Rates as of 04:00 GMT

Market Recap

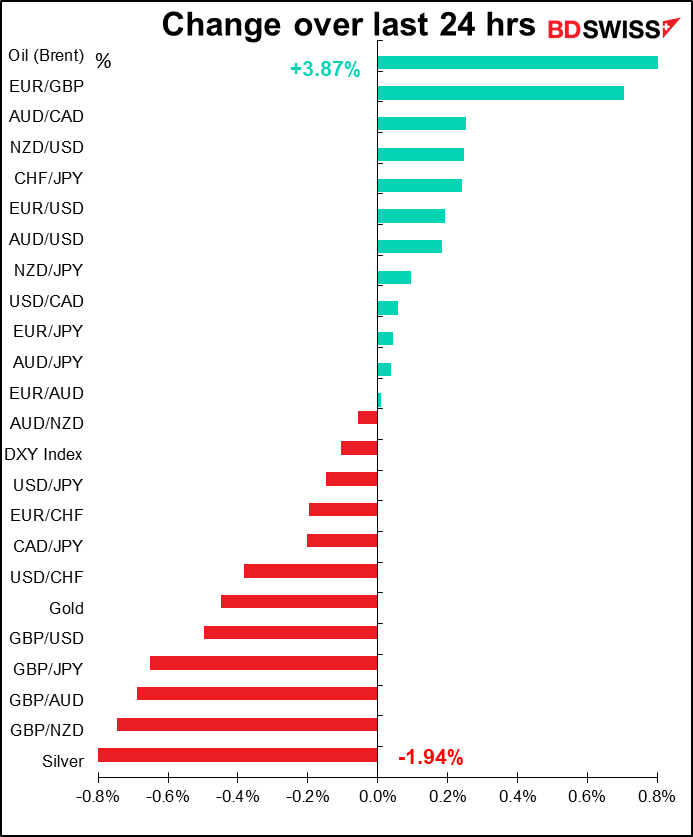

Collapse of the pound! GBP was the outstanding mover yesterday after Bank of England Gov. Bailey said that the Bank is keeping all its policy options open and is not ruling out negative interest rates.

What amused me though was that when asked about negative rates he said “Given what we’ve done in past few weeks, it should come as no surprise to learn that of course, we’re keeping the tools under active review in the current situation.” Apparently he’s wrong – it did come as a surprise to some people. How else can we explain the pound’s movement? Yet just a few days ago, BoE Chief Economist Haldane was quoted as saying that the Bank was looking at negative rates, followed a day later by Monetary Policy Committee member Tenreyro saying the same thing – that they’re not ruling out negative rates. So why did his comments affect the market so much? Because up to now, Bailey has been less enthusiastic about negative rates than his colleagues. Just a week ago, he said “It is not something we are currently planning for or contemplating.” Clearly they are now contemplating it, although Bailey added that just because they weren’t ruling things out, “that doesn’t mean we rule things in, either.”

The market however is indeed pricing in at least a chance of negative rates in the UK.

Yesterday’s slowdown in UK inflation, with headline inflation falling outside the Bank’s area of tolerance, makes the issue all the more pressing.

Furthermore, the debate about negative rates became even more urgent yesterday after the government issued its first bonds with negative rates (GBP 3.75bn of 3-year gilts at an average rate of -0.003%).

The negative rates at yesterday’s auction highlight why negative rates are suddenly a big issue for the Bank. The problem is that if gilt yields are negative but the central bank’s deposit rate isn’t, then banks will find it more attractive to deposit their money with the central bank than to buy gilts and the government may find it difficult to meet its borrowing target

On the other hand, negative lending rates at the central bank would present the opposite problem. Let’s say that the Bank’s lending rate goes negative. That means instead of commercial banks paying money to borrow from the central bank, the central bank pays the banks to borrow from it. In that case, commercial banks can just borrow money from the central bank and invest it in government bonds and make the carry (the difference between their funding cost and the return on their investment) without having to go through all the fuss and bother of lending to people and companies.

These problems are why the European Central Bank (ECB) has set its deposit rate at -0.5% but kept its refinancing rate at 0%.

