The title of this week’s comment could certainly refer to the US political situation, but I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about the outlook for the global economy, which, according to three central banks, is getting better, as the Beatles sang.

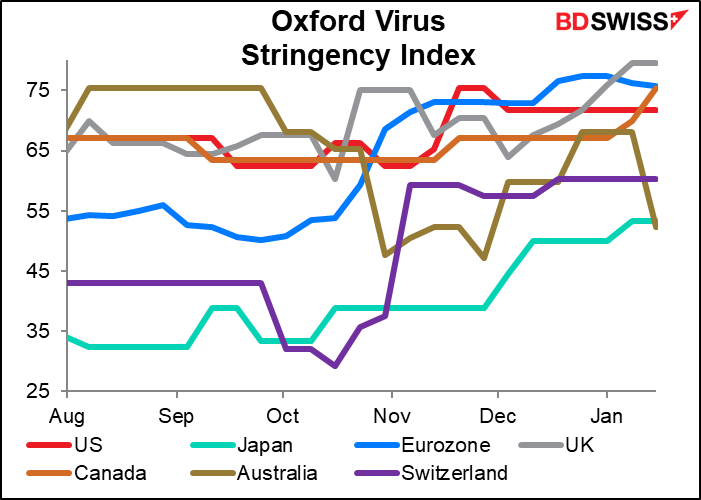

Not however getting better all the time, as the song goes. On the contrary, “The economic recovery has been interrupted in many countries as new waves of COVID-19 infections force governments to re-impose containment measures,” as the Bank of Canada said. That’s clear from the Oxford Virus Stringency Index, an index of how stringent or loose a country’s restrictions against the pandemic are. Many countries started tightening their measures in the autumn, and recently another round of mask-tightening has been occurring worldwide.

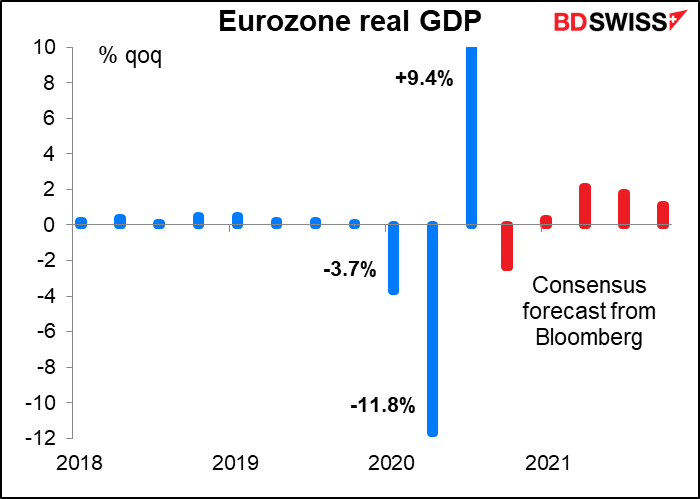

The result is likely to be lower growth in the near-term. “Canada’s economy had strong momentum through to late 2020, but the resurgence of cases and the reintroduction of lockdown measures are a serious setback. Growth in the first quarter of 2021 is now expected to be negative,” the Bank of Canada said. In Japan, “downward pressure stemming from the impact of the resurgence of COVID-19 is likely to remain strong for the time being,” according to the Bank of Japan. Indeed — the country just declared a State of Emergency. And in the Eurozone, “The renewed surge in coronavirus (COVID-19) infections and the restrictive and prolonged containment measures imposed in many euro area countries are disrupting economic activity… Output is likely to have contracted in the fourth quarter of 2020 and the intensification of the pandemic poses some downside risks to the short-term economic outlook,” according to ECB President Lagarde. She later said that the decline in output in Q4 2020 “will travel into the first quarter” of 2021.

