There’s been a lot of chatter recently in the press about whether the explosion in the Fed’s balance sheet and the soaring price of gold are signaling an end to the dollar’s reign as the world’s main reserve currency. I don’t think that’s likely to happen any time soon, or even not so soon. That’s a shame because contrary to what a lot of people seem to believe, it would be a good thing for the US if it did happen.

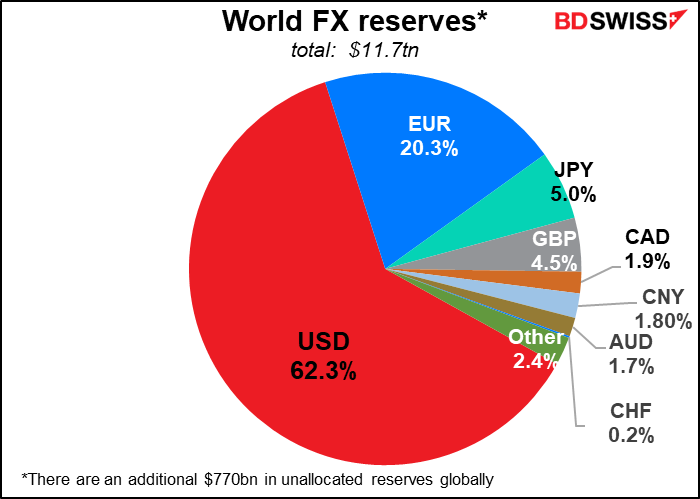

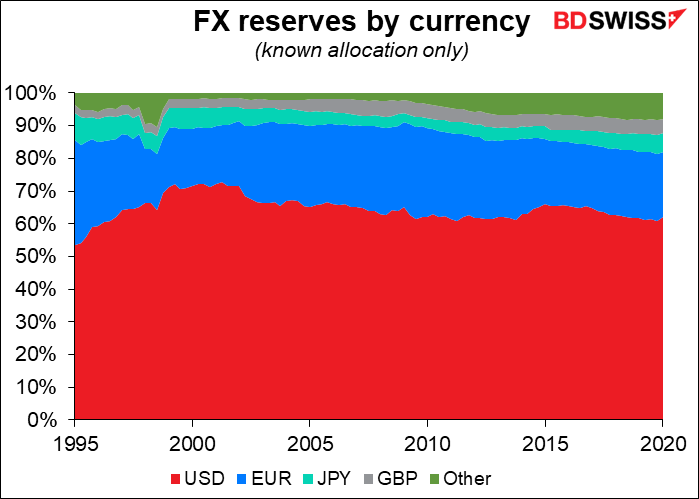

As far as we know, the dollar accounts for 62% of reserves, EUR is 20%, and then there are the rest. Take a look at the IMF’s breakdown of reserves by currency at http://data.imf.org/?sk=E6A5F467…

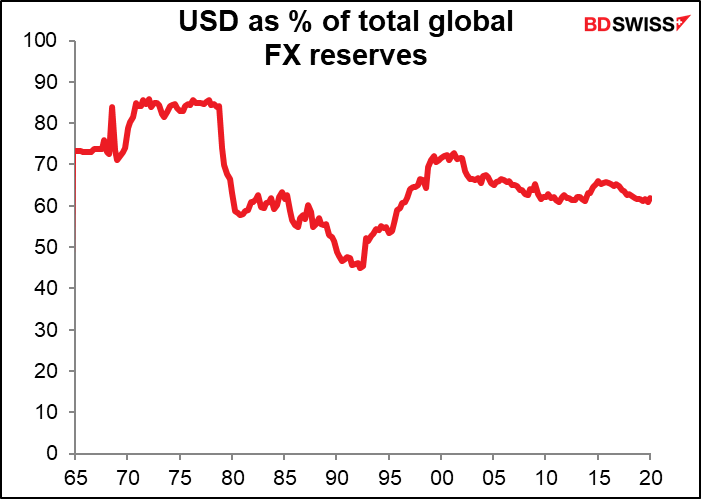

That percentage has been fairly steady over the years. It’s down from the recent peak of 73% in 2000, but still up from 45% in 1990.

