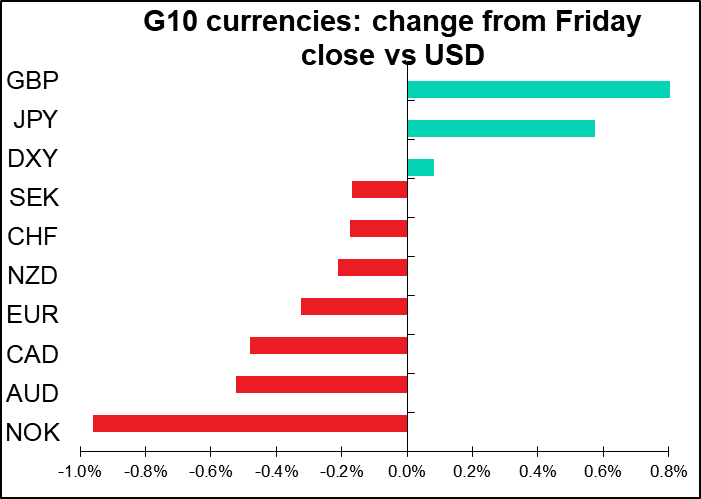

The week just ending saw three central bank meetings: the Bank of Japan, the Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank. What was noticeable about all three: they aren’t blowing the “all clear” whistle by any means. On the contrary, the BoJ and ECB were relatively unchanged, while the BoC turned distinctly bearish.

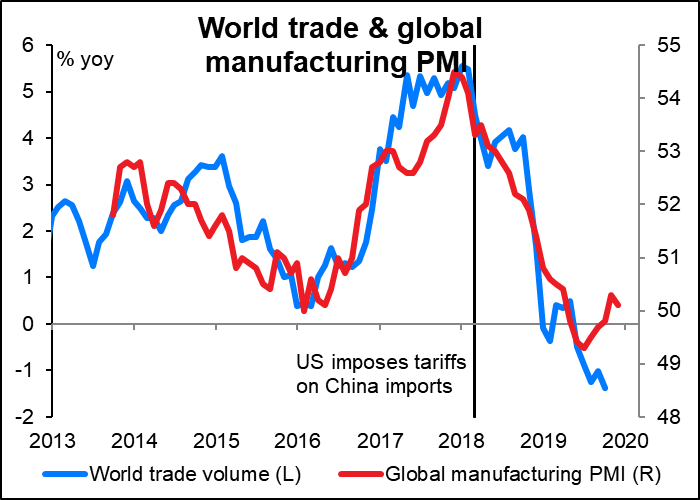

I had expected that the recent “Phase One” of the US-China trade agreement, for all its flaws and lacunae, would at least have given them a ray of hope. Nope. None of it.

The BoJ didn’t weigh in directly on the issue – which may be significant in and of itself – but did say that “With regard to the risk balance, risks to economic activity are skewed to the downside, particularly regarding developments in overseas economies.” So not much change their. Any optimism they had about trade was tied to the global IT cycle, not negotiations.

The BoC and the ECB made oblique references to the agreement, but were still far from assuming it would be successful. The ECB said that risks “have become less pronounced as some of the uncertainty surrounding international trade is receding.” The BoC, which should also have been pleased by the passage of the USMCA (the Agreement Formerly Known as NAFTA), didn’t refer to anything specifically, but just said that “some recent trade developments have been positive.” They hedged even this modest acknowledgement by saying that “there remains a high degree of uncertainty and geopolitical tensions have re-emerged,” no doubt a reference to the US-Iranian fighting.

