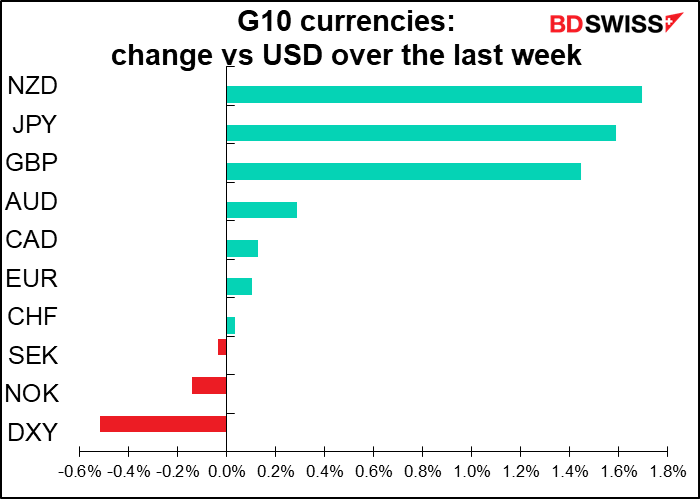

Once again the Fed sets the pace, but it’s a hard act to follow. At least two other central banks (European Central Bank & Bank of Canada) are currently undergoing similar reviews of their methods of operation, but can or will any others follow the Fed’s path to “average inflation targeting”? This week’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting highlighted the fatal flaw in the Fed’s new strategy: it describes how the Fed will act when inflation starts rising but doesn’t say anything about persistent under-target inflation. That’s the problem that almost everyone is facing nowadays, and that’s the problem that no one has come up with a solution to.

Despite what Fed Chair Powell said, the Committee members don’t seem to be convinced that they’ve found the answer yet either. At the press conference, one observant reporter pointed out to Powell that the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) gives the Committee’s median forecast of inflation (both headline and core) for 2023 as 2.0%, yet the Fed has pledged to keep rates unchanged until inflation is above 2.0%. “So are you confident?” the reporter asked. “Is this just the committee is not confident that not only can it not hit its 2% goal, but now it can’t hit its goal of being above 2%?” “Not at all,” Powell replied. “I don’t think there’s any conflict between those two because the way [the forecasts are]set up, their projections don’t show the out years.” In other words, he expects inflation to surpass 2% sometime after 2023.

But the reporter wasn’t buying it. He pressed the point further: “why wouldn’t one of those years at least show inflation being above 2%?” In response, Powell explained, “Because we think looking at everything we know about inflation dynamics in the United States and around the world over recent decades, we expect it will take some time… There’ll be slack in the economy. The economy will be below maximum employment, below full demand…It’s a slow process, but there is a process there…”

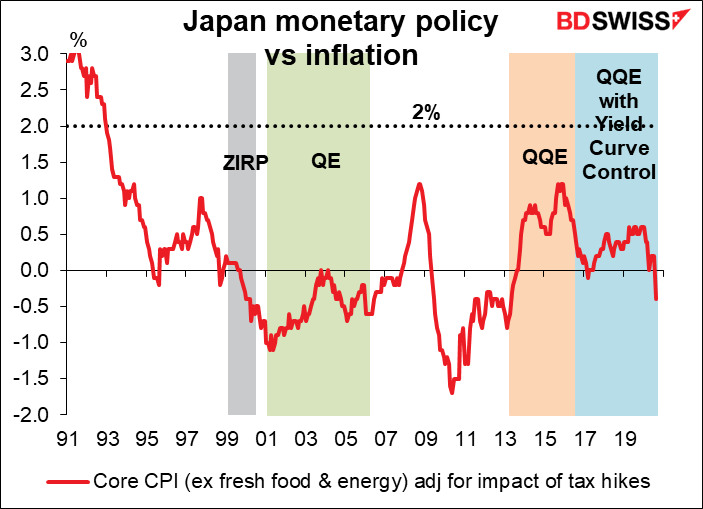

How much time might it take for inflation to get back to over 2%? Well, let’s look at Japan. They’ve not only thrown the book at the problem, they wrote the book on non-conventional monetary policy. And yet, excluding the impact of tax hikes, December 1992 was the last time inflation hit 2%.