But that’s now. Things are bound to get better as more and more people are vaccinated. “However, the arrival of effective vaccines combined with further fiscal and monetary policy support have boosted the medium-term outlook for growth,” said the Bank of Canada, as it raised its forecast for 2021 growth. Japan also upgraded its FY2021 (year beginning April) forecast, “reflecting the effects of the government’s economic measures in particular.” “Japan’s economy is likely to follow an improving trend with the impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) waning gradually,” it said. And in the Eurozone, “Looking ahead, the roll-out of vaccines, which started in late December, allows for greater confidence in the resolution of the health crisis…Overall, the risks surrounding the euro area growth outlook remain tilted to the downside but less pronounced. The news about the prospects for the global economy, the agreement on future EU-UK relations and the start of vaccination campaigns is encouraging…”

This is in fact the general view from the markets too, I’d guess. For the EU, the markets expect that output shrank in Q4 last year and will be barely changed (+0.4% qoq) in Q1 this year. But it gets gradually better from there. I wouldn’t be surprised to see the Q1 forecast revised down over the next few days. For Japan, economists expect a decline in output this quarter but a gradual increase thereafter. Ditto for Canada.

As it stands now, the market expects US output to return to pre-pandemic levels by Q3 of this year, Canada by Q4, Japan just barely by Q2 of next year, and the Eurozone and UK…not by Q2 2022, which is when I run out of forecasts. We’re likely to get revisions to these forecasts over the next few weeks. I would suspect economists to pencil in a steeper decline in the first half of this year but a steeper recovery in the second half, for faster growth overall.

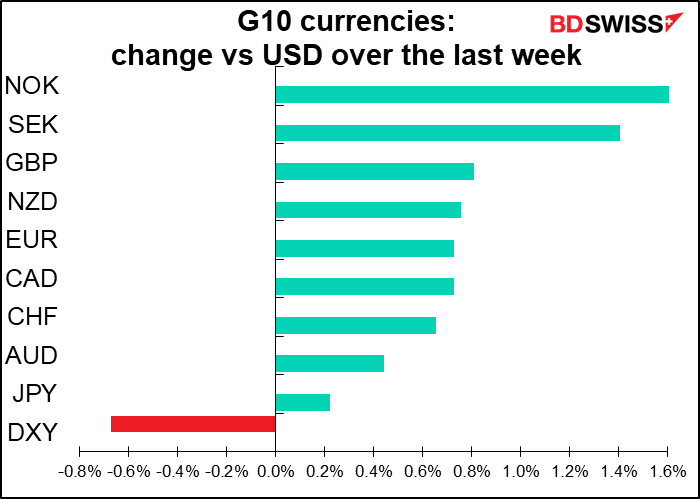

What impact is this likely to have on currencies? From what we can gather, none for now for the Eurozone or Japan. Lagarde repeated her mantra that the ECB “will continue to monitor developments in the exchange rate with regard to their possible implications for the medium-term inflation outlook,” but with EUR/USD steady and no change in policy, there was no major impetus one way or the other. March may be a different matter, as they’ll have new forecasts then and can consider “recalibrating” their toolkit once again. Same for BoJ, which will announce at the March meeting the results of its “assessment” of possible policy measures. (Reuters reported that they may take some steps to loosen their grip on the stock and bond markets at that meeting.)

But the Bank of Canada is a different story, and its behavior could be an indication of what’s going to happen in the future with other central banks.

They continued to say that they will keep interest rates steady until their 2% inflation target is “sustainably achieved,” which they don’t expect to happen “until into 2023.” No change there. However, they did change their guidance with regards to their CAD 4bn-a-month bond purchases.

In December they said, “…the Bank will continue its QE program until the recovery is well underway and will adjust it as required to help bring inflation back to target on a sustainable basis.” This implied that they’ll increase it if necessary.

This month they changed it to “…the Bank will continue its QE program until the recovery is well underway. As the Governing Council gains confidence in the strength of the recovery, the pace of net purchases of Government of Canada bonds will be adjusted as required.” This implies that they’ll cut back on the bond purchases when they think it’s appropriate.

In the words of Fed Chair Powell, they’ve begun “thinking about thinking about” tapering down their bond purchases.