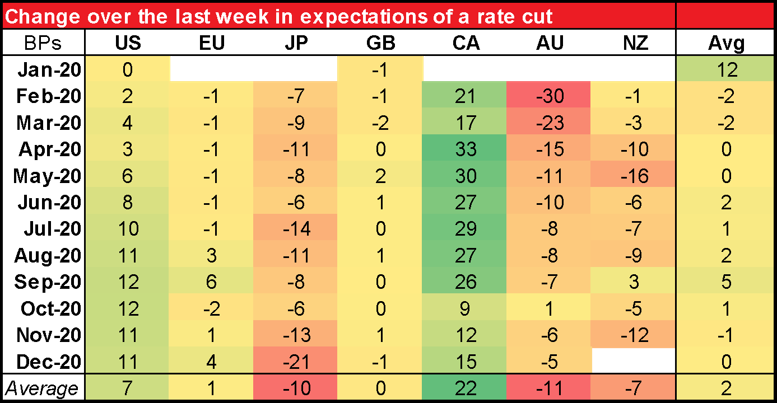

The odds of a rate cut in Japan did fall, probably because the BoJ upgraded its estimate for growth. (And besides, it’s difficult to envision the BoJ loosening any further unless they put Calixto Ortega Sánchez, the current Governor of the Bank of Venezuela, in charge of monetary policy.) But what stands out to me is the fact that while the odds of a rate cut in Canada went up sharply and up modestly in the US, the odds of a cut in Australia and New Zealand went down noticeably, especially in the early part of the year.

In the case of Australia, the change was clearly because of the better-than-expected employment data out on Thursday – the unemployment rate fell 1 tic lower to 5.1% with the participation rate unchanged, and employment grew almost 3x as much as was expected. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has made it quite clear that employment, not inflation, is its major policy goal right now. As long as they’re making progress towards that goal, there’s less need to change policy.

For New Zealand, an acceleration in inflation in Q4 to 1.9% yoy from 1.5% may have been the cause.

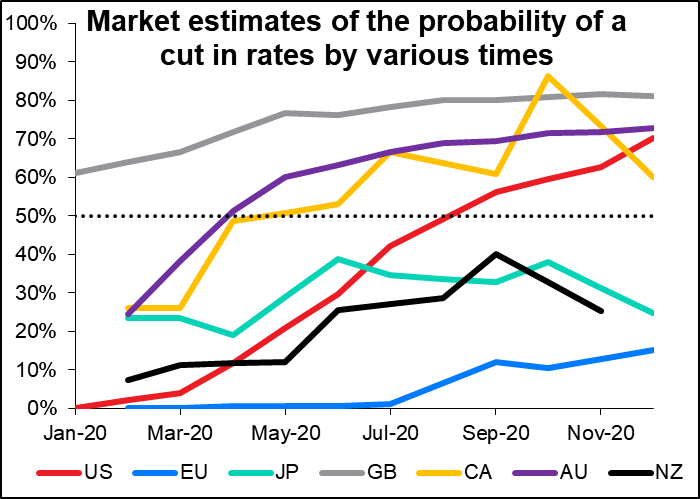

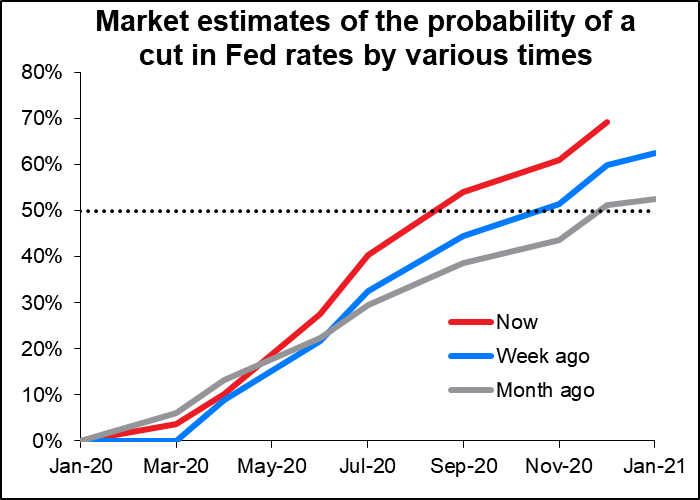

What I wonder is, which of these moves is correct? If the BoC is correct, then perhaps people are getting too optimistic about the RBA and RBNZ. If trade tensions really haven’t diminished, or aren’t going to diminish, then Australia and New Zealand will still be in trouble as so much of their exports go to with China (39% and 27%, respectively). On the other hand, if the antipodean moves are correct, then maybe the BoC is a bit too pessimistic about the outlook – and maybe the Fed isn’t as likely to cut rates as the market is currently thinking. (a 70% chance of a rate cut this year).

