BDSwiss Special Market Analysis Coverage by Renowned Fundamental Analyst Marshall Gittler

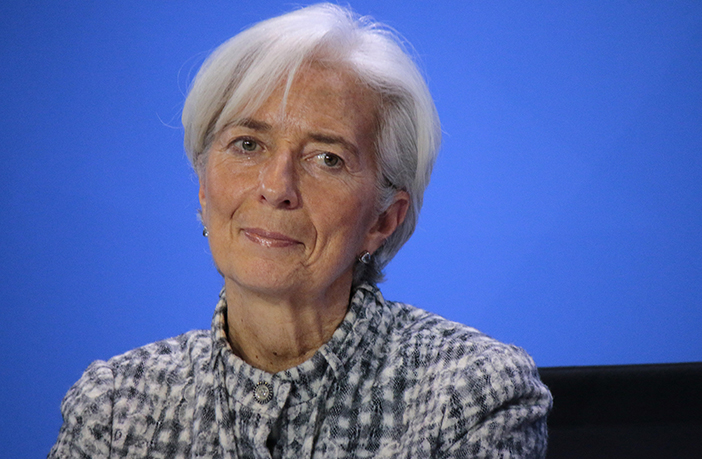

The EU surprised the market by appointing Christine Lagarde, the head of the IMF, to take the place of Mario Draghi when he retires as President of the ECB in November. She’s more of a politician than an economist, but that might be just what the ECB needs as this juncture as the ECB hits up against the limits of what monetary policy can do. On the other hand, her candidacy is likely to mean a somewhat weaker euro than would’ve been the case under a different ECB head.

First of, is Lagarde’s Appointment Even Legal? Article 283(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union says that the President shall be selected “from among persons of recognised standing and professional experience in monetary or banking matters…” Ms Lagarde is a lawyer by training and was the Finance Minister of France before becoming head of the IMF. She has no direct experience in monetary policy or for that matter in commercial or central banking – you can argue about whether the IMF is a bank (it does make loans, although not on commercial terms – neither does the ECB, for that matter). But I expect everyone to simply gloss over this question. She may not be a PhD economist like Draghi, but she’s not Ivanka Trump, either.

Her appointment is even more unusual given that the new #2 at the ECB, Luis de Guindos Jurado, has only a BA in economics and was also a politician – he was most recently the Economy Minister for Spain. But he was Economy Minister for Spain during the Eurozone’s financial crisis and managed the bailout of the country’s banks and overhaul of its banking sector, so that experience certainly qualified him.

The qualifications of these two contrast with the outgoing team –Draghi did his PhD in economics at MIT under some of the most famous economists in the world, while de Guindos’ predecessor, Vitor Constâncio, has an MA in economics and served twice as the Governor of the Banco de Portugal.

Having these two less-well-versed people at the top of the ECB board will shift a lot of the power to the new ECB Chief Economist, Philip Lane, who recently took over from Peter Praet. No one argues about Lane’s qualifications. He’s a PhD economist rated among the “Top 5% of Economists in the World” and the former Governor of the Bank of Ireland. Lagarde and de Guindos will probably rely on him for the more technical aspects of policy.

Lane made clear his views just this week in an extensive speech entitled “Monetary Policy and Below-Target Inflation.” He said:

In the context of the euro area, the ECB has been active and creative in deploying non-standard measures, in addition to extending the range for the policy rate into negative territory. Our assessment is that this policy package has been effective and further easing can be provided if required to deliver our mandate.

At the same time, an extended phase of below-target inflation poses a communication challenge in maintaining focus on the medium-term inflation goal…

This assessment suggests to me that, first off, Lane agrees with Draghi both on past ECB policy and the need to ease further. Thus we are likely to see ECB policy continue much as it has under Draghi, with an emphasis on getting inflation back up and supporting growth. And secondly, that Lane sees the need for a strong spokesperson for the Council who can explain ECB policy and win the support of the various constituents who are affected by it.

It looks to me like a well-thought-out team: a monetary expert to devise policy, and a seasoned politician to act as spokesperson and take the flack for the what’s bound to be the continued failure to meet their targets.

