Rates as of 04:00 GMT

Market Recap

An amazing day! Basically, the Fed abolished free markets. It seized control of the last free corners of the US bond market, ending capital markets as we know them. To go through all the new steps it took would be far too detailed for this report; I suggest you read the financial press if you’re interested. (For background, Morgan Stanley has a background article on the act, called The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or CARES act. The article was written two days ago so does not include yesterday’s actions, but it covers the structure and aims.) The key points of yesterday’s $2.3tn news as far as I’m concerned are:

- It will ensure that credit flows to small- and mid-sized companies by offering to buy up to $600bn in loans to them. The loans will be for four years, with repayments deferred for one year. This should help to keep people in their jobs instead of just paying unemployment insurance to them. That will help to keep the economic structure intact so that there’s an economy remaining when all this is over.

- The Fed will buy municipal bonds. That’s a first for them. It reduces the need for investors to sort out which municipalities are worth investing in and which are risky.

- Most dramatically, in my view, the Fed said it would buy corporate debt that was investment grade as of 22 March but was subsequently downgraded –so-called “fallen angels.” This a truly radical move – it takes the “risk” part of “risk vs return” off the shoulders of investors.

- It’s also going to start buying some top-rated commercial mortgage-backed securities and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). Remember those? Albeit with big restrictions.

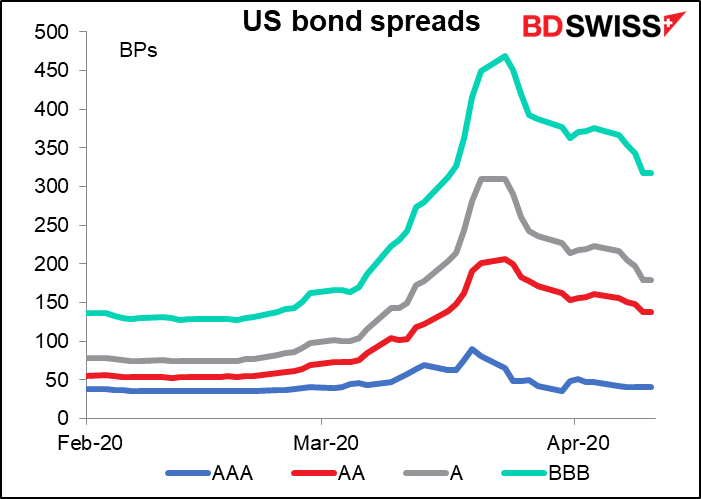

US corporate bond spreads came in as a result, as would be expected. They peaked on 23 March, two days before the CARES act passed Congress.

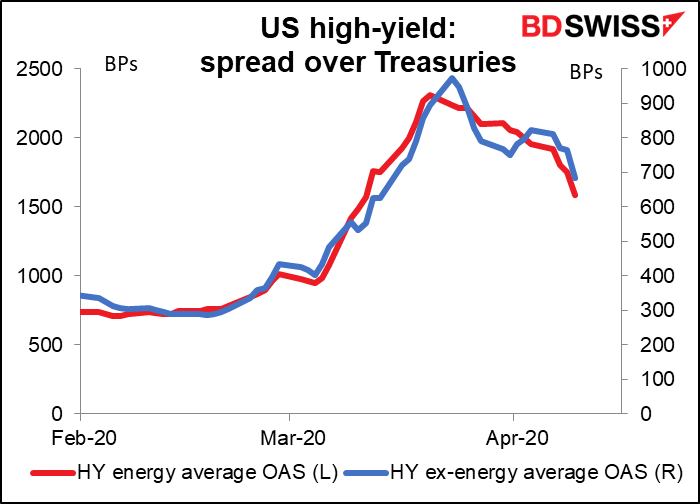

The impact was particularly strong in the high-yield world, as you can imagine:

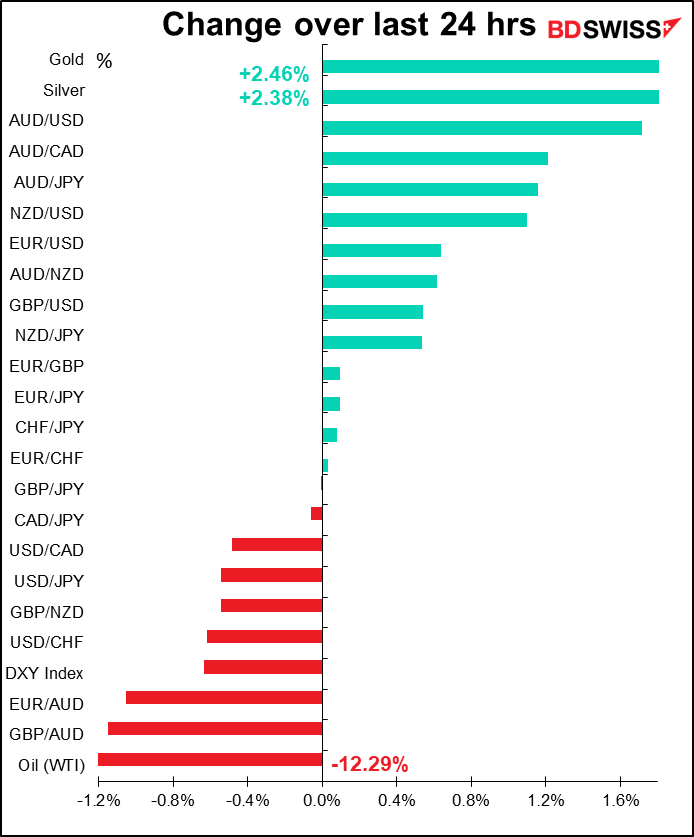

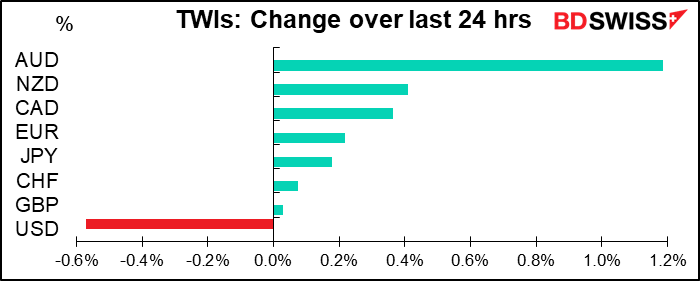

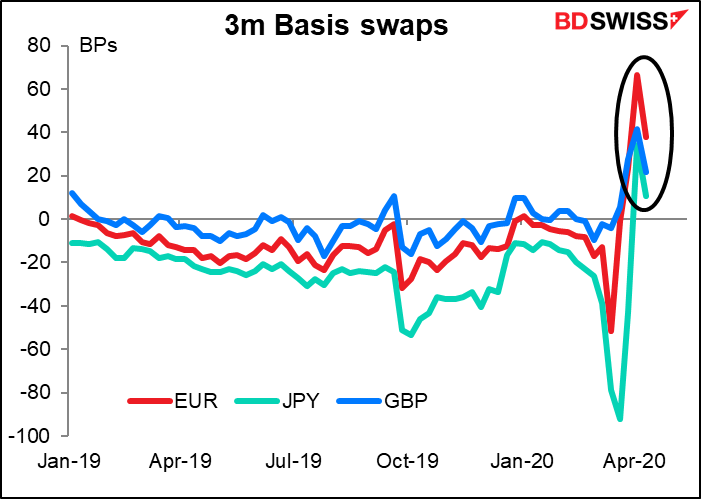

I think the willingness of the Fed to take on risk via junk bonds and municipal debt may be why the dollar eased on the news. Or perhaps it’s simply the size of what it’s doing – FX is a relative game, and if one central bank is expanding its balance sheet faster than others, the supply of that currency is going to expand faster than the supply of other currencies and ceteris paribus that currency should depreciate. Furthermore, the Fed’s earlier actions have kept the market awash with dollars, as shown by the fact that short-term currency basis swaps are still showing a premium for currencies, albeit a shrinking one.

Also, the small fact that 10% of the US workforce has filed for unemployment benefits in the last three weeks probably has impacted confidence in the currency. And as I mentioned yesterday, that’s just the tip of the iceberg, since so many people can’t get through to the government to file their claims.