My view: I think the BoC is too pessimistic and they’ll change their tune before too long. I think “The Big Umbrella” Trump has shown he’s willing to fold in order to get an agreement done. I expect more and more concessions from the US in order to keep the talks on track and for the trade picture to improve further. The turnaround in the global manufacturing PMI recently suggests that the turning point isn’t too far away (we’ll know more about that later this afternoon, when the preliminary PMIs for January are released).

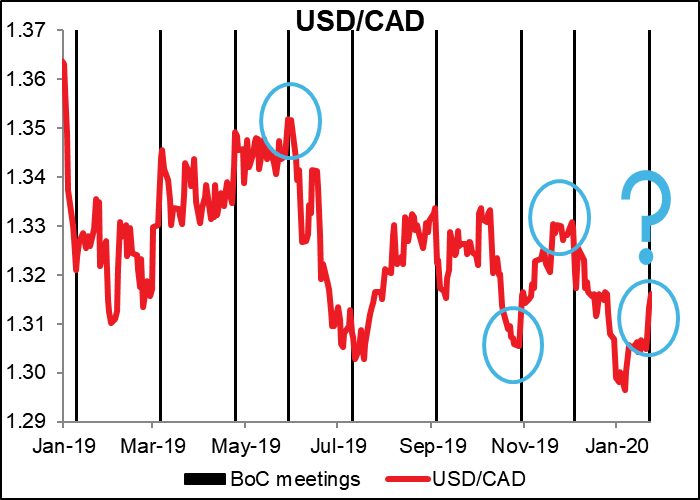

We’ve seen before how BoC meetings can result in lengthy trends for USD/CAD, lasting at least until the next BoC meeting. I think we may well have one of those scenarios now as well, so I wouldn’t necessarily fade the move at this point. But I think gradually the BoC – and the market – are likely to reassess their view and question whether they became more cautious just when it would actually have been more appropriate to become more optimistic. I still don’t expect any change in rates by BoC this year, or if they do, it’s more likely to be a rate hike, IMHO.

Of course the Fed is the key here and what they’re likely to do. The market view over the last week turned to be significantly more dovish, with more loosening priced in. And that brings us the schedule for next week.

Next week’s schedule: FOMC, Bank of England, US & EU Q4 GDP, and lots of inflation data

The meeting of the US Federal Reserve’s rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FMOC) and the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) are the highlights of the coming week. The US and the EU will both announce the first estimate of their Q4 GDP. And there will be lots of inflation data coming out, from Australia, Germany, Japan, EU and the US.

No one thinks the FOMC is going to decide to cut rates at this meeting. In fact, there’s a slightly higher risk priced in of them hiking rates, although that too is minor (12.3% vs 0%). But what is clear is that the market has gradually been raising the odds of a rate cut this year and bringing it forward. A month ago, there was only a 51% chance of a cut this year; now the market sees a 54% chance of a cut by September.

Personally, I don’t expect any major change in their stance or view at this meeting. Before they entered the blackout period – the two-week period before an FOMC meeting when Fed officials are forbidden from talking about monetary policy – the Committee members largely continued with the same consistent story that they’ve been putting forth for some time. They stuck to their view that policy is right where it should be and that any move in rates, up or down, would require a “material reassessment” of the economic outlook.

