Trade disputes, Brexit, US poitics…it’s all disappeared. The market is now dominated by the novel coronavirus COVID-19 and its potential impact on the Chinese economy in the first instance and from there, the spillovers to the global economy.

So far, the view has been that it’s likely to be like the SARS virus in 2003 – a short, sharp shock that is over quickly with few if any lasting effects. The SARS virus, to refresh your memory, lasted from November 2002 to July 2003 and resulted in 774 deaths, mostly in China and Hong Kong. We’ve heard talk like this from several central banks recently:

- Reserve Bank of Australia (4 Feb): Another source of uncertainty is the coronavirus, which is having a significant effect on the Chinese economy at present. It is too early to determine how long-lasting the impact will be

- US Fed: (7 & 11 Feb): …possible spillovers from the effects of the coronavirus in China have presented a new risk to the outlook… we are closely monitoring the emergence of the coronavirus, which could lead to disruptions in China that spill over to the rest of the global economy.

- Reserve Bank of New Zealand (12 Feb): …the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak is an emerging downside risk. We assume the overall economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak in New Zealand will be of a short duration, with most of the impacts in the first half of 2020…There is a risk that the impact will be larger and more persistent.

- Riksbank: (12 Feb): The effects of the coronavirus are expected to reduce global growth in the short term, but it is difficult at present to fully assess the economic consequences.

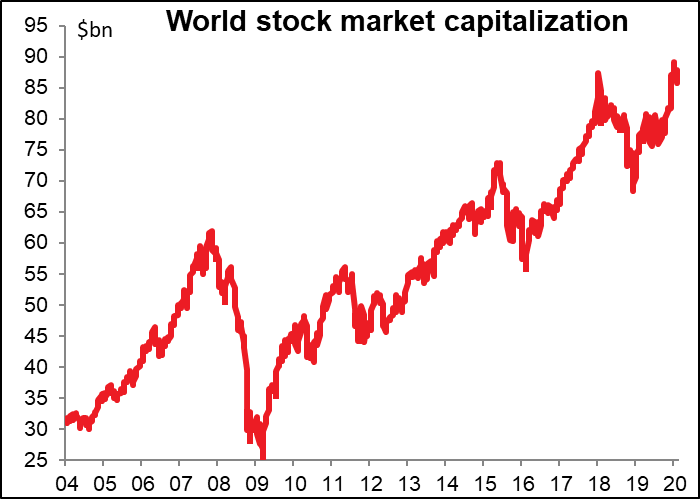

It’s clear that the market shares the central banks’ assumptions about the virus. Global stock markets are near a record high, which they probably would not be if people were expecting a re-run of the Spanish Flu of 1918.

Prices of some industrial commodities that are sensitive to Chinese economic activity have already started to recover, as are Shanghai stocks, indicating some optimism that the worst is over.

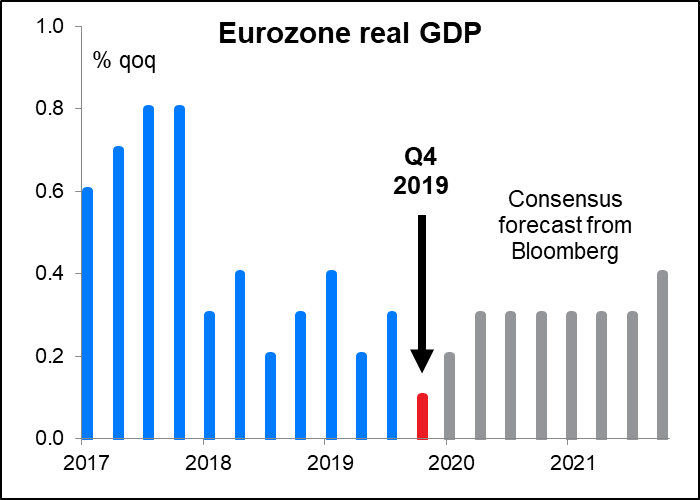

So far, economists’ forecasts are based on pretty much the same assumptions that the central banks are making. Looking at the forecasts for growth, particularly in the Eurozone, investors are assuming that Q4 was the trough and growth will rebound during 2020. That wouldn’t be the case if they were expecting a big, long-lasting hit to global demand.