US markets are also discounting negative rates, but yesterday’s FOMC meeting minutes showed little interest in the idea. Negative rates were mentioned just once, in the opening summary: “Against this backdrop, market participants generally expected the target range for the federal funds rate to remain at the effective lower bound for the next couple of years. Respondents to Desk surveys attached almost no probability to the FOMC implementing negative policy rates.” Of course this meeting took place a few weeks ago and conditions change quickly nowadays, but it’s clear from the minutes that the question wasn’t a major one at their last meeting.

The main news from the minutes was that the Fed’s policy review is expected to conclude later this year and they feel the need to provide more guidance on QE purchases, including whether to tie future actions to specific dates or economic outcomes and whether to cap Treasury yields as a reinforcement. Most of them currently prefer QE while only “a few” members support capping rates. But beware: in the long term, financial repression may be the only way to reduce debt burdens if inflation doesn’t pick up.

The Fed is also clearly worried about the risk of a second wave of virus infections.

Some Twitter summaries of the minutes:

Fed minutes: We will never raise rates again

Fed minutes redacted version: We’re totally screwed but we can’t tell anyone

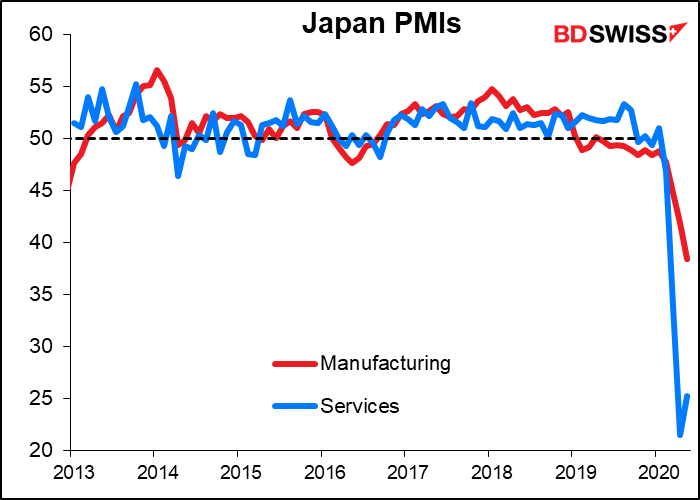

Overnight, Japan’s manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) fell further, while the service-sector PMI bounced back only a little.

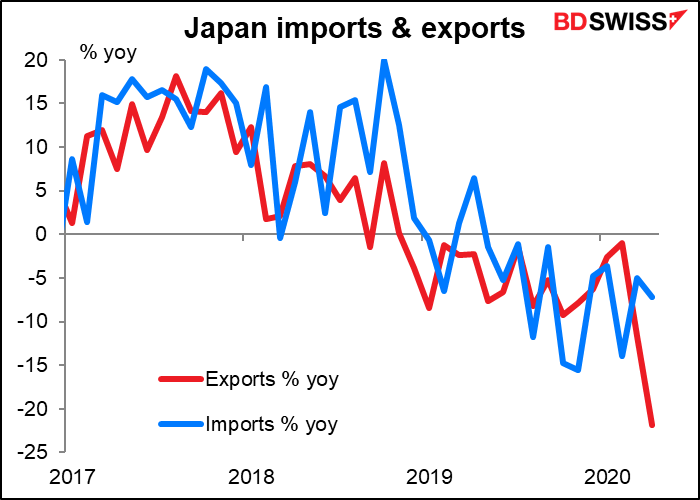

This followed an enormous (22%) decline in exports in April, the steepest decline since the 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis (and indeed we have to go back to 1953 to find anything steeper than that, although in June 1986 exports were down almost as much —- 20.9% yoy). Falling retail sales and delayed investment globally naturally put the brakes on Japan’s exports. The country’s trade account – and therefore the yen – could be in trouble if things continue like this.

Today’s market

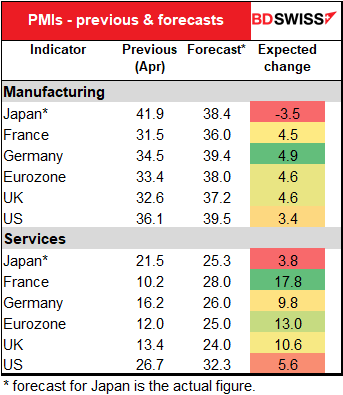

We get the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for May for Europe and the US despite the fact that several of the European countries are on holiday today. The figures will give us some clue as to how the economies are faring as they begin to emerge from lockdown. As you can see, expectations are that a) services will rebound more than manufacturing, b) nonetheless services will still be way below manufacturing, and c) Europe will rebound more than the US, although d) the US will remain well above Europe in terms of services anyway.