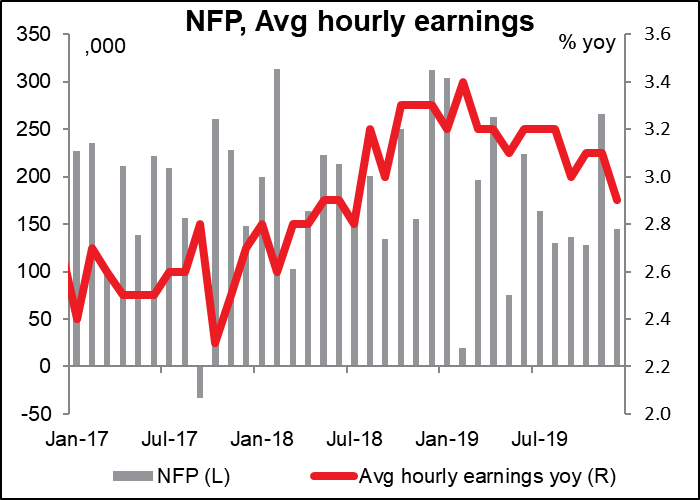

What information have we had since the 11 December FOMC meeting that might cause such a reassessment? With regards to the labor market, we had a modest nonfarm payroll figure, with the US adding only 145k jobs December, while average hourly earnings growth slowed and the number of job openings in the JOLTS report plunged. So the labor market side is still healthy, but starting to show some signs of weakening.

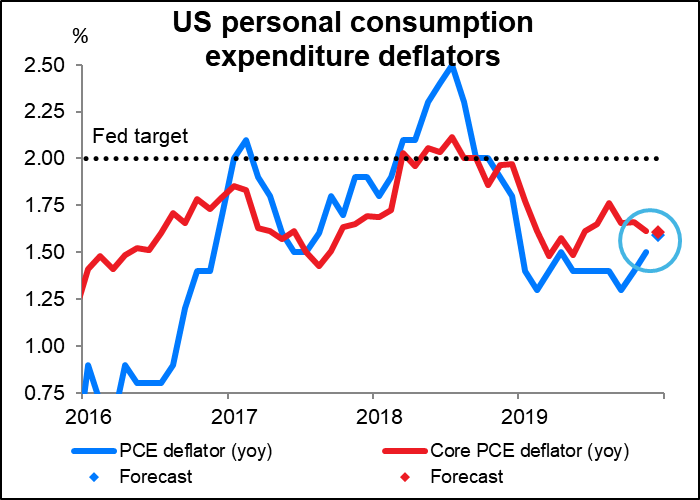

The inflation side also is presenting some problems. The December US consumer price index (CPI) showed inflation still running at a healthy 2.3% yoy, both at the headline and core measure. That’s above the Fed’s 2.0% target. But CPI isn’t the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. The Fed uses the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator. That’s actually been trending down recently. The difference comes from the different treatment of health care costs in the two measures (health care accounts for nearly 20% of the core PCE index, which tells you something about the crazy US health care system). Core PCE is forecast to end the year at +1.6% yoy, significantly below the Fed’s target, which is kind of surprising given that the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low and tariffs were imposed on a wide variety of goods.

Inflation expectations though are stable (5yr/5yr inflation swap) or trending upwards (5yr breakeven inflation rate), depending on which measure you use to value them. So the Fed probably isn’t worried (yet) that inflation expectations might become disanchored.

In other words, while there are some signs of potential problems on both parts of the Fed’s dual mandate, there’s nothing that would require a “material reassessment” of the economy. I don’t think the annual rotation of regional Fed presidents voting on the Committee will cause any major change in their stance. I think for the market to put a 50-50 probability on a rate cut by September is defensible, although a bit pessimistic. I expect the Committee to stick to their current view and I think the market will, too. USD neutral

With the Fed on hold, the Committee’s discussions and the press conference afterward will probably be dominated by questions about their balance sheet and the recent emergency measures they’ve been implementing to relieve the repo market. Have they launched a stealth QE? I’d expect reporters to press this issue but for Chair Powell to deny it up and down.

The Committee’s review of its monetary policy framework will also be discussed, but no conclusions are likely at this early stage.

