The year is drawing to a close, yet the drama continues unabated. There are still several stories moving the markets. Here’s a look at where we stand with the issues that got less attention than they deserved while the world anticipated the US elections but are now coming to the fore.

Virus pessimism vs vaccine optimism

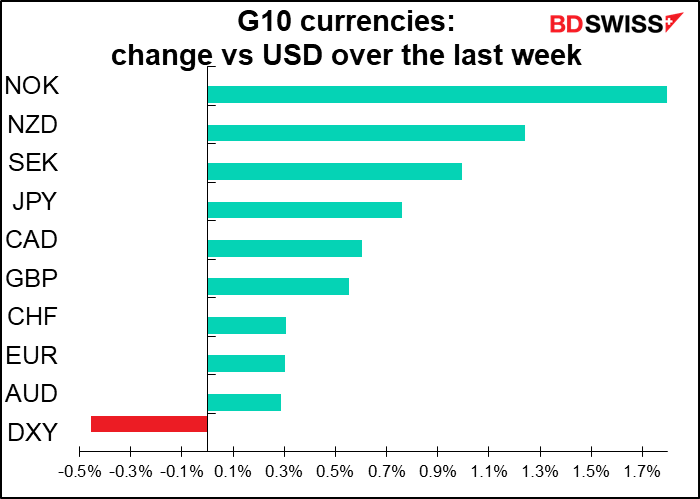

The number one international theme of course is the pandemic. The numbers continue to climb globally, with the US and Eurozone comprising an increasing percentage of global cases.

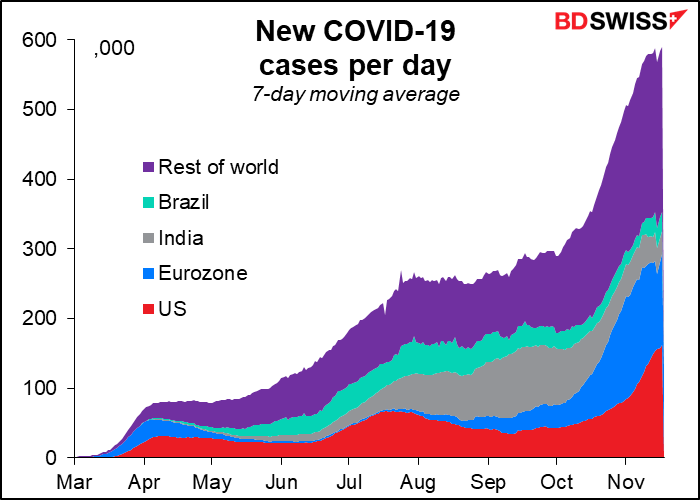

However, the financial markets – like many market participants in their personal lives – seem to have become accustomed to the virus as a fact of life. The Baker, Bloom & Davis Infectious Disease Equity Market Volatility Tracker, which tracks references to the virus in economic articles as a way of measuring its impact on market sentiment, suggests that it’s settled down to a fairly constant market factor.

There are occasional daily spikes when something big happens – a vaccine is announced, or Tokyo announces a record high number of cases, or New York shuts its schools – but these are no longer the unprecedented events that they were back in March and April.

We can still see on a day-to-day basis the tug-of-war between virus pessimism and vaccine optimism, but there are other important currents in the market as well.

Brexit: entering the endgame

The Brexit process seems to be drawing to a close. Finally! This is like one of those opera scenes where the heroine takes half an hour to die at the end, only this time it’s been four years. Some of us are starting to squirm in our seats and thinking about the drive home.

Ireland’s foreign minister, Simon Coveney, recently said. “We really are in the last week to 10 days of this. If there is not a breakthrough over the next week to 10 days then I think we really are in trouble and the focus will shift to preparing for a no-trade deal and all the disruption that that brings.”

The deadline for an agreement keeps moving away each time we approach it, like the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The UK had set 15 November as the deadline for an agreement. That would have left four weeks, which would be barely enough time to get everything ready so that the European Parliament could vote on it at its plenary session of 16 December. It’s estimated it would take six weeks for the deal to be translated, scrutinized and passed through committees in time for the European Parliament to vote in it. Now there are exactly six weeks left before B-day.