Note though that Japan’s manufacturing PMI fell further, while the services PMI only improved a little bit (the “forecast” for Japan in this table is the actual figure), so this improvement is not a foregone conclusion. On the other hand, Japan’s PMIs last month were both significantly higher than the European ones, so it might not have that much predictive power – today’s figures simply brought it into line with what people expect the other countries to be at.

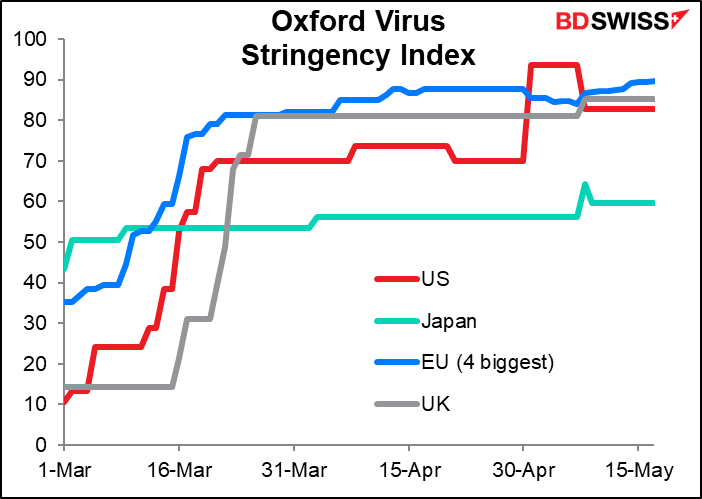

I suspect that the reason why US services are fairing “better” than European – if we can even say such a thing, with PMIs at these levels – is because the lockdown in the US hasn’t been as severe as in Europe. I expect the US to come out of lockdown faster than Europe too, but the positive impact of that on the economy and the dollar may well be offset by a second wave of virus outbreaks.

The Philadelphia Fed business outlook survey is expected to rebound notably from last month’s level, which far below the 2008/09 low and indeed was the lowest in nearly 40 years. Last week’s Empire State index snapped back from a similar low and so it wouldn’t be surprising to see the Philly Fed move similarly. Make no mistake though: the absolute level is still dreadful. But at least it’s not getting worse.

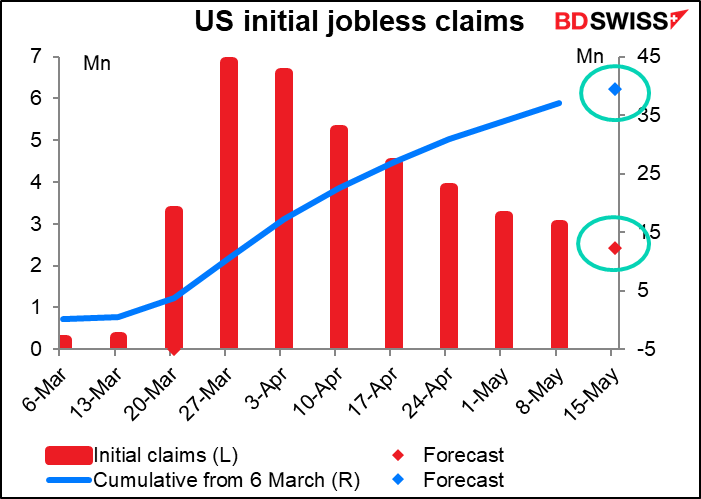

Now we come to the focus of the day: initial jobless claims. They seem to be leveling off rather than continuing to decline, which is disappointing. Leveling off at around 2mn a week is dreadful.

