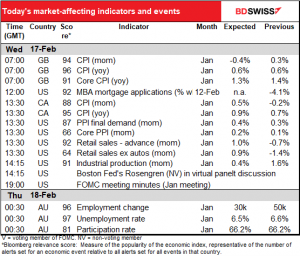

Note: The table above is updated before publication with the latest consensus forecasts. However, the text & charts are prepared ahead of time. Therefore there can be discrepancies between the forecasts given in the table above and in the text & charts.

Rates as of 05:00 GMT

Market Recap

Today’s comment will be somewhat abbreviated as I have an appointment this morning.

Stock markets took a breather yesterday, with the S&P 500 effectively unchanged and the NASDAQ down 0.3%. This follows a down day across Europe. This morning, Asian markets are mixed, with greater China up but other markets mostly down.

The culprit? Too much good news, apparently. Just to review:

● The US House of Representatives has finished its markups (The process by which congressional committees and subcommittees debate, amend, and rewrite proposed legislation) on the COVID relief package. A vote is scheduled for Feb. 26th.

● The US has extended the CARES Act mortgage forbearance, which allows people hit by the pandemic to stop paying their mortgages without losing their homes, and foreclosure protection. This will prevent millions of people from becoming homeless.

● Vaccine rollout continues worldwide; meanwhile, the number of new cases have declined notably.

● Lots of better-than-expected data recently: GDB beats in Japan, Thailand and Singapore on Monday, ZEW survey expectations index soaring instead of falling as expected (71.2 up

from 61.8 vs 59.5 expected), and Empire State manufacturing index also beating expectations (12.1 up from 3.5, vs 6.0 expected).

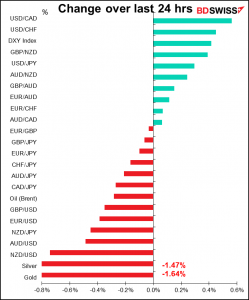

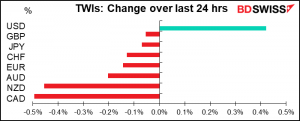

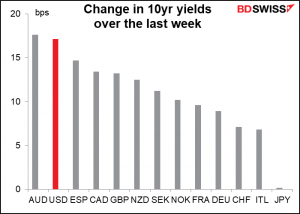

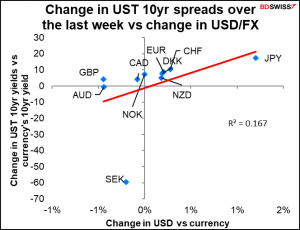

Once again, as I mentioned yesterday, this is causing bond yields globally to rise and yield curves to steepen, only yesterday it happened so much more in the US than it did elsewhere that it caused the dollar to appreciate.

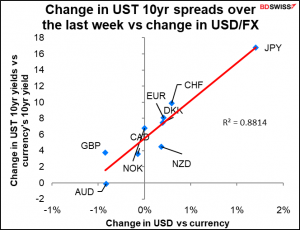

You can see that with the exception of SEK, the relationship holds pretty well: the dollar gained the most vs countries where the spread of US Treasuries over that country’s 10-year yields also rose.

Without SEK:

Today’s market

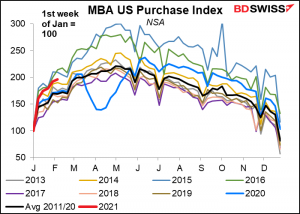

Mortgage Bankers’ Association (MBA) mortgage applications have been holding up well so far as the housing market remains one of the bright spots of the US – indeed the global – economy (“bright” for those who own houses, that is, not for those trying to buy one).

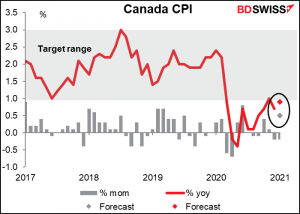

Canadian inflation is forecast to accelerate a bit, as has inflation in many other countries recently – the rise in oil prices plus the reweighting of CPI baskets to take into account changes in spending patterns has had that effect in many countries. I don’t think it’s significant though as a) central banks expect it and therefore will “look through” the changes, and b) they’re not concerned about reining in inflation anyway – on the contrary, they’re trying to create inflation. So a higher inflation rate won’t necessarily get them to change policy, at least not any time soon.

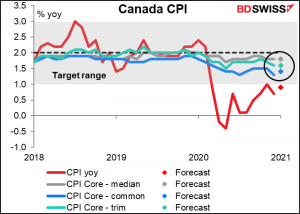

In Canada’s case, there’s something else to consider too. The Bank of Canada doesn’t use the headline inflation measure as its preferred inflation gauge – it uses three core measures of inflation as operational guidelines: CPI-common, which tracks common price changes across categories in the CPI basket; CPI-trim, which excludes upside and downside outliers; and CPI-median, which tracks the median inflation rate across CPI components. Right now all three of them are well within the Bank of Canada’s target range and two aren’t expected to change this month. If we just went by inflation, the Bank of Canada wouldn’t have to do anything out of the ordinary right now, since it’s achieving its inflation target.

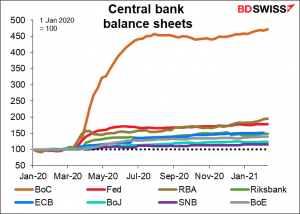

But on the contrary, the Bank of Canada has been the most aggressive of the major central banks in expanding its balance sheet since the pandemic hit. So clearly it’s not only inflation that these guys are worried about.

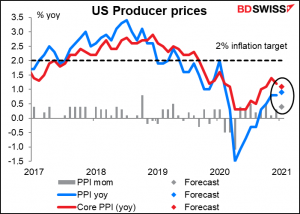

The US producer price index (PPI) is probably of more interest to the stock market than to the FX market, although it could have some impact on USD if it affects the bond market.

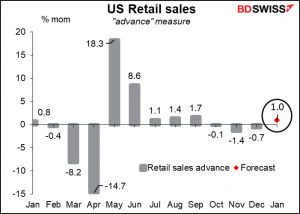

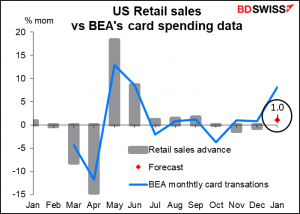

US retail sales on the other hand are one of the big indicators every month. This month’s figure is expected to show a mon increase, the first in four months, thanks to healthy auto sales plus the latest round of economic relief checks ($600), which began to hit consumers’ accounts during the month. The expected rise in retail sales shows the power of fiscal policy to dig the economy out of its hole.

There could well be an upside surprise, IMHO. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) compiles monthly data on spending through payment cards – credit cards, debit cards, and gift cards. Their data showed a strong 8.1% increase in spending in January.

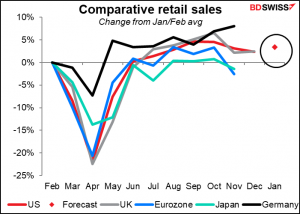

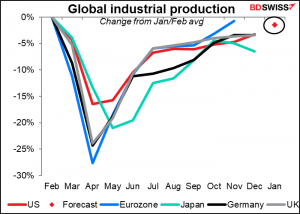

The US spending recovery has been pretty much par for the course – below Germany, above Japan, in line with the UK.

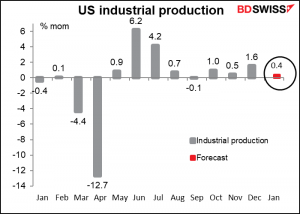

US industrial production is expected to show a slowdown in the rate of growth. This could be taken as a negative for the US economy.

Here too the US is in the middle of the pack internationally.

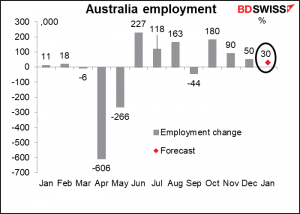

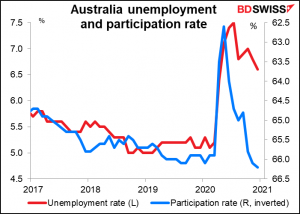

Finally, overnight we get the Australian labor force survey. This is probably the key indicator for Australia nowadays, as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) said as recently as December that “the Board views addressing the high rate of unemployment as an important national priority,” although admittedly they dropped that line in their latest statement. On the contrary, they said “there has been strong growth in employment and a welcome decline in the unemployment rate to 6.6%.” Nonetheless they also noted that it “remains higher than it has been for the past 2 decades and while it is expected to decline, the central scenario is for unemployment to be around 6 per cent at the end of this year and 5½ per cent at the end of 2022.” This compares with their pre-pandemic target of around 4 ¾% for the unemployment rate. In other words, they still have a long way to go before they can start normalizing policy. The big risk for Australia’s unemployment is when the JobKeeper Payment scheme, a subsidy that helps companies affected by the virus keep their employees on the payroll, expires at the end of March. However, given the recent strength in new job creation, the country may be able to avoid a sharp fall-off in jobs when the program ends.