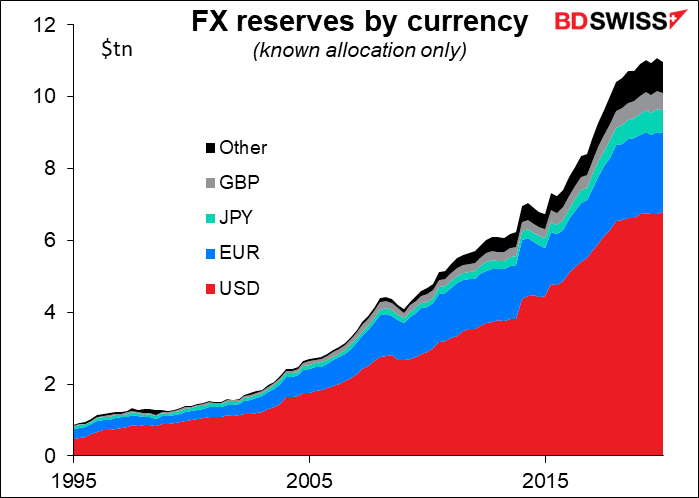

Talking about it in percentage terms though masks the tremendous increase in the amount of reserves held in dollars. In Q2 2001, when the dollar hit its recent peak of 72.7% of total allocated reserves, there were $1.10tn in known USD reserves. Now at 62.0% there are $6.79trn in USD reserves – an increase of over 6x. (EUR figures before 1999 are the sum of known EUR-member legacy currencies.)

By the way, it’s not the euro that’s taking “market share” away from the dollar – it’s more a general diversification of reserves. The euro’s share peaked at 28.0% in Q3 2009 and is now 20.0%. The yen’s share on the other hand has almost doubled from 2.9% in Q3 2007 to 5.7% today, while CAD and AUD went from nothing to 3.3% and CNY now takes 2.0%.

No one has decreed that countries have to keep their reserves in dollars. This system hasn’t been foisted on the other nations of the world against their objections. It could end tomorrow if other countries chose to keep their FX reserves in other currencies. It’s just the result of individual decisions by each country.

Why have most countries have elected to hold the bulk of their reserves in USD? To fulfill this role, a country has to have:

- large, liquid financial markets capable of taking huge investments (there are currently at least $6.3tn – that’s trillion dollars – in international currency reserves held in USD, and probably closer to $7.2tn);

- a reputation for safety and rule of law, so that other countries are willing to invest billions and billions of dollars in that country’s government securities; and

- a willingness to run current account deficits indefinitely, since that’s the counterpart of a financial account surplus.

I think you’ll find that at the moment, there is only the US that fits all three criteria, and I don’t see any other country volunteering to take its place any time soon.

What other country’s bond market could take even half that amount?

- Only Japan has a big enough bond market, but they have shown zero interest – in fact significant opposition – to having their currency play this role. That’s because they insist on running a current account surplus, so the last thing they want is financial inflows. They’ve gotten upset before when foreign central banks started buying their bonds and pushing up the value of the yen.

- The Chinese government bond market is also large and growing, but of course China has an estimated $1tn or more in USD reserves – where can it put that money besides USD? Plus of course the problem again of the current account surplus.

- The EUR can’t take over that role, because its bond markets are too fragmented – there are only national bond markets, not one large Eurozone bond market. The biggest EUR bond market is Italy, which nobody particularly wants to hold nowadays without an implicit European Central Bank (ECB) put. Plus the ECB has bought a lot of the outstanding bonds, meaning it would be difficult to move the funds into EUR without causing major disruption of markets and dreadful price movements in markets that are already trading mostly at negative yields. And again, there’s the current account problem: Germany’s economy is dependent on exports, so they might not like the appreciating currency that goes along with a major reserve role.

- The recent decision of the European Commission to issue bonds that are liabilities of the Eurozone as a whole and not just one country is a start, but the size is much too small (EUR 750bn) – not to mention that the ECB is likely to buy up half of them anyway.

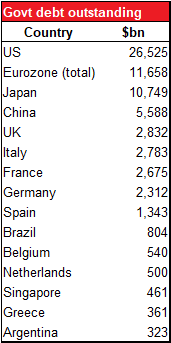

(See table at bottom for the size of the world’s bond markets.)

On the contrary, most countries fight to prevent their currency from being held as a major reserve currency, since that causes the currency to appreciate, exports to fall, growth to slow, and unemployment to rise.