In fact, Japan appears to have given up on ever getting inflation back to 2%. In April’s quarterly Outlook Report it slashed its inflation forecast for FY21 to 0.0%-0.7% from 1.2% – 1.6% and forecast still-far-below-target inflation for FY22 (0.4%-1.0%). It lowered that forecast slightly further in July (FY22 +0.5%-+0.8%). And even those forecasts are looking optimistic as Japan fell back into deflation in August, as measured by “core-core” inflation. Moreover, if newly anointed PM Suga gets his way, inflation will probably slow further as mobile phone charges are cut (the 40% reduction in charges that he’s seeking would reduce the yoy rate of inflation by almost 1 percentage point).

But what does Japan do? Nothing. It looks like Japan has given up on trying to get inflation higher. Yet it hasn’t changed its policy either. It continues to operate an ultra-loose monetary policy on the assumption of prolonged below-target inflation. They simply find other reasons to pursue the same policy. “While price stability is of course our first priority, it’s only natural that we also aim to ensure a healthy economy including the state of employment,” Gov. Kuroda said after this week’s BoJ meeting.

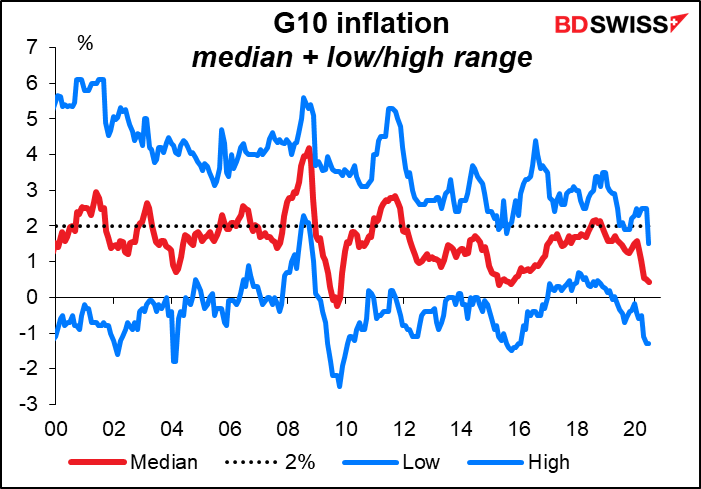

This problem is hardly unique to Japan. Since the Global Financial Crisis some 10 years ago, headline inflation throughout the G10 has barely made it to 2%. Nowadays even the country with the highest inflation in the G10 (Norway) has inflation less than 2% (1.7%).

What this analysis suggests is that many of the people just now entering the financial industry can reasonably expect to retire without ever having seen the fed funds rate go over 1%. I think that should be more negative for the dollar and positive for gold than it was.

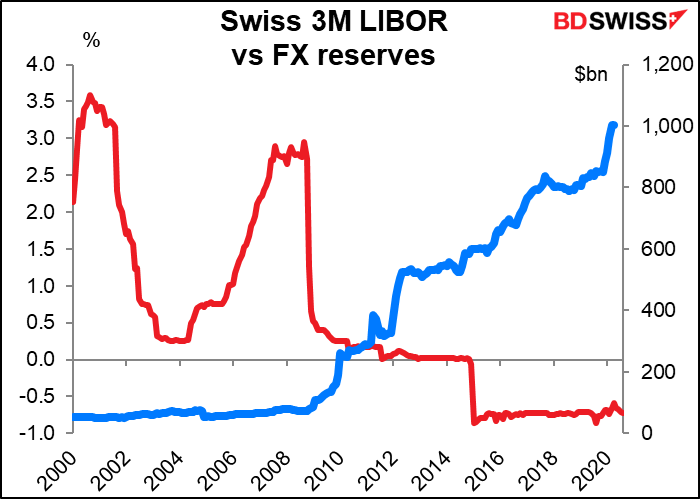

I wonder if gradually all central banks will reach an equilibrium like Japan, where they’ve exhausted the tools of monetary policy, standard or non-standard, and yet inflation remains far below their target levels. In that case, what can they do to support their economies? FX intervention seems to be all that’s left.