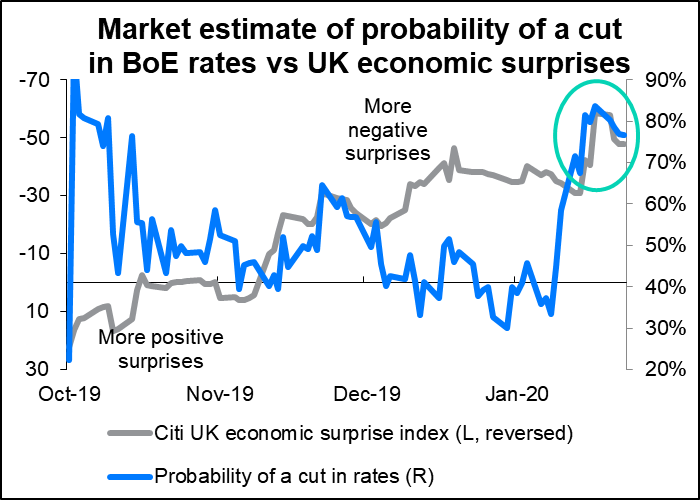

Thursday’s Bank of England MPC announcement presents more of a puzzle. You can see how the market’s conviction in a rate cut by September (blue line) had risen sharply, but then just as sharply started turning down in the last few days.

You can see the same pattern mirrored in the Citigroup economic indicator surprise index (grey line, below). The rise in rate cut expectations follows several disappointing economic indicators, particularly last Friday’s disastrous retail sales figures (-0.6% mom vs +0.6% mom expected). But then several other indicators came in better than expected, notably Tuesday’s employment data (employment +208k vs +110k expected) and Wednesday’s surge in the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) business optimism index (+23, vs -20 expected, -44 previous).The main point is that the retail sales figures were for December and the business optimism figure was for January, i.e. after the election. That gives more hope for the future.

BoE Gov. Carney recently divulged that there is a debate on the MPC “over the relative merits of near-term stimulus to reinforce the expected recovery in UK growth and inflation.” Two MPC members – Silvana Tenreyro and Gertjan Vlieghe – said earlier this month that they’d vote for cutting rates if there are no signs of improvement in the economy. This would be in addition to the two members (Jonathan Haskel and Michael Saunders) who said at the December meeting that they would like to see a cut in rates. Two + two = four = nearly half of the nine-member committee.

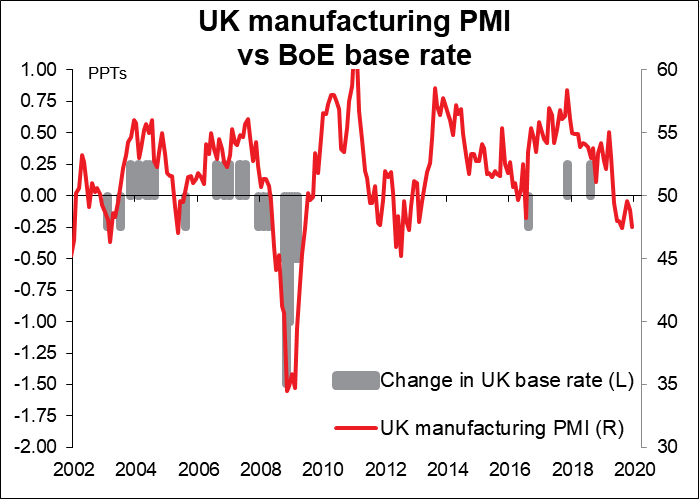

The question then is whether good employment data and a rise in business optimism outweigh terrible retail sales and slowing inflation. How many data points do they need to confirm an improvement? How long are they willing to wait? Today’s PMI will probably play a large role in that decision. You can see that the December level of the manufacturing PMI, 47.50, was quite at a level that has normally elicited a rate cut. (Since 2001, the Bank has cut 11 times when the PMI was below 50 and six times with it above or at 50. It didn’t cut in 2011-2013 when the PMI was below 50 because Bank Rate was already at a record-low 0.50%.)

Will they wait? I think the vote may be close this time – there could be three or four votes for cutting – but I think they won’t have a majority yet. The global picture is improving and we are on the cusp of Brexit. I think they will hold their fire and the pound is likely to rebound as a result.

Personally, I think they should wait until the March budget at least to see how the fiscal side will work out. I think governments have become entirely too reliant on monetary policy and need to use fiscal tools as well to manage their economies. Furthermore, it’s hard to make accurate forecasts about the economy without knowing what’s going to happen on the fiscal front. (It’s hard enough to make them even if you know.) But much can happen by then, especially with the UK leaving the EU on 31 January. They won’t wait if they do see further deterioration in the economy.