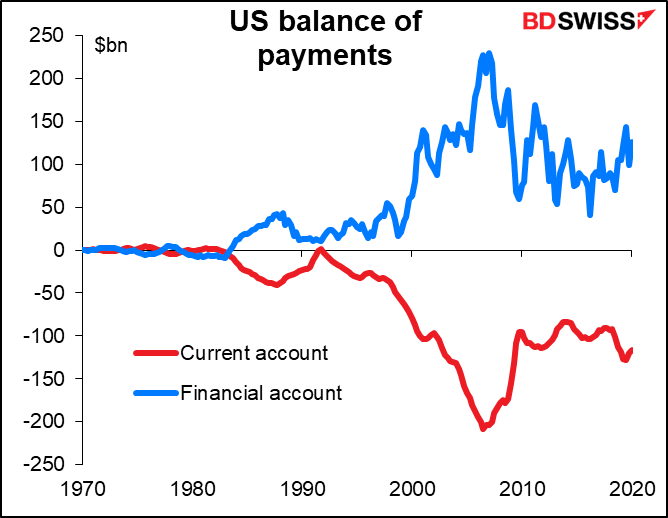

You see, in order to accumulate foreign exchange reserves, the rest of the world buys US financial assets — mostly Treasury bonds and US government agency bonds. This means the US runs a financial account surplus (surplus in this case means net money coming in.) But if a country runs a financial account surplus, by definition it has to run a current account deficit (unless the government intervenes like crazy, as in China). That’s because the money coming into a country has to equal the money going out. Otherwise, how can people abroad get the dollars necessary to buy US bonds in the first place? Money coming in to buy US bonds gets recycled when US consumers buy foreign goods. That’s how foreigners get the dollars necessary to buy US bonds. Or looked at another way, the way US residents get the foreign currency necessary to buy overseas goods is by selling bonds abroad. They’re two sides of the same coin.

In other words, the fact that the USD is the world’s major reserve currency is one of the main reasons why the country has run a trade deficit for most of the last 30 years. (This is known as the Triffin dilemma — a dilemma identified in the 1960s by the economist Robert Triffin, who realized that any country that dominated world FX reserves would have a consistent current account deficit that would gradually undermine the value of that currency.)

What would happen then if these scare articles we’ve been reading recently were correct and the USD was indeed losing its pole position? Probably its value would fall, US exports would be more competitive, and more people in the US would have jobs making goods for exports. US government bond sales might fall, but income tax receipts would go up and welfare spending would go down, meaning the government would have to issue fewer bonds in the first place.

On the other hand, probably fewer people in China, Germany and Mexico would have jobs making things for export to the US. Do you think that’s a good thing or a bad thing? Probably depends on whether you work in a US or Chinese factory.

While some people have said that the use of the dollar as the world’s major reserve currency is an “exorbitant privilege” because it allows the US to pay its bills in its own currency, other people argue that it’s actually an “exorbitant burden” for just this reason. For example, Prof. Michael Pettis said in an article written four year ago but appropriate still to today’s discussion: The Titillating and Terrifying Collapse of the Dollar…Again

Conspiracy theorists are certain that there is some nefarious benefit that the US receives, along with the prestige, of controlling the world’s reserve currency, in spite of what should be obviously contrary evidence. While we all understand the reasons why countries engage in currency war, we are unable to understand that currency war is nothing more than the actions of a country determined to reduce its own share of “exorbitant privilege”, and force it onto the rest of the world, which in practice usually means the US. In the end the confusion over exorbitant privilege is simply part of the larger confusion that among other things drives continental machinations against the dollar and “Anglo-Saxon” financial hegemony.

McKinsey Global Institute estimated that in 2007/08—a “normal” year for the world economy – the net financial benefit to the US of having the dollar as the chief global reserve currency was between about $40bn and $70bn, or 0.3%-0.5% of US GDP. In a “crisis” year, such as the year to June 2009, it estimated that the benefit fell to $5bn-$25bn because the dollar’s “safe haven” aspect caused it to appreciate. One can easily imagine how a weaker dollar could boost exports by significantly more than $70bn.

As former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke said, “Overall, the fact that English is the common language of international business and politics is of considerably more benefit to the United States than is the global role of the dollar. The exorbitant privilege is not so exorbitant any more.”

Note: here’s a table of the size of the world’s major government bond markets. While the Eurozone bond market as a whole is quite large, it’s divided among many smaller national markets, the largest of which as I mentioned is Italy. This is important because central banks don’t keep their FX reserves in a safe piled up with dollar and euro bills; they invest them, mostly in government bond markets. Thus the size and liquidity of bond markets are an important feature to take into account when deciding where to stash your reserves. Research has shown that some 40% of EUR-denominated reserves are in Bunds even though Bunds represent only 20% of total EUR government bond markets. The EUR bond market as a whole is large, but the AAA-rated EUR bond market is only a small part of the whole. (This is one reason why the market is so excited about the new bonds to be issued by the European Commission to pay for the pandemic recovery program, but that will be only EUR 750bn, and the ECB will probably buy up much of that anyway.)