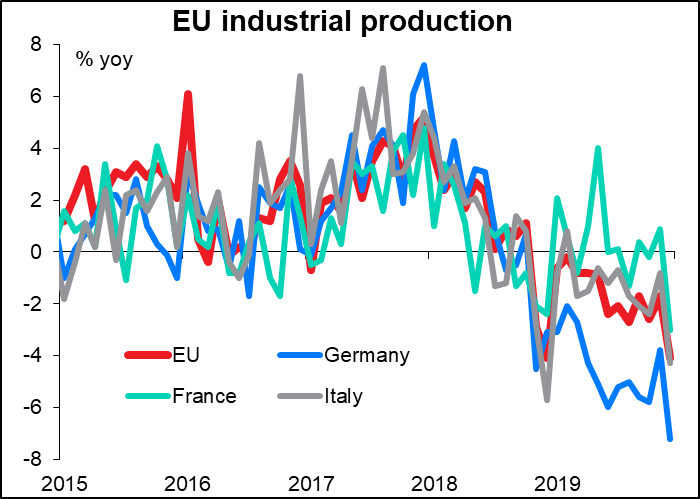

But recent news has called this rosy scenario into question, even before the coronavirus came on the scene. This week’s EU industrial production figures for December showed that if anything, the downturn was accelerating as 2019 ended.

In contrast, US growth accelerated slightly in Q4 and is expected to moderate somewhat in 2020.

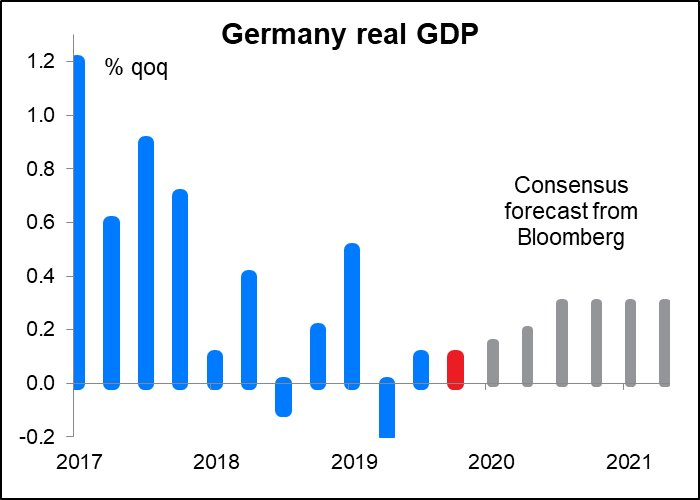

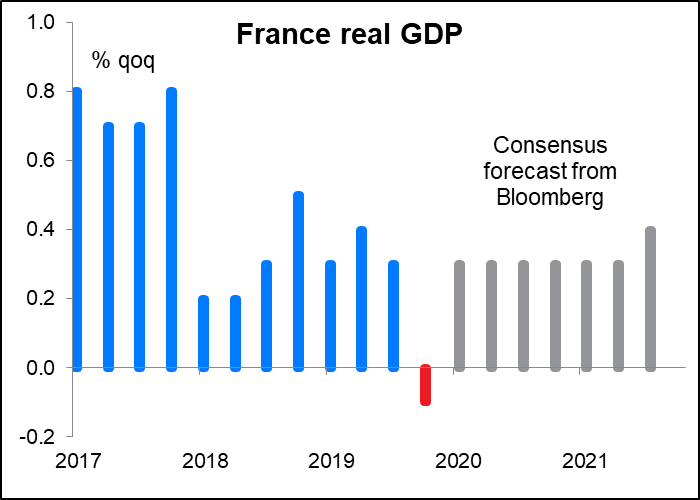

Recent indicators have shown this “economic performance divergence” – US outperformance and EU underpeformance — continuing. US indicators have increasingly been beating expectations, while EU indicators have been coming up below expectations. Even before the effect of the coronavirus spills over into global markets, it appears that investors may have to revise up their forecasts for US growth and revise down their forecasts for EU growth.