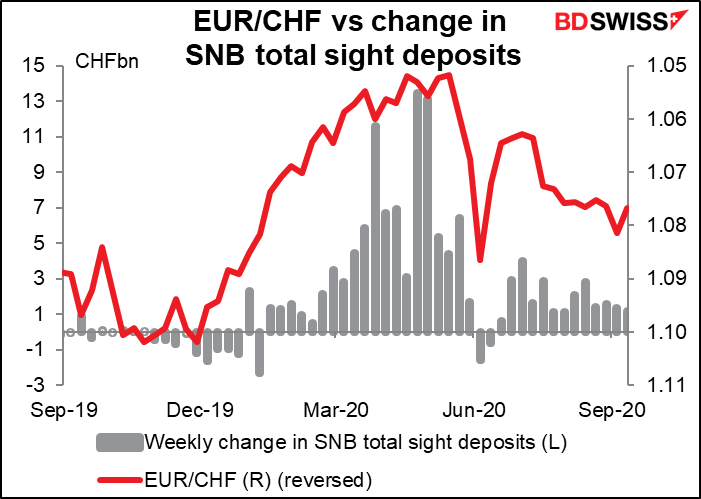

That’s the solution that the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has hit upon. We’ll hear from them on Thursday, but I don’t expect any change in policy there. The SNB hasn’t changed policy since January 2015, when they cut the interest rate on sight deposits from -0.25% to -0.75%, the lowest rate in history. Since then it’s been all FX intervention. (Their intervention started in earnest in June 2009; by Feb 2010 their reserves had doubled from a year earlier, and by May they were up 3x from a year earlier.)

Will the Reserve Bank of New Zealand go down the same path? At their last meeting on 12 August, they kept the Official Cash Rate (OCR) steady at 0.25%, in line with their pledge in March to keep the rate there “for at least 12 months,” and expanded their Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) program by up to NZD 100bn. “Reflecting a possible need for further monetary stimulus, the Committee also agreed that a package of additional monetary instruments must remain in active preparation.” This package, they said, would include a negative OCR, funding retail banks at near-OCR, and the killer: “Purchases of foreign assets also remain an option.” (This wasn’t new; the minutes to the June meeting mentioned this possibility.)

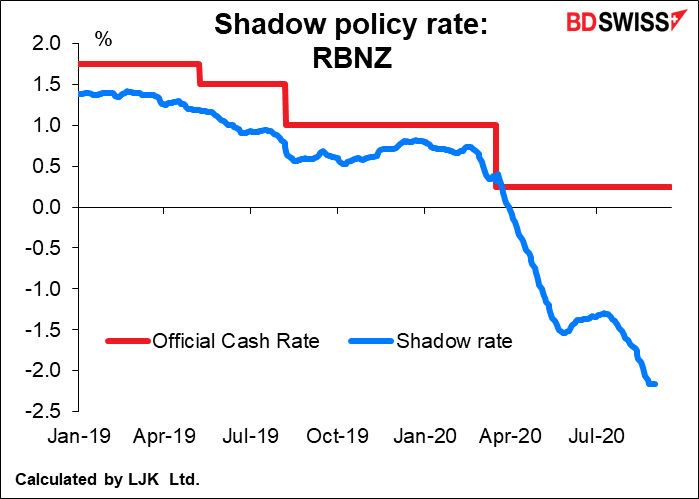

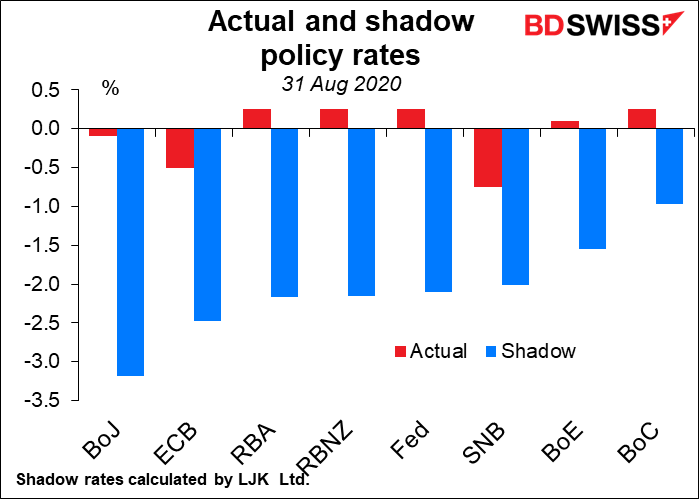

Why would the RBNZ be thinking about such measures? Their policy is already quite accommodative – the effective impact of their quantitative easing is equivalent to a cash rate of -2.16%, according to the “shadow rate” calculations of one of their researchers.