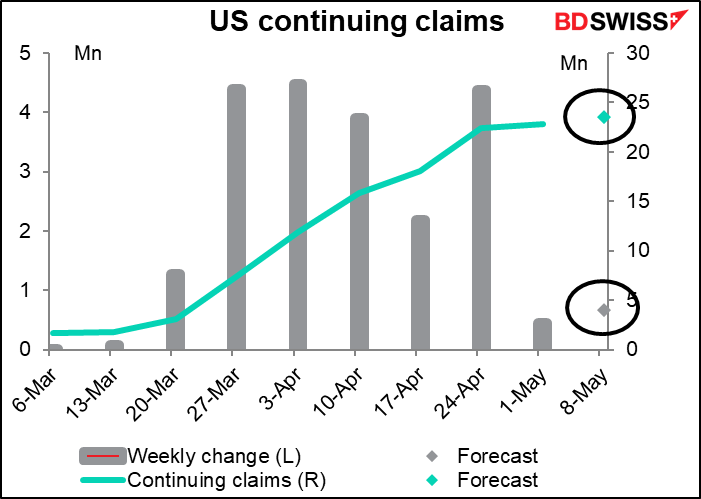

On the other hand, there is some good news from the continuing claims. Those also seem to be leveling off, and the number of new claims every week has fallen to a pretty low level. Given that over 2mn people a week are filing their first claims, but the number of people who’ve filed before and are continuing to claim is only growing by around 500,000 a week, it suggests that 1.5mn people a week are coming off the unemployment rolls – good news. I think we should start to watch continuing claims more closely than initial claims to see how the overall flow in and out of employment is going.

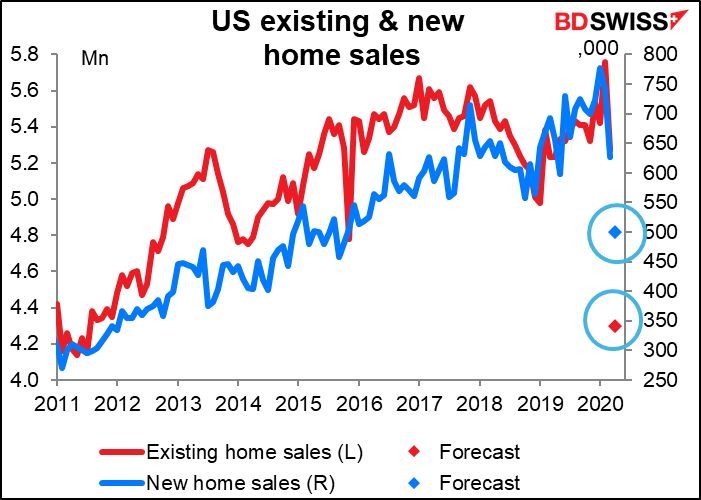

Existing home sales, which plunged in March, are expected to plunge in April back to a level last seen in July 2011 – almost nine years of increase gone in two months. Are you surprised? Probably not. Every statistic is like that nowadays. Next week’s new home sales are expected to fall back to the levels of November 2015.