Furthermore, with the ECB approaching the limits of what monetary policy can do, much of its work from now on will be political rather than monetary: working towards a banking union and capital markets union and persuading EU politicians to do their part with structural reforms. Draghi’s statement after every ECB Council meeting ends with a plaintive cry for help from other parts of the EU governance machinery: “In order to reap the full benefits from our monetary policy measures, other policy areas must contribute more decisively to raising the longer-term growth potential and reducing vulnerabilities,” he says each time, but to what effect? Perhaps Lagarde won’t have the same authority as Draghi does when it comes to explaining the implications of M3 growth, but on the other hand, maybe her relations with the politicians will win her a hearing on other matters that he was less successful at.

Lagarde’s appointment is in some ways a return to the time when former Bank of France Gov. Jean-Claude Trichet was President (2003-2011). Although an economist by training, Trichet functioned largely as the spokesman for the Governing Council. Draghi, by contrast, has definitely led the group, often seeming to take bold decisions by himself – his “whatever it takes” statement of support for the euro was not the result of late-night haggling and compromise, like most EU decisions.

The ECB Governing Council may be shaping up to be more like the FOMC, which is also led by a lawyer nowadays – but obviously with a good number of economists and a large staff to present options and ideas. That comparison isn’t so reassuring though, considering that Fed Chair Powell has had some problems getting the hang of the communications side of his new job. And Powell had two advantages over Lagarde: he was on the FOMC for several years before taking over the top job, and the Fed’s policy is less complicated than the ECB’s, which has a bewildering array of programs with their accompanying acronyms (TLTRO, APP, NIRP, FG, etc).

The ECB will also lose one of its other main thinkers when Benoit Coeure leaves at the end of this year. Draghi, Coeure and the previous Chief Economist, Peter Praet, were the trio really running monetary policy. It’s not yet clear who will replace Coeure – if the person doesn’t have a strong monetary background, then basically it will be Peter Lane running the technical side of the show.

But in the final analysis, the euro is a political project, not an economic project, and it makes some sense to have someone who can handle the politics in charge of it.

What are Lagarde’s preferences? That’s the key for the euro. We don’t know for sure yet, but in April 2016 she said that negative interest rates in the Eurozone and Japan were “net positives” for the global economy. At the IMF she urged help for Greece and took the lead in apologizing for the IMF’s pushing of counter-productive austerity programs – showing she is more pro-growth than anti-inflation, and also that she is not doctrinaire. I would expect her to continue with the ECB’s search for new and creative ways to get inflation back up to their target of “below but close to 2%” – although the experience of Japan shows how hard it’s likely to be, absent structural reforms.

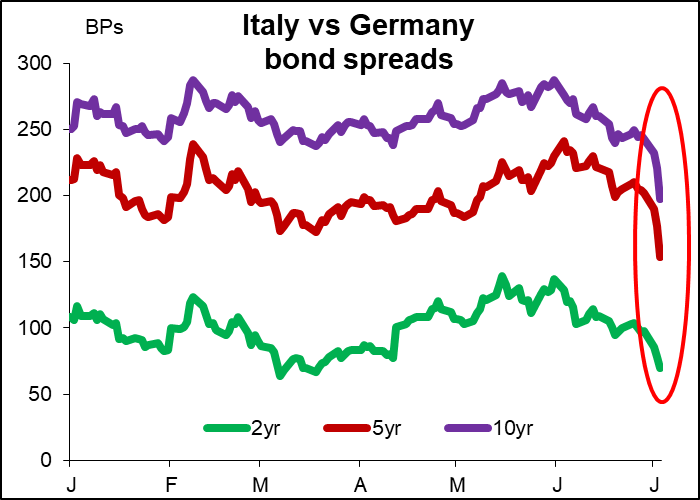

The market certainly expects her to continue in the vein that she was working at the IMF – the plunge in Italian bond yields today demonstrates that they consider her a “dove,” perhaps in contrast to the person who was thought to be the front-runner for the position, the uber-hawk Jens Weidmann. In that respect, I think her appointment should be seen as a small negative for the price of the euro, but a positive for its long-term future.