This is quite respectable internationally – not quite where the BoJ and ECB are, but on par with the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Fed, and the SNB.

There was one interesting point at the June RBNZ meeting that may give us a clue. The Monetary Policy Statement said that the “level of monetary stimulus required in the baseline scenario is broadly unchanged relative to the May Statement.” Yet they enlarged the LSAP program anyway. Why, if there’s no need for more stimulus? They explained that it was done “so as to further lower retail interest rates in order to achieve its remit.” In other words, it appears that the LSAP program isn’t feeding through to consumers as quickly or as directly as they had hoped.

The problem, which was much discussed in Japan during the early 2000s, can be summed up by the famous phrase pushing on a string. Just as you can pull on a string effectively but not push on it, monetary policy works very well in one direction – when the central bank wants to cool an overheating economy – but not so well in the other – when you want to revive a stagnant economy. In today’s context, businesses that have no clients or that the government has ordered shut aren’t going to want to borrow money in the first place. So cutting interest rates or subsidizing loans can only do just so much.

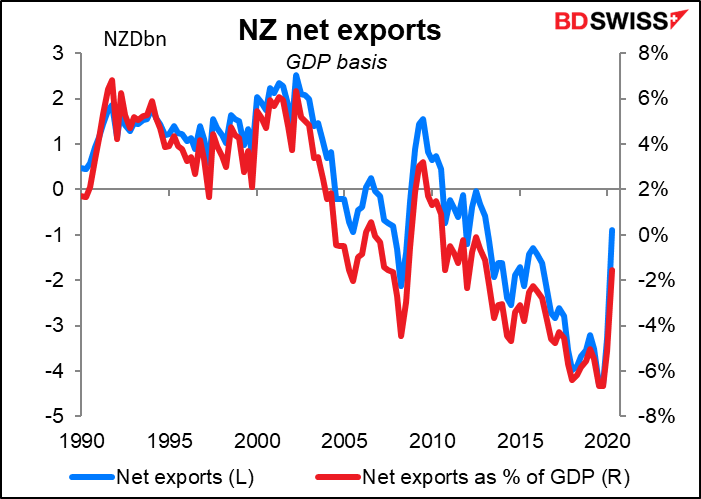

How then can the central bank help nurture the recovery in their country? The SNB and RBNZ have hit upon an idea and I’m afraid the European Central Bank (ECB) is eyeing it too: foreign exchange intervention. A weaker exchange rate would boost exports, which supports employment and overall demand. That’s a more direct way to support an economy than pushing down the price of something that no one wants anyway (that is, the price of borrowing money).

The country’s net imports have narrowed sharply during the pandemic, but they’re likely to reverse course soon as New Zealand is coming out of lockdown earlier than most other countries and therefore consumption patterns are likely to return to normal earlier as well.

I don’t expect the RBNZ to announce an intervention strategy at this meeting. I don’t expect the RBNZ to announce anything notable at this meeting. Back in March they pledged to keep the OCR at its current level “for at least 12 months,” so this is not a difficult call.

Moreover, Finance Minister Grant Robertson Friday cast doubt on whether the RBNZ would need to move to negative rates at all. In an interview with Bloomberg Television, he said the NZ economy is rebounding from recession and looking robust. Noting that things are going well in financial markets and banks are lending, he said the RBNZ “will bear all of that in mind when they come to think about their decisions post-March next year.” Hint, hint.

I think if they do decide next March that further stimulus is needed, their first move would be to lower rates into negative territory. If that didn’t work, they could take a leaf from the SNB’s playbook and combine negative rates with intervention.

The ECB seems to be getting excited about the exchange rate too. Last week, ECB President Lagarde said in the Introductory Statement to the ECB press conference that “the Governing Council will carefully assess incoming information, including developments in the exchange rate, with regard to its implications for the medium-term inflation outlook.” Mentioning the exchange rate in the closely watched Introduction is highly unusual.

Then this week, ECB Executive Board member Fabio Panetta mentioned the exchange rate again when he said “In light of the current outlook for inflation, we need to remain vigilant and carefully assess incoming information, including exchange rate developments.” “Vigilant” is a code word among ECB Board members. Whenever it’s appeared in the Introductory Statement to the ECB press conference, it’s been followed the next month by some change in monetary policy. Of course this wasn’t the Introductory Statement, but the word rang a few bells with the market nevertheless.

I don’t think the ECB would be so reckless as to intervene in the FX market directly to weaken its currency. The SNB and RBNZ can get away with it because they’re tiny countries and have limited bond markets in which to carry out open-market operations (although with $912bn, Switzerland must have one of the highest per capita FX reserves in the world). But loosening monetary policy in order to boost inflation is a generally accepted practice among central banks. The spillover into the foreign exchange market is considered an inevitable externality of domestic monetary policy that’s been acknowledged and accepted internationally (I seem to remember one G7 or G20 meeting following the Global Financial Crisis when the subject came up and it received the green light.)

If the ECB were to start doing this, would Japan be next? I’ve discussed elsewhere how the Ministry of Finance gets excited whenever USD/JPY gets to ¥105. It’s below that now, so we can soon expect to hear how officials are “watching the market closely,” which is the Japanese equivalent of “vigilant.” Weaker inflation caused by say lower mobile phone charges won’t get the BoJ to ease policy further, because no amount of quantitative easing will do anything to push phone charges up again, but weaker inflation caused by an appreciating yen could get the BoJ to move.

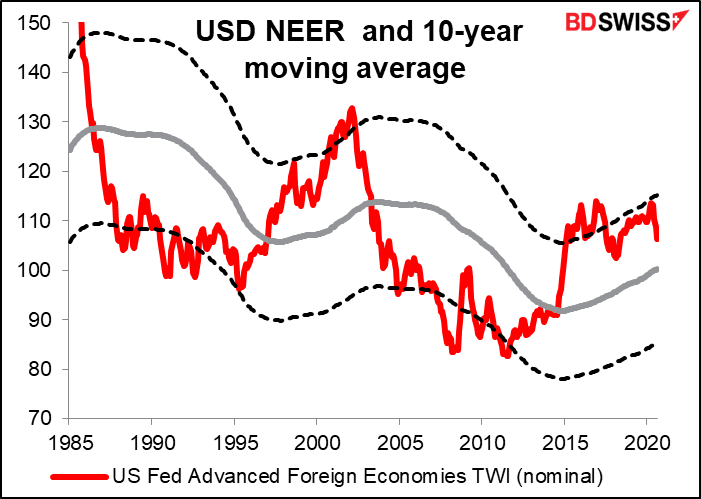

Unfortunately for many countries, the dollar has appreciated to the point where historically it becomes uneconomic and starts to depreciate. We may be in for a long-term decline in the US currency. In that case, many countries will be faced with this same decision. They can’t all depreciate their way out of it. We may be in for a period of currency wars and dueling depreciations.

Next week’s indicators: preliminary PMIs, US durable goods

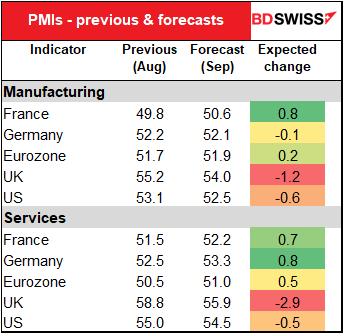

Aside from those two central bank meetings, the main focus next week is going to be the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) from the major industrial countries on Wednesday.

Looking at the forecasts, three things stand out: 1) the manufacturing PMIs are expected to decline (except France); 2) the UK and US service-sector PMIs are expected to decline, too; and 3) the Eurozone service-sector PMIs are expected to gain only slightly.

We can dismiss the expected fall in the UK and US service-sector PMIs as a function of the fact that they’re relatively high to begin with. The UK service-sector PMI for example was the highest it’s been since April 2015. A decline would still leave both comfortably in expansionary territory.

The expected fall in the manufacturing PMIs and the forecast tepid rise in the Eurozone service-sector PMI, which is barely north of the 50 “boom or bust line anyway, are more worrisome. They suggest a worrisome stalling in the global recovery. The particular weakness of the Eurozone PMIs could weigh on the euro next week.

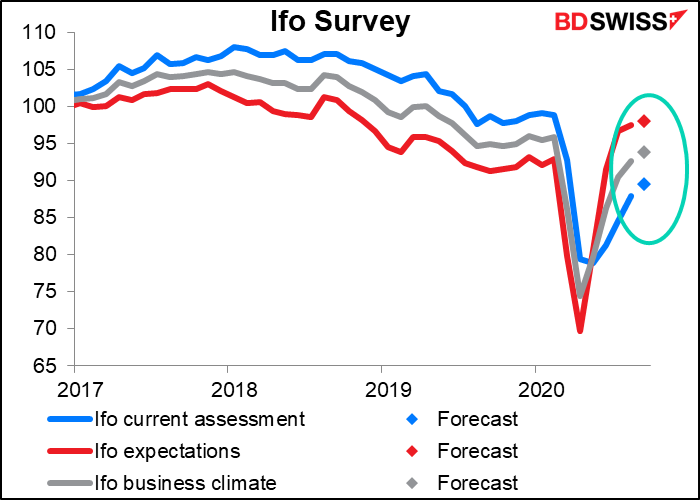

On the other hand, the Ifo survey on Thursday is expected to show continued improvement across the board. That could offset some of the pessimism around the Eurozone, if it does set in.

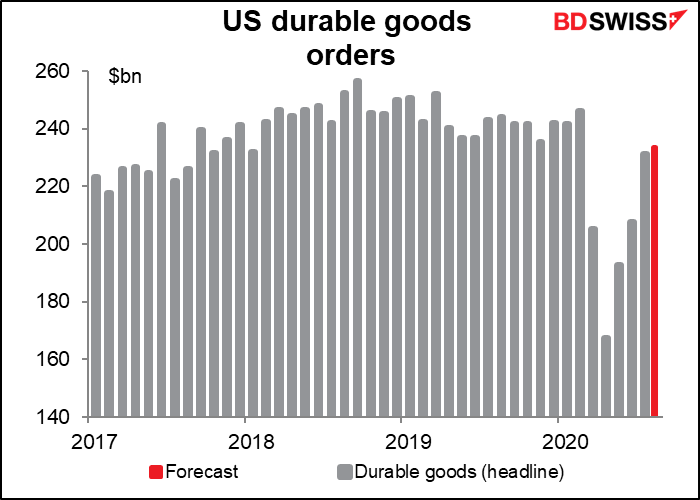

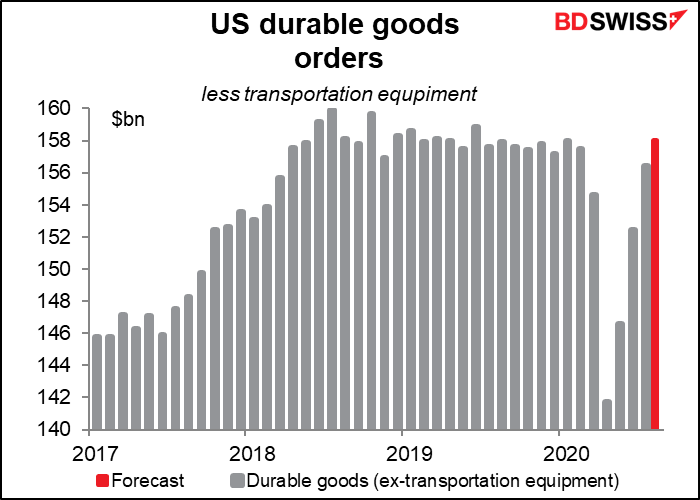

In the US, durable goods orders on Friday are expected to be up 1.0% mom. This would put them still at 4.3% below pre-pandemic levels.

Excluding transportation orders, they’re also expected to be up 1.0% mom -but this would put them slightly above the pre-pandemic level. That could boost USD.

There will be several important speeches Bank of England Gov. Bailey will speak on Tuesday and Thursday. After the Bank took the markets by surprise Thursday and said they would “begin structured engagement on the operational considerations” for implementing negative rates. While the Overnight Index Swap (OIS) market was already discounting negative rates sometime next year, this seems to have come as a big shock to the FX market. We hope Gov. Bailey will clarify the Bank’s intention here.

Also on Thursday, Fed Chair Powell and US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin will appear before the Senate Banking Committee to give their quarterly CARES Act report to Congress. Powell has been quite vocal that the US economy needs more fiscal stimulus. It will be interesting to see how the two fellows compare.

As for Brexit, there are no formal talks scheduled for next week, but I’m sure someone will say something that will get everyone excited.