Europe, notably Italy, and increase the likelihood of a synchronized recovery across the Continent. Over time it would reduce the pressure on national budgets and the ECB and increase the likelihood of some kind of enhanced pan-European fiscal capacity.

Jean Monnet, sometimes called “the father of Europe,” once said, “Europe will be forged in crises, and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises.” This looks like one of those times, if the problem finally brings fiscal integration to match the monetary unification of the Eurozone.

As for next week’s data, the main point of interest next week will be the inflation data from Germany & the EU, Japan, and the US. These figures are likely to corroborate the data that we saw this week from Canada and the UK of slowing inflation around the world.

Germany inflation Thursday is expected to fall below 1%, while the headline rate for the whole EU (Fri) is forecast to move up just one tic to +0.4% yoy, i.e. almost nothing.

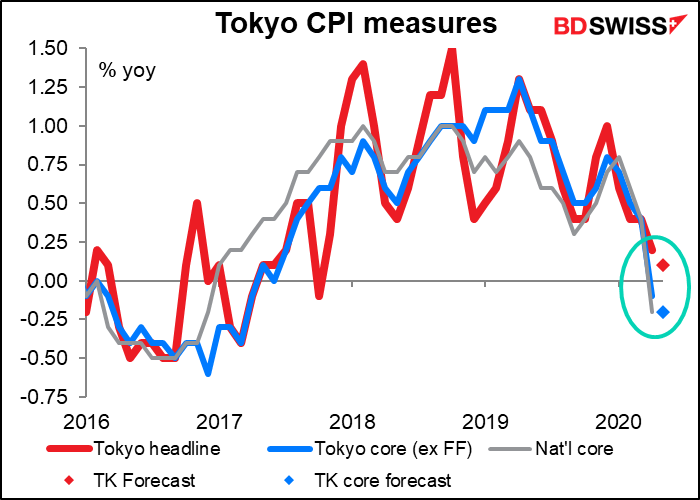

We saw this morning that core nationwide prices in Japan slipped into deflation in April (-0.2% yoy). Now the market expects deflation in Tokyo for May (Fri) to be at least the same.

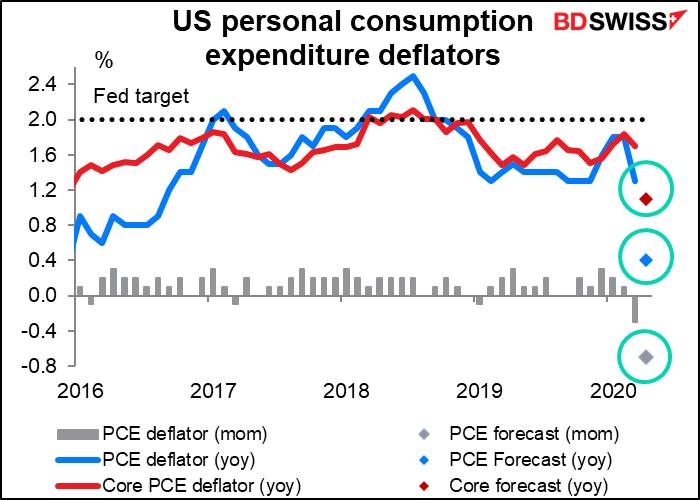

Finally, the US personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator (Fri), the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, is expected to show the second consecutive mom decline. The forecast fall of -0.7% would be the second-steepest on record, after -1.1% in November 2008 (data back to 1959). Meanwhile the core PCE deflator, which is what the Fed looks most closely at, is forecast to slow to just +1.1% yoy, about half the Fed’s target.