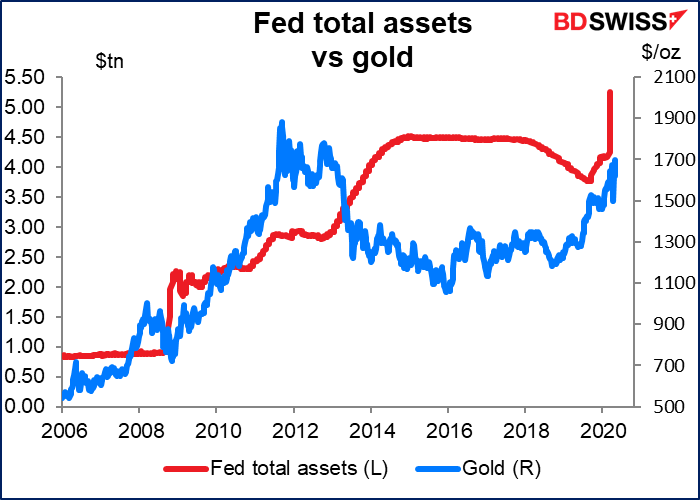

With the Fed going full out, gold hit a seven-year high as once again the market started to worry about currency debasement This is reminiscent of what happened in the market from 2008-2012, when so many people were sure that the Fed’s actions would result in Weimar-style hyperinflation.

Some people argue that the Fed moves are inevitable, because companies can’t be expected to prepare for a day when the economy simply stops – this is a unique period that requires a unique response. I say hogwash. Well, I say more than that, but not in a comment that’s going up on our website. The fact is that many Japanese companies are well prepared for such events by having large cash hoards. One company, Keyence, said it could survive 17 years without making a single sale. Since the Global Financial Crisis, US companies have spent trillions of dollars buying back their shares, with some 30% of the buybacks funded by issuing debt. What if instead they had spent trillions of dollars buying back their debt, with 30% funded by issuing new shares? The stock market wouldn’t be where it is, and management’s stock options might not be in the money, but the US taxpayer wouldn’t have to be bailing them out, either. It’s especially infuriating that the airlines have a special bailout program just for them, even though over the last decade they’ve spent 96% of their free cash flow on stock buybacks – from my experience, the remaining 4% went into refitting planes with more, smaller seats that don’t recline.

On the other side of the pond, Britain is the first major country to use monetary financing of the government – aka “Zimbabwe monetary policy” – to pay for the COVID-19 bills. The Bank of England acceded to the UK Treasury’s demand to grant the Treasury an unlimited overdraft– it will cash whatever cheques the Treasury cares to write for a limited period. That will allow the government to spend money without having to tap the gilts market.

In normal times this is the very definition of hyperinflationary economics, but in a situation like today, with a total collapse of demand, it’s sound policy, in my view. That’s because the government demand will make up for lost private-sector demand, not compete with it for resources. In 2008, the UK government spent about GBP 20bn in this way. Furthermore, if the government were to increase the issuance of gilts substantially, under current conditions – when most of the UK is running down its savings – it would have to find overseas buyers for these bonds. In order to entice overseas buyers, it would have to offer either higher interest rates – thus offsetting some of the benefits of the Bank of England’s easing – or a discount in the form of a cheaper pound – thereby risking imported inflation. The move should therefore also be seen as positive for the pound, as strange as that might seem.

OPEC+ finally reached agreement to cut output by 10mn b/d. Although this is by far the biggest reduction they’ve ever agreed on, oil prices fell on the news because a) it was by this point the bottom of the range of what was expected, and b) many of the details are still rather vague, most notably how it’s going to be enforced. Saudi Arabia and Russia agreed to cut by around 5mn b/d and other OPEC+ members agreed to cut a similar amount, although it’s not clear who will cut by how much and Mexico for one hasn’t signed on at all (Mexico is a member of OPEC+ but not OPEC). The group called on the US and Canada to cut by 5mn b/d when the G20 countries meet later today, an outcome that’s far from guaranteed. They may square the circle by having the G20 countries buy oil for their national petroleum reserves and count the increased demand as substituting for reduced supply. (See below for details)

EU officials finally reached a deal on a EUR 500bn virus response package that includes funding for the health care system, support for workers, loans for businesses, and a fund for a revival plan. The agreement is important because it indicates that there will indeed be a large-scale recovery program after the crisis is over to support the EU recovery. The news was positive for the euro.