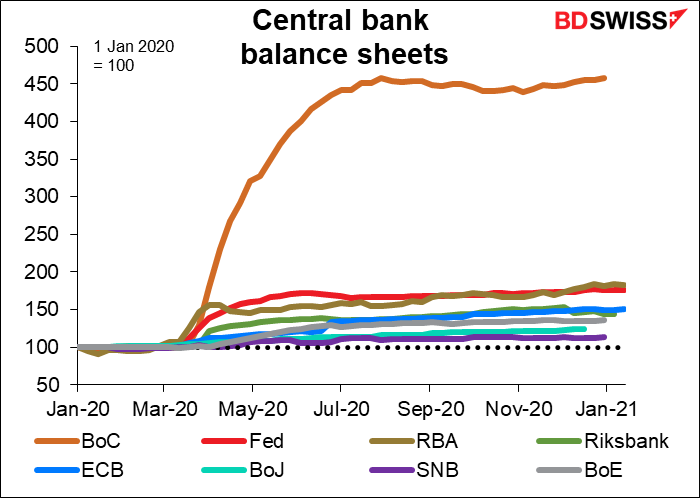

The Bank of Canada is certainly the appropriate central bank to start thinking about this. The expansion of their balance sheet over the last year has left the other major central banks in the dust, up 4.6x what it was at the beginning of the year, vs 1.8x for #2, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and 1.75x for #3, the Fed.

If other central banks also started thinking about this, how would it affect their currencies? We can gauge that by looking at the difference between their actual policy rates and their “shadow” policy rates. The “shadow” policy rates take into account the impact that their quantitative easing programs have on their bond markets and therefore on overall monetary conditions. What we see is that its massive QE program has had relatively little impact on Canadian monetary conditions compared to other countries, so unwinding that policy should have relatively little impact on the currency. The biggest impact of extraordinary monetary policies has been in New Zealand and Australia. If the Reserve Bank of New Zealand makes a similar change at its next policy meeting (Feb. 24), that could have a large impact on NZD.

On the other hand, this may also suggest why the Bank of Canada hinted about tapering at this early stage – because they have the least to lose from it. Tapering off their bond purchases will have the least effect of any of those central banks. In that case, the RBNZ would be expected to be the last to move, and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) might be the next to go – except they’re worried about the exchange rate and so will never move before the ECB does. The Bank of England is not going to tighten policy while the country is still adjusting to its new relationship with its major trading partner and discovering just what the “law of unintended consequences” is – who would’ve thought the supply of pallets would be a major concern for monetary policy? Next in line then would be the ECB, which as mentioned above may “recalibrate” at its next meeting on March 11th.

Which brings us to next week’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting…

Next week: FOMC, Davos, US & Germany Q4 GDP, US personal income & spending, and inflation data from Australia, Germany, Japan and US (PCE deflator)

There’s a busy week of events & indicators scheduled for next week. The highlights will be Wednesday’s FOMC meeting and the week-long Davos forum, which this year will be held virtually (no more people flying to Switzerland on their private jets to discuss global warming).

The first FOMC meeting of the year is always one of the most important. First off, there is a lot of housekeeping chores to do: the annual rotation of the voting for the regional bank presidents, shuffling the membership on sub-committees, and reaffirming the Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy. Since the latter was totally revised just in August, there should be no changes at this early date.

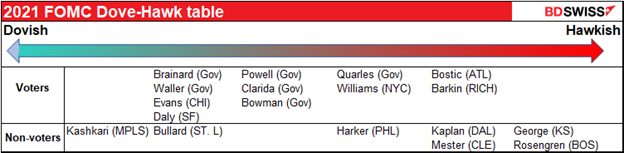

The dove/hawk balance shifts modestly more dovish. Although uber-dove Kashkari is no longer a voting member, the FOMC gets a new member from now, Gov. Waller, the last appointment by He Who Must Not Be Named. Waller was chosen specifically because he’s a dove. I rank him with his former student, St. Louis Fed President Bullard. Also the dovish Evans is replacing the hawkish Mester. (Note that this ranking is purely subjective and many people rank them differently, although I think there’s consensus on Kashkari and George at the extremes.)

Despite the changes though I don’t expect the FOMC meeting to be any more exciting than the average BoJ meeting, which is to say not very.

I expect that the statement may follow the pattern of the other central banks in downgrading the immediate view but upgrading the longer-term view. The recent fall in nonfarm payrolls and rise in initial jobless claims will certainly temper their view on the current situation and near-term prospects for the economy, but the vaccine roll-out and the new administration’s commitment to more fiscal stimulus may lead them to be more optimistic about the future.

