There are two central bank meetings on the schedule for next week, and both of them have possibilities for a change in their bias, although policy is likely to remain unchanged at both. There’s also the monthly US nonfarm payrolls on Friday. But overall, I think the main focus of attention will continue to be the revolution in the stock market as retail investors continue to storm the castles of the financial elite.

Meanwhile, the debate in Washington about the new administration’s fiscal plan continues. It remains to be seen how much of their $1.9tn plan they can push through the evenly divided Senate. The more they get, the better the markets will like it.

Australia: RBA meeting may only be the opening act

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) meets on Tuesday, but that may be just the warm-up act for the main event: Gov. Lowe’s speech on Wednesday. Gov. Lowe speaks on the “Year Ahead” Wednesday and Friday will testify before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics shortly before the RBA releases its quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy.

Lowe made speeches with the same title at this time in both 2019 and 2020. Last year (Feb. 5) was an outlier of course but the Feb. 6 2019 “Year Ahead” speech was substantially more dovish than the post-meeting statement that the RBA had released only a day before. He’s likely to use this year’s speech as well to set out a road map for policy that could be more important than the meeting the day before.

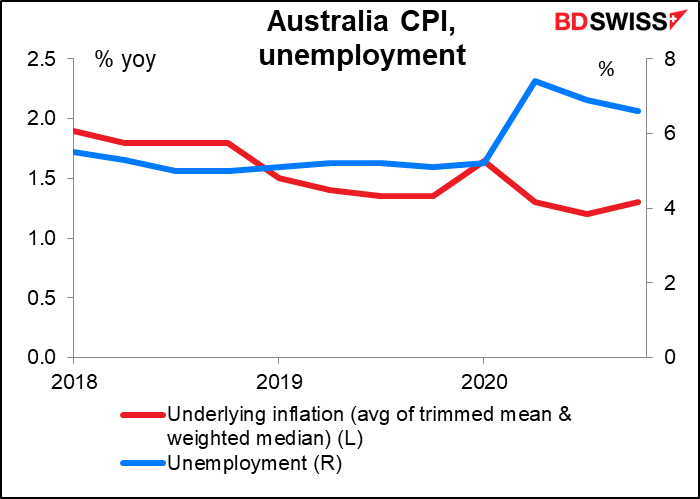

I expect the RBA to keep all its policy settings on hold, but for the post-meeting statement to upgrade the near-term forecasts, the details of which will be includes with the Statement on Monetary Policy on Friday. The recent good data on employment and inflation suggest that the optimistic scenario outlined in the November Statement is more like a central case.

The questions Lowe is likely to address include, what’s next for the RBA’s quantitative easing (QE) program when the current AUD 100bn program expires at the end of April. Will they extend it or “taper” it or simply let it end? Also, what will they do with their Term Funding Facility (TFF) when it expires at the end of June? They may decide to narrow the focus more specifically on business lending. And what about their yield curve control (YCC) policy, which is aimed at keeping the benchmark three-year bond yield at 0.10%? They may decide to continue it, but for how long? And will it continue at that near-zero rate? They’ve said they don’t expect to increase the cash rate for at least three years, but not the three-year bond yield.

Gov. Lowe may announce on Wednesday a substantially more optimistic growth and employment outlook than the RBA had back in November and therefore a less dovish stance towards monetary policy. That could be positive for AUD.

Bank of England: a tilt to the dovish side

The Bank of England is not likely to change policy at this point, but it could hint at a possible further easing of policy in the future – which would probably be enough to send the pound lower.

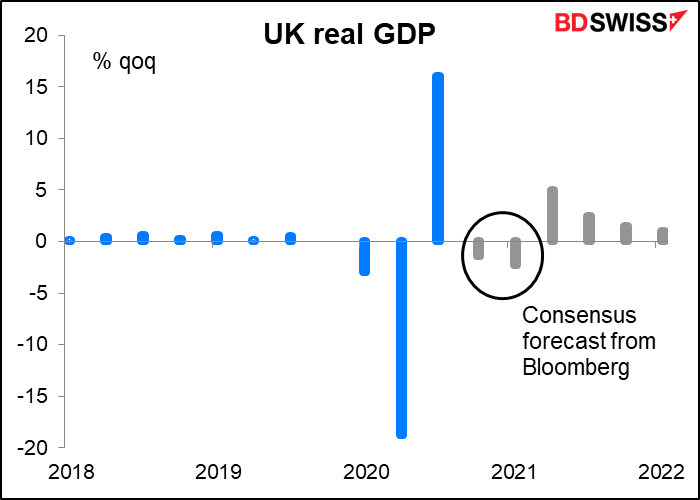

The UK economy is doing better than the Bank expected, but that’s relative to their dismal projections in November. They were expecting GDP to fall by 2% qoq in Q4, but the market “only” expects a 1.4% fall – great stuff!

The BoE meeting will include an update of their forecasts in the quarterly Monetary Policy Review.

Note though that the market’s expectations are for Q1 to show a drop in output as well, meaning that technically the UK is in recession (two consecutive quarters of contraction). In contrast, the Bank forecast in November that the economy would grow 2.4% qoq in Q1. Given that disappointing start, it’ll be difficult (that’s a euphemism for virtually impossible) for the UK to hit the Bank’s forecast of +7.25% growth in 2021.

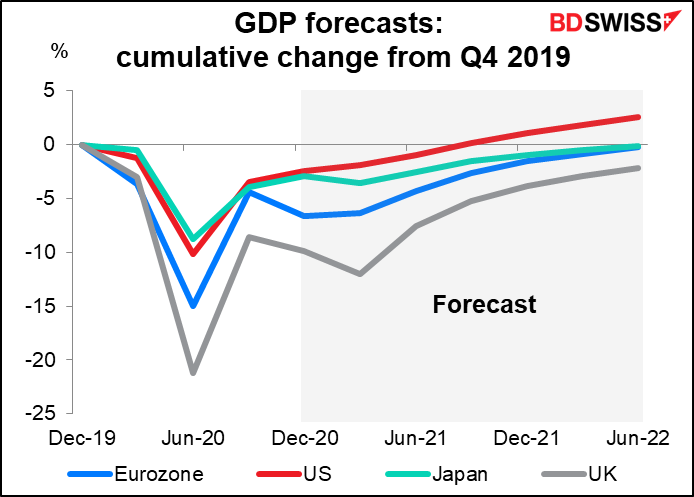

That suggests the UK may be in a singularly poor position internationally.

And we’re only beginning to fathom the problems that Brexit has caused for the economy. The horror stories about trucks refusing to carry goods from the Continent to Britain, of companies having to raise prices for goods imported from China (because they first go a warehouse in the EU for distribution), of not enough pallets that meet regulations, etc etc… But the BoE has already assumed such disruption in its scenarios.

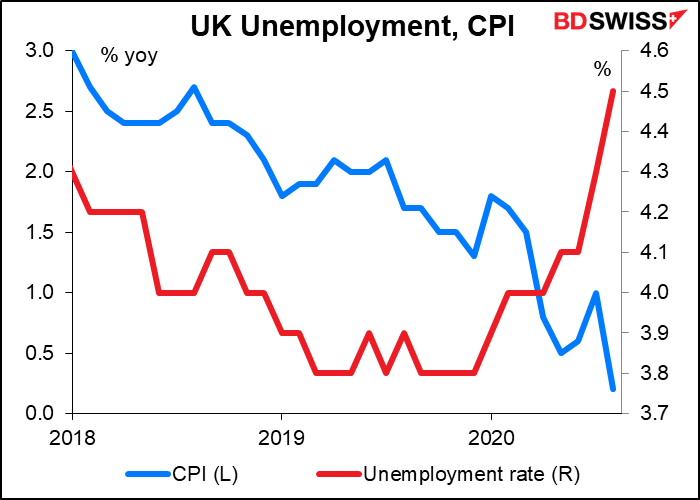

Meanwhile, unemployment is rising while the country heads for deflation. Note though that although bad, this too is better than the Bank’s dismal projections – they had expected the unemployment rate to hit 5.8% in November and 6.3% in December, whereas it was “only” 5.0% in November – so much winning! That’s not due to anything great about the economy though, but rather companies taking advantage of the government’s expanded furlough program, which implies that they’ll have to keep buying bonds in order to finance this “improvement.”

What’s the Bank’s likely reaction going to be? I don’t think they will make any changes in their policy at this point, although I wouldn’t rule it out entirely. I think they are at least likely to come out with a relatively dovish statement. In particular, they could formally include negative rates in their possible policy tools. For example, in their December statement they said “If the outlook for inflation weakens, the Committee stands ready to take whatever additional action is necessary to achieve its remit.” They could be more specific than that this time, adding “including cutting rates below the zero bound,” or something like that. The likely downgrade of the outlook in the new Monetary Policy Review would be sufficient explanation. Otherwise, I expect another unanimous vote to keep rates and the pace of asset purchases unchanged for now.

But given the damage that the virus and lockdown have inflicted on the economy recently, I think the risk is that they do more than this. A small cut in rates, say to zero, would be entirely possible. My view above – a dovish hold – is probably the market consensus, so a cut in rates would be negative for the pound.

Nonfarm payrolls: expected to be up slightly

After falling in December – the first decline since the huge drop in April – nonfarm payrolls (NFP) are expected to be up slightly this month. The forecast rise of +50k would be the smallest rise since the pandemic started, but at least it would be a rise, as opposed to December’s fall.

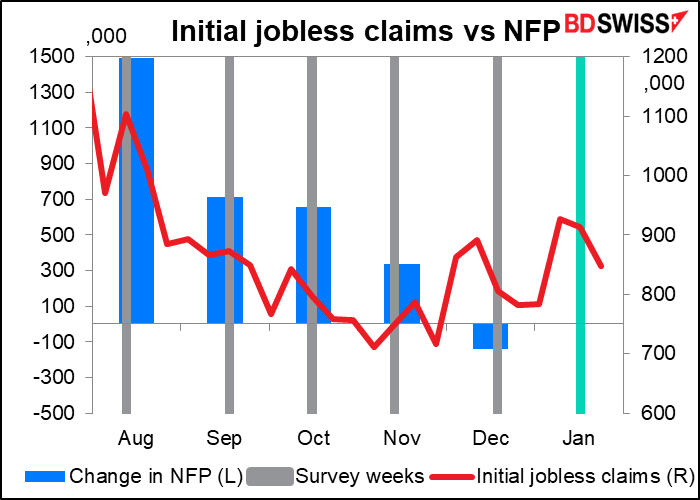

However, I’d say there’s a good chance that the figure misses expectations and falls once again. The weekly jobless claims were 13% higher during the January survey week than the December survey week. This could cause some problems.

The unemployment rate is expected to remain at 6.7% for the third month in a row. Progress in the labor market has stalled. This is bound to worry the Fed, which is clearly more concerned with the labor market nowadays than with inflation. For example, next week the Atlanta Fed is hosting a four-day seminar on Uneven Outcomes in the Labor Market: Understanding Trends and Identifying Solutions. I haven’t seen any of the regional Feds host even a one-day seminar on inflation recently (but I could’ve missed it). It’s also likely to worry the new folks at the Treasury. Treasury Secretary Yellen focused on the labor market when she was Fed Chair, as befits someone whose academic career was as a labor economist. Her PhD thesis was titled, ““Employment, Output and Capital Accumulation in an Open Economy: A Disequilibrium Approach.” A stalled labor market should therefore be of great concern to both the monetary and fiscal authorities in the US.

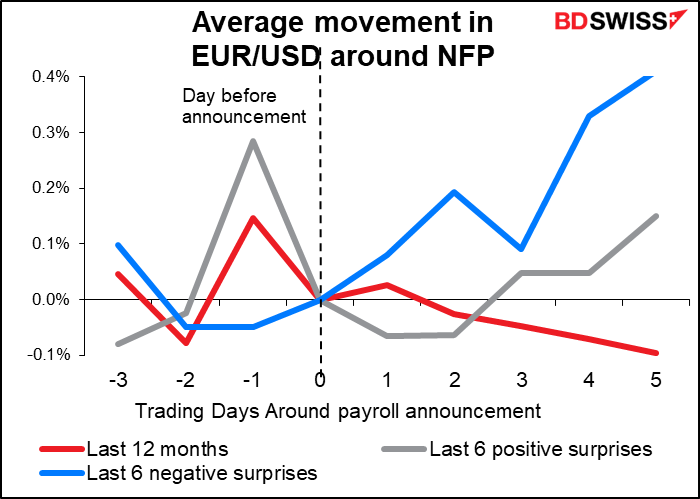

What impact is this likely to have on the currency? Recently, EUR/USD has tended to rise (i.e., the dollar has tended to weaken) regardless of whether the NFP has beaten or missed expectations. It’s just weakened more when there was a negative surprise than when there was a positive surprise. (Note: the “last 12 months” line doesn’t necessarily follow the other two, because they cover two different periods.)

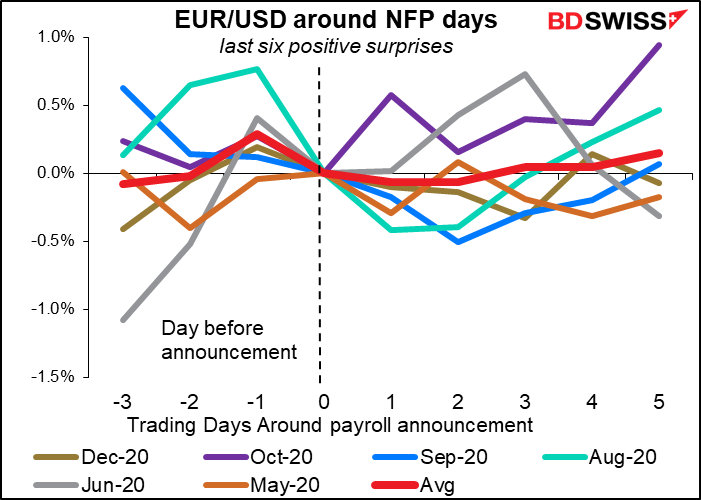

You can see that a positive surprise hasn’t always helped the dollar to rally vs EUR, especially last October (purple line).

On the other hand the dollar has generally weakened on a negative surprise, although November was an exception (gold line).

