I expect the meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to be pretty routine. I don’t expect much if any change in the statement following the meeting, except an upgrading of the economic outlook and an acknowledgment that the US vaccination program, which is proceeding ahead of schedule, has reduced the downside risks to the economy. Nonetheless central bankers are by nature a cautious lot and I don’t expect them to break out the verbal champagne just yet.

The important part will be the new Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), which has the economic and rate forecasts of the FOMC members. The updated forecasts will now take into account the passage of the Biden Administration’s $1.9tn fiscal support package as well as the faster-than-expected rollout of the vaccines. The growth forecasts should be revised substantially upwards. Many Fed officials have said recently that vaccination would lead to much stronger growth this year and that downside risks had abated. That may cause them to lower their unemployment forecasts and raise their inflation forecasts as well.

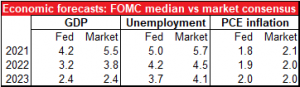

Comparing the December forecasts with today’s market forecasts, the market is more optimistic than the Fed was with regards to growth this year and next but more pessimistic with regards to unemployment.

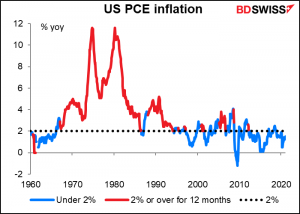

The market expects inflation to go back to the Fed’s 2% target level earlier than the Fed does, but remember that just going back to 2% is no longer enough to justify tightening. In its recently revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, the Fed said that “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time” (emphasis added). Since inflation as measured by the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, hasn’t been over 2% for one consecutive year for any sustained time since 2006, I think we would have to see higher forecasts than that to justify tightening.

I expect the Committee to remain unconcerned about inflationary pressures. Officials have noted that they are not concerned about a temporary rise in inflation this year driven by base effects or temporary bottlenecks, so long as underlying inflationary pressures remain subdued. Several of the regional Fed Presidents have said that they don’t expect the $1.9tn fiscal support package to cause the economy to overheat. Furthermore, many FOMC members have pointed out that when the unemployment rate got down to a 50-year low of 3.5% before the pandemic there was still no sign of overheating in the labor market.

On the other hand, Treasury Secretary Yellen has said that the Biden Administration’s recent fiscal support package could allow the labor market to recover to full employment by the end of next year. That’s significantly better than what the Fed forecast in December. We should pay particular attention to their employment forecast.

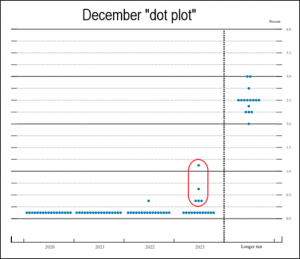

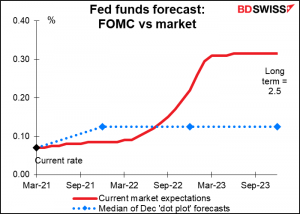

The big question is, what will happen with the “dot plot?” The Committee members’ forecasts for the end-year fed funds rate are likely to remain unchanged for this year and next, but what about 2023? Will they adjust their view in light of their (one assumes) improved economic forecasts?

In December, there were 12 dots at 0.125%, i.e. unchanged, three at 0.375% (i.e., one rate hike during the year), one at 0.625% (two hikes), and one optimist at a very aggressive 1.125% (probably also responsible for the one dot expecting a rate hike in 2022.)

If the median dot now expects a hike in 2023, that would have confirmed that once again, the Fed is moving toward the market’s view of things, rather than having the market come into line with the Fed’s way of thinking.

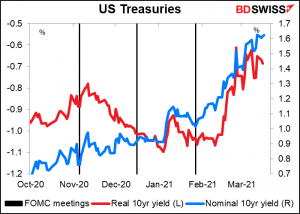

Aside from that, the important thing will be what they say about the recent rise in long-term rates and what if anything they plan to do about it. You can see from the graph how 10-year yields have risen since the last meeting in January – from 1.02% to 1.62%. This has not been due entirely to higher inflation expectations – on the contrary, real yields have risen alongside nominal yields. They could if they wanted to take several steps to deal with this problem, such as a) increase their bond purchases, b) “twist” them by buying less in the short end and more in the long end, or c) in the extreme, institute “yield curve control” (YCC) as Japan and Australia have done and set a target for the long end of the market.

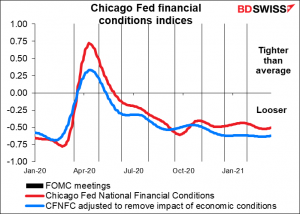

In the event, I doubt if they will do anything, and I expect Fed Chair Powell to remain sanguine on this point in his press conference. Looking at what Committee members have said recently, many indicated they are not concerned about higher yields since broader financial conditions remain accommodative. Several said that they would be concerned by a persistent tightening in broader financial conditions or disorderly market conditions, but we haven’t seen those yet. Quite the contrary – the Fed’s own gauge of financial conditions shows that they’re still looser than average.

I don’t expect any change in their view on asset purchase, either. Recent commentary from officials has emphasized that monetary policy will remain accommodative and that asset purchases will continue at least at their current pace for “some time.” Fed Presidents Daly and Bostic noted that they do not expect to begin tapering asset purchases this year, and Fed Presidents Bullard and George said it is too early to discuss tapering.

Market implications: An upgrading of economic forecasts together with a consensus on a rate hike in 2023 and no pushback against the market’s view on yields is likely to spark a further sell-off in bonds, in my view. I expect that would be likely to push stocks down and push USD up.

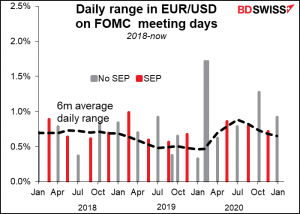

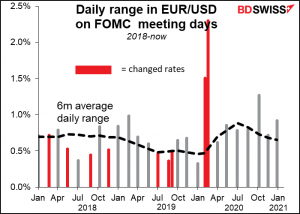

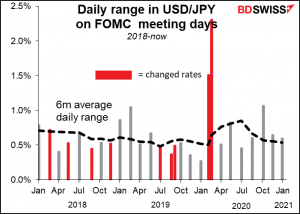

Last year, the market wasn’t unusually volatile on FOMC days when they didn’t move policy rates. Then again, a change in the “dot plot” estimate might be a different matter.

There doesn’t seem to be any pattern of unusual volatility on days when they publish the “dot plot.”