Other indicators: inflation, GDP

As I mentioned before, there will be a number of countries releasing their inflation data during the week.

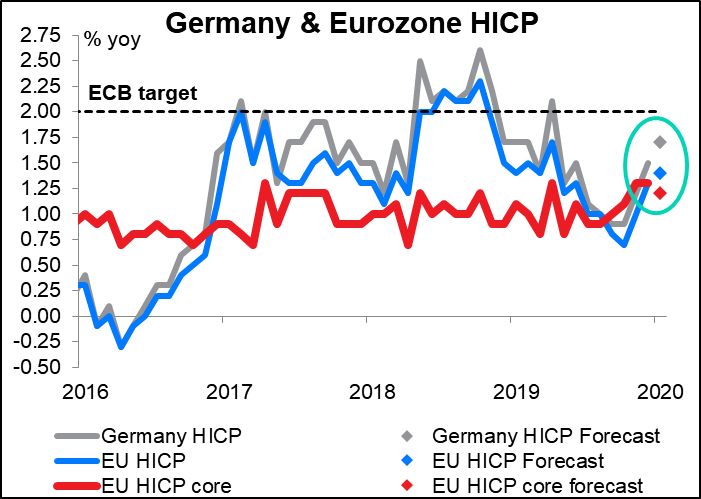

Germany’s harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) (Thursday) is expected to accelerate slightly to 1.7% yoy from 1.5%. The headline figure for the EU as a whole (Friday) is also expected to accelerate, albeit not as much. Alas, the core inflation rate for the EU as a whole is expected to slow slightly. That spells trouble for the ECB. At yesterday’s meeting, they said “While inflation developments remain subdued overall, there are some signs of a moderate increase in underlying inflation in line with expectations.” It’s kind of embarrassing that the next week, underlying inflation actually slows, no? Maybe not. Maybe they’re beyond being embarrassed by this kind of thing. In any event, it will make it harder for them to pretend that inflation is going back to their target level. EUR negative.

The Tokyo CPI (Friday morning) is likely to be as boring as usual. Although the Tokyo CPI is probably more important than the national CPI at this point, since it comes out so much earlier, in fact it never seems to fluctuate much and so doesn’t make many waves in the market. In this case, the headline figure is expected to be down a bit but the two core measures unchanged. Boring, boring, boring. JPY neutral.

Then Friday during the US day comes the biggie: the US personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators. As explained above, these are the gauges that the Fed uses as its definition of “inflation,” not the CPI. So in my view they should be the most important indicator every month, not the dreaded nonfarm payrolls, since right now an unemployment rate of 3.5% is far beyond fulfilling the Fed’s mandate of “maximum employment.” It’s the “stable prices” part that they have to worry about. In this case, the PCE deflator is expected to accelerate slightly, but the core PCE deflator – their most important inflation gauge – is forecast to remain at 1.6%. That’s well below their target and may be troubling. Not troubling enough for them to change their policy, but troubling enough to keep alive the possibility of a rate cut this year. USD neutral.

Finally, we have the first estimate of Q4 US and EU GDP.

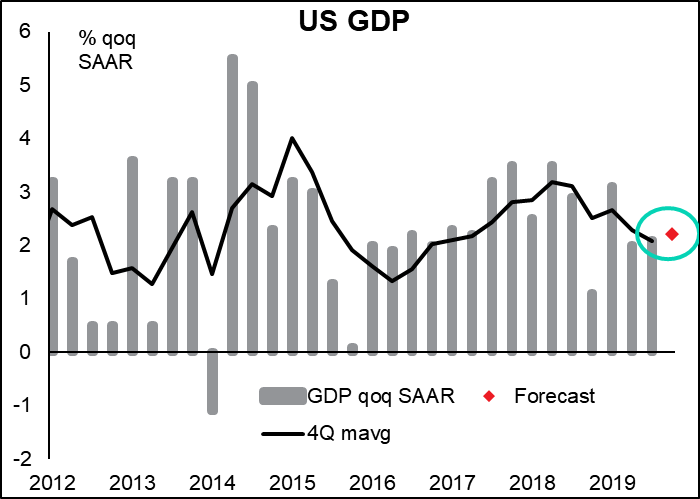

US Q4 GDP is expected to be up 2.2% qoq SAAR, which is slightly higher than in Q3 and slightly higher than the four-quarter moving average. Given the usual scale of revisions and the uncertainty that therefore surrounds the first estimate, we might as well say “unchanged.” That’s a pretty good result, given all that’s going on in the world. It would mean while the rest of the world has been going through a slowdown due to the trade friction, the US continues along at the same rate of growth as it has basically for the last year.