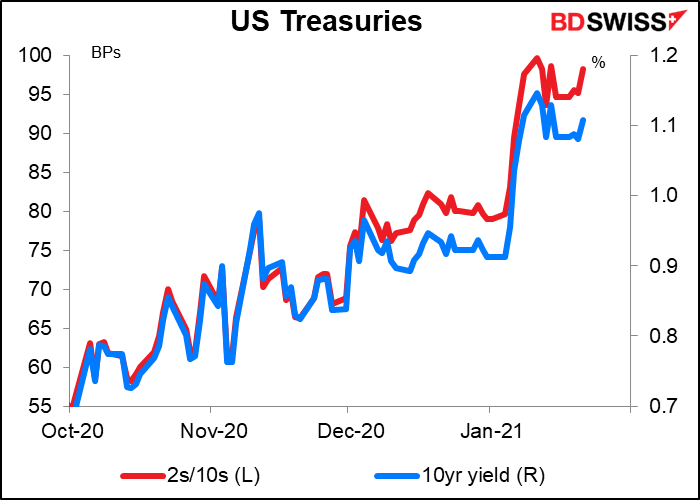

In his press conference, Powell may emphasize this optimism about recovery, but is likely to remain cautious about prematurely considering withdrawing support lest he spook the markets. There have been a variety of comments recently by FOMC members about the speed of the recovery and when the Fed might be able to start reducing (or “tapering”) its $120bn-a-month bond purchases. Some of the more hawkish comments caused a sell-off in Treasuries, steepening of the yield curve and a stronger dollar. I doubt if this is what they want. On the contrary, the consensus seems to be “not now, John.” Fed Chair Powell’s view: “Now is not the time to talk about exit …” He’s almost certain to refer to the guidance that any change in the Fed’s balance sheet will depend on “substantial further progress” toward the Committee’s goals

The annual Davos Forum will be held this week, virtually instead of in the mountains of Switzerland. I don’t know how it will work. Most years this is a source of endless interviews and commentary by the great and the good, who assemble in this skiing resort to remind each other how great and good they are and to work out the solutions to all the world’s problems – which oddly enough never include higher taxation on wealthy individuals. (You can hear Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s famous comments on that topic from 2019 here.) You can see the 2021 agenda here. There will be live sessions from 0700 GMT to 1800 GMT every day.

As for the data, I think the major items will be the US Q4 GDP on Thursday and Germany Q4 GDP on Friday. US GDP is expected to be up 4.3% qoq SAAR (+1.1% qoq) while Germany’s is expected to be unchanged qoq. The German forecast could be revised down though in light of what ECB President Lagarde had to say yesterday.

We could see EUR/USD move a notch lower if this results in Eurozone growth forecasts being revised down more than US growth forecasts.

The other major US indicators coming out during the week are the personal income & spending figures on Friday. They’re forecast to show a tiny rise in income and a larger fall in spending. I’m surprised at the forecast rise in income – I thought that some people lost their unemployment benefits in December. I’m not surprised at the expected fall in spending though as many people thought they were going to lose their unemployment benefits and no doubt conserved what few pennies they had left. Things are likely to be better in January though.

Friday is the last working day of the month (already!) and so we get the usual end-month data dump from Japan: employment data, industrial production, and this month Tokyo consumer prices.