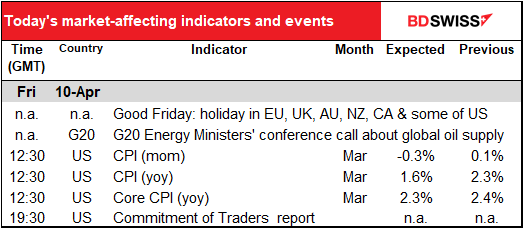

Today’s market

Lots of holidays around the world today. That could mean a quieter market than usual because of less news and fewer market participants, or it could mean a more volatile market than usual because of fewer market participants to take the opposite side of whatever trade becomes popular.

Following yesterday’s OPEC+ meeting, today what might be called OPEC++ meets. There will be a conference call of energy secretaries of the G20 countries. This is rather astonishing. Looking at the list of G20 countries, it has two OPEC members (Saudi Arabia and Indonesia), two OPEC+ member (Russia and Mexico), and four countries that are major producers but in neither group: US (12.1mn b/d), Canada (4.4mn b/d), China (3.8mn b/d), and Brazil (2.7mn b/d). (Australia, Argentina and India produce some oil but not globally significant amounts.) China is in a different situation than the others because its production is far less than it consumes and it imports over 10mn b/d on top of this – it’s in fact the world’s largest oil importer.

Why is the G20 getting involved? My guess is that it’s to provide the US with political cover for cooperating with OPEC. Price-fixing cartels are illegal under US law. Far from joining OPEC, many people have tried to sue OPEC for price-fixing in US courts, unsuccessfully so far. Starting in 2000, members of Congress have even introduced “NOPEC” bills that would help such suits to go forward, but so far these bills haven’t gotten anywhere either.

Accordingly, it would be unthinkable even for a recognized amoral traitor like…oh, sorry, for a Republican administration that at least pays lip service to capitalism to go along with OPEC or OPEC+ in fixing prices. However, “global policy coordination” is all the rage nowadays. A temporary exception could be made in the name of policy coordination.

Behind this is the fact that ever since it lifted the ban on exports in 2015, the US has become a major oil exporter. US exports averaged 3.5mn b/d in Q1. However, the transportation costs from Cushing, Oklahoma in the middle of the US to overseas markets are high relative to those of other countries whose oil is conveniently situated near the ocean. The benchmark Brent blend has to be $4/bbl more expensive than the US’ West Texas Intermediate (WTI) in order to make that trade economical. Since the OPEC+ talks failed in early March, that arbitrage has been negative for much of the time. The US needs to shore up prices so that it can continue to find overseas markets for its oil.

One way that they could shore up prices: instead of having the remaining G20 producers pledge cuts, they could have them pledge to increase demand. With oil so cheap now, it makes sense for governments to buy oil for the emergency storage facilities. The US and China could pledge to buy more for their Strategic Petroleum Reserves (in the US) or whatever the Chinese equivalent is, and count that in place of cuts.

Today’s indicators

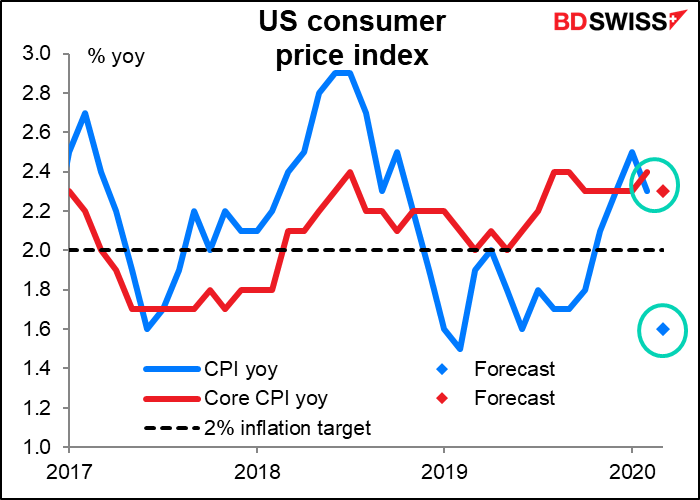

The only major indicator out today is the US consumer price index. Although it’s not the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, it’s still important in normal times because of its impact market views of inflation. But Fed policy is now going to be determined by the strength of the economy, and that’s going to be determined by the course of the virus.

In any case, the headline CPI is forecast to slow dramatically, probably because of plunging oil prices. But core inflation, which is what the Fed targets, is forecast to remain pretty much where it’s been since October. (In fact, core inflation has been between 2.0% – 2.4% yoy since March of 2018.) So it wouldn’t have much of an impact even in normal times, which these most certainly are not.