Note though that as usual, there’s a wide range of forecasts. The NY Fed estimates 1.2%; the Atlanta Fed estimates 1.8%; and the St. Louis Fed estimates 2.1%. Isn’t it amazing how people can look at the same numbers and come up with such different conclusions? In the Bloomberg survey, the range is from 1.5% to 2.9%. I think a figure towards the market median would be seen as reassuring for US growth and would tend to be positive for the dollar.

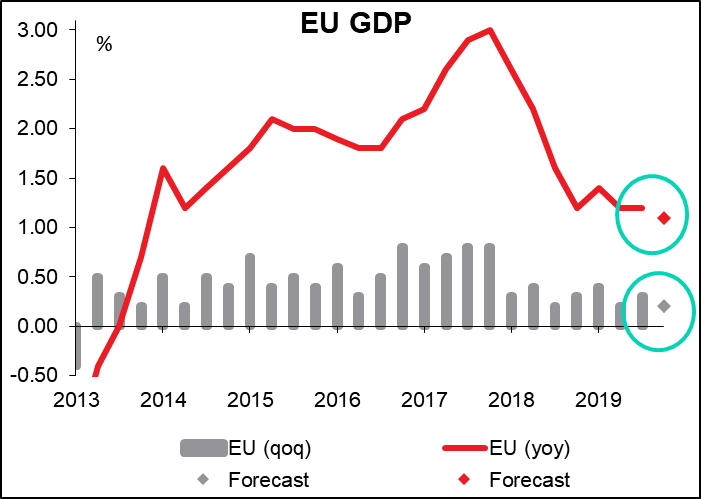

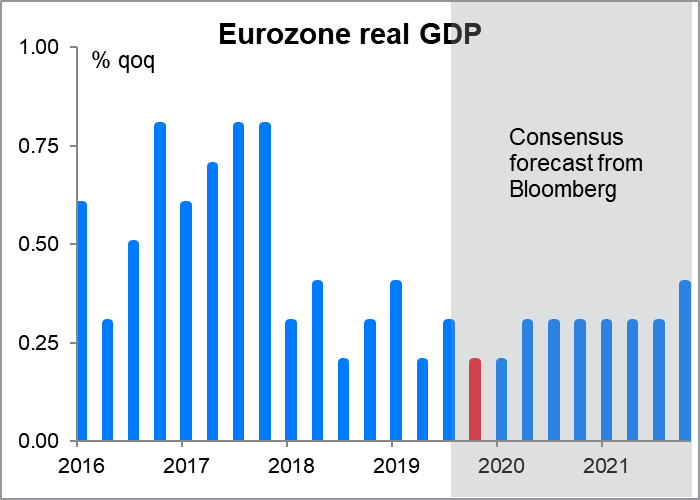

EU-wide Q4 GDP is forecast to grow at a slightly slower pace than in Q3, on both a qoq and yoy rate. While this isn’t good news, I don’t think it will come as a surprise, nor is it likely to disturb the market that much.

The prevailing view in the market is that Q4 was the trough and things are likely to get better from there. The market consensus is currently that growth bottoms out at 0.2% in Q4 2019 and Q1 2020 and then picks up from there. Accordingly, I think this is likely to be EUR neutral so long as it doesn’t slip below the consensus forecast.

Other important indicators out during the week include:

US: durable goods orders on Tuesday, the advance goods trade balance on Wednesday, and personal income & spending on Friday.

EU: Ifo survey Monday, money supply & bank lending on Wednesday, and German and EU-wide unemployment on Thursday.

Japan: the usual end-of-month data dump on Thursday, including employment data, industrial production and retail sales.