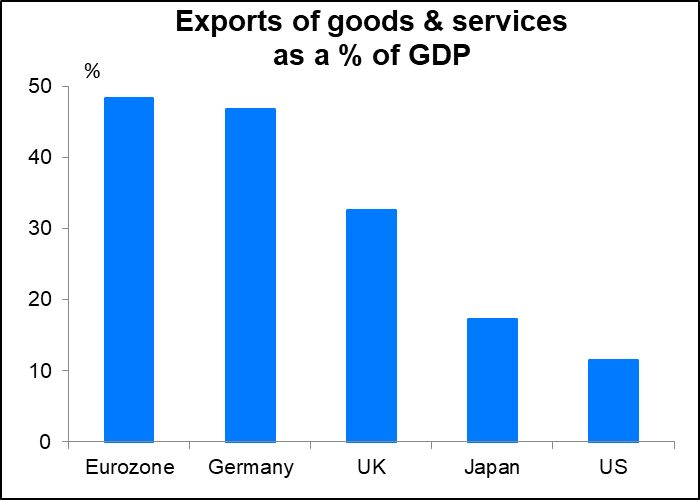

And that’s before the impact of the coronavirus, which is likely to dampen growth in China and, if it continues, growth worldwide as well. The impact of the virus will only increase the divergence between the EU and the US, because the EU is much more dependent on exports than the US is. To make matters worse for the EU, Germany’s significance in overall Eurozone growth is about double what its weight in the Eurozone economy is, which makes overall Eurozone growth more sensitive to exports than even these numbers would suggest.

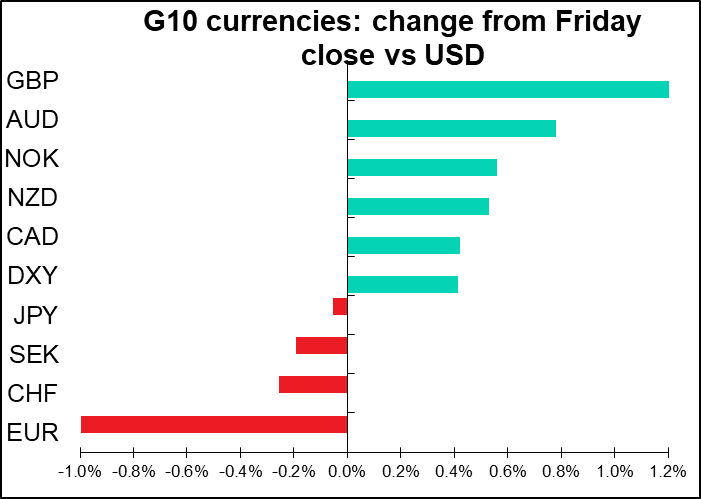

The relative growth in each region matters greatly for the currency market, because EUR/USD tends to track the expected difference in growth between the Eurozone and the US over time. If EU growth gets revised down relative to US growth,then it’s likely EUR will fall further relative to USD. In this respect, next Friday’s preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major economies will be extremely important to watch (see below).

As mentioned above, the markets and economists have been expecting the impact of the coronavirus to be over relatively quickly. One reason for these expectations was that the number of new cases appearing every day had peaked on 4 February. So while the epidemic was continuing, it looked like the worst was already over and China’s incredibly strict measures might have worked.

However, on Wednesday Hubei Province, the epicenter of the outbreak, revised its definition of people who are affected to include those who are “clinically diagnosed” with the virus. This change increased the number of confirmed cases by a staggering 14,890 people in one day. The market may now have to reconsider its views on the likely progress of the virus.

There are other reasons as well for the euro to weaken.

The political problems in Germany may also be weighing on the currency. German Chancellor Merkel’s heir apparent, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Monday resigned as the chair of Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party, leaving the leadership of the ruling coalition in Europe’s leading economy in disarray. The problem is not just who will succeed Merkel, but indeed whether the CDU/CDS coalition will even remain in power after the next federal elections, which are scheduled for September 2021 (but could be called earlier).

Furthermore, the euro’s use as a funding currency is depressing its value. More and more US companies are raising money in euros and moving it back to the US. This is in addition to speculators using EUR as a funding currency in carry trades.

I think these problems are likely to continue to weigh on the euro and the single currency may decline further over the next few months.

Next week’s indicators: preliminary PMIs, UK data

Of course the big thing that people will be looking out for next week is the daily virus victim count. Aside from that , there are no major central bank meetings and the data calendar is fairly light as well.

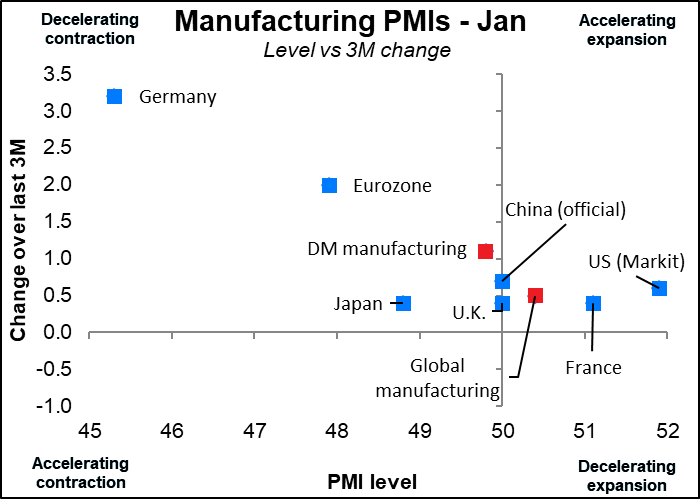

The major focus will be on Friday, when the preliminarly purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major economies (Japan, Eurozone, UK and US) for February are announced.

The market consensus forecasts were for the EU and US manufacturing PMIs to be lower (consensus forecast for UK is not yet available). (Service sector PMIs are expectedto be little changed.) This would be disappointing news, particularly for Europe, where manufacturing is already contracting.

Last month’s manufacturing PMIs showed a global economy teetering on the edge. The global manufacturing PMI is slightly in positive territory, while that for developed economies as a whole was slightly in contraction – no doubt because of the abysmal (but improving) figure from Germany. One good point: all the major countries in the graph below are above the line, that is, they’ve improved from three months ago even if they’re still contracting. The main point to watch out for this time is if any of them slip below the line to show either a decelerating expansion or, even worse, an accelerating contraction. Germany will remain the key one here as a) the biggest outlier, b) the worst performer, and c) the key to Eurozone performance.

In the US, the Empire State manufacturing index (Tuesday) and the Philadelphia Fed business sentiment index (Thursday) will give us a hint of what we might get from the PMIs and give us another up-to-date reading of the US economy. Other than that, not much out of the US: housing starts and producer prices on Wednesday and existing home sales on Friday are perhaps the major indicators.

The minutes of the latest FOMC meeting come out on Wednesday, but after two days of Humphrey-Hawkins testimony I’m not sure there’s much left to learn. It will probably be more important to listen to the many Fed speakers during the week: seven of the 17 FOMC members will be speaking, including five of the 10 voting members, especially on Friday, when there’s a seminar on “The Feedback Between Monetary Policy and Financial Markets” at the Booth School Forum. Many luminaries will be appearing there.

The minutes of the latest ECB meeting are out the next day, but we rarely get much enlightenment from them anyway. And in case you missed his appearance last week and his four speeches this week, the locquacious ECB Chief Economist Phillip Lane will be going to New York to speak yet again at the Booth School Forum.

There will be a number of important British indicators during the week: employment data on Tuesday, consumer prices on Wednesday, and retail sales on Thursday. All of them are important for the Bank of England’s thought process, although I expect that it’s the PMI that will be most important.

Inflation is only a concern insofar as it’s headed lower. It’s still within their “band of tolerance,” and the headline figure is expected to show some acceleration this month (no forecast for core inflation is available yet).

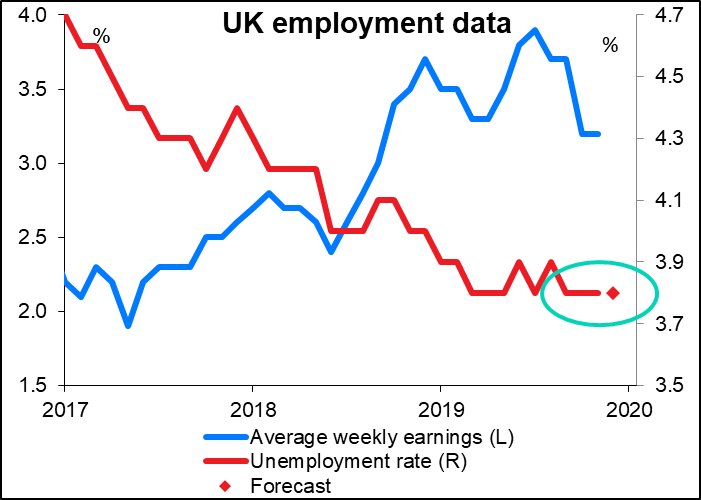

Given the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC)’s recent focus on growth and the overall health of the economy, rather than inflation per se, I think the employment data will be the most important of the three UK-specific numbers. It’s expected to show unemployment sticking at its recent level of 3.8%, where it’s been (more or less) since March last year. That shouldn’t be too exciting. (No forecasts available for other parts of the release yet.)

The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) industrial trends survey will be out on Thursday. Ordinarily this is a second- or even third-tier indicator that does not attract much attention, but last month it soared, setting off a brief rally in sterling in the expectation that the preliminary manufacturing PMI – which was released the following day – would also show a significant improvement. In the event the manufacturing PMI did not rise as much as the CBI survey indicated, but it did beat economists’ expectations. Coming a day before the PMIs, this survey may start to gain traction as an indicator of what the PMI are likely to show, much the way people look to the US ADP report to give a (misleading) hint of the US nonfarm payrolls.

Japan will release its nationwide CPI data on Friday morning Japan time. Who cares? Not only is the national CPI an anticlimax two weeks after the Tokyo CPI comes out, but in the larger scale, Japan hasn’t hit its inflation target in over 25 years, give or take a few months when a hike in the consumption tax temporarily pushed prices up. In fact, the main reason to watch the inflation data is to make sure that inflation isn’t decelerating again. The statement after every Bank of Japan meeting pledges that “the Bank will not hesitate to take additional easing measures if there is a greater possibility that the momentum toward achieving the price stability target will be lost.” Putting aside the question of whether there really is any such “momentum” (most unbiased observers would say no, not at all), if indeed it looks like deflation is returning, then they might be forced to put their money where their collective mouths are and “take additional easing measures,” whatever those might be.

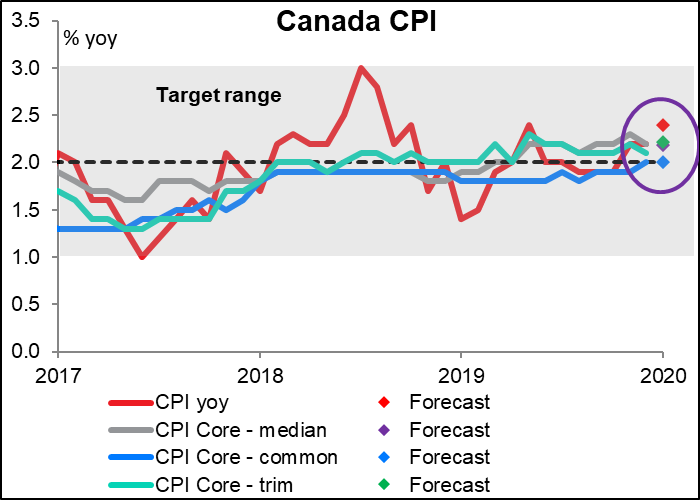

Canada will also release its inflation data, but there are few countries in the developed world where inflation is less of a concern than Canada, where all the measures of inflation are within ±20 bps of the central bank’s target. Like many other central banks, the Bank of Canada is more focused on growth right now than inflation. This is quite appropriate for the Bank, which sums up its mandate as “to promote the economic and financial welfare of Canadians.” Accordingly these figures should not have a major impact on CAD, but will be interesting to get a general view of the global inflation picture. The headline figure is expected to accelerate somewhat, but the BoC puts more weight on the various core measures, which are expected to show little change and therefore should not be significant for CAD.

Finally, Australia announces its employment data Thursday morning. This is perhaps the key data point for Australia, as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has made it clear that employment is its major concern nowadays. In the statement following its last several meetings, “the labour market” is the only “development” that they single out for monitoring. Curiously, the forecasts this month are exactly the same as the forecasts were last month – employment is expected to grow by 10k, which is only half the six-month average of 21k, and the unemployment rate is forecast to tick up slightly but to remain within its recent range. I think these developments might be seen as negative for AUD, except that probably any news about the coronavirus will take precedence over small changes in the domestic economy.

One other small point: the calendar is totally empty on Monday. It’s a holiday in Canada and the US and there are no major indicators out from anywhere else.