To make matters worse, the talks are now suspended as EU chief negotiator Barnier is quarantined as one member of his team caught the virus. That doesn’t make any difference to the schedule. Negotiations are suspended but the earth’s rotation isn’t.

The talk now is that with some creative thinking, the European Parliament could hold an extraordinary session on 28 December to vote on a partial agreement. This would require them to split the agreement in two, where one part falls entirely under EU law (“EU-only”) and the other involves areas of EU and member-state law (“mixed agreement,” such as aviation). The “EU-only” deal would not need to be ratified by national legislators, just European Council and European Parliament, and therefore could be approved quickly. Both treaties would end if the other wasn’t passed within a set period.

I still expect PM Boorish “The Big Umbrella” Johnson to fold, as he did on Northern Ireland, and for the two sides to reach an agreement largely on EU terms. The Financial Times recently unearthed a forgotten pamphlet written by UK Chief Negotiator Lord Frost just before the 2016 referendum in which he argued that “it will be Britain that has to make the concessions to get the deal.” This was written before he was the negotiator of course, but the logic remains the same: it “simply isn’t worth jeopardizing access to the single market for the sake of global trade.”

Furthermore, the stakes have risen with the election of the more EU-friendly Joe Biden as President. While Trump was happy to see the break-up of everything and the abrogation of any treaty, President-elect Biden has a different view. The Irish-American Biden (his mother’s side is entirely Irish) has made it clear that he expects Brexit to respect the Good Friday Agreement and international law in general. The US is Britain’s second-largest trading partner (11.7% of total trade, vs 49.2% for the EU). That argues for going along with the EU’s demands to make sure Britain doesn’t lose access to its second-biggest partner as well.

There’s also the integrity of the United Kingdom. Polls show that the Scots are anti-Brexit. There are elections for the Scottish Parliament in May. A “no-deal” Brexit could boost the popularity of the Scottish National Party, already the most popular party in Scotland, and amplify demands for independence. Ditto for Northern Ireland, which as it is may become more closely integrated into the Irish economy than the Great Britain economy. Who would want to be the Prime Minister who presided over the break-up of the UK?

Finally, doesn’t Britain have enough problems now? With the virus running out of control and the government heavily criticized for its management of the situation, PM Johnson needs a win. If he can work out some agreement I’m sure he can find some way to spin it as a win, whereas it’s hard to find a reason to celebrate a “no-deal” Brexit. This may be one reason why his hard-line advisor Dominic Cummings, the UK version of Steve Bannon, recently left the PM’s employ.

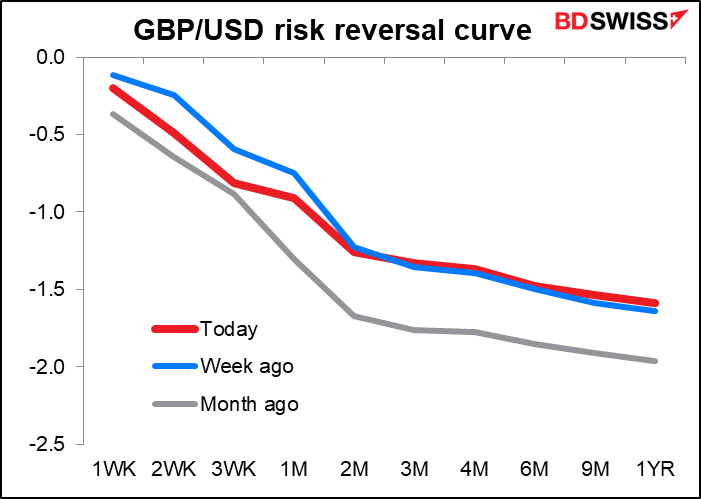

What would be the market impact of a Brexit deal? A recent Bloomberg survey of nine strategists concluded that a deal was largely priced in already. Its announcement would only send the pound up by around 2% to maybe $1.35. A no-deal Brexit could result in a slump to $1.25 however.

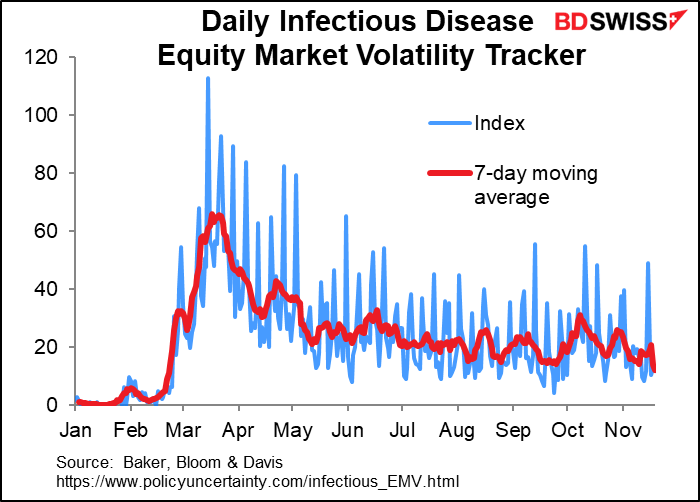

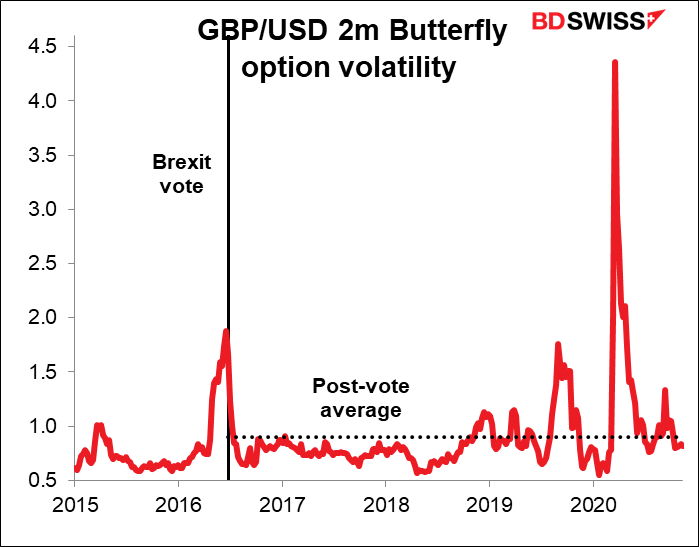

Looking at the sterling risk reversals, it’s clear that demand for insurance against a plunge in the pound has diminished over the last month.

Similarly, the two-month butterfly option volatility, a gauge of perceived likelihood of larger moves in the price of a currency over a given period, is currently slightly below its average since the referendum in 2016. This indicates that the market doesn’t expect an unusually large swing in either direction over the next two months.

I’m not convinced, however. I think whichever way it goes, we are likely to see a bigger move. There is still some uncertainty about whether they reach agreement, meaning we could have a bigger pop if it happens, whereas a “no-deal” Brexit, coupled with the inevitable chaos that I expect on 1 January (more about that at some later date), would probably send the pound lower.

Whichever it is though, the impact of the Brexit negotiations is likely to be diluted by the progress of the virus, which is turning out to be even more important for the UK economy in the near term.

EU: Recovery fund in jeopardy

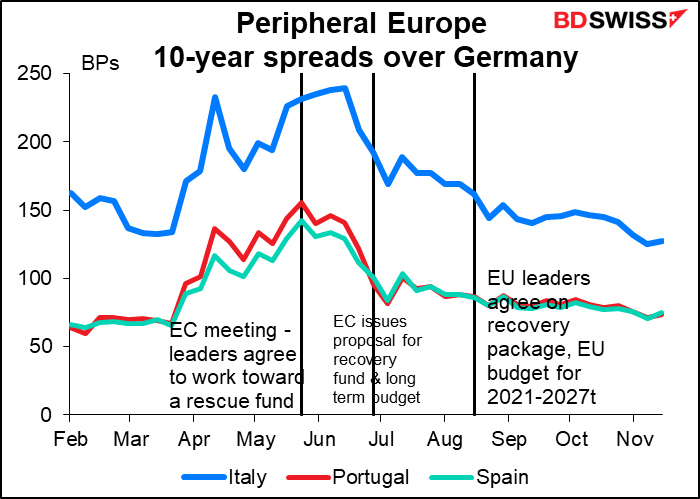

The financial world applauded back in July when the EU finally agreed on the EUR 750bn Recovery and Resilience Fund (RFF) to fund the economic consequences of the pandemic, plus the European budget for 2021-2027. The calming effects on the market were clear – peripheral bond spreads came in notably on this symbol of European solidarity.

Now however it’s all in danger from two angles.

First off, European finance ministers haven’t yet agreed on the technical details of the fund and are running out of time to get this done before the end of the year and the supposed start of the new budget.

Secondly, the whole construct is coming under attack. The European Parliament (EP) and European Commission (EC) combined the multi-year budget framework with the “rule-of-law” mechanism. This mechanism would allow the bloc to deny funds to countries that violate democratic norms, such as “endangering the independence of the judiciary” or “failing to prevent…arbitrary or unlawful decisions by public authorities,” etc.

However, the countries that this mechanism is aimed at – Poland and Hungary, in the first instance — object at what they see as infringements of their sovereignty. They have threatened to veto the entire package, which requires the unanimous approval of all 27 countries. It’s a game of chicken in that while Poland and Hungary benefit significantly from the EU budget, they’re well aware that other countries – Spain and Italy in particular – stand to gain from the Recovery and Resilience Fund. Also net contributors to the budget will not get their recently negotiated “rebates” on contributions to the budget.

The group made no progress on this debate at Thursday’s conference and pushed it off to the next European Council summit meeting on 10 December.

How will this end? The long-standing custom in the EU is to reach a compromise five minutes before the deadline. It is also possible that the “package” will be separated into its three constituent parts and they will go ahead with only those members that agree to the rule-of-law mechanism, although Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte called that “the nuclear options.”

If worse comes to worst and they fail to break the deadlock by the end of the year, the bloc will continue to function but with limited resources. The bloc can spend at most one-twelfth of the previous financial year’s budget every month.

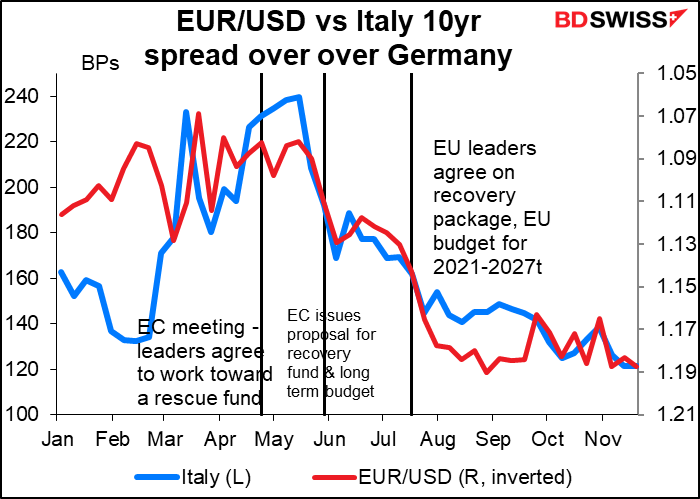

Impact on the euro: The decision to launch a big rescue fund for the Eurozone by means of joint liability bonds was a sea change for the euro, for two reasons. One, it was a symbol that the fiscal authorities as well as the monetary authorities were willing to do “whatever it takes” to keep the Eurozone together. Secondly, bringing in the fiscal authorities meant that the monetary authorities would not have to bear the entire burden of supporting the Eurozone economy.

As the graph shows, the decline in peripheral bond spreads, the market’s expression of increased confidence in the Eurozone following the decision, was matched by a rally in the euro itself. Any indications that the agreement might unravel could cause the tightening in peripheral spreads and the rally in the euro to unravel, too.

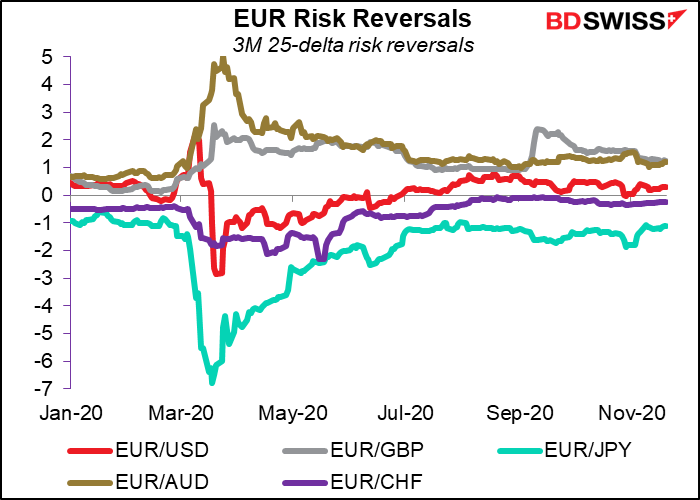

The market is not particularly worried about this problem at the moment. EUR risk reversals haven’t moved significantly over the last few weeks. That’s because EUR/USD has been stuck in this 1.16-1.19 range since July.

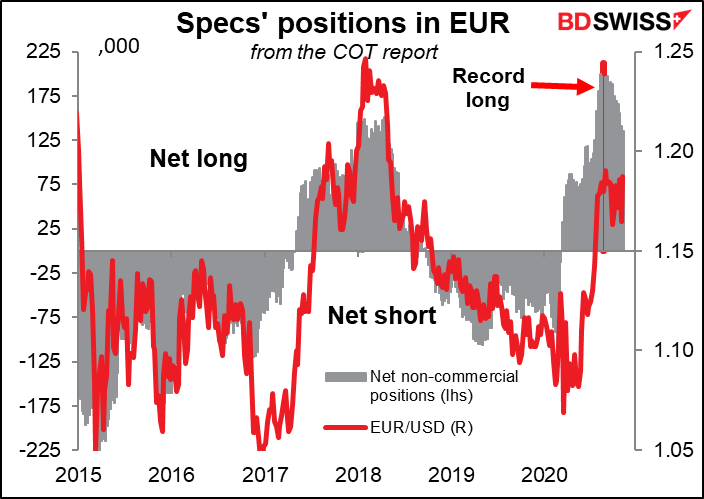

While speculators remain long EUR, they’ve been cutting their positions since hitting a record long back in August. They still have plenty more that they can sell if they start to get worried.

US election: lost but not over

Face it – Trump lost. His myrmidons appear on TV spouting the most outrageous conspiracies you can imagine and some you can’t (involving Hugo Chavez, who died in 2013, and servers in Germany – I can’t even follow it) but that’s just for TV consumption. In court they produce no evidence and are getting thrown out. So far they’re 1-29 in court cases.

He hasn’t given up yet, though. He reportedly invited Michigan’s Senate majority leader and Speaker of the House to the White House on Friday. Both are Republicans who have said that whoever has the most votes in Michigan after the results are certified will get the state’s 16 electoral votes. Why would he want to see them in person except to get them to throw out the results and have the state legislature select its own slate of electors? Former Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said Trump was trying “to subvert the will of the people and overturn the election.” “It is difficult to imagine a worse, more undemocratic act by a sitting American President,” he added.

President-elect Biden’s lead is too big in too many states for this strategy to succeed (we hope). It has however succeeded in planting doubts in the minds of Trump’s supporters. Half of all Republicans apparently believe that Trump rightfully won the election. (I wonder what the intersection is between that set of people and the 26% of Americans who believe the sun revolves around the earth?)

Former President Obama said, “If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false… the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition our democracy doesn’t work.” That’s where we are today.

Why are they doing this, then? This fantasy may help Trump in his reported bid for a second term in 2024, or some other Trump wanna-be running on a platform like his. It will also help the Republicans to justify resistance to any and all programs that the Democrats try to implement, as they can argue that that the Biden Administration is illegitimate. This is a long-term negative for US growth and a negative for the dollar. It remains to be seen how the new administration plans to overcome this obstacle.

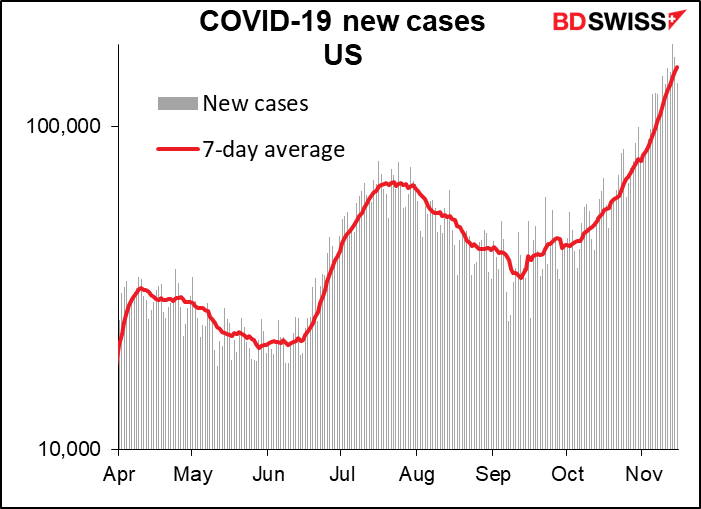

The more immediate danger for the US is next week’s Thanksgiving holiday. This is usually the biggest travel day of the year for the US as people tend to gather with family and friends for a big meal. Plans have changed this year because of the virus, but still, some 50.6mn people are expected to travel for Thanksgiving this year, according to the AAA (formerly known as the American Automobile Association). Although down from 56mn last year, it’s still a lot more than the 5mn people who left Wuhan for the Chinese New Year before travel restrictions were imposed, setting off the global pandemic. We could see a further spike in virus infections by Christmas as a result.

The upward curve in the red line in this logarithmic graph shows that not only is the virus spreading exponentially in the US, but at an accelerating exponential pace.

To make matters worse, out of those people still alive some 12mn are set to lose their unemployment benefits on 26 December when funding for the two main CARES Act programs, the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) and Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) programs, expires. That’s on top of an estimated 4.4mn workers who will have already exhausted their CARES Act benefits before this cutoff. All of these workers will start 2021 with little or no aid available to them. The US economy faces a fiscal cliff just at the same time as Britain will be leaping off into the unknown.

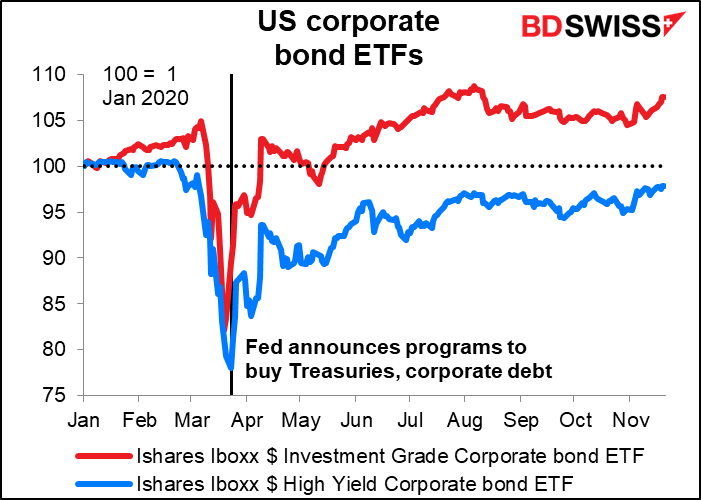

To make matters even worser, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin Thursday asked the Fed to return unused funds from five emergency programs ahead of their expiration in late December. This would force the Fed to shut down its Main Street Lending, Muni Lending, and Corporate Credit programs. At the same time, Mnuchin did ask the Fed to extend for 90 days four emergency credit facilities that backstop short-term funding markets, including commercial paper and money market mutual funds. In other words, he wants to end the programs helping small businesses and state & local governments while extending the programs designed to protect Wall Street. Unusually, the Fed openly disagreed, saying the programs serve as “a backstop for our still-strained and vulnerable economy.”

Why is Mnuchin doing this? Probably it’s part of the Trump regime’s “scorched earth” policy. They are trying to screw up the US economy as badly as possible before leaving so that the incoming Biden administration has a difficult time getting the economy back on an even keel. Then the Republicans can take over the House of Representatives in the 2022 election, and Bob’s your uncle! As they say in Britain.

The end of the Corporate Credit program could cause corporate bond spreads to widen, which might have a knock-on effect on the stock market, risk appetite, and thereby to the FX market. As the graph shows, the announcement on 23 March of the Fed’s programs to buy bonds marked the wides for corporate bond spreads.

With the Eurozone headed for a fiscal crisis and the US headed for a medical and fiscal crisis, the two crises could cancel each other out and leave EUR/USD little changed. Then again, one or the other currency could break out. I think the euro is in more trouble short-term (next month or so) but the dollar is in more trouble over the medium term (two or three months, or longer).

Next week: enough is enough

Usually I go through the next week’s indicators in some depth and detail in this weekly column. However at some point I think enough is enough and you must be tired of reading this. So I’ll just hit a few highlights this week and deal with the others as they come out next week.

There are no major central bank meetings and few speakers on the schedule. The US is likely to be quiet ahead of the Thanksgiving holiday Thursday. As it’s a holiday on Thursday, many people usually take Friday off too. Japan has a holiday on Monday.

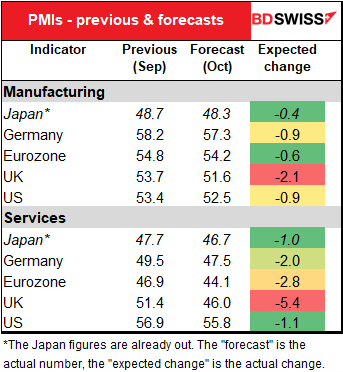

The main data of the week will be the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major industrial countries on Monday. They’re expected to be bad; all of them that we have forecasts for are expected to be lower, particularly the UK. That was the experience of Japan, whose figures came out Friday as they are on holiday Monday.

UK services are forecast to fall back below the 50 “boom or bust” line, which is particularly disappointing. The US is also expected to fall, nowhere near as much as the Eurozone. Furthermore the US service-sector PMI is expected to remain so far above 50 that it could prove a positive for the dollar.

The big day of the week will be Wednesday. Is this a plot by the government to keep traders in their offices and prevent them from going anywhere for Thanksgiving? On Wednesday, the day before Thanksgiving, the US will announce:

- Advance goods trade balance

- 3rd estimate of Q3 GDP

- Durable goods orders

- Personal income & Spending

- Personal consumption expenditure deflators

- New home sales

- Release of November FOMC meeting minutes

Besides of course the weekly indicators:

- MBA mortgage applications

- Jobless claims (moved due to the holiday)

- DoE US crude oil inventories

Elsewhere, the Ifo survey comes out on Tuesday and the Tokyo CPI on Friday.

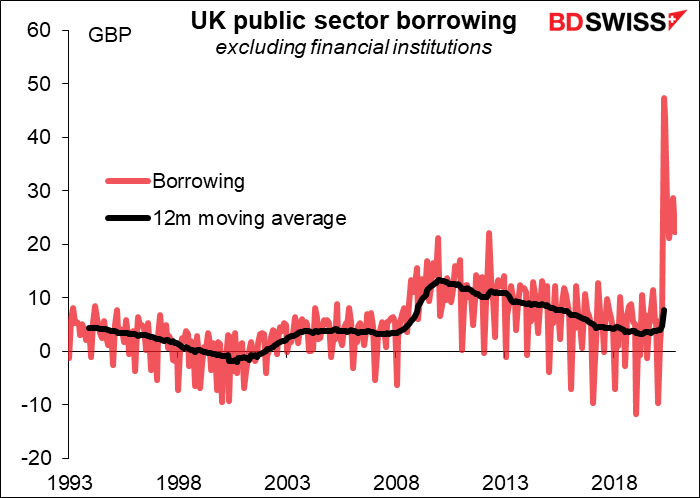

Finally, in addition to the Brexit negotiations, Britain will face Chancellor of the Exchequer Sunak’s annual Spending Review. Press reports are that he’s going to put the squeeze on public sector pay, except for health care workers, to hold down spending.

I’m not convinced of the need to hold down spending when the gilts yield curve is negative out to five years. The government can actually make a little money by borrowing & spending now.

However with borrowing soaring to unprecedented peacetime levels (as it has everywhere) many governments, including the UK, are starting to get a bit concerned, even though tax revenues in the UK have held up better than expected and the deficit is not as wide as was previously feared.

Joke of the day:

Interviewer: So, I see there is a four-year gap in your resume`. Did you work in the Trump Administration?

Candidate: No, Sir. I was in prison. I swear.