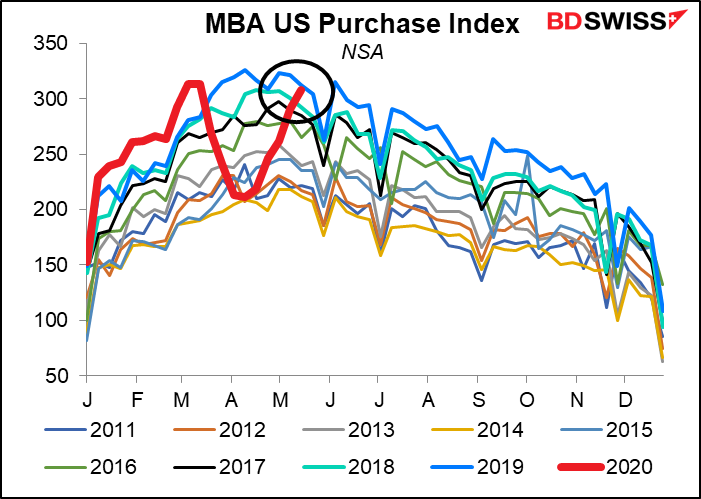

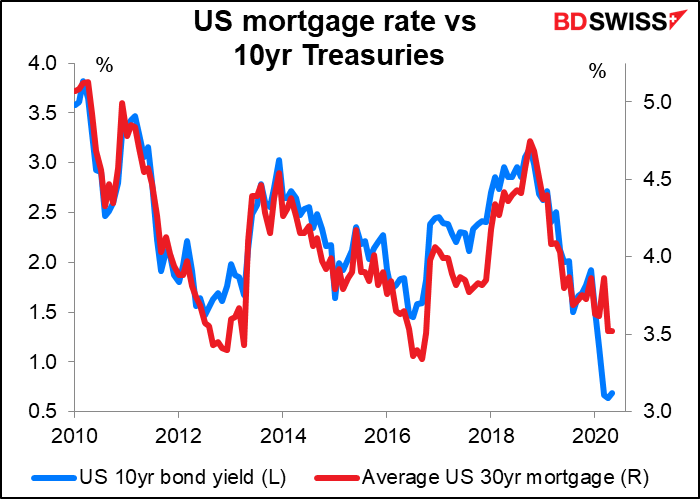

But looking at yesterday’s MBA mortgage applications, which were back to the highest levels seen in the last couple of years, I’d say that this plunge in housing sales is only temporary

People seem to be taking advantage of the fall in mortgage rates, despite the fact that so many don’t have jobs.

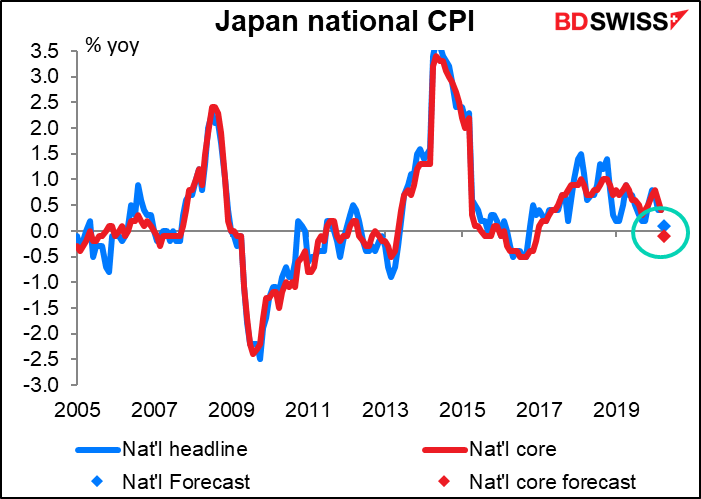

Overnight, Japan’s national consumer price index (CPI) comes out. This isn’t that market-affecting; the Tokyo CPI, which comes out two weeks earlier, is a pretty effective substitute, and besides, everyone knows the Bank of Japan has stopped targeting inflation, so what does it matter anyway? But I think this month’s figure may have some symbolic importance: the Japanese version of core inflation (which excludes fresh foods) is forecast to go slightly negative. Twenty-four years of interest rates at or near zero, and still deflation.

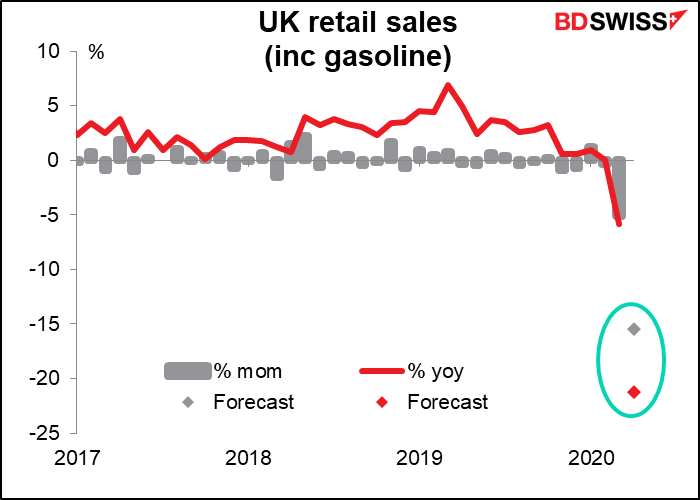

Friday morning once again we get some early British indicators.

Britain went into lockdown on 23 March. Is it any wonder that UK retail sales are expected to have plunged in April? This is what’ s happening everywhere. Same here, too.

I thought I’d include the UK public sector borrowing requirement (excluding financial institutions) because I imagined that the increased amount of debt might start pushing up British bond yields. Hah! Yesterday’s issue of GBP 3.75bn of 3-year gilts at an average rate of -0.003% shows there’s no problem funding the government yet.

Watch Marshall Gittler Market Preview video here: