Rates as of 04:00 GMT

Market Recap

A “risk-off” wave emanating from stock markets swept the FX market yesterday.

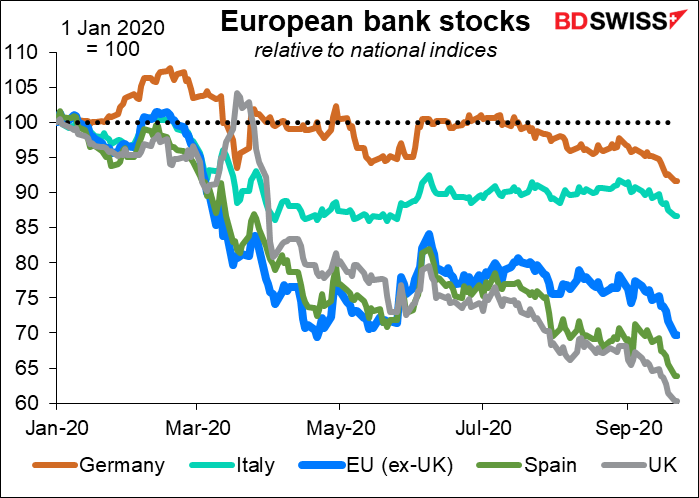

Although the Asian day started fairly solid yesterday, markets quickly moved south as the European day began. Equity markets in Europe plunged over 3%, the most in three months. Financials led the decline on a report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) into money-laundering by major banks. Bank stocks have been much weaker than the markets overall for most of this year despite the lending backstop from central banks.

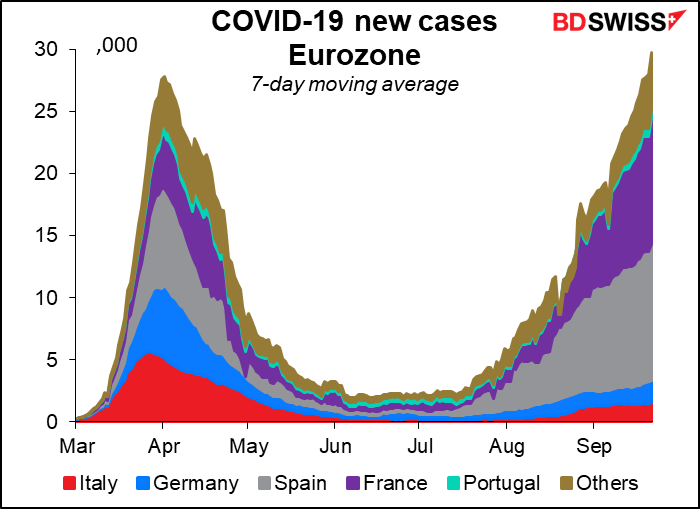

Worries about the second wave of virus cases in the EU – now exceeding the size of the first wave – exacerbated the declines. There’s a lot of concern that Europe will have to go back into lockdown, particularly in Britain. I doubt if the European public will tolerate it again, but there may well be more restrictive measures – Britain announced a new closing time of 10 PM for pubs, whatever that’s supposed to accomplish.

The problems in Europe certainly are matched by problems in the US, where the death of Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg adds a whole new level of acrimony to an already pitched election season. On top of everything else that’s going on, the US government is going to run out of money in nine days and the two sides can’t agree on a stopgap funding bill that would keep the government going through 11 December.

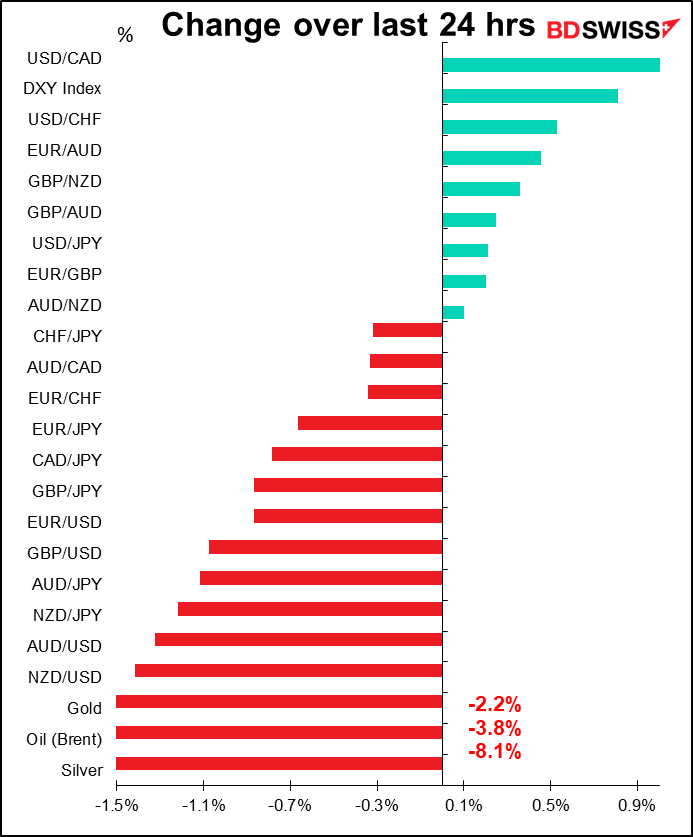

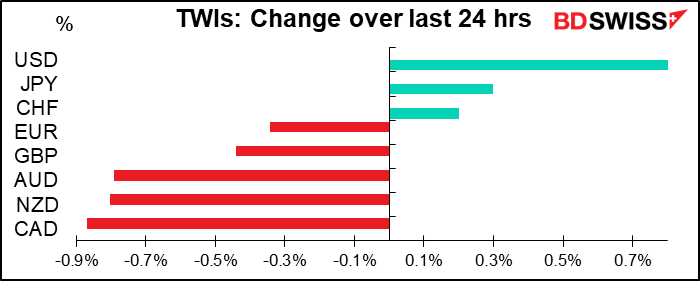

The reaction in the FX market to the risk-off environment was what one might expect, with JPY and CHF rising and the commodity currencies falling, especially CAD and NOK (not shown), which were pulled down by the drop in oil prices. Note though that USD was the best-performing currency as the “international dollar” retained its place as the safest of the safe-havens. That may also be because some of the strength in JPY – reflected selling of EUR/JPY – may be spilling over into EUR/USD as well.

Commodities were generally weak, with oil and gold both falling. Gold briefly fell below $1,900. Silver really tanked! Down over 8%.

ECB President Lagarde spoke yesterday. She basically repeated her usual spiel. I noticed that once again she mentioned the exchange rate: “the uncertainty of the current environment requires a very careful assessment of the incoming information, including developments in the exchange rate, with regard to its implications for the medium-term inflation outlook.” (emphasis added) This line about “developments in the exchange rate” has been cropping up a lot recently in Executive Council members’ speeches. I’m sure that’s no accident. They’re driving home a message.

The Bundesbank reinforced that point yesterday with a statistical study, The influence of monetary policy on the Exchange rate of the euro. The report (available only in German, unfortunately) apparently concludes that monetary policy does influence the exchange rate – hardly a novel idea, I’d say. According to Google Translate, the report says, “The monetary policy of central banks is an important factor influencing the exchange rate. True, exchange rates are not a target of Eurosystem monetary policy, but monetary policy does so significantly co-determined interest rate environment centrally for the exchange rate development of the euro.” I think more than the conclusion, which was never in doubt, the timing of the report may be significant. Why publish it now?

It’s clear that the ECB wants people to know that it’s concerned about the exchange rate, even if I don’t sympathize at all (it’s still undervalued vs USD). The question for me is, what can they do to influence it? They want the market to believe that they will loosen monetary policy further if the exchange rate rises too far. However, I think the marginal impact from further loosening of monetary policy in the EU would be quite low.

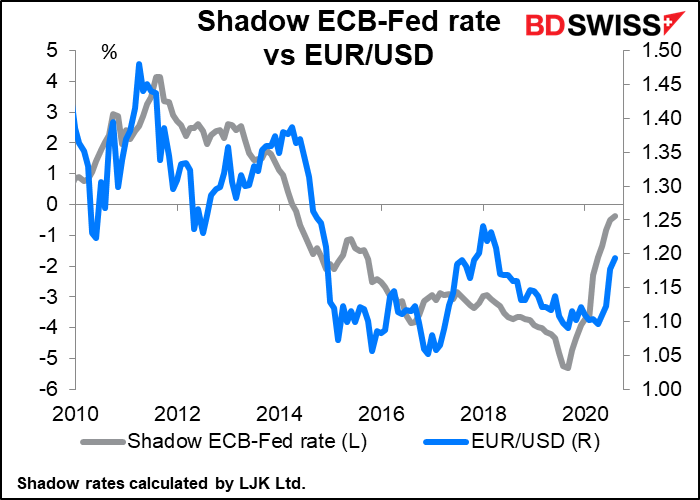

The problem is, the ECB just simply doesn’t have that much more room to loosen policy when compared with other central banks. Notice the huge decline in the “shadow” policy rate* of the Fed over the last two years vs the rather stable ECB shadow rate this year. The ECB shadow rate has previously been some 130 bps lower than it is today, which suggests that they do have more room to loosen policy – and thereby influence the rate – but without a change in the ECB’s single mandate, would that be more convincing to the market than what the Fed is doing?

(*”shadow” rates are the central bank’s policy rate adjusted to take into account the effect of quantitative easing and other extraordinary policy measures to give an effective gauge of a central bank’s overall policy stance when rates are constrained at the effective lower bound.)

The relative shadow rate between the ECB and the Fed does indeed seem to influence EUR/USD. I just question how much more the ECB can move it relative to the room that the Fed still has. One plus for the ECB: the Fed has ruled out negative interest rates, in part because of the huge amount of money market funds in the US, while the ECB retains the option to push rates even further into negative territory.

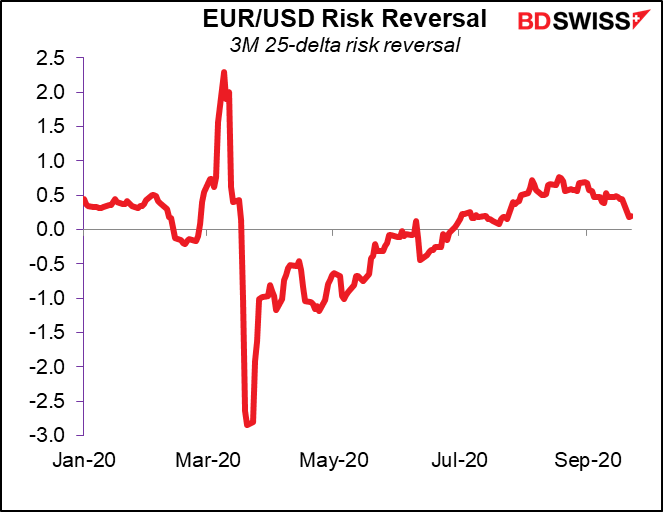

In any case, the jawboning seems to have worked; the ECB does seems to have been successful in changing market psychology. EUR/USD is no longer seen as a sure thing. In addition to the reduction in long EUR positioning that I mentioned yesterday, there has been increasing demand for EUR downside protection in the options market, as reflected in a lower risk reversal rate.

Dallas Fed President Kaplan appeared on Bloomberg TV and clarified why he dissented from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) statement last week. Kaplan said in his dissent that he would prefer to retain “greater policy-rate flexibility” than commit to allowing inflation to exceed 2%. “I would rather leave those judgments to future committees because I think the world is going to look very different post-pandemic than it does now,” he explained. Promising to leave rates low even as inflation exceeds 2% is in effect promising negative real interest rates, which can encourage further risk-taking. “My concern is about building up excess risk taking, which can create fragilities and other excesses in the system,” Kaplan said. “It could create issues for us to meet our goals. I felt that the costs were not worth the benefits.”

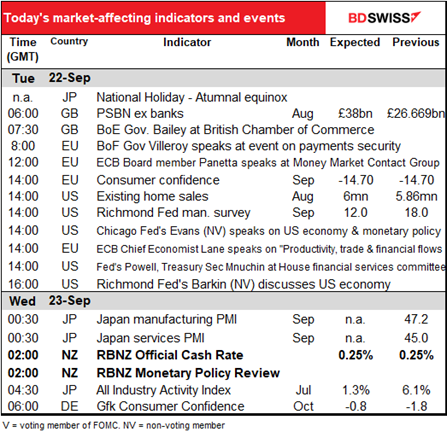

Today’s market

Once again, the day looks set to be more talk than numbers. Lots of ECB and Fed speakers, including Fed Chair Powell and US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin testifying at the House Financial Services Committee about the CARES act. Powell’s initial comments are already available on the Fed’s website. Looking quickly over the statement, he doesn’t break any new ground. Mostly he covers the Fed’s various lending programs and gives an update on how they’re performing. (It’s noticeable that even in this discussion, he mentions the lopsided impact the virus has had on minority workers – this is a new theme for the Fed and makes me think once again that they now have an employment target more than an inflation target.)

If you miss Powell’s comments, don’t worry – you’ll get a chance to hear him again tomorrow when he appears before the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, and then again on Thursday, when he (and Mnuchin) testify before the Senate Banking Committee on the CARES Act again.

Mnuchin’s comments are likely to be posted here. If past performance is any guide, his introductory comments will probably be even less illuminating than Powell’s. I doubt if they will vary much from what he said when he testified to the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on 1 Sep. His profound comments then included such revelations as “While we continue to see signs of a strong economic recovery, we are sensitive to the fact that there is more work to be done, and certain areas of the economy require additional relief.”

The one area in which their testimony could be market-moving centers on the Fed’s emergency 13(3) credit facilities. These facilities, originally created during the 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis, now help support the corporate bond, commercial paper, municipal bond and nonresidential asset-backed security markets. Some Senate Republicans want to take money that’s been allocated to these facilities but not spent yet and reallocate it to other areas, which would probably cause a “risk-off” mood in US credit markets. I expect both gentlemen to push back against this idea and emphasize the importance of maintaining these facilities, some of which are expected to stop operating by the end of the year anyway. Powell’s introductory statement covers these facilities in some detail.

I think Bank of England Gov. Bailey will probably be the most interesting speaker of the day. He’ll be talking on a British Chamber of Commerce webinar. “Discussions will focus on the Bank’s monetary policy decision to significantly expand quantitative easing, how it works with financial institutions to ensure that measures taken translate into on the ground support for businesses, and what further steps will be needed to ensure a fiscal environment that limits economic scarring and helps kickstart a recovery.” After last week’s surprise news that the Bank is beginning “structured engagement on the operational considerations” for implementing negative interest rates, he’ll probably want to take the opportunity to clarify the Bank’s intentions.

ECB Chief Economist Lane will chair a panel discussion at the ECB/CompNet online event on “Productivity, trade and financial flows in the face of a pandemic: a European perspective.” I wonder if he’ll sneak in a mention of the exchange rate into the discussion of trade and financial flows. It’s possible. That could be a market-mover.

Overnight, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) meets. I discussed this at some length in this week’s Weekly Outlook. In short, I don’t expect the RBNZ to announce anything notable at this meeting. Back in March they pledged to keep the OCR at its current level “for at least 12 months,” so this is not a difficult call.

Moreover, Finance Minister Grant Robertson Friday cast doubt on whether the RBNZ would need to change policy at all once the one-year freeze is over. In an interview with Bloomberg Television, he said the NZ economy is rebounding from recession and looking robust, etc. etc., and that the RBNZ “will bear all of that in mind when they come to think about their decisions post-March next year.” Hint, hint. I doubt if the meeting will be particularly market-affecting.

Today’s indicators

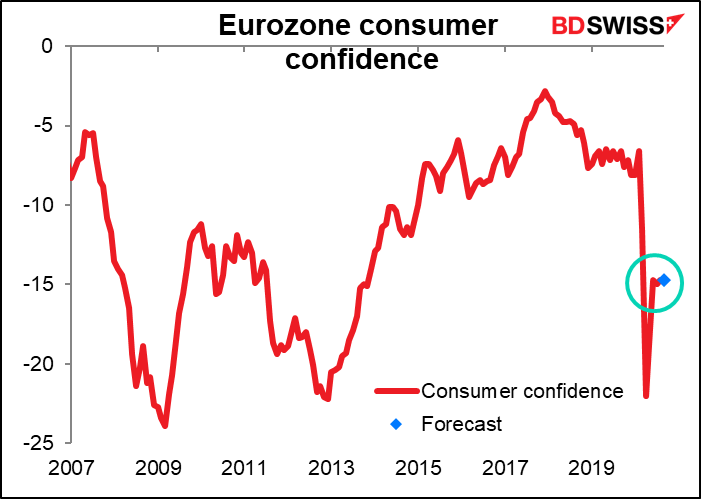

EU consumer confidence is expected to be unchanged at a not-particularly-wonderful level. I think that’s about par for the course. US consumer confidence has bounced back somewhat from the lows but has been trending sideways without recovering. I think that’s the best we can hope for while the pandemic still rages.

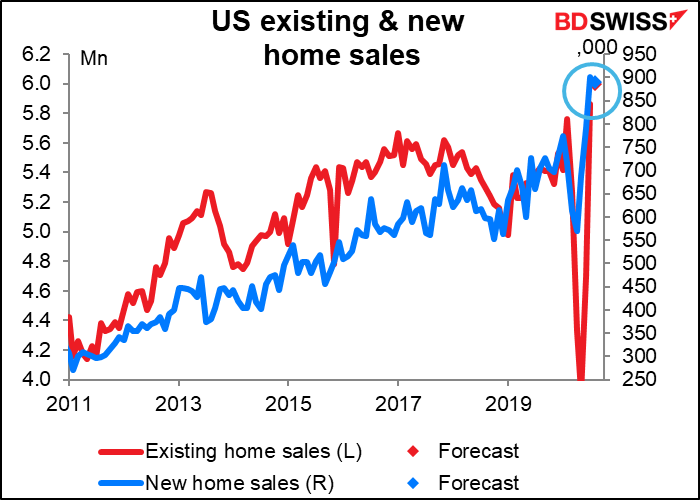

US existing home sales are expected to be up 2.4% mom to 6.0mn units on an annualized pace. Existing home sales surpassed February’s level last month (July) to hit the highest level since the early-2000s US housing boom. Today’s figure is forecast to extend that expansion. New home sales, out Thursday, are forecast to be down 1.2%. Housing sales are caught between the surge in demand that was left over from earlier in the year, when no one could look at houses, and the fires on the West Coast that are disrupting life there now.

FYI I just heard yesterday from a friend who said she and her husband are leaving one of the major cities in the US to move to a less urban (and less expensive) city some 130 miles (200 km) away. “As we are now both able to work remotely and we found an architecturally interesting home in a quiet area, we decided to go for it,” she said. I think this pretty much sums up the decisions of tens of thousands of people around the world, not just in the US.

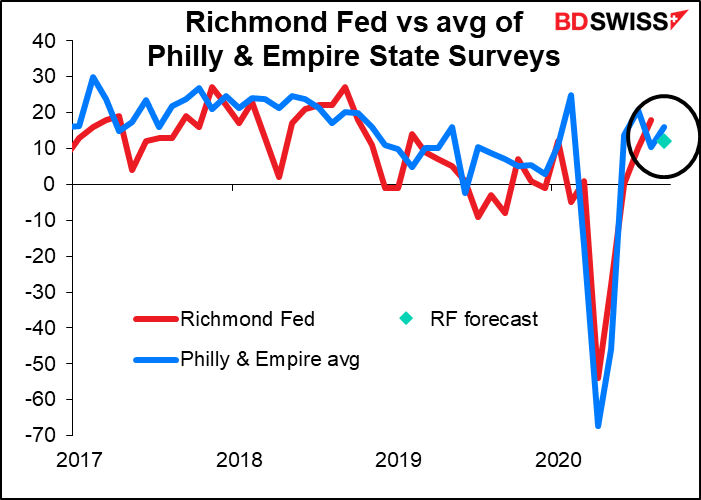

The Richmond Fed manufacturing survey is expected to be down somewhat but still remain well in expansionary territory. This would contrast slightly with the Empire and Philadelphia Fed surveys, which on average rose (thanks to a sharp rise in the Empire State index). Nonetheless as you can see the small drop that’s forecast would still leave the Richmond Fed survey more or less in line with these other two.

While the market puts more weight on the Empire State and Philly Fed indices – probably because they come out earlier – the Richmond Fed survey best predicts the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) purchasing managers’ index (PMI), one of the most important monthly indicators.

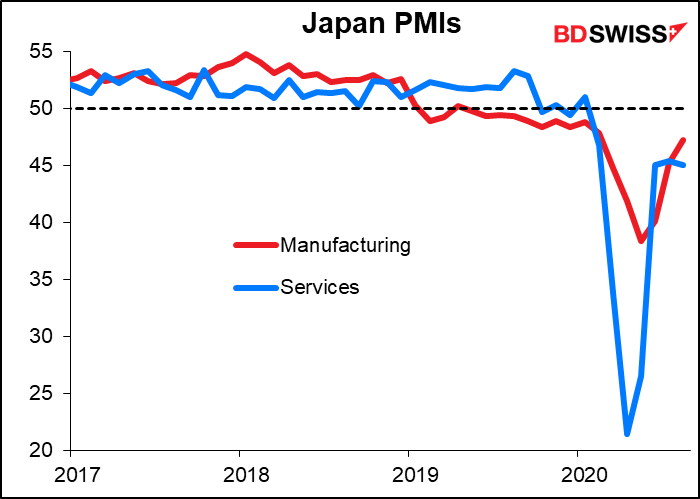

Then overnight we get the first of the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major industrial countries, starting with Japan. Although there are no forecasts for the Japan PMIs, the market does watch them closely (or at least it watches the manufacturing PMI). Alone among the major countries, Japan’s PMIs are both still below the 50 “boom or bust” line that marks the difference between expansion and contraction. My guess is that this stems from the nation’s dependence on trade. With Chinese economic activity picking up (China is Japan’s largest trading partner, accounting for 23% of both exports and imports) perhaps Japan’s PMIs will finally recover into expansionary territory.

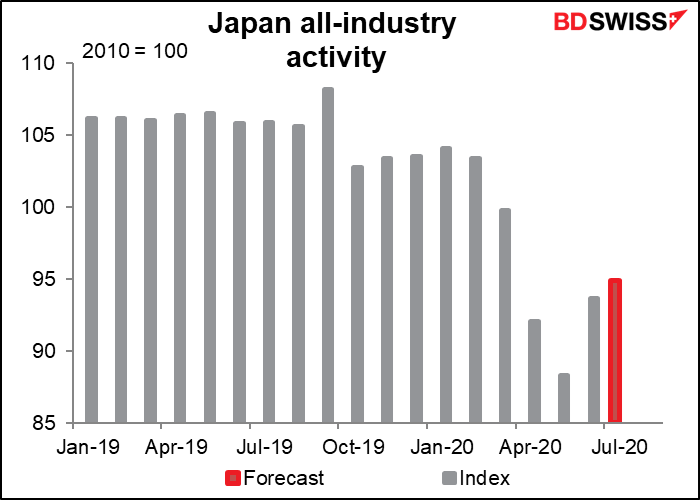

But maybe not. The Japan all-industry activity index is expected to show just a modest rise of 1.3% mom, which would leave it still 8.5% below the pre-pandemic level. Admittedly, this is still expanding, i.e. activity is no longer contracting. Nonetheless it probably wouldn’t be enough to push the PMIs up and over the line.