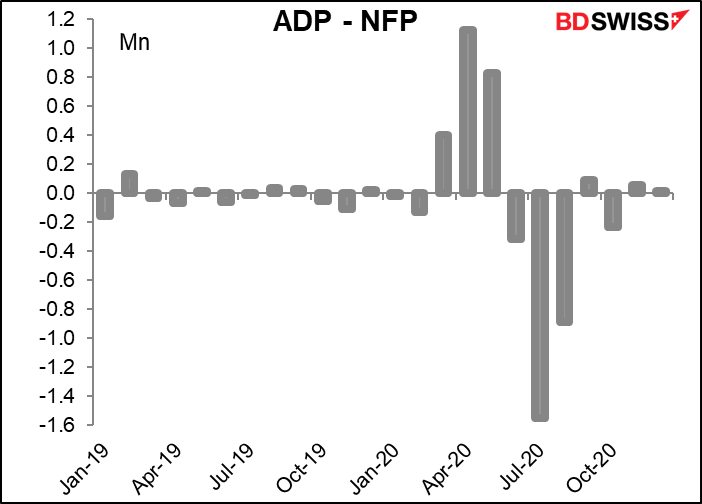

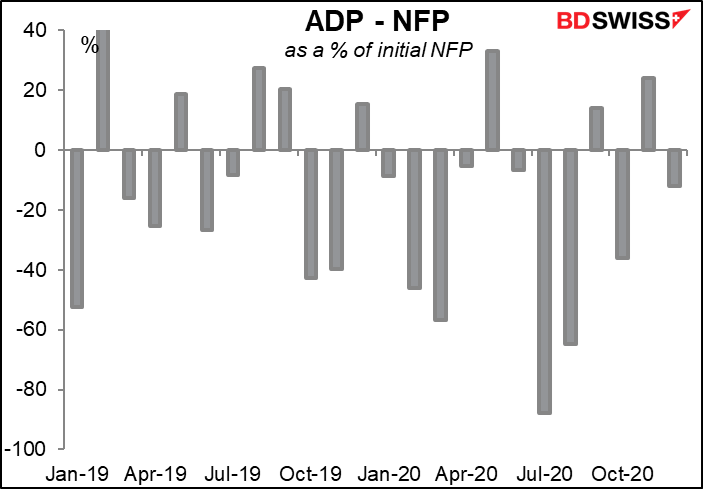

Of course the NFP will be preceded by the Automated Data Processing (ADP) report on Wednesday, which will be watched closely as an (imperfect) indicator of what the NFP might be. The figures have gotten closer recently…

…but that’s probably just because the figures have gotten smaller. Looked at as a percent of the NFP figure, you’d be hard-pressed to tell any difference between now and two years ago.

Other major indicators

The other major indicators out during the week are the final purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for those countries that announce initial ones and the one-and-onlies for the others. The manufacturing PMIS are out on Monday and the service-sector PMIs on Wednesday. As usual, the closely watched US Institute of Supply Management (ISM) version of these will come out 15 minutes after the final Markit version is released.

China’s official PMIs come out on Sunday, while the Caixin/Markit versions come out with the other Markit PMIs.

Eurozone GDP comes out on Tuesday, but by that time we’ll have had Germany, France, and Spain from today, which account for 60% of Eurozone GDP. As the graph shows, those three alone are pretty much all you need to get a good idea of overall Eurozone GDP (98% correlation). The result therefore shouldn’t come as much of a shock.

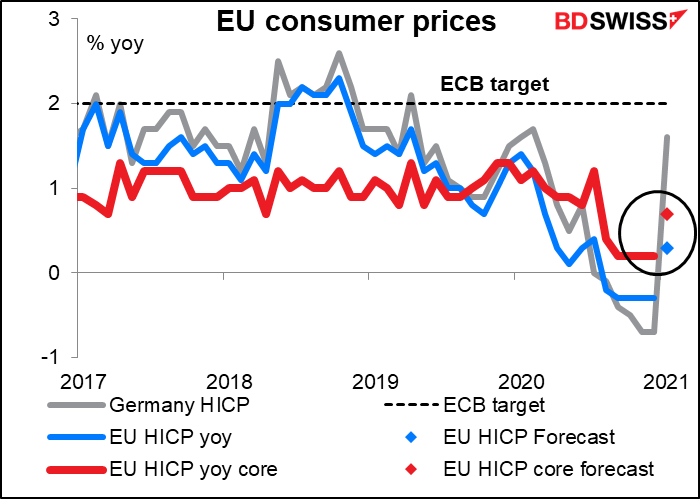

We also get the Eurozone consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday. The German CPI, which came out yesterday, was expected to rise, thanks to various factors such as the end of a temporary VAT reduction, higher energy prices and the rebalancing of the CPI basket, but the figure was shockingly higher nonetheless — +1.6% yoy vs +0.5% expected (-0.7% previously). Those factors were unique to Germany though and aren’t expected to push the EU-wide CPI up as much.

Canada as usual announces its employment data out at the same time as the US. No forecast is yet available, but a weak figure probably wouldn’t surprise the Bank of Canada. After their recent meeting, they said, “Canada’s economy had strong momentum through to late 2020, but the resurgence of cases and the reintroduction of lockdown measures are a serious setback. Growth in the first quarter of 2021 is now expected to be negative.” So a fall in employment probably wouldn’t force any rethinking of policy.