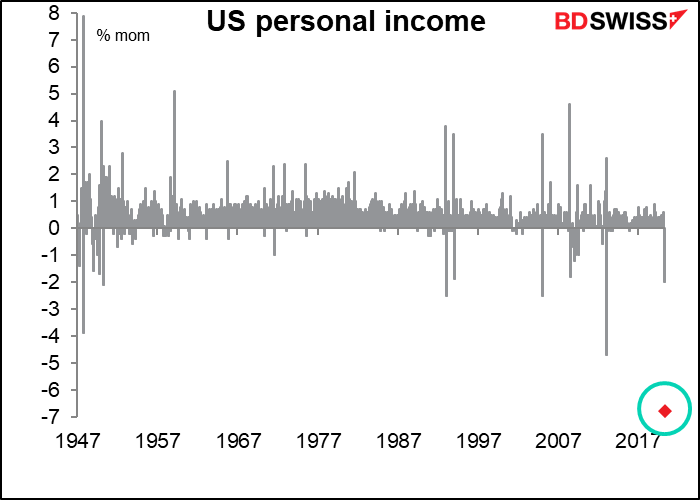

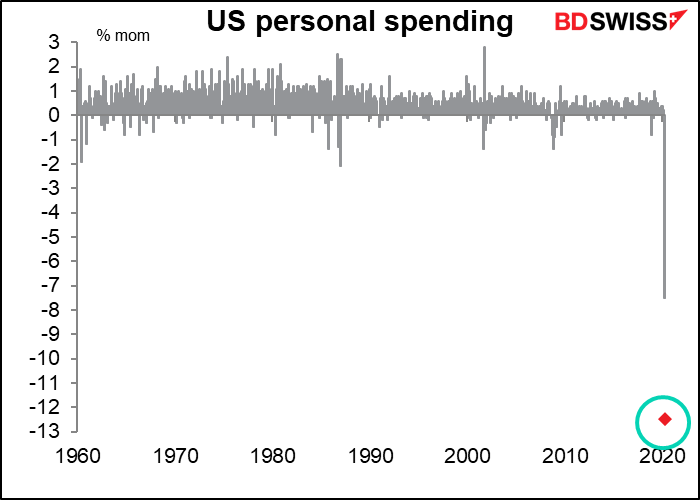

The PCE deflators are part of the US personal income & spending data. These are expected to be off the charts.

Other US data of note out during the week include Conference Board consumer confidence (Tue), Richmond Fed index and the Beige Book (Wed), durable goods orders (Thu), and advance goods trade balance (Fri).

Of course the weekly jobless claims and, more importantly nowadays, the continuing claims will be the stars of the week, as usual.

In addition to the Tokyo CPI figures on Friday, Japan has its usual end-of-month data dump, including employment data and industrial production.

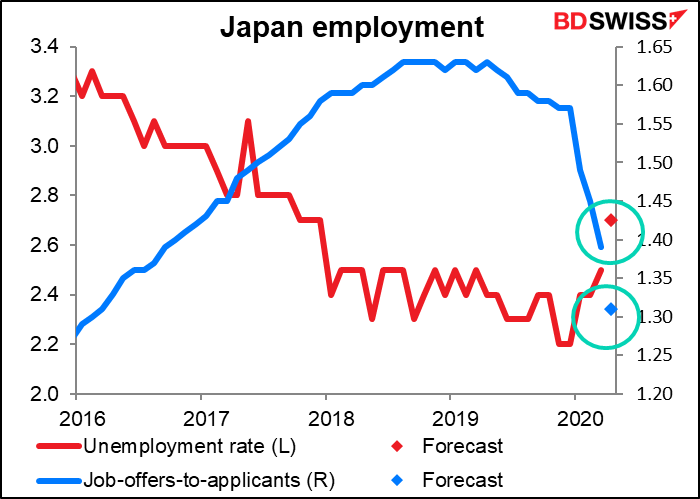

The unemployment rate is only rising slowly, but the job-offers-to-applicants ratio is falling much more rapidly than it rose. That’s a truer picture of the employment situation.

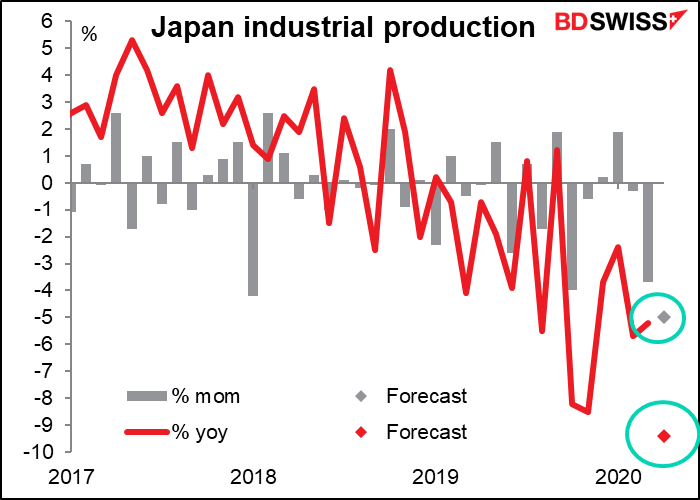

Meanwhile, after the steep 3.7% mom fall in March, Japan industrial production is expected to fall an even steeper 5.0% mom in April. The decline no doubt goes along with the 22% yoy fall in exports during the month.

Finally, some excitement in Canada. Bank of Canada Gov. Poloz will sing his swan song on Monday, his last speech before he leaves the central bank on 2 June. And on Friday, the country releases Q1 GDP.

Monday is a holiday in the US and Britain.