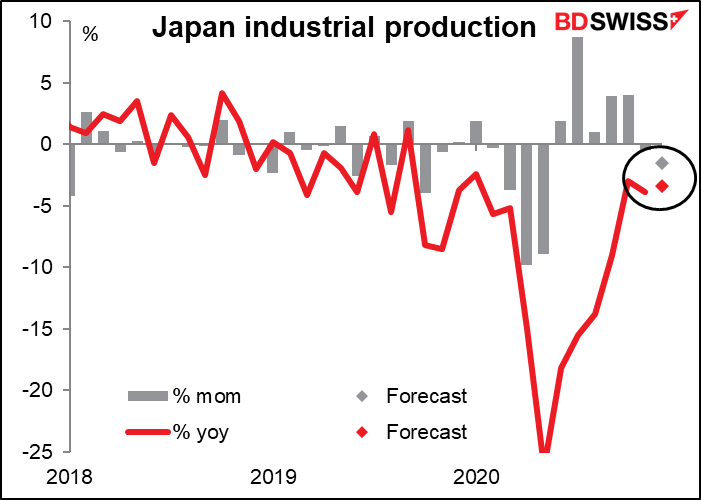

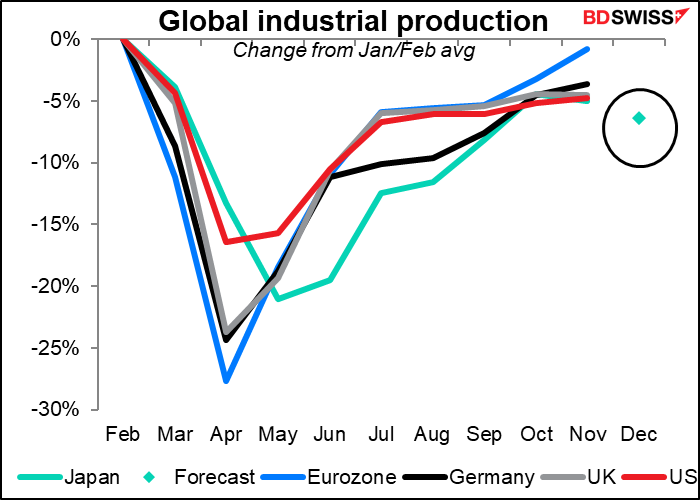

Industrial production is probably the key indicator here. It’s expected to fall from the previous month.

That’s not very good. Japan seems to be lagging behind the rest of the world in the recovery of its industrial production. That could set off some risk aversion that would be positive for the yen, oddly enough – or it could raise thoughts that maybe the Bank of Japan would be less willing to pare back its help for the markets at its March meeting, which would be negative for the currency.

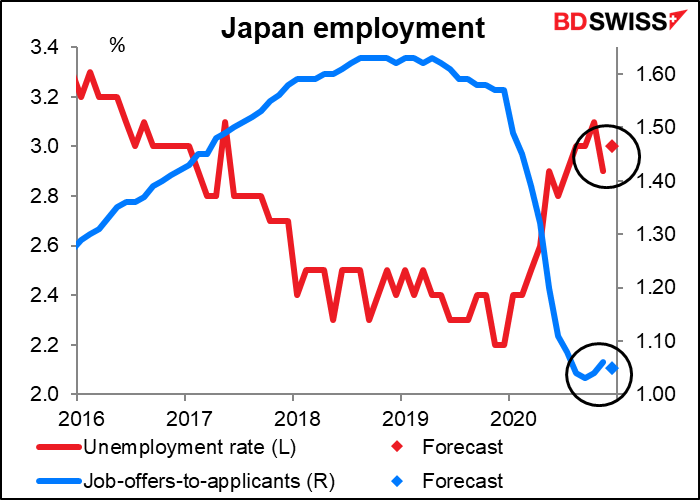

I would tend toward the latter, especially as Tokyo consumer prices are expected to remain in deflation (although a bit less) and the jobless rate is expected to tic up while the job-offers-to-applicants ratio tics down.

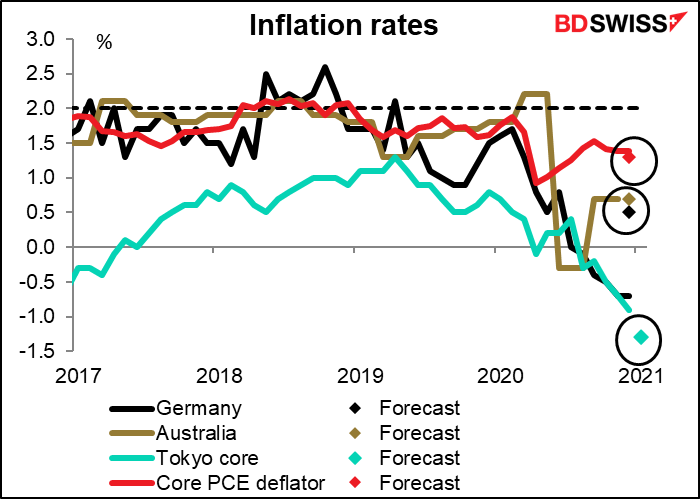

Finally, in addition to the Tokyo CPI data we get CPI for Australia and Germany, plus the personal income & spending data from the US is accompanied by the personal consumption expenditure deflators, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauges. The forecasts are for these to show a further slowing of inflation – that may help to temper much of the “tapering” talk that we’ve been hearing recently, particularly from the US. Germany however is expected to show a jump from deflation back to modest inflation.